On 'The Beano': Naughty National Icons and a History of Misbehavior (Part 1 of 3) by Dona Pursall

/What do Kofi Annan, Judy Blume and Ben E. King have in common?

They each celebrated their 80th birthdays in 2018. Born on the cusp of the Second World War, in the same year that nuclear fission was discovered and in which nylon and freeze dry coffee were introduced, they were children of another era. Superman and Lois Lane also turned 80 in 2018. This occasion was celebrated with an 80 page special edition of the 1000th issue of Action Comics and the publication of a curated collection of essays and re-prints Action Comics: 80 years of Superman The Deluxe Edition.

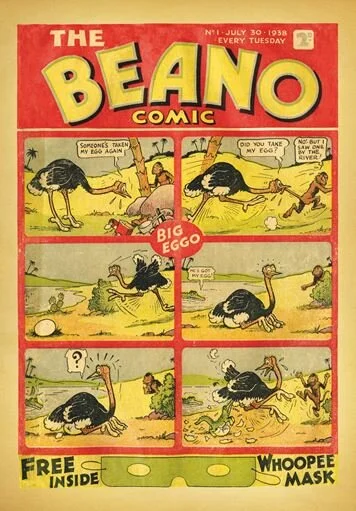

Front cover of the first edition of The Beano from 30th July 1938

British comic readers also celebrated an 80th in 2018, of not one character but of a whole comic, and importantly a children's comic. The ways that this special birthday was celebrated speaks loudly to the place it has in British culture and British hearts. In its honour, the V&A art museum in London hosted an exhibition entitled Beano: A Manual for Mischief, Stella McCartney produced a dedicated fashion collection for kids paying homage to the comic characters, the National Trust (a heritage charity for historic buildings and landscapes) held Beano inspired "mischief and mayhem" related events across the country, and the McManus, Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum, was renamed 'The McMenace' and hosted exhibits such as 'Minnie Lisa' by Duh Vinci, a Mona Lisa inspired portrait of Minnie the Minx, one of the comic’s most well-known naughty characters. The event became the most popular comics exhibition in UK history. What seems remarkable about these widespread appropriations of the comic's birthday celebrations is the incongruous relationship between these prestigious and well-respected institutions, and a comic for children where silliness, ridicule and misbehaviour are central tropes. It appears that despite its irreverent and mischievous nature, the comic has become a British institution in its own right.

‘Bean feast’ is an eighteenth century term referring to an annual formal dinner. The expression ‘beano’ originated from this and in its abbreviated form it became associated more informally with any party. As a title Beano drew from the positive associations of a festive occasion to inform the tone of the comic. It is published weekly as a gathering of fun-loving, original and energetic personalities who throw themselves wholeheartedly into celebrating life. They sometimes fail, sometimes succeed, they laugh at others and at themselves, they challenge and question, they play on the edge of the adult world, but always remain children. The diversity of characters has continually morphed throughout the 80 years of publication, reflecting real social changes which affect childhood experiences, but the feeling of a chaotic carnival has remained the foundation of the comic.

Excerpt of ‘Desperate Dan’ from Dandy No. 60 Jan 21st 1939

The market of comics for children was already richly populated both with imports and British story papers by the late 1930s. Text story magazines for children had been popular since before the turn of the century, offering serialized popular narratives of mystery and adventure. Comic strip stories were gradually included, though the magazines remained primarily textual, often drawing from literary genres. The Scottish publisher D C Thomson was already a major producer of British children's story papers when in 1937 they introduced a new humorous anthology, the Dandy comic which, unlike the existing story magazines, offered predominantly drawn comic strips, and included 'American style' speech balloons rather than captions.

The other way this comic differed from the existing offerings was through its main content of self-contained rather than serialised stories. It introduced completely original characters and reworked popular favourites. The first issue contained, for example, ‘Desperate Dan’, a ridiculously strong cowboy with an exaggerated square jaw and a reputation for eating giant cow pies (referring to pies made of cow meat, although the double entendre was probably intentional), and ‘Our Gang’, about a squad of unruly children based on the Hal Roach Rascals movies which had started as silent films released by M.G.M. in 1922. The publisher commissioned and employed artists and writers across the breadth of the country, many of whom who had never written for children before, to create significant and iconic characters who would become the 'stars' of the comic and thus capture the hearts and minds of the readers.

The success of the Dandy was followed with the launch of the Beano. It built on the most popular aspects of its big brother such as the non-consecutive strip style and the original and playful characters. The heart of the Beano comic, however, was the range and energy of the child characters presented, and their engagement with real-world children's issues.

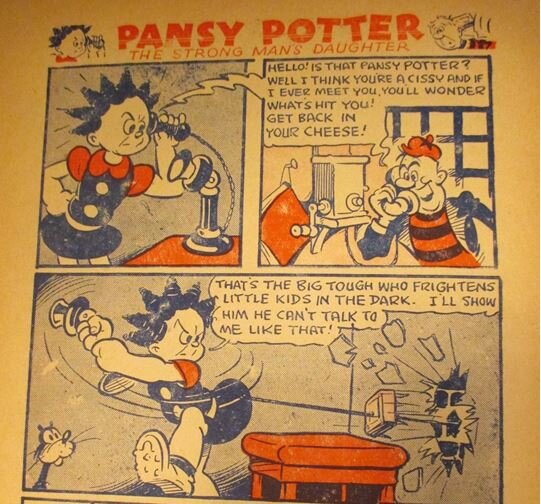

Excerpt of ‘Pansy Potter’ from The Beano annual 1940

The first editions introduced characters such as ‘Pansy Potter, the Strongman's Daughter’, a young girl with extraordinary muscles who is able to treat the great feats of human engineering, such as ships and aeroplanes, as though they are toys. ‘Wily Willie Winkie’ was an engineering genius able to challenge adult authority through his inventions. ‘Lord Snooty's’ aristocratic position enabled him to defend his pals from the harsh injustices of a socially divided society. A shared attitude of irreverence unites these strips, despite differences in age, ability and social status of the characters. The breadth of different types of character in the comics also offered readers variety enticing all children. It was launched as the first ever British children's comic for both boys and girls, a move which reacted against the very gendered magazines that had gone before, and responded to the anecdotal evidence that many girls already chose to read the 'boys' magazines rather than those marketed to them.

Disobedient and playful children were already a well-established trope in literature, film and comics by the 1930s in both the US and Europe. However, whilst humor in cinema tended towards inclusive, reconciling laughter to appeal to the widest possible audiences, and strip comics in newspapers often laughed at the separation between the child and the adult view on the world, the Beano comic introduced a new kind of anarchic comedy, of children laughing together against grown-ups.

Importantly though, the child characters not only challenged the expectations of behavior but also of looks. Beano children were not the neat, cutesy, stylized children that had become popular in the Victorian era and had continued to predominate as movie stars and marketing props such as Baby Marie Osborne and Shirley Temple. Beano children were clumsy, they had knobbly knees, spiky or disheveled hair and disproportionate limbs or heads. They were often illustrated with the inelegant, unbalanced stance of real children and their clothes were unfitting or patched. Changing labor and education laws had removed children from the factories and workplaces and required them to attend primary school, often reducing the already low income of the families and leaving children often alone in the world, on the street and unoccupied. Beanotown children were equally victim of the economic depression and food shortages as real British children were, their naughty behavior often being instigated by hunger and necessity. This was not the world of the privileged and the protected, but rather of the vulnerable underdog: a character 1930's child readers would have identified strongly with.

The Beano, No. 55 July 29th 1939

Dona Pursall is a PhD student of Cultural Studies, currently embraced within the COMICS project based at Ghent University, Belgium. Funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant, the project seeks to piece together an intercultural history of children in comics: https://www.comics.ugent.be/ Dona’s research explores children, childhood, imagination and culture within the history of humorous comics. She is specifically investigating the relationship between the British ‘funnies’ from the 1930’s to 1960’s and the experiences and development of child readers within the context of wider social unrest and political change.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is curated and edited by Dr William Proctor and Dr Julia Round