An Archive Not of Their Own: Fan Fiction & Controversy in China

/As my works have been translated into various languages other than English, I find myself pulled into controversies involving participatory culture and fandom in other parts of the world. For many of the foreign language editions of my books, we create new content by having a scholar who is more deeply embedded in that culture interview me, asking the questions that might most interest readers there.

Textual Poachers is one of my books which has been translated for the Chinese market. I recently received an interview request from a reporter for Sanlian Lifeweek, an important politics and culture publication there, to provide some context for a controversy which is brewing there around real person fiction, which resulted in the shutting down of Chinese access to Archive of Our Own, an important fan fiction platform, which I had recently written about for an Australian publication. You can read more about the events in Chinese fan culture here. In a situation like this, I resist the urge to directly comment on what’s happening in China. I am after all not an expert on Chinese fandom, though I know more about developments there than many Americans because I work with so many Chinese students at USC. So, I framed my comments in regard to the American context, though they were meant to speak implicitly to developments there. I was surprised by the scale of interest in these remarks. The editors shared a snapshot of reader response on social media less than 24 hours after the interview was posted late last week.

Wechat: 80,000 Views, 2291 Shares till now.

Weibo: 2.19 million views, 9442 Shares, 9474 comments, 85,000 likes till now.

All reports are that the article has continued to circulate and gain interest there. The editors asked if I would be willing to share an English language version of the article through my blog and I am happily doing so. This version is expanded slightly from what was circulated in China, containing two questions and responses which were cut there for length.

Controversy & Xiaozhan’s fans

Sanlian Lifeweek

The main controversy surrounding this incident of Xiaozhan’s fans is about RPF (real person fiction) , especially when it involves depictions of restricted category. I noticed that you didn't discuss anything about it in Textual Poachers. Could you please introduce the situation of RPF in the west and your opinion about it?

Henry Jenkins

Real person fiction goes back a long time – much was written by American and British fans about the Beatles in the 1960s. And various forms of grassroots responses to Hollywood stars can be found much earlier. When I wrote Textual Poachers in the early 1990s, Real Person Fiction was relatively rare and still very controversial within fandom. Many of my informants asked me not to write about it and I consented, feeling that it was not my job to expose fandom at a point when it was still working through some of the issues involved.

Over the past few decades, real person fiction has grown as a category of fan fiction and is still more widely accepted by fans and performers, alike. Real person fiction is precisely that – fictions written based on fan fantasies regarding media celebrities (actors, pop stars, sports players, even politicians). Many of these celebrities live in the public eye having little to no private life already in part thanks to the ways they have become drivers of media coverage and their job is in part to stimulate the desires of their audiences. So, we should not hold it against fans that they have erotic fantasies about their favorite performers. When they write this fan fiction, it is a projection of those fantasies into a form which can be shared online with others who share similar desires.

These fantasies are as diverse in their content as the fans who are attracted to a particular performer, and they often involve experimenting with forms of sexuality which may be taboo elsewhere in the culture. American fans often do have some shared norms about what is and is not appropriate to write, mostly having to do with protecting the privacy of other people in the star’s life. Writing about the star is seen as fair game; writing about their family members is not. Some American stars ignore these stories but recognize them as communication amongst fans; a few take great pleasure in them; but fewer and fewer stars are taking offense at the fact people are writing and reading such fictions.

Sanlian Lifeweek

Another contention is that this fan fiction portrays Xiaozhan as a “transgender”. In fact, non-heterosexual content in fanworks is often controversial, How do you understand gender in fandom?

Henry Jenkins

Think of fan fiction as a space free of the commercial constraints that shape the media industry, where people can engage in collective storytelling drawing upon their shared investments in the raw materials popular culture provides them. Much of what gets written deals with romance and erotics because so much of what the culture industry produces also deals with these themes and because such subject matter is central to what makes us human. In our culture, as in yours, our norms about gender and sexuality are in flux and as people make sense of their own identities and those of people around them, they use stories as a vehicle to think through what it might mean to have a particular orientation or relationship.

We write fan fiction as a form of speculation and exploration. For some people, it may be one of the few spaces in the culture where they can express who they are, what they are feeling, what they are desiring. And for others, it is a place of “what if” where they explore in fantasy things they would not necessarily desire in reality. Imagine you were a fan of pirates: writing a story about a pirate does not mean you want to be a pirate. You might simply be wanting to imagine what it would feel like to be a pirate and the same is true for those who write these stories. But in the process of sharing these stories, fans with different sexual and gender identities can communicate and learn from each other about the changes already underway in the culture around them.

Sanlian Lifeweek

Besides, many people are criticizing the idol for losing his voice in this incident, because he didn't come out to stop his fans or apologize for this result. Do you think the idol should be responsible for the behavior of his fans?

Henry Jenkins

Fans are responsible for their own behavior. A performer may express their preferences regarding any number of things beyond questions of gender and sexuality– perhaps the star is a vegetarian and finds stories where they eat meat disgusting or perhaps they have strong political views and do not want other contradictory beliefs ascribed to them. Many fans will comply to that request out of politeness and respect. But fans also reserve the right to read texts on their own terms and that includes making up stories which are not sanctioned by the producers. Most stories include some disclaimer which is intended to signal that the producers do not necessarily approve of what they write and that these works are intended to be read as a product of the fan’s own imagination. Under these circumstances, I would not hold a performer responsible for his fans’ behaviors but the performer is responsible for their own behavior and fans may respond negatively to performers who over-react to the existence of alternative fantasies and insult or hector their audiences.

What is AO3?

Sanlian Lifeweek

In this incident, AO3 was blocked led to the users to boycott Xiaozhan’s works and commercial endorsement. How to understand this strong reaction from users? What role does AO3 play in fandom?

Henry Jenkins

In the pre-internet era, fan productions were largely underground, traded among people who already knew each other, and limited to a small, insular, homogeneous community. With the rise of the internet, more people have been able to access and participate in the production of fan fiction. There’s been an enormous expansion in the number of source texts fans write about; fans around less known texts can find each other online and communities grow. This process is now more open to fans around the world and fandom has become one site for cultural exchange and understanding. The platforms are the spaces where such exchanges take place. Remove them from the equation and all of the practices of fandom will persist; fandom is good at working around all forms of censorship. But the scope and scale of fandom would diminish and with it, the kinds of social exchanges around stories that are today seen as one of the most valuable aspects of online fandom.

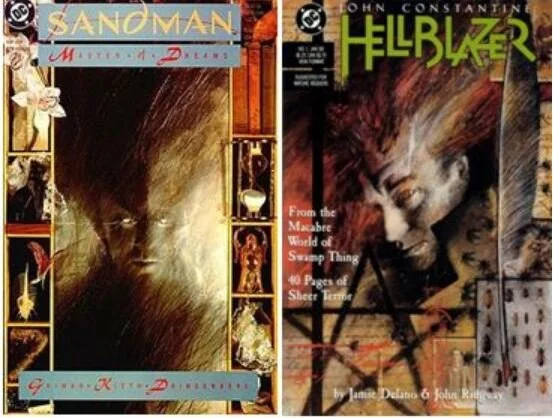

Keep in mind that AO3 is a particular kind of platform. Alongside Wikipedia, AO3 is one of the greatest accomplishments of participatory culture in the digital era. AO3 is not a commercial platform which profits from grassroots expression; the servers are owned and operated by the fan community, where fans deploy their skills in the service of creating a more supportive environment from amateur writers to create and share their stories with each other. Last year, the site was recognized with a Hugo Award, one of the top prizes given for genre fiction, at the World Science Fiction Convention. This award recognizes the accomplishment of AO3 and the Organization of Transformative Works by the top professional writers in American popular fiction. It is understandable that fans in China and elsewhere around the world are horrified at the prospect of closing down access to this site which has been so valuable to so many people who are finding their voices as storytellers for the first time.

Sanlian Lifeweek

However, there is a large amount of pornography, violence and other sensitive content on AO3, many opponents believe that it will have a negative impact on teenagers, who are the important participants of the fandom, and many parents even think that teenagers should not participate in the fan activities. What is your view on this?

Henry Jenkins

I recently wrote a scholarly study of AO3 and the many forms of literacy it helps to foster among its participants, one which built on work by many different educational researchers. Among my findings were that fan fiction sites can be a valuable space for young people to acquire skills (and receive feedback) on their writing from more experienced writers who share these same passions, and it can be especially important as a space for practicing English skills since it often involves cross-cultural communications around shared interests. It has been a space where young people also learn to critically read and reflect on stories, where they acquire coding and other technical skills, where they learn to navigate diverse cultural communities and acquire leadership skills. Work by American educators would describe this as connected learning, recognizing the role which informal, peer cultures play in shaping young people’s access to meaningful educational experiences and resources. Others have written about the distributed mentorship in fandom as people support each other throughout this learning process. I start with this focus on the educational benefits of fandom because the current debate focuses exclusively on risks and not what is lost from denying teens the ability to participate in what are otherwise rewarding experiences for them. The challenge is how to minimize the risks and maximize the benefits.

That said, while teens have participated in fandom, a large part of those on AO3 are adults, engaging in adult conversations on adult topics. Not everything that happens there is appropriate for teen readers and not everything teens write is appropriate for adult readers. Contributors to the site tag and rate their stories deploying a broad range of categories intended to tell the reader about degrees of explicitness, recurring themes and dramatic situations, forms of gender and sexual identity, etc. As a consequence, the site provided far more information that helps readers fan storied they will enjoy and avoid stories that are inappropriate for their needs and desires than most of the institutionalized rating systems within the media industry. While readers bear responsibility for the choices they make from what is offered, they have the potential to make informed choices, knowing what to expect from the stories they choose to read.

How teens acquire knowledge about sexuality is always a vexing question. Adolescents around the world have tremendous curiosity about sexual matters and seek information as best they can. Commercial pornography can be alienating, depicting sex removed from the context of human relations and reduced to body parts and the ways they come together. Fan fiction consistently depicts sex within relationships (in part drawn from the source material), sex involving people the reader cares about, and stories about people working through the complex feelings that sexual relations stirs up in people.

The Formation of Fandom

Sanlian Lifeweek

When you wrote Textual Poachers, the fandom was still far away from public view and could only be active in informal place. This book was part of the process of the fan community to reshape its group identity, speak out to the public, and defend itself to the public. More than 20 years later, in your opinion, what important changes have taken place in the fan community?

Henry Jenkins

The internet pushed fan culture into the public view, ready or not, allowing it to be receptive to a broader and more diverse group of participants. The internet has sped up the process of fan reaction and fan creation so that fan communities may process new content at a speed previously unimagined. It has broken down national borders and cultural boundaries, allowing fandom to be one of the more important crossroads for global digital cultures. It has meant more and more people could create and share stories with each other. This expansion results in heated debates within various fan communities about what kinds of stories are or are not appropriate, a working through of what constitutes acceptable content within a space known for its tolerance for diversity and its openness to new ideas. These debates are now more and more being covered as news and the choices fans are making can and often do have consequences within the creative industries.

Sanlian Lifeweek

Textual Poachers focuses on the "media fan", which is fan of movie and television. In your opinion, what is the difference between media fan and celebrity fan?

Henry Jenkins

Media fans are concerned with popular fictions, often focusing their stories around characters, such as Iron-Man or Harry Potter, though there are thousands of different fan interests, including those around specifically Chinese media content, on AO3. Celebrity fans are concerned with performers, and they may express those interests in many different ways from collecting magazine photographs and sharing gossip online to writing fan fiction. What’s important to recognize is that when fans write about celebrities, they become fictional characters. Fans generally only know things about celebrities which have appeared in some other form of media and anything beyond that is speculation. In most cases, real person fiction is not even speculation about star’s private lives, only the same kind of imaginings of the star’s sexual identity as occurs when fans make up stories about purely fictional characters. There is not a single fandom but rather multiple fandoms which overlap and diverge along many different axis (celebrity vs. fiction being only one) and the same fan may belong to multiple fan communities. These different kinds of fans may sometimes share the same platform, engage in some of the same practices, but this should not confuse us into thinking all fans speak in the same voice.

Sanlian Lifeweek

In Textual Poachers, you talk about an important daily practice for fans is to establish a relationship with a particular piece of text, such as a piece of music, an album, a TV series, and other popular culture texts. Fans love multiple texts, "hunting" in different texts and reconstructing new ones. Text is an important foundation for the formation of fandom. So, in the new media era, has the concept of text changed?

Henry Jenkins

First, I would stress the proliferation of media texts at the current moment. In America, we are talking about the era of “peak television” or “too much good television,” but it is also the era of global television. We have access to a much broader range of media content than ever before and in this context, fans play a constructive role in curating that content, helping some shows get greater visibility. In America, it’s said that one fan brings as many as 20 additional viewers to a television series, and that is one of the many ways that fans generate value for the entertainment industry. Here, fan engagement has become a really important currency within the television industry as Hollywood has come to appreciate the intensity of fan passion, the value of fan publicity, and the importance of satisfying their most valuable consumers. Second, these texts have become more malleable: we can spread them outside their normal commercial circuits; we can offer critical commentary and conduct conversations around them; we can remix them and deploy them as sources of inspiration for our own creative expression; and we can then share those new works with each other online. In such a world, it becomes even more important than before for fans to distinguish between canon (that is, works produced and authorized by media producers) and fanon (ideas and works originating from the fan world). This is one of many reasons where the tags which fans attach to their stories on AO3 are central to understanding the status of these fan works and the ways they are read in relation to the source material they are responding to.

Sanlian Lifeweek:

Therefore, should the fandom formed around "bad text" be criticized? In China, when we criticize so-called traffic stars, we are also criticizing them for not producing “good texts” but still attracting a large number of fans. How to understand this phenomenon?

Henry Jenkins

I can’t say much about traffic stars because I am not a scholar of Chinese fan cultures. But I can speak to your larger question. I would shift the question away from “good” and “bad texts.” Rather, the question should be what are fans finding meaningful about these performers and the texts they generate. I start from the premise that human beings do not engage in meaningless activities. I may not immediately recognize why something is meaningful but my job as a scholar is to understand why cultural materials are meaningful to the people who cherish them. In some cases, cultural materials may strike such awe, may seem so complete in and of themselves, that they inspire little or no fan activity. In some cases, the original works may be promising (holding potentials to say something that matters to their fans) but flawed (failing to achieve those potentials). Here, fans may actively engage in reworking them to more fully develop the elements that speak to them in some powerful way. Fandom is born of a mix of fascination and frustration – if the works did not spark intense interest, they would not generate fandom, but if they fully satisfied fan desires, then they would not need to rework them and recreate them. Finally, I would suggest that in some cases, what is meaningful may not be obvious from the source material: it may have to do with the social relations which the fans forge with each other.

Understanding the Fan Community

Sanlian Lifeweek

Actually, one of the main reasons other groups find it difficult to build a relationship with fandom is because of their unique language. What do you think of that language and the influence it has?

Henry Jenkins

The language fans use grows out of shared interpretations and experiences which have built up over a long history and across multiple texts. Many of the terms were not meant to be broadly understood because they are ways that fans can communicate with each other within a precarious context where companies or governments might shut down their grassroots expression at any moment. Mastering that language allows for a certain sense of belonging which becomes all the more important as the breakdown of traditional civic and family structures leave us feeling more and more isolated and alone. That language reflects the history of fan communities to incorporate and respect people with diverse backgrounds as well as people who feel different from others in their local context.

Fandom, of course, is not the only community which has specialized terms and there’s no reason to expect that the conversations of a subculture should be understood by society at large. Various professional groups – accountants or lawyers, say – have their own specialized languages which allow for efficient communication of regularly recurring concepts, and sports or music fans have specialized knowledge that may seem obscure to people who are not similarly invested. Part of what’s valuable about the internet is that it allows people to find others who share their values and interests, who speak their languages, and to enable conversations amongst them that span both time and geographical space. Fandom is simply one of the most powerful illustrations of what such virtual communities look like

Sanlian Lifeweek

However, we are seeing more and more of this conversation being irrational, which is totally different from the rational position you assume. Cyber violence is everywhere in fandom. Some experts attribute this to the mechanism of new media platforms such as Weibo in China. Do you think this kind of platforms should share the responsibility to help build fandom better?

Henry Jenkins

These issues of cultural divides, flame wars, and yes, cyberviolence do not originate within fandom per se. Scholars, educators, political leaders, policy makers, parents, around the world, are grappling with how to deal with antisocial behavior online in many different contexts. We can certainly point to examples where fan groups took their disagreements too far, including directing massive letter writing campaigns, against producers, performers, critics, and others, to assert their perspective on the choices being made within a divisive cultural context. In many cases in the United States, these angry fans are further stirred up by outside forces, including underground political organizations that want to recruit them for their causes. And these often fringe exchanges get amplified by the news media who do not cover all of the many ways where fans are constructively working through these same issues. These issues are larger than fandom, larger than the platforms where they publish, and reflect a global political crisis. Platforms can play a constructive role in responding promptly, rationally, and fairly to complaints calling out hate speech and other antisocial behavior. Often, in the past, they have been slow to remove content which is offensive and hostile to other communities who share use of these platforms, claiming no responsibility over what gets posted on their sites, and we want to push especially the large scale commercial platforms to have more accountability for the consequences of their choices.

About the Fan Economy

Sanlian Lifeweek

In fact, the fan community is increasingly valued and harnessed. This has created fan economy. However, we can see that on the one hand, fans have an increasingly power in it. For instance, the film industry will choose stars with a large number of fans rather than actors with really good acting skills to participate in different movies. On the other hand, fans are providing more and more free labor. How do we define the identity of fans in this new economy?

Henry Jenkins

The idea that producers chose stars because they will draw larger audiences is not a new idea in the entertainment industry and is not a product of online fandom, even if such spaces increase the visibility and intensity of fan responses to these performers. Films, television, popular music are commercial artforms: certainly we can apply aesthetic criteria to think about what constitutes a “really good actor” but we should also look at how effective this performers is at engaging an audience, at stiring up their interest around a particular story. That is to say, commercial art is judged by a mix of commercial and artistic criteria.

In terms of the role of fans in this new economy, it has indeed taken on greater significance. Fans have taken seriously their roles as publicists, helping to direct attention around their own agenda, and the industries in turn are not only valuing these fans because they play important roles in a media-saturated culture; they also are seeking to control and exploit the energies of fans towards their own ends. The later often comes at the expense of fan control over their own conversations and at the expense of the grassroots creativity we are discussing here. Fans are thus part inside and part outside the media industries today. As I predicted many years ago, the core debates of our time center around the terms of our participation – who gets to participate in what ways under what constraints.