Comics, Childhood and Memory—An Autobiography (Part I of 3) by Mel Gibson

/Comics, Childhood and Memory: An Autobiography (1 of 3)

Mel Gibson

Everyone writes and re-writes their autobiographies as they remember, in a continual process of selection and construction. As Annette Kuhn (1995) described it, memory is ‘driven by two sets of concerns. The first has to do with the ways memory shapes the stories we tell, in the present, about the past-especially stories about our own lives. The second has to do with what it is that makes us remember: the prompts, the pretexts of memory; the reminders of the past that remain in the present (p.3). Some of my childhood memories are anchored by what I was reading to a specific place and time, in line with what Kuhn suggests, as having been an enthusiastic comic reader generally means that I have a timeline of my childhood, given that they were typically bought new or second-hand shortly after publication. It also means that comics are tied in a direct way to memory, something which as an ‘aca-fan’ became linked with the practice of object elicitation, of using comics as objects in interview.

As a British child born in 1963 in the North East of England my memories of comics incorporate a wide range of texts, including material like Rupert the Bear and Teddy Tail, anthropomorphic narratives which originated as newspaper strips. I also had access to imported superhero comics, which my father bought for me (or perhaps for himself with me as a secondary, pass-along, audience). These were exclusively DC titles, especially Batman, The Flash and Justice League of America. They were aimed at an audience much older than I was when I first read them, with him, as an under five year old. The combination of comics featuring adult characters and a parent who was around only intermittently, given that he was studying art in London, was potent, giving those comics a heightened significance. That he also used elements of them in art works stressed their importance too and may have contributed to my interest in comics as an ‘aca-fan’.

However, I also had access to comics in the form of annuals that had been gifts for my mother as a child. These annuals related to a gender specific title called Girl, a weekly periodical which had specific class and gender signifiers. More costly than many of the other titles available, and partly printed in four colour rotogravure on comparatively high quality paper, it was also a broadsheet. The majority of titles for girls, in contrast, were tabloid and although they might feature a cover in colour, were usually printed in black and white, with occasional uses of red as a spot colour (see Figure 4 for an illustration of this). All of these physical qualities attached to Girl could be seen as signifying the middle-class nature of the periodical. Who the audience actually was is not so fixed, but the intention was, whoever the reader, to guide their aspirations. It is Girl and the genre that it belonged to, the British girls’ comic, which will be the focus of the majority of this article. I would add that I am focusing down further still, on titles that were aimed largely at younger readers, rather than those in their teens.

The robust annuals, part of the wider culture and marketing around comics, along with toys and a range of other materials and events, were a staple Christmas gift in British households throughout the late twentieth century. The annuals I got to read had been published in the 1950s and contained a mixture of other materials alongside comic strips, including prose narratives. These earlier British publications linked me with both my mother and grandmother through forming the basis of some of our shared reading and family history. As Kuhn states, ‘an image, images, or memories are at the heart of a radiating web of associations, reflections and interpretations’ (1995, p.4).

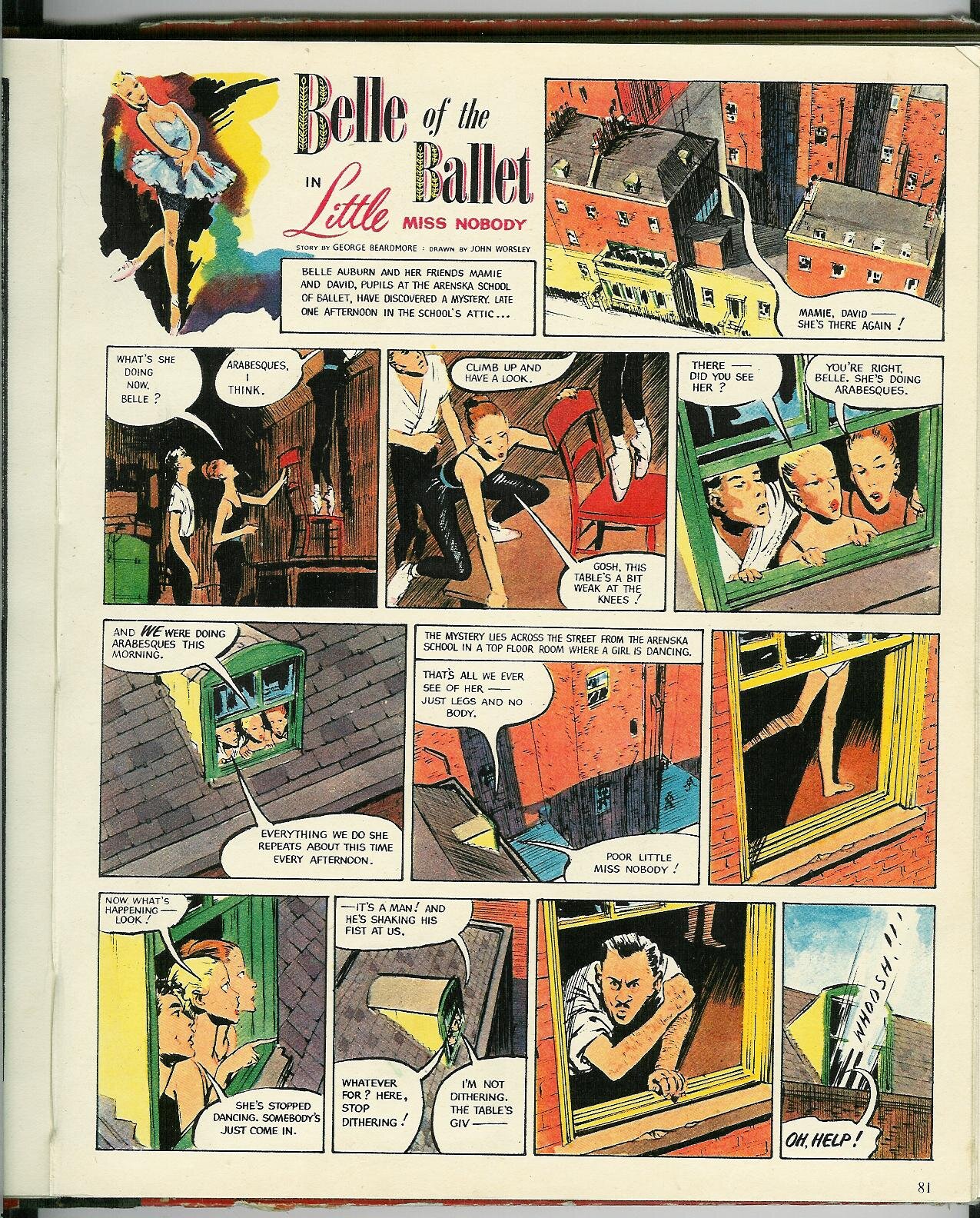

Engaging with both the superhero comic and the girls’ comic, two very different comic traditions, meant that they became juxtaposed in my mind. Both inhabited what seemed to be gendered spaces and readerships and, indeed, almost appeared to be capable of being used as tools to mold me into a ‘proper’ girl or boy. Both also seemed to contain characters whose activities were linked with gender. I was, however, most drawn to stories in Justice League of America and to one in particular in Girl, entitled ‘Belle of the Ballet’. Whilst the content is very different, what drew me in was that the male and female characters had shared aims and objectives.

The example shown below, which I have analysed in depth elsewhere (2008), is a complete short story from an annual (in the British weekly anthology comics stories could run for twelve weeks or more, each week ending with a cliff-hanger). What is important in this context is that David, the male dance student is a regular character who trains and performs alongside Belle and Marie. He does not dominate the stories, but is simply part of their friendship group. In this example the friends investigate a dance focused mystery where class and the acceptability of dance are also key themes.

This narrative and others about Belle and her friends, the encouragement of family members and the increased cultural interest in ballet as a socially appropriate activity resulted in my taking ballet classes when I was around five. This ended rather swiftly when stage fright and the theft of my Twinkle comics from the dressing room after a performance resulted in my refusing to go back to classes again (or read that comic).

‘Belle of the Ballet in Little Miss Nobody’. (Girl Annual 3, Hulton, 1954, pp. 81-84)

The stolen copies of Twinkle flag up another set of references, as well as memories. It was a British weekly title which was sporadically bought for me and formed a dramatic contrast with the superhero titles. It was an important title for very young girls and, I believe, the only nursery comic that consciously addressed a gendered audience, as indicated by the way that the strap-line after the title ran, ‘specially for little girls’. Accordingly, it often had similar content to titles for older girls, including a focus on work. For instance, Twinkle featured a narrative about ‘Nancy the Little Nurse’, who helped her grandfather mend toys. I returned to this comic and that narrative in 2008, in writing about the many tales about nurses that appeared in British girls’ comics. Twinkle also featured a number of magical friend stories and a range of activities including a cut out doll.

‘Nancy the Little Nurse’ (Twinkle, No. 362, 28th Dec 1974)

I fear that as a child I felt the material in the girls’ titles was somehow constraining in comparison to the content of superhero comics. It was only later, in researching girls and comics, that I became fully aware of the diverse narratives that existed and that these titles were often ground-breaking in terms of both approach and content. Engaging with girls’ comics as an academic, in hoping to understand what these texts meant to readers, helped me grasp the complex nature of the genre and how readers understood those comics, using them as identifiers of self, often in opposition to monolithic readings of girlhood and the girls comic. However, as a child with limited funds to draw on, I simply opted for what I saw as more exciting and less directive. The full color in the superhero titles was also, I admit, an attraction.

However, to return to memory, in largely rejecting British girls’ comics as a slightly older child (preferring, by the mid-1970s, as I entered my teens, the X-Men and Franco-Belgian albums in translation, particularly Asterix, Lucky Luke and Tintin) I was consciously cutting myself off from what was a major genre and shared cultural experience. I now suspect it was also an attempt to disengage from British girlhood and what I saw as the expectations surrounding it. It was also about this time that I became an avid reader of science fiction for adults, which further moved me away from girls’ culture.

To put the scale of this rejection in context, British girls’ comics existed for every age group, as the depiction of the characters in the two narratives above suggests. These weekly anthology publications formed the majority of reading of most British girls between the 1950s and 1990s, with over fifty titles existing through this period and major ones circulating between 800,000 and a million per week. It was, in effect, the dominant form of comic aimed at girls, and created a potential feminine reading trajectory that ran from Twinkle, through Bunty and similar titles aimed at those under twelve, to titles for older readers focused on heterosexual romance and popular culture such as Roxy in the 1950s, and later Jackie and on to magazines. What is also significant about these narratives is that romance only featured in titles for older readers and the worlds depicted in girls comics were about their friendships and rivalries, not about boys.

The narratives they included changed over time especially from the late 1970s to 1990s, some becoming rather bleaker and horror-inflected and others opting for realism via the inclusion of photo stories. Further, a number were slowly converted into magazines, reflecting what were seen as changing interests amongst girls. This shift also served to emphasize that comics were for boys, which the sales figures for girls’ titles actually contradicted. However, as I became a teenager, I was increasingly uncomfortable about talking about my interest in comics, as cultural assumptions about reading meant that I was often told to read magazines for older girls or women instead. Additionally, actively seeking out superhero comics put me firmly in a male zone, including one specialist shop where I was known as ‘the girl’, and seen as a rarity. This meant that I inhabited a liminal zone around popular periodical reading and gender.

To return to the kinds of narratives that existed, the titles for younger readers featured a number of dominant types. There were schoolgirl investigators, school stories of various kinds, work related stories, those tied to popular activities like ballet, ice skating, horse riding or gymnastics and ones about friendships. They also contained ghost stories, ones where girls had magical friends, rags to riches narratives, and tales about animals of various kinds. There were, in addition, forays into science fiction and fantasy, with a number containing heroines with magical or other powers. The umbrella of the girls’ comic, then, had a very diverse range of material beneath it. The following examples give a small indication of some of what was available.

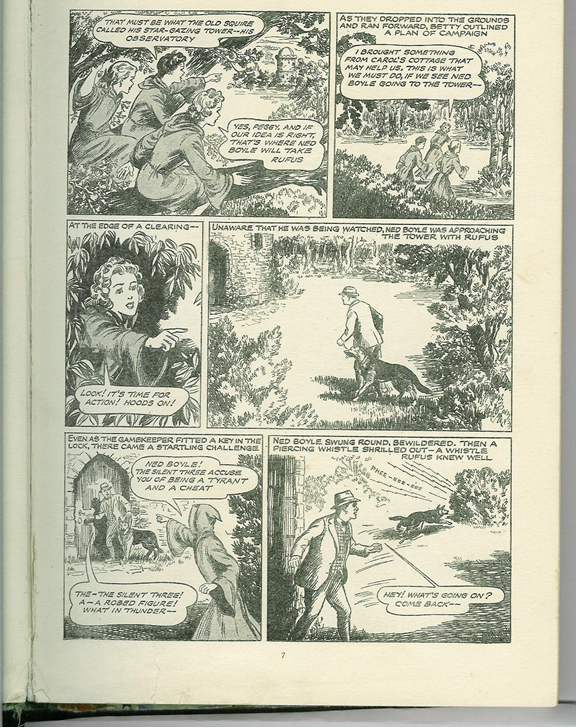

I begin with ‘The Silent Three’, an example of the girl investigator narrative and one of the most popular narratives in what was one of the most popular titles for girls in the 1950s. Whilst the majority of girl investigator narratives do not incorporate costumes, here the three friends wear matching domino masks and cloaks. The friends’ activities are also part of a type of secret society at school. Consequently, investigative narratives in this particular story run alongside ones about everyday school life, including school bullies attempting to either find out about or discredit those in the society. This has some obvious links with concepts in the superhero titles including the vulnerability of the hero and the secret identity. This is despite the private all-girl school and middle (or upper middle) class context of the narrative. The villains, as suggested in the images below, as well as the school bullies, may also be, like those in some Enid Blyton books, class ‘others’.

‘The Silent Three’. (School Friend Annual, AP, 1958, p. 7)

Dr Mel Gibson is an Associate Professor at Northumbria University, UK, specializing in teaching and research relating to comics, graphic novels, picturebooks and fiction for children. She has published widely in these areas, including the monograph (2015) Remembered Reading, on British women's memories of their girlhood comics reading. Her most recent work focuses on girlhoods, agency and contemporary comics. Mel has also run training and promotional events about comics, manga and graphic novels for schools and other organizations since 1993 when she contributed to Graphic Account, a publication that focused on developing graphic novels collections for 16-25 year olds, which was published by the Youth Libraries Group in the UK.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is edited by Dr William Proctor and Dr Julia Round.