British Comics Go to the Movies (Part 3 of 3) by James Chapman

/Judge Dredd (1995) is another example of the throw-the-kitchen-sink-at-it-and-hope-for-the-best school of film-making. This was another ‘Hollywood British’ film, produced in Britain by Carolco, the American independent which specialized in action movies such as Rambo and Total Recall. Rambo himself, Sylvester Stallone, was signed to play Dredd, the futuristic Dirty Harry created by John Wagner and drawn originally by Carlos Ezquerra for the cult British science fiction comic 2000AD. Again, this should have been a hit. Films such as RoboCop, The Running Man and Total Recall had suggested there was a market for futuristic violent action movies. The monosyllabic, uncompromisng lawman Dredd was perfectly within Stallone’s emotional range as an actor. And $80 million was a hefty budget, even in the spiralling cost-context of contemporary Hollywood blockbusters. But critics were dismissive in the extreme: reviews were headlined ‘Dredd boring’, ‘Dredd-nought’ and ‘A slice of stale dread’. And while it grossed around $112 million (with two-thirds of that coming from markets outside the United States), that was a disappointing return for a would-be franchise vehicle and probably meant that the producer did not recover the cost.

To be fair Judge Dredd isn’t nearly as bad as some of the other films featured here. It’s reasonably close to the source material, combining elements of two classic early Dredd stories, ‘The Day the Law Died’ and ‘The Return of Rico’. The production values are all one would expect and the Blade Runner-influenced cityscape of the future is a visual feast. It’s clear that Danny Cannon, the British director of The Young Americans, had an ambitious vision for the film. He saw it as an epic in the manner of Ben-Hur, Spartacus or El Cid: ‘Those movies took themselves very seriously, just as the artists acting in them did, and I tried to incorporate that element of emotional honesty in Judge Dredd. It’s every bit as much an epic passion play as it is a sci-fi film.’ This claim is not as ridiculous as it might sound. If we take Dredd as Judah Ben-Hur, Rico (Armand Assante) as the bad brother Messala and Chief Judge Fargo (Max Von Sydow) as the surrogate father-figure Quintus Arrius, then Judge Dredd does indeed resemble the structure of Ben-Hur, with Dredd’s journey on the prison ship the equivalent of Judah’s imprisonment on the slave-galley, the crash landing in the Cursed Earth the equivalent of the sea battle, and the chase on Lawmaster bikes as the chariot race. That Judge Dredd did not, in the end, match up to Cannon’s vision for the film was probably due to drastic editing in post-production – invariably a sign that someone (usually the studio) has doubts about the box-office potential of the finished product.

Yet ultimately Judge Dredd became a text-book example of the compromises that occur when Hollywood attempts to turn a cult comic strip into a would-be blockbuster. In the end it was probably not authentic enough to the comic source material to satisfy 2000AD cultists but too close for the general cinema-goers unversed in Dredd lore but who make up the larger proportion of the audience. Judge Dredd outraged fans when Dredd removed his helmet and even shared a kiss with Judge Hershey (Diane Lane). It would be unthinkable for him to do this in the comic but it was necessary for the film which had to appeal to a wider audience than merely readers of the comics.

Of course there are some pretty dire American comic book movies too. I recently sat through (in the name of research) the infamous Howard the Duck (1985), aka ‘Howard the Turkey’, an experience that the CIA could surely adopt as an enhanced interrogation method.

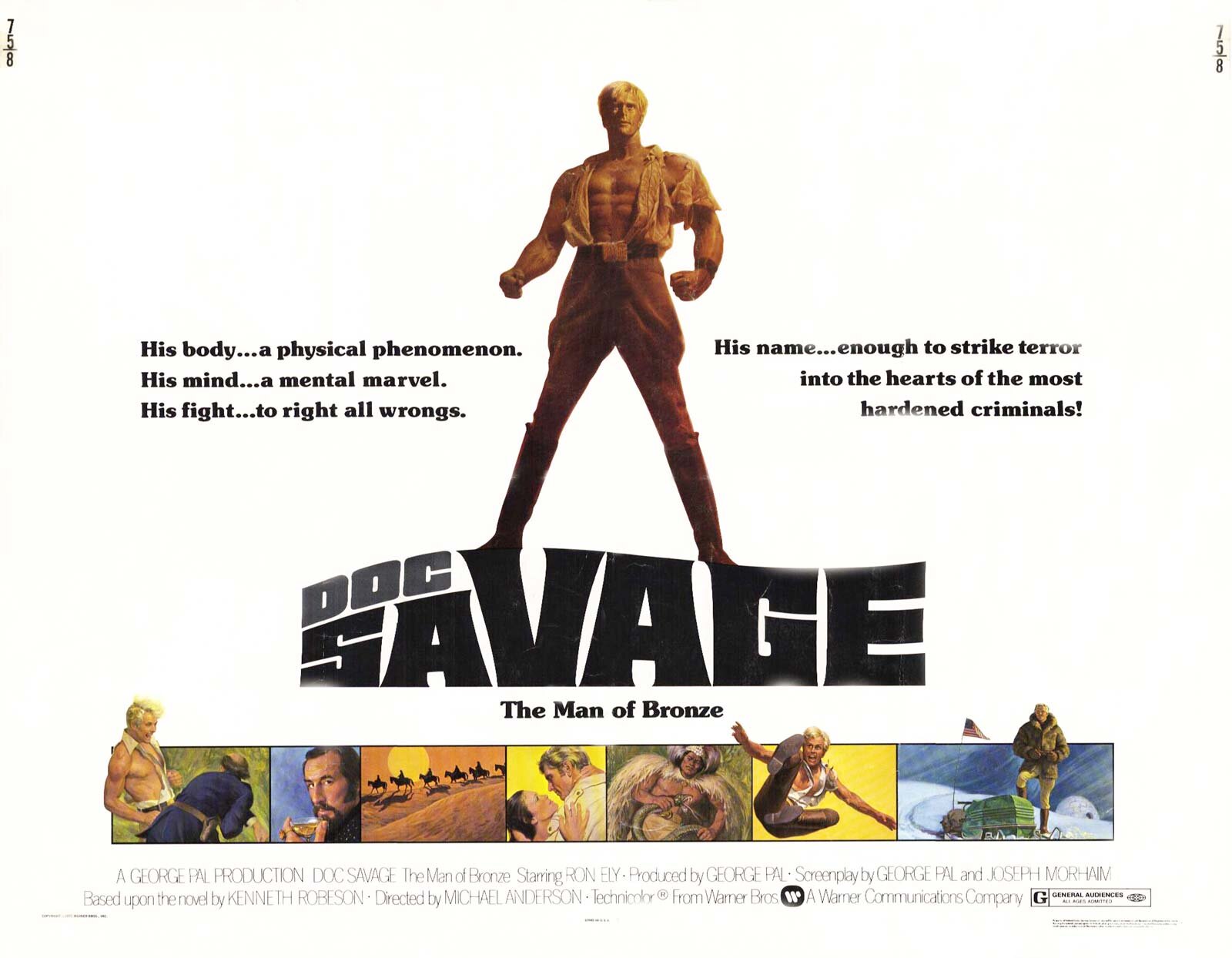

But there’ve also been plenty of good American comic book movies to erase the memory of the duds. Dick Tracy (1990) is one of the boldest visual design jobs in American popular cinema, The Rocketeer (1991) is a cinephile’s delight, and Wonder Woman (2018) finally disproved the theory that there’s no box-office potential for a female superhero. There are also many ‘guilty pleasures’: I’m a big fan of Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze (1975) (PM me if you want to know the storyline for the announced-but-unmade sequel The Arch Enemy of Evil, which I found in George Pal’s papers) and I rather like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) even though it was disowned by Alan Moore. And of course the continuing popularity of the Marvel superhero cycle – extending back to the first X-Men (2000) – has placed comic book movies at the epicenter of the political and cultural economy of contemporary Hollywood.

British cinema has long ceased to be a mass-production industry, and I very much doubt there is scope for production on the scale of Marvel Studios. But plenty of British comics would provide strong material for low or medium-budget independent films. The recent success of Sam Mendes’s 1917 might persuade an enterprising film-maker to take a look at Pat Mills and Joe Colquhoun’s ‘Charley’s War’ (Battle). Paul Grist’s Jack Staff would make for a quirky, offbeat, alternative superhero flick in the manner of Deadpool. How about Sky Atlantic or Netflix investing in a serialization of Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta for television? And I still live in hope that one day we might see that film of Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future.

James Chapman is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Leicester and author of British Comics: A Cultural History (Reaktion, 2011) as well as several books on British cinema, including Licence To Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films (I. B. Tauris, 2nd edn 2007) and Hitchcock and the Spy Film: Authorship, Genre, National Cinema (I. B. Tauris, 2018). He is currently writing Comics at the Movies, a history of comic book film adaptations from the Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s to the contemporary Marvel and DC superhero cycles.