On 'The Beano': Naughty National Icons and a History of Misbehavior (Part 2 of 3) by Dona Pursall

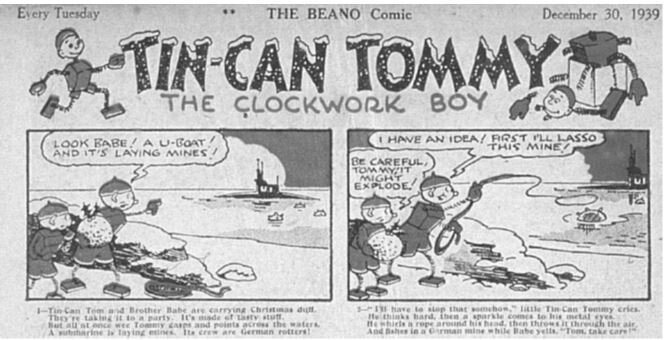

/‘Tin-Can Tommy’ from The Beano No. 75 December 30th 1939

The target audience for these comics has always consciously been children, editorial comments addressed them specifically, letters and jokes pages encouraged their participation and complicity. The tone, even in the early comics, constructed a pro-child attitude, often pitching their wit and their intelligence against flawed adult characters and systems. The ‘us and them’ approach to adulthood added to the popularity of these comics from inception. ‘Pranking’ adults who misuse their power and assume authority, and shaming bullies were particularly common tropes in these strips, as in the ‘Pansy Potter’ and ‘Wily Willie Winkie’ strips featured here. In directly challenging unjust adults, these characters demonstrate their own maturity. This became especially powerful during the Second World War when a predominance of absent fathers, and the mass disruption to families caused by urban evacuation, left many children effectively in unsupervised situations. In this context Pansy Potter single-handedly fighting against invading German tanks and submarines, Lord Snooty firing Hitler out of a cannon in a defiant act of justice, and Tin-Can Tommy taking on the Germans provided relevant, reassuring and inspiring role models for child readers as well as an important chance for laughter in very difficult times. These examples perhaps typify one of the greatest strengths of the Beano’s plot tropes, their adaptability.

Beano characters, as so many other comic strip stars, exist in a perpetual present. To use Umberto Eco’s term, the ‘oneitic climate’ is a world of hazy and mostly irrelevant pasts and futures and consequently of infinite possibilities. For the child characters this creates a fresh and naive approach to every experience, despite the longevity of many of these strips and the inevitable repetition of tropes allowing strips to respond directly to the world beyond the comic. During the Second World War for example, Hitler's authority became a natural ‘enemy’ for the characters. Jokes also often ridiculed characters demonstrating unpatriotic actions in the wartime context. Unfair or unjust behaviour such as stealing, arrogance or greed were common targets.

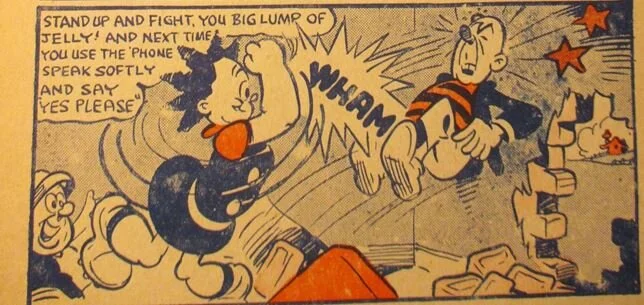

These strips often ended with a joke, a punchline or a pun. Although fantastical, these are not like fairy tales, narratives of character or situational transformation, they are rather joyful, playful moments, encouraging readers to look again at the everyday, the familiar with new wonder. Martin Barker has written comprehensively about how the characters serve the strips, that the notion of winners or losers in comic strip resolution is less important than the visual and linguistic ‘poetry’ of the strips’ composition. The elegance of the ‘Pansy Potter’ strip for example lies in the bullies belief that by using a phone to insult ‘Pansy’, he will be safe, and yet it is by following the very same telephone line that she is able to find and ‘educate’ him in phone etiquette. There is great joy in her total disregard of the chaos and destruction she has caused in the process of enforcing ‘good’ behaviour.

‘Pansy Potter’ from The Beano annual 1937

The social values of fairness, justice and respect remain important to the characters and the ethos of the comic. The playfulness however challenged naive expectation that children should be silent and well-behaved. In this regard these comics were genuine products of the late modernist movement, reacting against earlier Victorian restrictions, and instead following the trends in commercial and mainstream cultures of the day. They confronted the inadequacies of earlier philosophies about the idealised purity of children and instead embraced enlightened psychological and sociological knowledge about complex individual human experience.

Times change. What was considered mischievous behavior in 1940 cannot be the same as what is considered mischievous behavior today, and yet generations of adults unanimously agree that the comic is a poster child for childhood (mis)behavior. Although the exact nature of what is naughty or humorous has significantly changed in line with social morays, the anti-grown-up attitude, resisting seriousness, responsibility and most importantly rejecting or ridiculing tasks commanded of children by adults has remained a constant motif of Beano. Both intentionally disruptive misbehavior and chaos caused by misdemeanor seems to have remained equally popular throughout its history. The ‘enemy’ however has changed considerably through time, often in recognition of changing attitudes and social trends.

Each story in the comic interacts with a complex world. These are not narratives simplified to focus purely on the punchline, nor idealized to encourage aspirations of adventure and conquest as the story magazines had done before, but rather they engage with the complexities of everyday action and consequence in the child's journey of discovery.

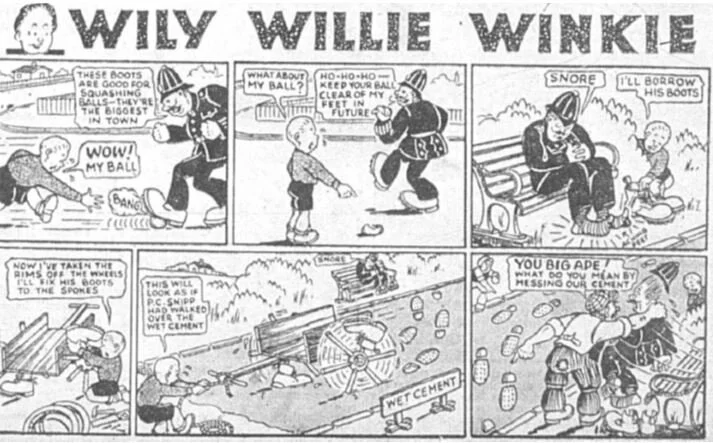

‘Wily Willie Winkie’ from The Beano No. 58 September 2nd 1939

In the ‘Wily Willie Winkie’ strip from 1939 the restoration of justice drives his inventiveness in the narrative. In the social context of the time, readers in the late 1930’s would enjoy the inversion of his position as powerless inferior to an adult of authority. The strip is about imagining how a child can make things better and what the consequences of that might be. As a comparison, the same motif of problem solving can be seen in the strip ‘Rubi’s Volatile Vacuum’ however in 2019 rebellion against abusive adults has been replaced by resistance to repetitive work and inadequate machinery. ‘Rubidium Von Screwtop’ is, like her father, an inventor. Just like ‘Willie’ she tackles challenges through innovation but often this causes trouble. Her lack of success seems appropriate however as she often tries to wrangle with the wonders of science, such as black holes, rather than just against disrespectful policemen.

Dona Pursall is a PhD student of Cultural Studies, currently embraced within the COMICS project based at Ghent University, Belgium. Funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant, the project seeks to piece together an intercultural history of children in comics: https://www.comics.ugent.be/ Dona’s research explores children, childhood, imagination and culture within the history of humorous comics. She is specifically investigating the relationship between the British ‘funnies’ from the 1930’s to 1960’s and the experiences and development of child readers within the context of wider social unrest and political change.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is curated and edited by Dr William Proctor and Dr Julia Round