UK Underground Comix: Ar:Zak, the Birmingham Arts Lab, and Streetcomix #4 (3 of 3) by Maggie Gray

/The Arts Lab Press

The Lab’s press itself operated as a kind of print workshop, with a similar experimental, interdisciplinary outlook and close ties to local community activity and activism. At first, Lab event publicity and programmes were produced using table-top silk screen and an A4 offset litho printer loaned from a local cash-and-carry. In 1972 the Lab expanded into the downstairs area at Tower Street, which allowed for a dedicated silk screen space, used by Hudson, Bob Linney and Ken Meharg to produce vivid, innovative posters. A better equipped darkroom was also set up, permitting image scaling, halftone screening, colour separation and production of printing plates, which enabled the press (having acquired its own second-hand A4 offset machine) to print a range of publications in significant runs, good quality and colour, including poetry magazines, music scores and, of course, comics.

But as well as printing their own material, the Arts Lab Press also partly functioned as a print shop for the wider community, used by local activist and cultural groups, students unions and bands to produce newsletters, flyers and posters. It additionally printed alternative local papers like Street Press – part of a movement of, often radical, localised independent media that flourished in the 1970s. As Emerson put it, the Arts Lab Press took a “more sympathetic approach than a normal commercial printer” (personal communication 2018). It was therefore part of a larger nationwide network of co-operative printshops supporting the community arts and alternative press movements which shared the Lab’s commitment to enabling democratic participation in arts, and was listed in directories of community presses. The Lab also ran its own magazine stall selling local and/or alternative publications.

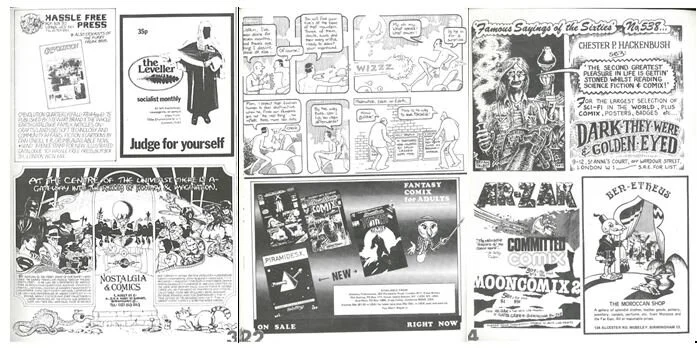

Figure 5. Adverts from Streetcomix #4, Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press, p. 33; p. 22; p. 4. © the artists

Ar:Zak publications shared the same distribution channels as the wider alternative press movement, carried by the PDC distribution co-op, as well as Hassle Free Press (later Knockabout) – set up by Tony and Carol Bennett to publish underground comix, but also operating as a distributor of various alternative papers and magazines. Ar:Zak comics therefore sold through the same network of headshops, radical bookshops, record stores and comic shops that supported alternative papers, and equally avoided the de facto censorship powers of commercial wholesalers like WH Smith. This interconnection of comics and the alternative press was evident in the fact that many alternative papers carried comic strips – with Emerson’s work, for example, appearing in Street Press, Grapevine, The Moseley Paper and Muther Grumble, amongst others. It’s also apparent in the adverts in Streetcomix #4 (Fig. 5), which include ads for various alternative publications like The Leveller, Co-Evolution Quarterly, Undercurrents and Fanatic, as well as Alchemy’s Brainstorm Comix and Pyramidesx, and comic book shops like London’s ‘Dark They Were and Golden Eyed’ and Bristol’s ‘Forever People’ along with Birmingham headshops.

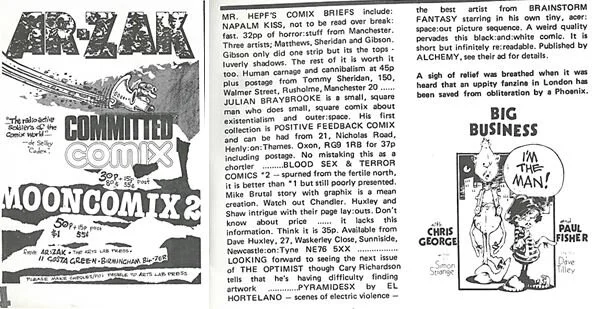

Figure 6. Mail order advert for Ar:Zak comics, Streetcomix #4, Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press, p. 4. Mr. Hepf’s Comix Briefs, Streetcomix #4, p. 49. © Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press

Ar:Zak

Similar ideas of making resources for independent media production democratically accessible, and supporting a wider movement in alternative publishing, framed Ar:Zak’s approach to comics. Emerson, who got a job at the Arts Lab Press in 1974 as a print operator, before taking over design and darkroom duties, had been self-publishing his Large Cow Comix series since 1972, using the print facilities at various ‘day jobs’ to run off small editions. The Arts Lab Press offered the perfect opportunity to print comics on a larger scale and in better quality, and so he teamed up with writer Paul Fisher (Streetcomix’ fictional editor Mr. Hepf), and Martin Reading (who had a background in theatre and came in to run the A4 offset litho), to form Ar:Zak. They were joined by cartoonists Suzy Varty (who co-founded Street Press), Chris Welch (previously involved with COzmic Comics and Nasty Tales) and Steve Berridge (‘a very young and angry punk’ by Emerson’s description), as well as Dave Hatton, who came in as a printer in 1976 to run a newly acquired A3 machine. Crucially, Ar:Zak didn’t just publish its own titles, like Streetcomix (first issued as a free insert in Street Poems magazine), or its members’ comics, like Emerson’s Zomix Comix and The Adventures of Mr Spoonbiscuit, but it also offered its services to others, printing David Noon’s Moon Comix and Mike Matthews’ Napalm Kiss, and thus supporting a wider UK alternative comics scene. Ar:Zak sold many such comics by mail order alongside its own titles, as advertised in Streetcomix #4, which also includes Mr. Hepf’s ‘Comix Briefs’ reviews of these and other alternative comics in its backend editorial pages (see Fig. 6).

Notably, many of these titles were - like Streetcomix - anthologies, featuring work by a range of creators, with varying levels of experience, in a diversity of styles and genres. As stated, Ar:Zak offered wider participants in the Lab opportunity to get involved with comics. Playwright and journalist David Edgar, for example, (a board member whose shows were performed at the Lab and who acted there himself), collaborated with illustrator Clifford Harper on an anti-fascist strip for Ar:Zak’s most politically acute anthology, Committed Comix, published in 1977 at a time when a broad grassroots anti-fascist movement was confronting the neo-Nazi National Front. Perhaps the most important Ar:Zak comic in terms of British comics history, which similarly engaged with key contemporary political movements, was Heroïne, the first UK (near enough)-all-female anthology, put together by Suzy Varty. Varty was involved in feminist activism and had links to the U.S. women’s comix movement - thus Heroïne brought British cartoonists together with American peers like Trina Robbins, and included work by members of the Lab’s Women’s Art Group with which Varty was involved. Published in 1978, Varty sold the comic at the national Women’s Liberation conference taking place in Birmingham that year.

Figure 7. KAK ’77 insert, Streetcomix #4. © Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press

As well as sustaining the alternative comics movement by enabling creators to print their work more affordably than via commercial printers, and in higher print runs and better quality than was possible through self-publishing, Ar:Zak also helped it cohere by organising two national meet-ups. The first of these ‘Konventions of Alternative Komiks’, which included panels, exhibitions, workshops and jams, was held at the Birmingham Arts Lab’s Tower Street site in 1976, with the second at London’s Air Gallery in 1977. As well as printing posters and special souvenir comics KAK Komix and KAK ’77, Ar:Zak reviewed these conventions in Streetcomix. Streetcomix #4 includes a report on the London event in the form of a pull-out printed on blue paper, which the reader is invited to cut up and fold into a smaller, digest-size publication of its own (Fig. 7). It features photographs, the results of several of the comics jams, and summarises the key issues discussed. These included the financial and distribution challenges faced by those working in the scene, but in particular centred on heated debates over sexism and how it could be challenged without leading to censorship. Varty had taken artists whose work Ar:Zak printed, like Mike Matthews, to task for the way they depicted women (Huxley 2001, p. 84), and the Streetcomix write-up insisted that consciousness of misogyny had to be developed in the movement: ‘it is both sexist and defeatist for a man to give up and say “I’m just a boring old sexist fart and I’ll always draw tits and bums”’. In response to later accusations that Ar:Zak itself was sexist, Streetcomix #6 was dedicated to the issue, featuring interviews with Ar:Zak, Robbins and Clay Geerdes on the subject, alongside strips from a range of Ar:Zak stalwarts.

Figure 8. Table of contents, Streetcomix #4, p. 3, © Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press

M. Steven Fox of Comixjoint (2013) has argued that Heroïne can be seen as a bridge between the earlier U.S. underground women’s comix movement that kicked off in the early 1970s, and the later wave of alternative comics by women creators. Streetcomix itself arguably acted in a similar way, open to diverse contributions from a broad range of creators, it featured work which drew on an established underground vernacular, but equally pushed in a number of new directions. As its table of contents attests (Fig. 8), Streetcomix #4 includes work from Geoff Rowley and Chris Welch (whose strips had appeared in underground titles like COzmic Comics’ Dope Fiend Funnies), as well a comic by J. C. Moody supposed to have been published by COzmic before they went bust. Alongside this more ‘first wave’ work, are contributions from cartoonists with closer connections to the alternative press, such as Emerson and Steve Bell, as well as artists like Jerzy Szostek and Andy Johnson who cut their teeth in the punkzine scene. Experimental strips from Birmingham creators like Robin Sendak rub shoulders with work from Ray Weiland and George Erling of the U.S. newave minicomics scene – a connection augmented by the fact Ar:Zak titles were included in a list of ‘British new wave minis’ compiled by David Noon for the 1981 Collectors' Guide to Newave Comix.

Streetcomix’ content was thus diverse, but it generally featured, as Ar:Zak themselves put it, creators ‘working in a less commercial vein that that usually associated with the comics medium’ (Streetcomix #2 1976, p. 3). This included work at the borders of the comics form, echoing the intermedial ethos of the wider Lab – in the case of Streetcomix #4, contributions from Szostek, Bell and Gary Hosty more akin to Hosty’s contribution (more illustrated prose, Johnson’s enigmatic fine-line illustrations, and even a Mr. Hepf editorial narrating a story of the characters Warbler and Yates who would appear in strips by Fisher and Welch in Streetcomix #5 and #6.

Figure 9. Hunt Emerson, ‘Large Cow Comix’, Streetcomix #4, Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press, p. 24; p. 31. © Hunt Emerson

The graphic design of Ar:Zak comics adopted the same innovative, experimental approach seen in the strips themselves, speaking to the fact it enabled cartoonists to also be involved as designers and printers. Typography is varied and bold, including playful typefaces made of human figures and prominent striped page numbers. Streetcomix #4 equally showcases an ambitious approach to printing, with Emerson’s ‘Large Cow Comix’ mobilising the rich colour possibilities offered by higher quality print reproduction (and better grade paper) to stunning effect, using colour to create evocative texture that adds to the silent strip’s enigmatic use of panel layout (Fig. 9). Having access to their own printing press and darkroom facilities enabled the Ar:Zak team to experiment with what the technology could do, including the machinery as a core part of the creative process. As Emerson recalls, ‘We were printing from photographic negative on to metal plates, and we used to work on the negatives, scratching out and painting ... We’d be getting effects in the drawings, collaging things with feathers and bits of rubbish’ (Emerson 2013). This is evident in Streetcomix #4, not only in comics like Blake and Sendak ‘s ‘Ice Age’, but in its broader design, with several of the strips overlaid on backgrounds that appear to be made up of some of this experimental photographed material (see Fig. 10). Fisher’s self-referential Mr. Hepf editorial similarly affirms the centrality of ownership of the means of production, and affective engagement with it, to what Ar:Zak was able to do with comics: ‘[Mr. Hepf] pulls a switch and the world is pushed aside by the rampant beat of the multilith. His eyes glaze over, as the pounding fills his veins’.

Figure 10. Pokkettz, Streetcomix #4, Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press, pp. 34-35. © Graham Higgins

For more on Ar:Zak and the Arts Lab Press, see Maggie Gray, ‘The Freedom of the Press: Comics, Labor and Value in the Birmingham Arts Lab’, in Thomas Giddens (ed.) Critical Directions in Comics Studies. University Press of Mississippi (forthcoming 2020).

Bibliography

Baetens, J. and Lefèvre, P. (2014) ‘The Work and its Surround’, in Miller, A. and Beaty, B. (eds) The French Comics Theory Reader. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 191–202.

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (1998) The Birmingham Arts Lab: The Phantom of Liberty. Birmingham: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

Emerson, H. (2013) ‘Back to the Lab: Hunt Emerson. Flatpack Festival: Projects.’ FlatPack Festival, March 24. Available at: https://flatpackfestival.org.uk/news/back-to-the-lab-hunt-emerson/

Estren, M. J. (1987) A History of Underground Comics. Berkeley, CA: Ronin Publishing.

Huxley, D. (2001) Nasty Tales, Sex, Drugs, Rock n’ Roll and Violence in the British Underground. Manchester: Critical Vision.

Long, P., Baig-Clifford, Y., and Shannon, R. (2013). ‘What We’re Trying to Do is Make Popular Politics: The Birmingham Film and Video Workshop.’ Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 33 (3), pp. 377-95.

Rosenkranz, P. (2002) The Underground Comix Revolution 1963–1975. Seattle: Fantagraphics.

Sabin, R. (1993) Adult Comics: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge.

- (1996) Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels. London: Phaidon.

Streetcomix #2 (1976) Birmingham: Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press,.

Streetcomix #4 (1977) Birmingham: Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press.

Streetcomix #5 (1978) Birmingham: Ar:Zak, The Arts Lab Press.

Steven Fox, M. (2013) ‘Heroïne’, Comixjoint. Available at: https://comixjoint.com/heroine.html

Wakefield, T. (2015) ‘Beau Brum: Remembering the Birmingham Arts Lab’. Sight and Sound, August 7. Available at: http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/beau-brum-remembering-birmingham-s-arts-lab

Maggie Gray lectures in Critical & Historical Studies at Kingston School of Art, Kingston University. Her latest book is Alan Moore, Out from the Underground: Cartooning, Performance and Dissent, Palgrave (2017). She is a member of the Comics & Performance Network and CoRH!, the Comics Research Hub. With Nick White and John Miers she co-runs Kingston School of Art Comic Club.