Remembering UK Comics: A Conversation with William Proctor and Julia Round (Part II)

/‘THE BASH STREET KIDS,’ THE BEANO

JR

When I was reading comics like Jackie I don’t remember any credits at all though, and I certainly didn’t know enough about the creators to follow anyone in particular. I barely recognized celebrities in the photos strips! (and there were some fairly big names, though often before they were famous - that’s George Michael below). Jackie always felt more like a magazine than a comic to me though - I mostly remember its articles (on anything from anorexia to crafting), pop music features and interviews, and of course tons of quizzes (how else would I have known what sort of personality I had or how to attract the right sort of boy?!)

George Michael stars in this photo strip from Jackie

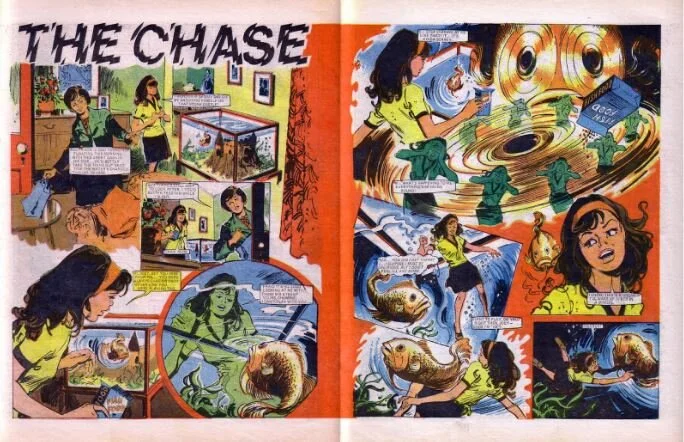

So my awareness of British comics creators has been almost entirely retrospective, a bit like yours I think. It’s been an amazing journey of discovery! I’m still not great at recognizing art, but the range of styles and techniques and layouts in these comics is spectacular. Some of the pages are mind-blowing! — notions like tiers and grids simply didn’t seem to exist for these artists.

‘The Chase’, Misty #40 (art by Douglas Perry, writer unknown)

‘The Loving Cup’, Misty #71 (art by Brian Delaney, writer unknown)

WP

That’s a great point about artistic styles, Julia. Again, at the time it would have just seemed typical to me, and while breaking the structural ‘rules’ of grids and tiers has become quite common nowadays, often with critics describing such exploits as innovative (especially in superhero comics). But it’s not something I’ve given much consideration to be honest (and certainly not at the time).

JR

There’s a lot of variety! Some artists did always go in for quite static layouts of course - regular rectangular panels laid out in three tiers. Some of the DC Thomson titles in particular might include things like a snippet of dialogue captioning the whole page (‘Dad! You can’t mean it!’) - for me, this can make the events feel a bit more like summaries and slows the pace. But a lot of the girls’ comics had crazy layouts! All those gymnasts and swimmers meant dynamic action that could be used to break up the page. Doug Church’s role as art editor of 2000AD led a big push towards splash pages and large opening panels that definitely fed into titles like Misty in the late 1970s, but I think the impetus was always there.

‘Bella’, Tammy (written by Primrose Cumming, art by John Armstrong)

WP

Thanks to Professor Martin Barker, I now have a complete run of the 1970s’ comic Action, which caused quite a controversy stirred by the media ‘harm brigade’ (the more things change, and all that). It is my favorite UK comic overall, but that came much later after I read Barker’s Comics, Ideology and its Critics (1989). I won’t go into that here as we have an essay upcoming focused on the title, and an interview with Martin Barker himself, but I think it’s interesting that comics tapped into successful films, much in the same way that so-called ‘exploitation’ cinema did. Spielberg’s Jaws led to a cycle of ‘Sharksploitation’ and ‘nature-run-amok’ films, like William Girdler’s Grizzly (1976) -- which lifts its plot from Jaws, but replaces the Great White with an 18-foot tall grizzly bear! -- Michael Anderson’s Orca (1977), Joe Dante’s Piranha (2000),and many, many more, all the way into the new millennium with the Sharknado franchise. But UK comics tapped into successful film cycles as well, like Action’s ‘Hookjaw,’ a bloody intertextual remix of Moby Dick and Jaws.

‘Hookjaw’ from Action

It seems to me — and I’m sure scholars have mentioned this before me--that comics also drew from the exploitation model of latching onto the coat-tails of popular cinema. Another example that springs to mind comes out of your research into Misty, Julia! I’m thinking of the strip titled ‘Moonchild’ by Pat Mills and John Armstrong, which is a thinly-veiled riff on Stephen King’s Carrie; although as Simon Brown points out in his Screening Stephen King, without Brian De Palma’s 1976 adaptation, King probably wouldn’t be the house-hold name he is today! So I’m guessing that it was De Palma’s film that ‘Moonchild’ is responding to rather than King (at least directly).

JR

Absolutely — the Misty serials in particular seemed to rearticulate texts from all over the place. As well as ‘Moonchild,’ Pat Mills wrote a serial called ‘Hush, Hush, Sweet Rachel’, which takes its plot from Frank De Felitta’s Audrey Rose (1975, also adapted into a film in 1977). ‘End of the Line’ (Malcolm Shaw and John Richardson, #28–42) draw on the movie Death Line (1972), where people are kidnapped by the cannibalistic descendants of a group of Victorian tube tunnel workers trapped underground. Of course, sometimes the recycling is little more than a name-check to create an atmosphere: ‘Whistle and I’ll Come,’ which recalls M.R. James’s ghost story ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’ (1904) which was made into a UK television adaptation in 1968). ‘Hush, Hush, Sweet Rachel’ is a portmanteau of the movie Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), a psychological thriller about infidelity and a falsely accused murderess, and the TV movie Sweet, Sweet Rachel (1971), a pilot for a series about a murderer who uses extrasensory perception. And ‘The Four Faces of Eve’ (Malcolm Shaw and Brian Delaney) name-checks the 1957 movie The Three Faces of Eve, which is about dissociative identity disorder. So intertextual references were very common, even if only used as a knowing nod to source material or to conjure a mood.

WP

Although I’m aware of academic work on UK Comics—James Chapman’s British Comics, Mel Gibson’s Remembered Reading: Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of British Girlhood, and Martin Barker’s Comics, Ideology and its Critics are three of my personal favourites—I often wonder if some of the UK Comics’ history is in danger of being forgotten. There are surely reams of publications that have yet to receive academic treatment (I am unaware of work on comics like Champ and Scream, two of my nostalgic objects). Of course, you have your new book on Misty coming out soon as well! Mazel tov!

Is that a fair assessment of the field do you think, Julia? Are we in danger of losing our national memory about UK Comics to some degree?

JR

Definitely. Few people thought any of these comics (particularly the girls’ titles) were worth preserving or collecting, and I’ve heard loads of horror stories of original artwork being used as cutting boards, or comics being used to mop up archive floors, or thrown into skips (when Fleetway moved offices), or just given away outside conventions. Mel Gibson’s research into readers’ memories and oral histories actually started because she found that the comics themselves were so hard to get hold of! When big private collections have appeared (such as Denis Gifford’s, after his death) they’ve been split up and sold off. I’ve been part of a number of (rejected) bids to try and get some national research money behind preserving some of these collections, and I’m speaking at a public event next weekend (Saturday 2 November) at the Cartoon Museum in London that is trying yet again to drum up some interest in this. We need to protect and preserve these publications and their ephemera, whether through digitisation or creation of a physical archive. There isn’t anything about today that looks or feels (or smells!) like old British comics — they really are relics of a bygone age, not to mention an important part of our national memory. They have so much to tell us about society from almost every angle — ideology, gender roles, politics, economics, social norms, other media, and much much more.

Plus, did I mention that the stories and artwork are awesome?!

BP

It’s certainly a history that is worth preserving, and I’m sure that there are many titles that have fallen through the academic gap (and perhaps will continue to do so). And yes, the stories and artwork are awesome (sublime, even)!

I’m sure some readers may find the idea of ‘smell’ quite odd, but when I sniff an old comic, I am immediately catapulted back through time as if at 88 miles per hour in a Delorean; back to a simpler time, of a childhood spent indiscriminately gorging on a bevvy of titles, often picked up at a jumble sale hosted by a local church (in my experience). I remember ink-stained fingers as I delivered comics and newspapers—and the odd porn magazine—on my paper route. I remember Dennis the Menace terrorizing his dad, who would react spectacularly by chasing Dennis with his weaponized slippers. I remember Judge Dredd shooting up another block party, Slaine slicing and dicing his enemies, a thinly-veiled analogue of Robert E. Howard’s Conan. I remember laughing at the various strips in Whizzer and Chips, Cor!, Buster, etc.; gasping at the latest twists and turns in Roy of the Rovers; shivering in terror at ‘The Thirteenth Floor.’ I remember reading my sister’s Jackie, Mandy, and Bunty. Gender didn’t matter in what I read—I was and remain a comic book omnivore— yet it mattered enough not to openly declare my eclecticism to friends for fear of masculine reprisal in the school playground. I remember it as the best of times during the worst of times (I grew up in Thatcher’s Britain, so nuff said).

DENNIS THE MENACE AND GNASHER FROM THE BEANO

At the beginning of this conversation, I did caution that I would be likely to wax lyrical! My memories of reading as a child, and as a teen, are precious. Without the education provided by comics, I’m not sure I would be such an energetic and avid reader as I have been throughout my adult life. (Bryan Talbot once said that he learned to read through comics, so I know I’m in good company.)

STRONTIUM DOG FROM 2000AD, ART BY CARLOS EZQUERRA

In essence, this series of essays on UK Comics aims to spotlight at least some of the medium’s history. As such, we have curated a lively series of essays that will hopefully reach those readers for whom UK Comics are forgotten relics, or to share a range of perspectives on a medium that people may not be aware of. We hope you’ll join us on our voyage into the dog-eared, pulp-inflected, yellow-stained past as we remember the wonderful, eclectic, intelligent, and insane world of UK Comics.

Next week, we begin with Dr Mel Gibson on girl’s comics. Join us, won’t you?

Dr William Proctor is Senior Lecturer in Transmedia at Bournemouth University, UK. He has published widely on various topics related to popular culture, including Batman. James Bond, Stephen King, Star Wars and more. William is a leading expert on franchise reboots, and is currently writing his debut monograph, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, and Transmedia Histories (forthcoming, Palgrave). He is the co-editor of Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman, Routledge 2018), and Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Promotion, Production, and Reception (with Richard McCulloch, University of Iowa Press 2019).

Dr Julia Round is a Principal Lecturer in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, UK. She is one of the editors of Studies in Comics journal (Intellect Books) and a co-organiser of the annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference (IGNCC). Her first book was Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (McFarland, 2014), followed by the edited collection Real Lives, Celebrity Stories (Bloomsbury, 2014). In 2015 she received the Inge Award for Comics Scholarship for her research, which focuses on Gothic, comics, and children’s literature. She has recently completed two AHRC-funded studies examining how digital transformations affect young people's reading. Her new book Misty and Gothic for Girls in British Comics (forthcoming from UP Mississippi, 2019) examines the presence of Gothic themes and aesthetics in children’s comics, and is accompanied by a searchable database of all the stories (with summaries, previously unknown creator credits, and origins), available at her website www.juliaround.com.