The Early Development of the Comic Strip in the UK (Part 1 of 2) by Roger Sabin & Michael Connerty

/Tom Browne, "Weary Willy and Tired Tim", Comic Cuts, 24 July 1897

Michael Connerty

Okay, so what is there to say about the British comic strip in the final decades of the 19th century and into the early 20th? Firstly, whereas the strip in America evolved principally in the context of the newspaper and the Sunday supplement, in the UK strips came in the context of publications like Comic Cuts, The Funny Wonder and The Jester, which were much more specifically oriented around laughs, thrills and entertainment. One of the most striking characteristics of the British comics of this era is their variety of content. I think you can see the chaotic arrangement of elements on the page, all vying for the reader's eye, as a kind of metaphor for the intense vitality of urban life at the end of the century. The comic strip is just one component in amongst this jumble- though it would become increasingly dominant over the course of the 1890s, and would come to define these publications into the new century.

A big influence on this form were the hugely successful text-based publications like George Newnes's Tit-Bits and Alfred Harmsworth's Answers to Correspondents, both of which were stuffed with easily digestible factoids, anecdotes, historical tales, scientific curiosities, amusing trivia and early examples of celebrity gossip, in an apparently random flow of information, aimed at a mass readership. Some of this kind of material made it into the comics too, alongside pages crammed with humorous graphic imagery in the form of strips, but also single panel cartoons, many of which were lifted, without permission, from other sources, including American and European periodicals.

Almost all of the comics also featured literary serials- with dramatic, and occasionally lurid, illustrations, linking the comics to the penny dreadful that preceded them, but also to contemporary forms of popular fiction- tales of crime, espionage, mystery and adventure. A lot of these illustrations, in a realist rather than a cartoony style, justify the cover price on their own! The strips themselves often riff on the tropes associated with these genres and there is an intertextuality at work with formal and narrative references to a wide array of contemporary media and entertainment, including the circus, music hall (the UK version of vaudeville), popular theatre and, from the mid-1890s, cinema.

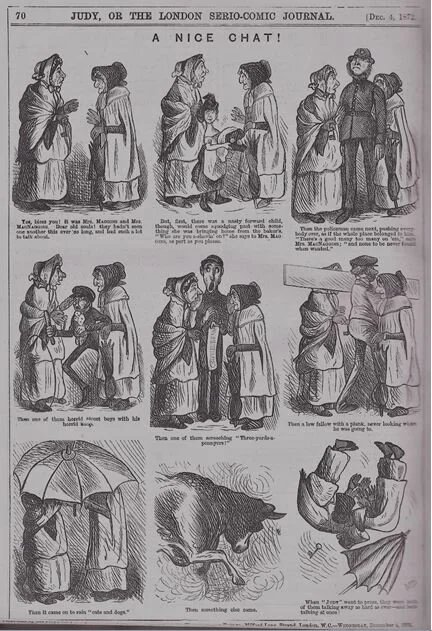

Marie Duval, 'A Nice Chat!', Judy, 4 December, 1872

Roger Sabin

We obviously share a love of the speed-freak bonkers-ness of these publications, and I agree with everything you've said, but would like to problematise it in two ways. First, strips were around a long time before Comic Cuts et al. I know you wouldn't disagree with that, but I'd like to give a shout-out to people like Heath, Cruikshank, Doyle, Leech, Tenniel, Ross and Duval, who were tickling people's funny bones with sequential panel narratives right through the 19th century.

Second, if we base our discussion of British comics around 'strips', then isn't that trying to fit them into a particular box? Isn't it more helpful to think of them as miscellanies, as you expertly describe? So, for example, Brian Maidment has tracked the history of humorous miscellany-style magazines in the early 1800s, and we can go from there to Punch and the Punch rivals (Judy, Fun, Tomahawk, etc.) then to Ally Sloper's Half-Holiday and all the imitators of that groundbreaking publication, and then to Comic Cuts and the 1890s funnies.

I guess this is a question - or series of questions - about history. Yes, there was an evolution towards the (UK) comic as a strip-based publication (if we take The Beano - founded 1938 - as our standard British reference point). But that's only one trajectory: an obvious counter-example might be something like Private Eye (founded 1961) which is a satirical miscellany in the old tradition (and which nobody calls a comic). All that leads us to the question of the moment at which there was 'genre consciousness', i.e. comics were accepted as comics. I presume from the above that you might choose the 1890s, with Comic Cuts being the archetype, and I might take things back to the 1880s with the Half-Holiday and its copyists.

Either way, there's the question of 'strippy-ness', and I know that both of us are interested in aspects beyond strips e.g. how those literary serials you mention were illustrated. If we get too focused on just one thing, then we miss... well... too much. (That's a critique that could be levelled at comics studies as a whole, I think.)

One thing we do seem to agree on is that the explosion of these publications was a product of circumstances having to do with the unique status of the UK at that time. Victoria's empire was the most powerful the world had ever seen, and by 1900 London was the largest city in the world. The infrastructure for what we might call modern entertainment capitalism was there early-on and was sophisticated compared to other parts of the world. Hence, as you mention, the incredible music hall/variety scene, the boom in photography and later film, and in cheap publishing - including comics. I'm not making any kind of nationalistic point here; just indicating that when you look over to the US, and start to make comparisons, that might not be germane because urbanisation and entertainment capitalism were taking different forms there.

Oliver Dawney, "Deep-Sea Fun", in Puck, 22 October, 1905

Michael

Yes you’re right about the perils of having too narrow a focus with these things, particularly true in the case of the neglected single panel gag cartoon. They have traditionally fallen between critical stools, but surely the most obvious scholarly home for them is within the warm embrace of an expanded comics studies. You can see all kinds of examples of comics ‘language’ on display in the gag cartoons, and they share so much in terms of graphic style and the development of the cartoon sensibility. The Oliver Dawney one above is a fine example of the noble art.

There is a self-consciousness around comics as a specific publishing category, which emerges a bit more fully during the 1890s, and is then pretty much consolidated by the turn of the century. I totally agree that the artists contributing to the comics during this period exist on a continuum with earlier cartoonists, illustrators and caricaturists (as in the US, individual artists probably didn’t distinguish much between these various activities at the time, and many were adept in all of these areas), but there are certain elements that begin to predominate- recurring characters, sequences of panels, word balloons, a particular graphic style- albeit that these weren’t necessarily appearing for the first time during that decade. It’s worth noting that a number of the comics included reprints of well-known American strips by the likes of Frederick Opper and F.W. Outcault, which definitely had an influence on British cartoonists, such as Julius Baker (below).

Julius Baker, "The Cinderella Season Has Commenced in Casey Court," Illustrated Chips, 20 January 1906

In the same way that Hearst and Pulitzer were instrumental in providing platforms for American strip artists, a future press baron called Alfred Harmsworth (later “1st Viscount Northcliffe”) was a key figure in the development of comics as a mass medium in the UK. He would go on to have great success as a media mogul, establishing the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror for example, but he achieved his earliest successes with comics. Because Harmsworth and his peers were so intent on shifting as many units as possible, there’s an open and accessible style of address at work that seems to be aimed equally at men and women, working class and middle class, young and old. There’s almost no reference at all to party politics- Harmsworth didn’t want to alienate any potential purchaser. There is plenty of flag-waving Jingo-ism, particularly during the South African War (1899-02) and later during WW1. A corollary of this is that, as elsewhere, the pages often contained ethnic and racial stereotypes that reflected the Imperialist world view predominant in British popular media at the time.

Harmsworth believed passionately that what he called “the age of cheapness” had arrived- the comics were part of the same popular commodity culture that included the joke shop novelties and mail order cures for baldness regularly advertised in their pages. One of Harmsworth’s most important moves was the dramatic reduction in the price of his titles to the rock bottom half-a-penny. Hundreds of thousands of copies were purchased every week, far outstripping the readership that had existed for humour periodicals during the previous decade. Harmsworth also saved a lot of money by skimping on ink and printing quality, and by using very low-grade paper. This has meant that surviving copies are often in pretty poor condition- tiny shards of brittle paper litter the table after even the most careful perusal through library volumes. There is an urgency around the archiving and preservation of this material. It’s all split between the British Library, the Bodleian in Oxford, and various regional and local libraries at the moment. It would be great to see a comics-specific archive of material from this period.

Roger

Oh, I agree about cartoons - so overlooked, and so fascinating. They factor into the previous point about a historical progression towards 'comics': I forget who it was that observed that in many cases they were seen as progressive/adult/forward looking, for the way you could play with the juxtaposition of word and image, and that strips were seen as clunky and old school in comparison, even looking back to the kids' books of the 1860s. Once again, there's no linear evolution. Similarly, as you hint, early creators would not have perceived themselves as 'cartoonists' or ‘strip artists’; rather, as artists doing a job that involved several kinds of cartooning. (The word 'cartoonist' only enters the Oxford English Dictionary in 1893.)

As a sidebar, I’ve been collecting scrapbooks from this period lately, and scrapbookers loved chopping up comics, but were not particularly interested in strips; they wanted illustrations and cartoons, because then they could customise their own pages.

I also agree about American influence. By a certain point in time, it's everywhere. But, as you say, it's often in hybrid form - a little bit like in the 1940s when bebop came over and was reimagined by London musicians. I also agree about Harmsworth. What is interesting about him, in retrospect, is the way he changed everything from the bottom up. As you say, there's his obsession with cheap ink and paper, etc., but what's less acknowledged is the way he utilised an army of street sellers. He revolutionised distribution as much as anything. The old idea of the family firm, with paternalistic ties to staff and newsagents, which was a characteristic of the Half-Holiday and its publisher, was blown out of the water in favour of a new brash capitalism that emphasised *hustle*. Harmsworth would put dozens of titles out there to see which ones survived, and would launch comics tactically to destroy rivals. So although the 'Harmsworth Bros' started out as a family firm, this model very soon morphed into something more aggressive, and faster.

That had big consequences for the content of the comics, I think, and not just in obvious ways like the kinds of characters that were foregrounded, and the 'borrowing' of stuff from the US. For example, I'm interested in the turn against world-building. Whereas previously the Half-Holiday attempted to build a universe (i.e. the endless soap-opera of the Sloper family), and invested in an albeit crude week-by-week continuity to keep people interested, now we were into an era of what I'd call 'assemblage comics' - cheapo publications thrown together from here-and-there, with the aim of being enjoyed in the moment (rather than asking the readership to put in some effort). The Half-Holiday had also built a world outside of itself - with Sloper merchandising and stage shows, which were then referenced in the comic - and this idea, too, was pretty much ditched in favour of print-focused speed and immediacy ('100 Laughs for a Halfpenny!', as Comic Cuts had it). Some of the new comics paid more attention to editorial branding and direction than others, it was true. But the idea of the 'classic' interchangeable, cheap-and-cheerful, British comic was pretty much an 1890s thing.

Oh, and on your final point, I know what you mean about archiving these comics. I was in a library looking at an historically important title called Illustrated Bits, and it literally fell to bits. Sad...

Professor Roger Sabin is Professor of Popular Culture at the University of the Arts London. He is the author or editor of seven books, including Adult Comics (Routledge 'Major Works') and Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels (Phaidon), and he is part of the team that put together the Marie Duval Archive (www.marieduval.org). He is Series Editor for the booklist Palgrave Studies in Comics, and 'The Sabin Award' is presented annually at the 'International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference'.

Dr Michael Connerty teaches film and animation history at the National Film School (Dun Laogahire Institute of Art, Design and Technology) in Dublin. He recently completed his PhD at Central Saint Martins, UAL, where his focus was on early British comics, particularly the work of Jack B. Yeats. His writing on comics history has been published in the International Journal of Comic Art and in the collection Comics Memory: Archives and Styles edited by Maaheen Ahmed and Benoit Crucifix (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).