Promoting Tommy Steele through 1950s UK Comics (Part I of 2) by Joan Ormrod

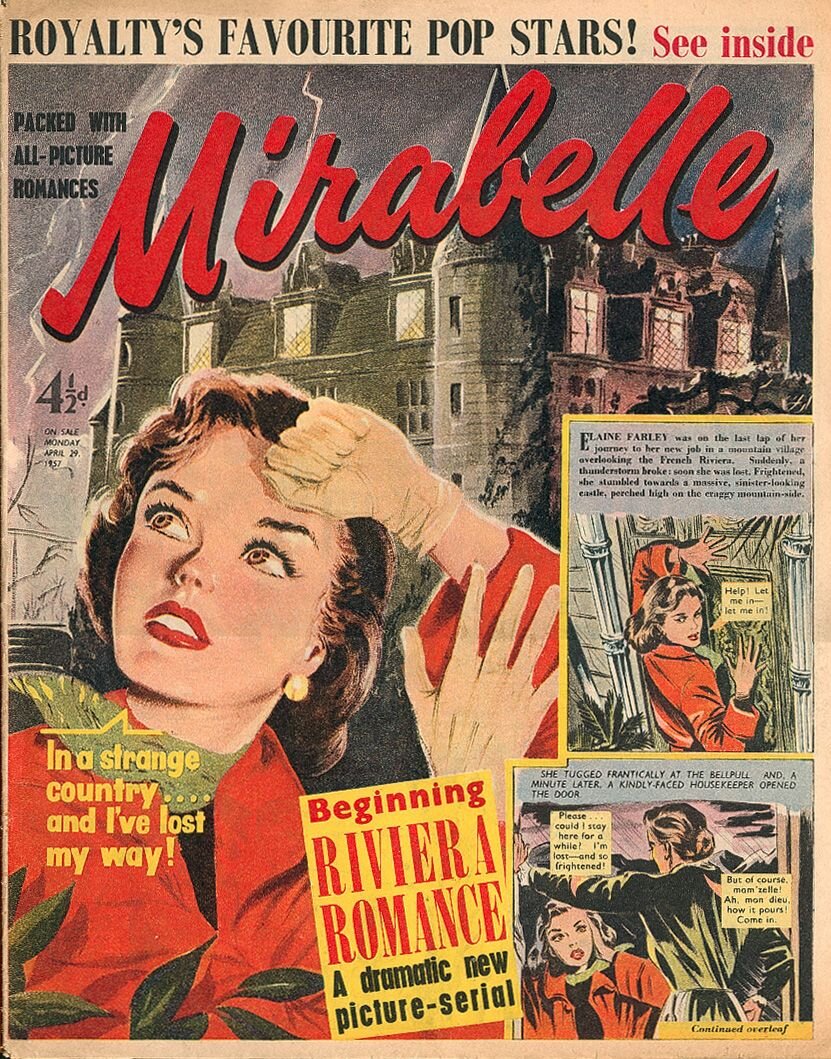

/On November 15th, 1955 Amalgamated Press (later Fleetway) published Marilyn, a comic aimed at the late teenage, early twenties female market. By the end of the 1950s, it became apparent that the comic had a younger readership of teenage girls, a newly identified emerging market. Teenagers in this era were identified as a market ripe for exploitation, as there was virtually full employment and they had no responsibilities. Consequently, teenagers had the money to pay for consumer goods, music, media and styles that differed from that of their parents. Marilyn was the first of several comics and magazine titles that identified and developed this new market. It was followed by Amalgamated Press’s Valentine (1957–1965) and Roxy (1958–1963), DC Thomson’s Romeo (1957–1974) and Cherie (1960–1963) and Mirabelle (1956–1978) and Marty (1960–1963 published by C. Arthur Pearson (later subsumed by Fleetway).

It was estimated that at least 40 percent of teenage girls read these comics. Their circulation varied from Valentine’s 407,000, Romeo’s 329,000, Marilyn’s 314,000 and Mirabelle’s 224,000. This readership may seem small compared with film and television audiences of 15 million in this era but if a comic had a turnover of 150,000, with rereading and swapping, this potentially translated into 750,000 readers.[i]

The comics came in either comic form (printed on cheap newsprint) or magazine form (printed on shiny paper with full colour covers). This depended on how the publisher’s presses were set up. However, all of them shared a similar format that hovered between comic and magazine with picture stories, text stories, articles (fashion, pop music), advice columns (beauty, pop music, lifestyle and relationships). At regular intervals they also contained free gifts. My interest in these publications is as much in the paratexts (the adverts, free gifts, the articles and advice columns) as the picture stories. All of these reflect what publishers perceived were teen girl interests such as consumerism, pop music and lifestyle. From their earliest publication these comics and magazines contained articles on pop music and this expanded throughout the 1950s into the 1960s. Comics could also provide what television and film could not—continuous accessibility. In this article I want to analyse the development of an emerging British pop music industry through pop star promotion.

Pop music was just one of several seductive American cultural imports aimed at teenagers. This started in the early 1950s with jazz and country music. The British media and cultural industries soon began to exploit American style and music. British pop stars were developed who emulated the major rock ‘n’ roll star of the late 1950s, Elvis Presley. While American stars, like Elvis Presley, were treated with awe, they remained largely out of reach. They had an advantage over the King – they were more accessible to the British teenager. British stars cultivated Presley’s look, music and snarl.

The first really big star was Tommy Steele. He is a good example how pop exploitation was already sophisticated and crossed various media. But it was comics where the teenage girl had ready access to the pop star through biographies, free gifts, stories and DIY. Through these channels she could imagine herself in a relationship with the pop star. The comics acted as a channel for her daydream and fantasy.

Comics and Rock ‘n’ Roll

In the mid-1950s rock and roll music arrived in Britain but, until the mid-1960s, it was difficult to access in the mass media. There were few television shows and films took forever to circulate on the distribution circle. The main ways teenage girls could access pop music was either Radio Luxembourg, playing records at home in their bedrooms or, if they were lucky and lived in a larger town, they might have a coffee bar. The bedroom was an important place where teenage girls could read comics, create a shrine to their pop idols, play records and discuss pop music and fashion with their friends. Comics were always there and they could be reread, loaned and borrowed.

Home grown British stars were incorporated into articles and advice columns in comics and they frequently mentioned how their visits to the publishing offices. In reading through the comics of the late 1950s I was struck by the amount of promotional stories and gifts devoted to Tommy Steele.

Tommy Steele the First Major British Pop Star

Tommy Steele's career in pop spanned 1956 to 1960. His career went from pop in the late 1950s to light entertainment from the early 1960s. Later he progressed to international success in Disney films and stage musicals. His career trajectory, from pop to light entertainment, was the anticipated career path of the teen star in the late 1950s up to the mid-1960s when music became recognised as a potential career path. By 1960, in an article about the record industry for Cherie #7 (November 12th, 1960), he admitted he had, “"risen slightly above [rock and roll], and I consider myself lucky that I have.”

Tommy Steele: Britain’s biggest pin-up & first major pop star

The official version of Tommy Steele's ascent to stardom is similar to that of other stars such as Cliff Richard, Marty Wilde and Terry Dene. He was discovered singing and playing in the 2i’s coffee bar by John Kennedy a freelance photographer. Kennedy eventually co-managed Steele with Larry Parnes. Steele’s good nature, charisma and youthful energy made up for his lack of singing ability in a market filled with adult or middle-aged stars. His first hits were cover versions of American songs and his appeal through the popular skiffle craze in the UK.

Within four months of his first hit record, “Rock with the Caveman,” he starred in a biopic, The Tommy Steele Story about his career to date in 1957. The film told of his unsuccessful career in the merchant navy and how he sacrificed it for his love of music. On being sacked by the navy, he began singing in a London café where he was discovered and became a star. This film was followed by The Duke Wore Jeans (1957) in which he played a working-class boy pretending to be a duke, and Tommy the Toreador (1958) in which a sailor, whose ship docks in Spain, becomes a toreador by accident.

The themes that were repeatedly used in comics stories about Steele often used his stint in the navy, working class origins, charm, kindness, humility and his guitar. Tommy Steele’s working-class background in Bermondsey acted as a means of making him less threatening representing him as a dutiful son. His stint in the merchant navy was used in films such as The Tommy Steele Story and Tommy the Toreador. In the latter, foreign settings such as Spain, then a glamorous destination in British tourism, provided an exotic locale for his international appeal.

Comics, Daydreaming and Tommy Steele

The promotion surrounding Tommy Steele included pinups, advice columns, free gifts and picture stories. Much of promotion was based on consumerism from raising awareness of his new records or films, or clothing ranges endorsed by Steele. In, “Dig This: The Tommy Steele Story,” Roxy #10, May 17th, 1958, Mary Verney Mellor described how Tommy and his brother, Colin Hicks who had also entered the pop music industry, spent their money on clothing. Despite their wealth, she stated that “Unlike the young Elvis Presley, Steele appears as an entirely non-threatening, asexual presence. Like Gracie Fields, he is closely identified with his working-class community, and is presented as a thoroughly decent lad who remains loyal to his roots.”

‘Tommy Talking’ showbiz advice column in Mirabelle, November 7th, 1959, p.5.

Stars also lent their names to advice columns Mirabelle’s showbusiness column of the early 1960s “Tommy Talking: The Lively column from our happy-go-lucky reporter” was purportedly written by Tommy Steele. In nearly all cases the columns were written by a staff writer, possibly the comic paying the star to use their name and image. In many cases, the star’s advice was promotional whether selling records, films, fashions or, like Alma Cogan, beauty information and fashion tips. Such promotion also developed the star brand and star as commodity.

Many articles, free gifts, stories and promotional materials promoted daydreaming and a fantasy of a relationship between Tommy Steele for his young audiences. Valentine #26, July 13th, 1957, Patti Morgan’s weekly fashion column, “Be Pretty and Smart” promoted a fashion range with matching his and hers clothing with prints of Tommy’s face and autographs. Accessories included guitar-buckled belts.

Star endorsement and fashion design in which the image and autograph inscribe the fan with his image. Patti Morgan, “Be Pretty and Smart” Valentine 26, July 13th, 1957, p.14.

The material components of comics such as free gifts and special purchases were used in promoting the star and in making him more accessible to the fan. A favoured free gift was transfers that could be ironed onto fan’s clothing or soft furnishings.

Transfers free gift. Marty (1961)

Fans could imagine themselves in a relationship in the picture stories or act it out. A free gift in the first issue of Romeo, 21st September, 1957, was the rock ‘n’ roll lucky wishing ring, “specially designed to fit any finger…Put the ring on the third finger of your right hand. Turn the ring until the initial you want to wish on is uppermost. Then wish your wish.” In this way the publisher directly addressed the fan.

Lucky Wishing Ring free gift – you put it on your right hand rather than left – the star was accessible but not too accessible. Romeo 1, 21st September, 1957 p.10.

ENDNOTES

[i] For girl comics reader practices in the 1950s see Mel Gibson (2016) Remembered Reading: Memory, Comics and Post-War Constructions of British Girlhood. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp.145-148.

Biography

Dr Joan Ormrod is a senior lecturer in the Department of Media at Manchester Metropolitan University. She specializes in teaching subcultures, comics, fantasy and girlhood. She has published widely on these topics and she has edited books on time travel, superheroes and adventure sports. Her monograph, Wonder Woman, the Female Body and Popular Culture will be published by Bloomsbury, February, 2020. Joan is the editor of Routledge’s Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics and she is on the organizing committee of the annual conference of Graphic Novels and Comics. She is currently researching girlhood and teenage comics in the UK 1955-1975.