'Crisis on Inbetween Earths' (2 of 2) by Will Brooker

/Grant Morrison and Richard Case later introduced a character named after another REM song, ‘Driver 8’, as one of Crazy Jane’s multiple personalities in Doom Patrol. The number on his or her cap was turned to one side, and the eight became infinity.

Lines from Ulysses escaped my diary and spread across my bedroom wall, above the mirror.

At the same time, James Joyce’s style was also shaping Grant Morrison’s prose, in Zenith.

I think it was a coincidence – that I was into Ulysses anyway, rather than that I read Joyce because of Zenith – but at this distance, it’s hard to be sure.

Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes I said yes I will Yes.

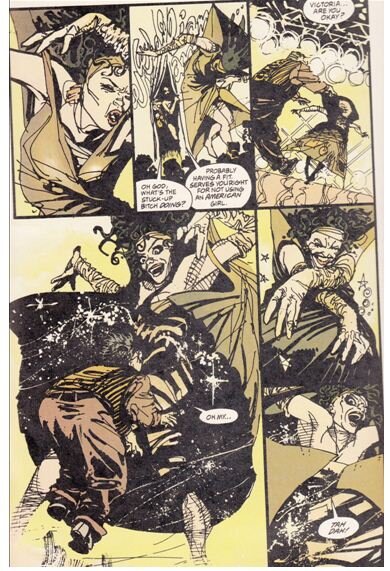

At around the same time, Peter Milligan (author of Shade the Changing Man) and Duncan Fegredo released a Vertigo miniseries simply called Enigma. Again, I was more taken with one of the minor characters: in this case, Victoria Yes. The Envelope Girl.

Victoria’s pages were the colour of manila. She could transport her victims across time and space, from one time to another place. That was her one power. I was entranced by her.

It was a time when the boundaries between producer and reader, author and fan blurred a little more than they do now. Grant Morrison published reviews alongside mine in Fantasy Advertiser magazine. I spoke to Alan Moore for hours at the theatrical adaptation of Halo Jones, and published our conversation as an interview in one of my earlier fanzines, Frisko (itself named after the Halo Jones disc jockey). I wrote comics, and without even meeting the artists who drew them – we communicated by letter, of course – I seemed also to appear in comics.

I became part of a small-press network, pre-Facebook, pre-MySpace, pre-Friendster. We wrote and drew comics, and circulated them by post.

My first script was called ‘Vertigo’. It wasn’t very good. I found my style writing stories about a man who, like Victoria Yes, had a girl somewhere inside him, an envelope waiting to be opened. And when she came out, he saw stars.

When I re-read those scripts now, I cringe a little – but perhaps not for the reasons you imagine. They are texts of their time: the year was 94, and I was raw. I didn’t have a better word than ‘transvestites’, and — because I was so young — I thought it was all about passing on the outside, not how you identified inside. These are stories from before LGBT was an acronym; before I had anything more than a sparse, inadequate vocabulary and a briefly-glimpsed community.

I didn’t have the words, at the time. The right word would come later.

But meanwhile, pre-Facebook, pre-MySpace, pre-Friendster, how did we all find each other? Through pamphlets, through fanzines, through comics: through postal addresses in the back pages of magazines.

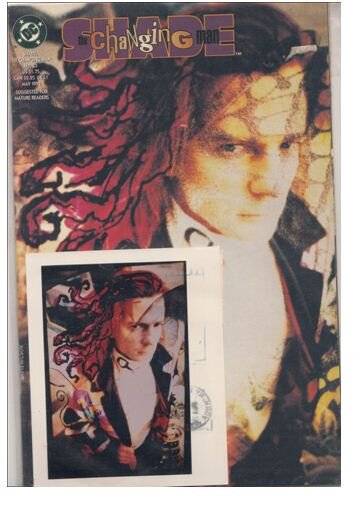

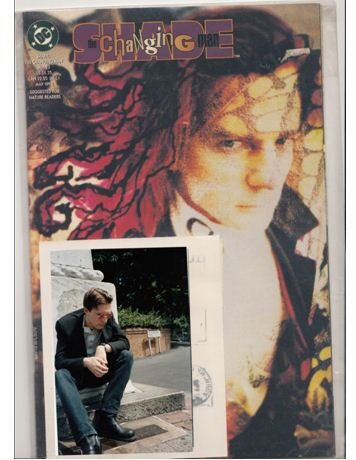

I wrote a letter to Shade The Changing Man every month, and it was printed every month: almost a regular column. And once, Shade wrote back to me. Artist Gavin Wilson sent me an original print of Shade, from his photoshoot for issue #23 (May 1992), ‘An Illusion of Real’.

So Shade was a real man, and we fans were a little like comic book characters. We were all so pretty, so seemingly-immortal. So young, so gone, as Brett Anderson put it in 1993. We’ll scare the skies with tiger’s eyes, oh yeah. (The opening lyrics to ‘So Young’ aren’t listed anywhere: Brett simply cries ‘Seeker! Star!’ a euphoric yell of yes.)

The Vertigo titles reflected us like a looking-glass. They showed us we could be a certain kind of superhero: shades, suede, leather, boots and buckles, broken parts and mosaic minds. Teams like Morrison’s Doom Patrol offered a gang of misfits we could all join.

I even performed in a Suede covers band. Funny, at the time I didn’t realise everyone in the house, everyone at the party, was gay.

But then, the boundaries were slippery. Brett Anderson claimed to be bisexual. Everyone I dated turned out to be bi. The binaries blurred. Shade the Changing Man woke up one morning as a woman, and went into a word-panic worthy of Molly Bloom: why man, woe man.

Milligan’s self-conscious wordplay – Joyce himself even featured in one episode of Shade – climaxed in a particularly slippery trick towards the end of Enigma.

‘Michael remembers the first time he stood naked in front of a strange girl…

Because that’s what he feels like now.

A strange girl.’

Like Shade, I was sharing a house with two or three other girls. I couldn’t always count them. That’s the kind of curious house it was: like Morrison’s sentient transvestite real estate from Doom Patrol, Danny-the-Street, things seemed to shift and move when you turned your back. I didn’t have the words, at the time, to describe the scene, the house, the carnival of sorts we were all part of – but later, I realised it had been starring me in the face all along, on the cover of a comic book.

Enigma, part 8, the final issue. A face stared straight out at the reader, with the caption ‘queer’.

Enigma is a remarkable comic: it seems obscure now, rarely-remembered, out of print. It’s astonishingly similar in its themes and approach to Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s later four-part series, Flex Mentallo (1996), but it’s not been examined or obsessed over to anything like the same extent.

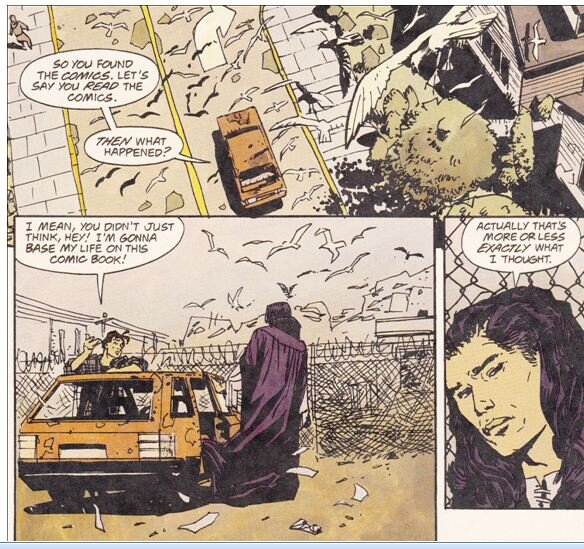

It tells the story of an ordinary man called Michael who meets a superhero – a gorgeous, larger-than-life superhero called The Enigma, who comes to life from the pages of a childhood comic book. But where Flex only implies the homoeroticism of the relationship between fan and icon, reader and character, civilian identity and costumed alter ego, Enigma faces it full-on.

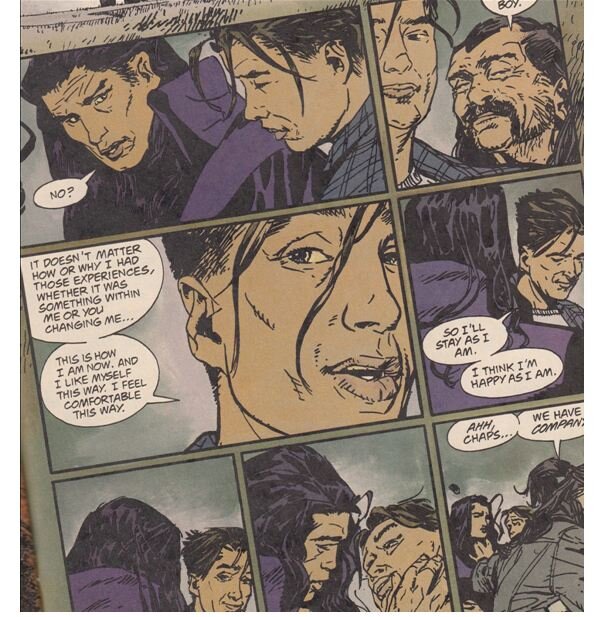

Enigma makes Michael gay. And then, in the last episode, offers to turn him back. And Michael says ‘NO.’ But it’s a no as positive as Molly’s final yes.

And as for me? I put the envelopes in the attic. I moved out, I moved house, I started a new life, I sold out.

I left everything behind and got a room in Cardiff, and began a PhD about Batman.

But that’s another story, for another time.

Will Brooker

November 2012

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and Head of the Film and Television Department at Kingston University, London. Professor Brooker’s work primarily studies popular cinema within its cultural context, situating it historically and in relation to surrounding forms such as literature, comic books, video games, television and journalism. In addition to the numerous essays and articles on film and fan culture that he has published, his books include Why Bowie Matters (2019), Forever Stardust: David Bowie across the Universe (2017), Star Wars (2009), Alice’s adventures: Lewis Carroll in popular culture (2004), Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans (2002), and the edited anthologies The Blade Runner Experience (2004) and The Audience Studies Reader (2003). He is also a leading academic expert on Batman and the author/editor of several books on the topic, including Batman Unmasked (2000) Hunting the Dark Knight (2012), Many More Lives of the Batman (2015).