British Comics Go to the Movies (Part 2 of 3) by James Chapman

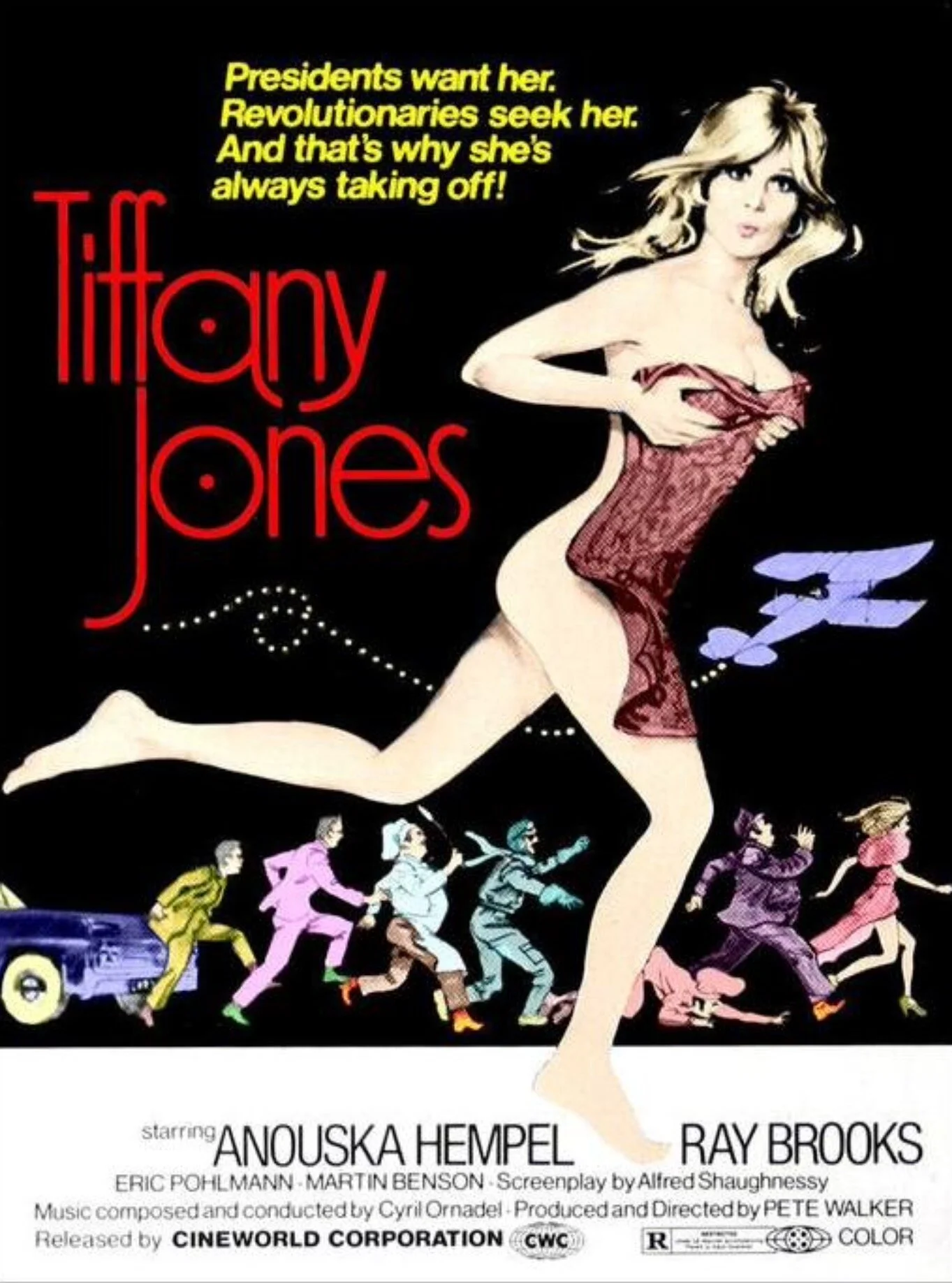

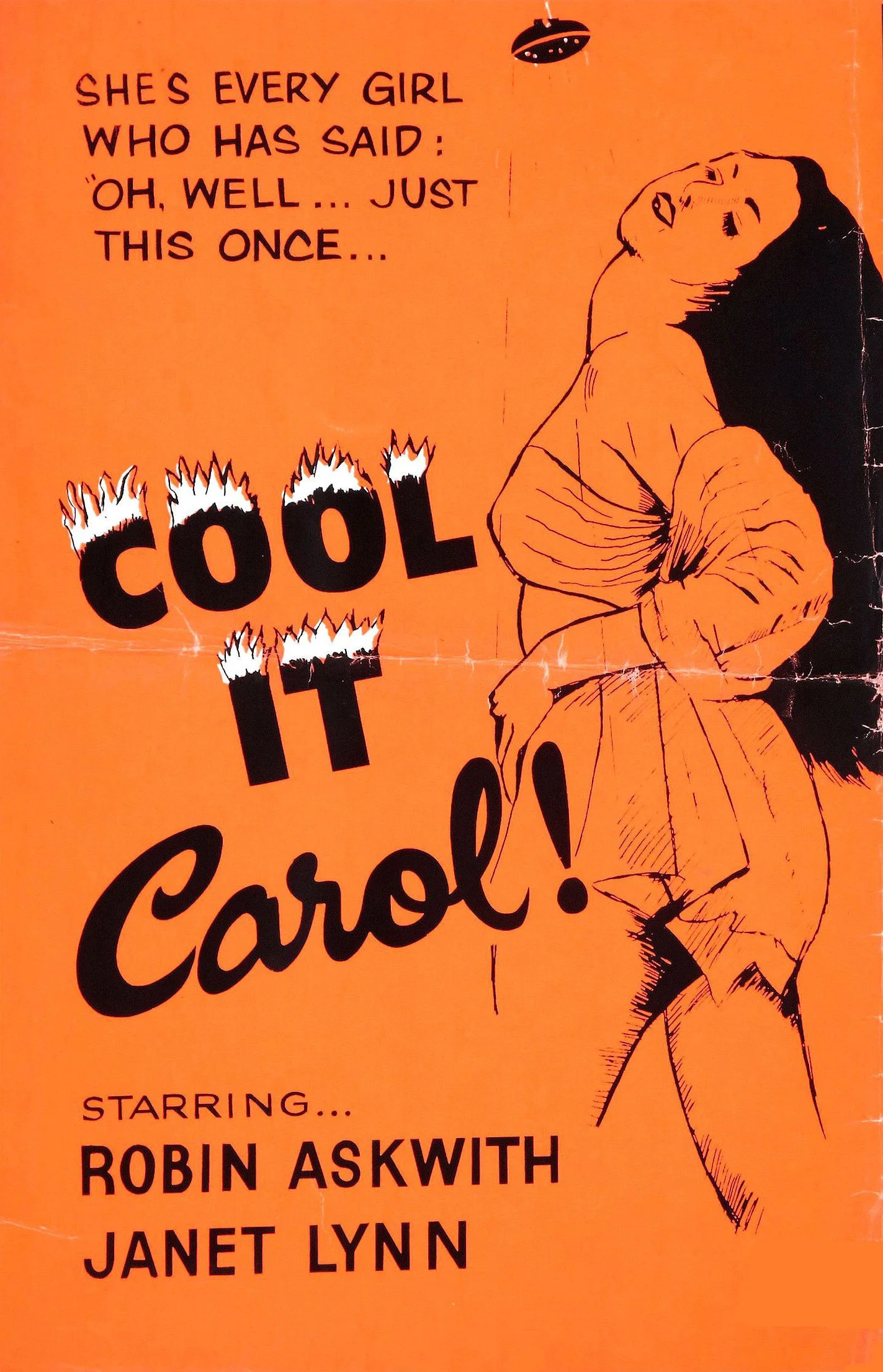

/Tiffany Jones (1972) - produced and directed by British exploitation film-maker Pete Walker – was a sort of Jane for the seventies. Tiffany, who first appeared in a newspaper strip in the Daily Sketch, is a fashion model who, like Jane, tended to lose her clothes at the faintest narrative contrivance. The relaxation of censorship in the 1970s meant that, unlike The Adventures of Jane, Tiffany Jones was able to present its heroine in her natural state, though erotic it isn’t, even in the form of the New Zealand-born model-turned-actress Anouska Hempel, who reportedly later wanted to remove this abomination from her CV. Like other British films of the period, Tiffany Jones has the slightly jaded air of a hangover from the 1960s: its fashion model heroine is very much a throwback to the time of ‘Swinging London’ but that cultural moment had passed by the time of the film’s production. Walker was a low-budget director who specialized in exploitation fare including the sex comedies that were ubiquitous in 1970s British cinema (Cool It Carol!, Four Dimensions of Greta) and ‘punishment’ films in which young women fall prey to sinister oppressors (House of Whipcord, Frightmare). Tiffany Jones includes elements from both those genres: Walker’s penchant for punishment narratives surfaces briefly in a bizarre scene where Tiffany is threatened with torture in a restaurant kitchen – leering heavies menace her with hot soup and whip her with strips of spaghetti – while the climax conforms to one of the conventions of the sex comedy as Tiffany’s model girlfriends (describing themselves as the ‘South London Branch of the Model Girls’ Union’) strip naked at a garden party. Observer film critic Philip French thought it was ‘quite one of the most inept, witless, joyless and unerotic movies I’ve ever seen’.

Of course it’s easy to be dismissive about films that have little cultural ambition: these films are bad but there’s been many an American comic-strip movie of equal disrepute. Who today remembers Brooke Shields as Brenda Starr (1987) or Pamela Anderson as Barb Wire (1996)? But it’s a shame that comic-strip characters who represent something interesting about wider social and cultural discourses of femininity should have received such poor treatment in the movies. I’ve long believed that newspaper comic strips offer revealing insights into social mores and values, whereas the films based on them tend towards parody or camp.

It’s easy enough to make a bad movie on a low budget. To make a bad movie on a big budget, however, surely requires a special kind of skill. Witness for the prosecution: Modesty Blaise (1966). This is yet another film based on a female-centred British newspaper comic strip, which is evidently a subject for further research. Modesty Blaise was one of the so-called American ‘runaways’ produced in Britain during the ‘Hollywood, UK’ investment boom of the 1960s: British-made films backed by American studios, in this case Twentieth Century-Fox, which lavished £1.2 million on this dog’s breakfast of a movie. To put that in context, Modesty Blaise had over three times the budget of Dr No, the first James Bond picture, and was nearly twice the cost of Zulu. Modesty Blaise could – and should – have been a hit. Peter O’Donnell’s sassy adventure heroine, drawn initially by Jim O’Donnell for the Evening Standard from 1963, had all the hallmarks of a first-rate thriller in the style of James Bond. The strip itself was fast-moving, globe-trotting, took itself seriously enough not to be parody but was sufficiently aware of its genre conventions to remain on just the right side of camp. So how did it go so wrong?

What they should have done was commission a script from Brian Clemens, writer of some of the best episodes of the stylish British secret agent series The Avengers, bring in one of the Avengers directors such as James Hill or Robert Fuest to direct, and cast either of the Avengers heroines Honor Blackman or Diana Rigg as Modesty. Instead what they did was turn to auteur director Joseph Losey – director of such brilliant dissections of the British class system as The Servant, Accident and The Go-Between but hardly renowned as a film-maker possessed of a ‘light’ touch – and a miscast Italian art house darling Monica Vitti. Losey had no feel for the source material: indeed it’s not even clear whether he ever looked at the strip. The studio also rejected Peter O’Donnell’s script (which he subsequently used as the basis for the first Modesty Blaise novel, which is far superior to the film) in favour of one by Evan Jones that treated the material as camp in the manner of the contemporaneous Batman television series. There is a germ of an idea in Modesty Blaise, a sort of meta-fictional apparatus in which the ‘real’ Modesty performs as the Modesty of the comic strips. But the idea is poorly developed, Vitti fails to convince as an action heroine, and Dirk Bogarde’s camp super villain Gabriel is frankly an embarrassment. Only Terence Stamp as Modesty’s loyal sidekick Willie Garvin emerges with any credibility. As a result Modesty Blaise is the great lost opportunity of British comic strip movies.

Even so it had a surprisingly positive critical reception. The Monthly Film Bulletin felt that it perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the mid-1960s: ‘If a social historian were faced with the task of citing the film most representative of the spirit of the age, Modesty Blaise would be a strong contender. The film is a paean to the mid-sixties, the age of the ephemeral, the use-it-and-throw-it-away phenomenon, the era of the colour supplement, of paper plates and plastic toys and colourful gimmickry in the visual arts.’ The more serious and middle-brow critics seem to have welcomed it as a parody or deconstruction of the gimmicky secret agent movies exemplified by the Bond pictures. The broad approval at the time (it’s pretty much rubbished today) is revealing about a too-dogmatic adherence to the auteur theory: Losey was a critics’ director, and there was a sense in which he could not (at the time) be deemed to have made a bad film. But Peter O’Donnell was keen to distance himself from the film of which he later said: ‘It makes my nose bleed just to think of it.’

Modesty Blaise

James Chapman is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Leicester and author of British Comics: A Cultural History (Reaktion, 2011) as well as several books on British cinema, including Licence To Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films (I. B. Tauris, 2nd edn 2007) and Hitchcock and the Spy Film: Authorship, Genre, National Cinema (I. B. Tauris, 2018). He is currently writing Comics at the Movies, a history of comic book film adaptations from the Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s to the contemporary Marvel and DC superhero cycles.