More than Mere Ornament: Reclaiming 'Jane' (2 of 4) by Adam Twycross

/For the time being, however, Rothermere’s long shadow still fell across the Mirror and its contents, and as such, at the time of its first appearance Jane was obliged to straddle two competing ideologies. On the one hand, like every other aspect of the paper, the series was shaped by Rothermere’s right-wing conservatism; on the other it was cut through with a bawdy irreverence that was more in keeping with the ideological leanings of both Bartholomew and Pett. To a significant degree, the split allegiance that this necessitated was enabled by the social positioning of Jane herself within the fictional world of the strip. Although today remembered chiefly in its truncated form of Jane, Pett’s original title was both more loquacious and more descriptive; for the first six years of its existence, the series appeared as Jane’s Journal- Or The Diary of a Bright Young Thing. This title, the nuance of which would be lost on many modern audiences, would at the time have immediately established Jane within an existing ideological system that perfectly suited to Jane’s needs.

Although in truth something of a spent force by 1932, for much of the previous decade the Bright Young Things had provided the popular press with a steady stream of stories revolving around increasingly extravagant examples of aristocratic intemperance. The group had entered the public consciousness around the summer of 1924, when the Honourable Lois Sturt, the daughter of Baron Alington, had been arrested for speeding through Regent’s Park in the early hours of the morning. Sturt claimed to have been taking part in a game called ‘Chasing Clues’ that had been arranged by the previously unknown “Society of Bright Young People” (Shields Daily News 1924, p.3). Within months the groups’ name had became synonymous with a carefree and somewhat debauched style of youthful aristocratic play, with activities centering around extravagant games, opulent themed parties and, it was widely assumed, a liberal attitude to sexual congress, alcohol and the use of stimulants in general. Although largely composed of individuals from privileged, moneyed and aristocratic backgrounds, the Bright Young Things self-consciously rejected much of the ritualised and rule-bound etiquette that their elevated social position would usually have imposed on them, and instead absorbed influences from parallel and overlapping social subcultures that were less obviously aristocratic in nature. The inherent iconoclasm of the Bright Young Things’ rejection of societal norms gave them a compatibility with alterity of all types, creating a space in which young aristocrats mixed freely with homosexuals, artists, poets, and “tribes of girls answering to the loose description of ‘model’” (Taylor, 2007, loc.2073). The group’s particular affinity with the bohemian lifestyle, which had also proved so alluring to Norman Pett, was reflected in the contemporary press, who on occasion referred to the Bright Young Things’ activities as those of “high bohemia” (Ramsay-Kerr 1928, p. 4). Press interest in the group’s activities reflected an enduring public fascination that was heightened by inaccessibility. As well as foregrounding Jane’s social position, therefore, the series’ title and its formal construction dovetailed to create an alluring, if entirely apocryphal, sense of intimacy. The strip’s diary format, backed by first-person, hand-written narration, suggested a level of privileged access to the Bright Young Things, and to a world that remained otherwise closed to all but a small band of well-connected individuals.

Over the first few years of Jane’s existence, numerous strips reinforced the link between Jane and the iconoclasm of the Bright Young Things. Several strips featured a positively Sturtian disregard for road safety as a central narrative conceit, and Jane’s social life was shown to be a heady mixture of high and low pursuits that was perfectly in keeping with the Bright Young Things’ public image.

Pett 1934a

Jane, and indeed her contemporaries, seemed equally at home in an after-hours nightclub as at more formal gathering.

Pett 1933a

Jane also attended numerous parties, including the Chelsea Arts Club Ball.

Pett 1934b

This new year’s eve celebration had, by the early 1930s, become notorious for its riotous behaviour, and was described in contemporary accounts as “the last notable event of the old year in Bohemian circles” (Gore 1931, p.17). Like Lois Sturt, Jane’s portrait hung in the Royal Academy,

Pett 1933b

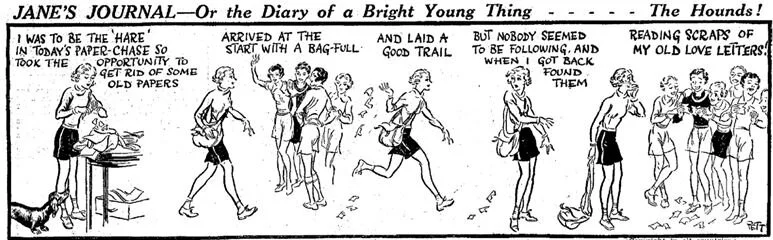

Several strips made clear that she and her social circle regularly indulged in precisely the type of urban treasure hunts that had first propelled the Bright Young Things into the public consciousness in 1924.

Pett 1934c

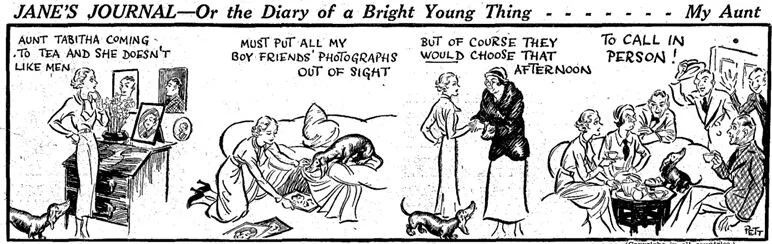

Although nudity and erotica was not yet a feature of the strip, it was clear that Jane’s youth and glamour facilitated a satisfying and varied love life that put her at odds with the decorum and propriety expected by her social circles’ elder generation.

Pett 1934d

The youthful and rebellious nature of the Bright Young Things therefore allowed Jane’s early years to feature an irreverent streak that reflected the liberal and somewhat unorthodox worldviews of both Bartholomew and Pett. Yet the social elevation and undoubted prosperity of most of the group’s members gave it a natural alignment with the systems and structures that supported and perpetuated the dominance of the ruling classes, and for all the raucousness of its subtext, Jane’s early strips also exhibited a clear affinity with the right-wing conservatism and social elitism of Rothermere. Being moneyed and cultured, much of Jane’s leisure time was filled with the typical pastimes of the young aristocrat; she regularly holidayed abroad, enjoyed trips to Ascot and relaxed in punts during the Henley regatta .

Pett 1933c

Although she was shown to be an attentive and generous friend, there was a sense that both she and her wider social circle looked down on the lower classes and their lack of sophistication. Some strips revolved around the ease with which their social inferiors could be seduced and manipulated into acting as Jane and her coterie desired.

Pett 1934e

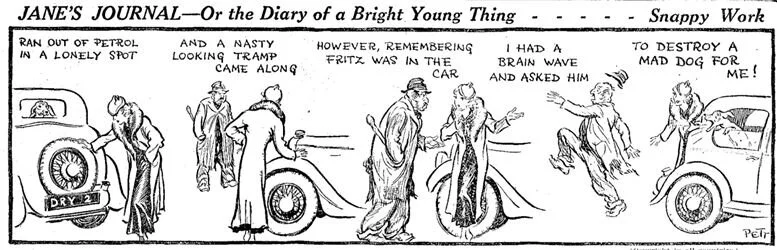

Other strips reinforced a hierarchically encoded worldview in which England was emphasized as pre-eminent amongst the home nations, and London repeatedly affirmed as its social and cultural centre. As a result the humour of many strips were built around an oppositional structure in which Jane’s cultured, sophisticated and urban worldview collided with the unrefined coarseness of her social inferiors. Consequently farmers, labourers, Scotsmen, the working classes and ‘nasty looking tramps’ were all ripe for mockery and derision .

Pett 1934f

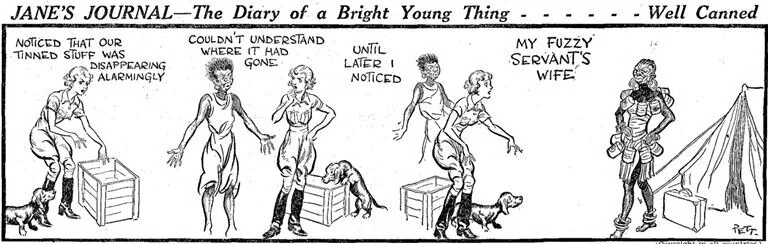

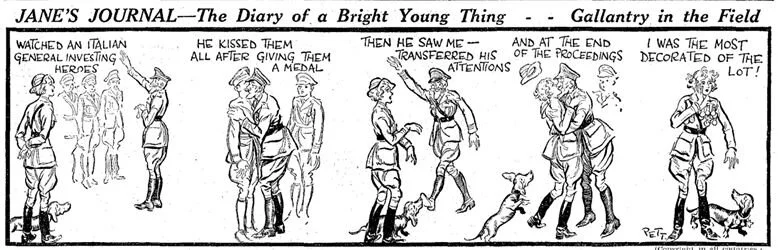

Strikingly, given the series later fame as a morale booster for allied servicemen, this same hierarchically aligned narrative structure was deployed to tacitly support Rothermere’s fascist leanings. In the early years of its existence, numerous Jane strips aligned fascism with Jane’s own cultured, sophisticated and ordered worldview whilst depicting the opponents of fascism as uncultivated, unsophisticated and brutal. In a series of strips focusing on the Abyssinian conflict, for example, Italian troops were depicted as well-equipped and glamorous; their Abyssinian counterparts were openly racist caricatures, depicted as primitive, dog-eating tribesmen who decorated themselves with discarded tin cans and deployed laughably inadequate military equipment (figs 13) .

Pett 1935a

Pett 1935b

Another strip saw Jane, resplendent in a new all-black outfit, mistaken for one of Mosely’s fascists by a braying mob of left-wing agitators. In the strip the mob appears likely to attack Jane, but their danger is nullified by the arrival of a Police Constable, narratively serving as an icon of law and order, who leads Jane to safety. The strips’ use of clothing as a storytelling device is telling. Pett’s choice of where to spot blacks provides an opportunity to link Jane and the Police Officer at a pictorial level, and serves to narratively associate the visual iconography of the Blackshirts with the unruffled composure of the British police force and with the sophisticated elegance of Jane herself. By contrast the undignified mass of left-wing protesters are depicted as a mass of lighter tones, their overweight and ageing members sporting either balding or unkempt hair and ill-fitting, baggy clothing which serves to accentuate their gracelessness. Other aspects of the Mirror’s address during this period echoed the gentle reinforcement of pro-fascist sentiment that this strip provided. The following month, for example, the Mirror’s sister paper the Sunday Pictorial ran an article by Rothermere eulogising the Blackshirts as a practical example of “patriotism and discipline”, and the Mirror ran prominent advertisements for the feature in the lead-up to its publication.

Pett 1933d

Adam Twycross is currently engaged in PhD research on the development and evolution of adult comics in Britain. Between 2012 and 2019 he was Programme Leader for the MA in 3D Computer Animation at Bournemouth University’s National Centre for Computer Animation, and has previously worked as a 3D modeller, with credits including the Xbox 360 title Disneyland Adventures and the Games Workshop graphic novel Macragge’s Honour. He is co-founder of BFX, the UK’s largest festival of animation, visual effects and games.