'Crisis on Inbetween Earths' (1 of 2) by Will Brooker

/In our final installment of our ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series, we have an essay by Will Brooker. Previously published on the now defunct website, Infinite Earths, Will has kindly permitted us to republish the essay in full, which we are very gratful for. I’m sure many scholars are intimately aware of Will’s work on Batman comics and other transmedia expressions in his Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon (Continuum 2001), and Hunting the Dark Knight: Twenty-First Century Batman (IB Taurus 2012), but he was also a dedicated reader of the Vertigo comics line of the 1990s, an imprint of DC Comics that would not have had such an impact on the medium without the armada of writers and artists that came with the so-called British Invasion. Indeed, what was Vertigo’s gain turned out to be e a great loss for the British comics landscape..

—William Proctor & Julia Round

Crisis on Inbetween Earths

Will Brooker

The year was 94. Or thereabouts. It was a slippery time; I dig out my old diaries from the attic and discover that some of this happened in 89, and some of it in 96. But I think of it as circa-94, around the time that Vertigo comics entered me and I entered them. I was living in a tall house with two or three other girls.

This is what it looks like now, on a digital map. But that isn’t how I remember it. I remember it more like this: like the scene of Rose Walker arriving at her new home in Gaiman’s second Sandman story arc, The Doll’s House. (Looking it up now, I realize it was first published in 1989. You see what I mean?)

This was my bedroom, or part of it. It was on the top floor, and at night a beacon on the top of the newly-built Canary Wharf tower winked through my window There was a water boiler in the corner that heaved, breathed and gurgled. The room was maybe ten feet by ten, as big as the walk-in wardrobes in the hotel rooms I now occupy. But I loved it. I painted Molly Bloom’s last lines from Ulysses on the wall, in affirmation. It was, in the words of Shade The Changing Man #9, my pink heaven.

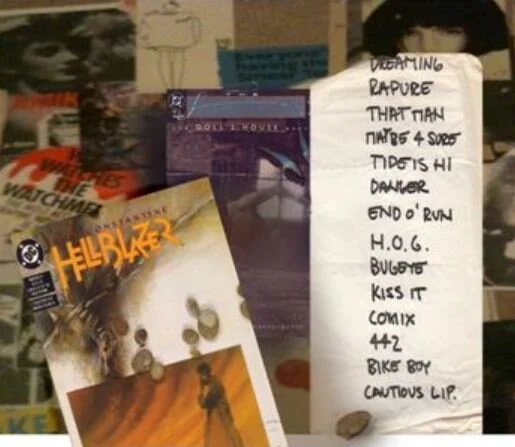

It was on that top floor that I and my co-editor Alice Constance Ballantyne put together Deviant Glam, a fanzine about comics and cosmetics that was informed by, steeped in, swayed by, and segued into the approach and aesthetic of the Vertigo comics of the period.

Yes, a fanzine. It was printed out, photocopied and sent out by post. This was a time of inbetweenness: between the days of analogue and the early internet, when mix tapes were starting to feel quaint and clumsy, but long before Napster. It was a time when cut and paste meant scissors and clue, not control-C and control-V. It was a time when a folder meant a cardboard wallet, a desktop was where you typed your letters on a clunky machine or wrote them by hand, when file was the first syllable in filofax, and wallpaper referred to the collage – tickets, snapshots, pin-ups and posters – you stuck above your bed to make your space your own, as I did with that line from Ulysses above my mirror.

And looking back, that’s another line from Ulysses: stolen from chapter 11, Sirens, with Miss Douce and Miss Kennedy in a Dublin bar.

‘She laughed:

—O wept! Aren’t men frightful idiots?

With sadness.’

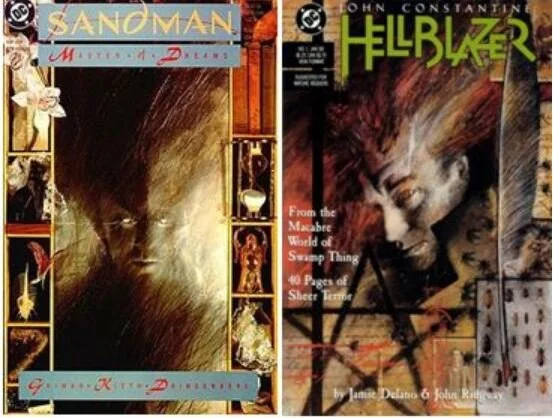

You wonder why every comic book and graphic novel cover by Dave McKean, Bill Sienkiewicz and their imitators between 89 and 95 was a mixture of postcards, pebbles, photographs and shells, with bits of lace laid over the top? Because our bedrooms looked like that. Because our diaries looked like that. It was a time of scraps, of bits and bobs. The Psychedelic Furs had a phrase for it, in their song Alice’s House (Mirror Moves album, 1984): ‘it’s a mess of souvenirs… there to remind you, telling the time.’

But Deviant Glam wasn’t just about comics (and not just about cosmetics). It was also – as the Fall put it, in their song Glam Racket, ‘entrenched in suede’. Brett Anderson’s indie band, dubbed ‘the last big thing’ by the music press, had released ‘The Drowners’ and ‘Metal Mickey’ in 1992. I bought all their singles, on vinyl, the day they appeared. It was a time of objects and physical artefacts. I was about Brett’s age. I became entrenched in Suede. The lyrics echoed and entered my diaries, which, I now admit, I often wrote when I was drunk.

‘I see you’re moving, see you’re moving

Moving in with her.

Pierce your right ear, pierce your heart, this skinny boy’s one of the girls.’

By coincidence, I’d bought my first Fall album (I Am Kurious Oranj, 1988) because of this frame from Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell’s superhero epic Zenith, where minor character Penny Moon wears their badge on her leather biker jacket for a moment in Prog 606, December 1988. The panel is barely the size of a postage stamp, but it stuck with me.

I probably bought a leather biker jacket because of Penny Moon, too.

Or maybe it was because of Zenith himself. Fiction had a way of blurring into fact, after a few drinks. And drinking had a way of blurring into sobriety. And the week had a way of blurring into weekend. There was a constant, low-level sense of party that segued into hangover and back to party, up and down, midnight to midnight. In May 1991, I borrowed the title of an REM song to describe the mood.

‘Carnival of Sorts’ was included on Dead Letter Office, REM’s compilation of B-sides and rarities, their rummage through the attic, their archiving of old files. I bought it to celebrate finishing my finals. (I’d gone out to buy the Cure’s album Mixed Up, but I got mixed up, and came home with REM instead).

All letters are dead now – antique museum pieces – but that was our means of communication not so long ago: not mails, but letters, with pen and paper. Straight boys sent handwritten letters to other straight boys, and added love and kisses at the end. I’ve kept them.

For a while, I looked a little like Zenith. That’s me reading Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell’s Sebastian O, near Comics Showcase in London, in 1993.

For another while, I looked a bit like Penny Moon. At another point, in another place, I looked a little like Kid Eternity, from the Grant Morrison and Duncan Fegredo reboot of 1991.

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and Head of the Film and Television Department at Kingston University, London. Professor Brooker’s work primarily studies popular cinema within its cultural context, situating it historically and in relation to surrounding forms such as literature, comic books, video games, television and journalism. In addition to the numerous essays and articles on film and fan culture that he has published, his books include Why Bowie Matters (2019), Forever Stardust: David Bowie across the Universe (2017), Star Wars (2009), Alice’s adventures: Lewis Carroll in popular culture (2004), Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans (2002), and the edited anthologies The Blade Runner Experience (2004) and The Audience Studies Reader (2003). He is also a leading academic expert on Batman and the author/editor of several books on the topic, including Batman Unmasked (2000) Hunting the Dark Knight (2012), Many More Lives of the Batman (2015).