On 'The Beano': Naughty National Icons and a History of Misbehavior (Part 3 of 3) by Dona Pursall

/By the time the first readers had grown up and become the parents of Beano readers, Beanotown characters had slightly fuller bellies and better clothes. By the 1950s the social context of the readers had changed, and so had the driving forces of the characters. Naughty behaviour was no longer a moralising reaction to adult’s poor values, but rather, in line with rising youth cultures of the time, a statement towards self-assertion and independence beyond the authority of the family unit. Pranking parents and dodging school were key motivations for the characters in this period, dads and teachers becoming the most common targets for mischief. This is typified by the introduction of new characters. Roger the Dodger, as the name suggests invests all of his energy into sidestepping any chores or responsibilities asked of him, and the Bash Street Kids dedicate themselves to learning as little as possible from and humiliating as often as possible their long suffering teacher. Rather than playing, as earlier strips, with the dynamics between adultishness and childishness, 1950s play positioned between looking respectfully to the past and looking rebelliously to the future.

‘Roger the Dodger,’ The Beano No. 807 January 4th 1958

The 1950's rise of the Teddy boy and girl culture marked both the rejection of post-war austerity and of earlier socialist models of community, and a move towards conspicuous consumption and the start of the neo-liberal teenage subculture. While the characters of the 30s and 40s, still confined by post-war rationing, were often happy to work for food, by the 50s economic rewards had become the norm. Beanotown children were no longer just mischievous, playing pranks for laughs, - they had become confrontational, determined to never grow into their parents and in response to their inflated rebelliousness, the punishments they received, from the very parents and teachers who were now the target of the humor, were stronger too; seeing children punished with a slipper or a cane became a common final image. This would perhaps suggest that the intended audience of these comics has moved away from the child, corporal punishment hardly seems humorous to victims. However, the joy for the child reader stems from the very violence of the punishment, which makes the risk so great, rather than from outright laughter. The characters, despite being aware of the possible consequences, continue to rebel; each week finding new, creative ways to challenge the status quo and sometimes, to the great relish of the readers, succeeding. The value in reading each week is found both in the creativity of the child characters, and the unpredictability of the outcome.

One such character appeared first in March 1951. Weirdly, in exactly the same week a character with exactly the same name also appeared in US newspapers, these were however two different, equally menacing, Dennis’. Dennis Michell is a freckled, blond, five year old who causes trouble mostly through his youthful innocence and curiosity for adult audiences and was drawn by Hank Ketcham as a single panel feature. Meanwhile, Beanotown’s Dennis had the tagline “world’s naughtiest boy” to his strips, and with distinctive black spiked hair and knobbly knees was a ten year old trouble-maker actively looking to create mischief and chaos wherever he went. His long-suffering ‘Dad’ was the most frequent victim to his antics, however anyone considered well-behaved or conforming was at risk. ‘Dennis the Menace’ has become a mascot for the Beano comic, continuing to react against rules and order to become the longest running strip in the comic.

Just as Beano characters were getting naughtier, the anti-comics movement became stronger and more vocal. Predominantly in the US but also in the UK concern was growing regarding the power of comics to corrupt young minds, and the fear that it would raise a generation of illiterate, disobedient young people increasingly led to strong moral campaigns by activists such as Fredrick Wertham. The debate was part of a wider contemporary controversy regarding ‘high’ and ‘low’ artistic culture. Comics for children received significant attention within this discourse as their readers were considered vulnerable. That a comic could be a social menace, and that adults were actively seeking to prevent children reading them inevitably led to the opposite reaction and in comics history the 1950s is regarded, rather ironically, as both the peak of the counter-comics movement and simultaneously, as the ‘Golden Age’ of comics.

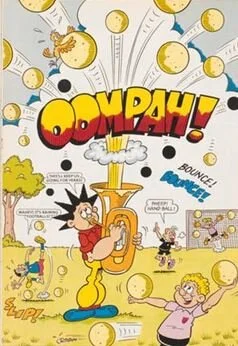

The 1950s children grew up and their children became the new Dennis the Menace Fan Club members. The childhood of the 1970s and 80s though had moved on rapidly. Conspicuous consumption, technology and fashion, music and TV offered new and exciting forms of entertainment to challenge the comics medium. The liberated free time of gangs of kids making their own entertainment on the streets had given way to organised sports and adult supervised activities. Energy children had previously invested in mischief and rebellion was now increasingly focused in team sports and computer games, steering play away from chaotic spontaneity and towards organised and purchasable activities. The reactionary social rebellion of the youth of the 50s and 60s had passed. Who you were was increasingly defined by the things that you had and wore; rather than what you did. The dynamic of conflict between parents, teachers and children was replaced by a return to the more slapstick and surreal mischievous behavior of the early Beano characters, however with many more resources with which to play tricks. While ‘Wily Willie Winkie’ had to make do with what he could find and make in the 1930s, the characters of the 1980s had water pistols, remote control cars, football boots and trampolines easily available to them. It is often these objects, things they have or take, which become the target of the jokes, either through their destruction or finding surprising, unusual or extreme uses for things for which they were never intended.

The new characters of this era reflected both the pace of change and developments in knowledge prevalent in this era. ‘Ball Boy’ for example only cares about football and is concerned with new kit, equipment and techniques for training, but he is plagued by the rather useless members in his team. Humor often stems from the gap between the characters' ambitions and the realities of what they can achieve, between ideas and their physical capabilities. This joyful nature of these strips lies in the characters persistence despite failure. Their disregard for the restricting limitations of reality is endearing and an important reminder to children to have big dreams. These children are no longer making fun of the constrains of social restrictions or authoritative adults, but rather of the void between the infinite possibilities presented to children that they can be or have anything they want, and the child as an erratic and unfinished being.

The Beano is a commercial product, and as such it has always strived to stay relevant and contemporary as times have changed. Inclusion of known or famous real people as comic characters has been a continuous technique used to achieve this, as well as storylines concerning real issues. They produced for example a special souvenir issue for the wedding of Meghan Markle and Prince Harry and for their 4000th issue in 2019 they introduced the new character Mandi and her Mobile, drawing attention to the issues children face with mobile phones.

The joy in these strips is connected with the journey characters take through the narratives, and that they remain fallible, incomplete children throughout. The reader is not guaranteed a laugh at the neat resolution of success, but because these characters are underdogs who work hard, who try and fail and grow. This style creates an honest unpredictability which is especially appealing to children because they identify with it. They accept that even though sometimes the strips end in catastrophe or punishment for the child character, the next edition has a fresh potentiality to it, a new chance.

Adult nostalgia towards their reading experiences of the Beano as a child is fascinating, as it is the resilience, the strength, the determination and rebellion of the characters that is remembered, rather than the uncertainty of success or failure at the end of the strips. There is an energy for action, risk taking, challenging norms and unsettling equilibriums, which adult memory associates with liberation, creativity and learning and not with obstreperous, obstinate children. It is this nostalgic memory that allows the V&A to proudly advocate their Manual for Mischief, as connected with strengthening and empowering children, not with creating a deviant population of young people. Naughtiness and misbehaviour in this context is playful, pervasive and a necessary part of child development.

This rose-tinted reminiscences inspired by the 80th birthday celebrations seems to imply that this comic about badly behaved, disruptive, unruly children represents something about British childhood and identity which is considered valuable and worthy and which has become idealised in connection specifically with the Beano. In continuing to genuinely view the world through the amazement of a child, seeing things for the very first time and not being immune to the wonder that this creates, the comic has remained joyful and innocent, and an important reminder that so many things adults take for granted can be questioned and disproved, or seen in a completely different way, when played with by an unencumbered and inquisitive child. Perhaps much of the nostalgia associated with reading these comics lies here, in how the Beano reminds us of something adults often forget. In looking through the prism of childhood we are able to see ourselves and the world around us in a fresher, freer, and more fun way.

Dona Pursall is a PhD student of Cultural Studies, currently embraced within the COMICS project based at Ghent University, Belgium. Funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant, the project seeks to piece together an intercultural history of children in comics: https://www.comics.ugent.be/ Dona’s research explores children, childhood, imagination and culture within the history of humorous comics. She is specifically investigating the relationship between the British ‘funnies’ from the 1930’s to 1960’s and the experiences and development of child readers within the context of wider social unrest and political change.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is curated and edited by Dr William Proctor and Dr Julia Round