More than Mere Ornament: Reclaiming 'Jane' (3 of 4) by Adam Twycross

/Daily Mirror 1934

In late 1934, with plunging sales at last spurring the board of directors into decisive action, Bartholomew was given full control of the Daily Mirror. His revolution was slow to take hold, the gradual pace necessitated by the board’s continuing nervousness concerning the scope and scale of Bartholomew’s emerging plans (Horrie 2003, p.52). In incremental steps, however, the entirety of the Daily Mirror was transformed, and by 1937 the revolution was complete (Smith 1975, p.64). The transformation had brought bigger, blacker headlines, a more concise and colloquial style of English, and a brasher and more irreverent tone overall. The importance and frequency of human interest stories had grown, and perhaps most obviously the use of images, and in particular comic strips, had rocketed. When Jane had first appeared in 1932 it had been one of four such strips, sharing the Mirror with Haselden’s regular cartoon, a juvenile humour strip called Tich, and Pip, Squeak and Wilfred. By 1937 Jane had been joined by Beelzebub Jones (1937), Belinda Blue-Eyes (1935), Buck Ryan (1937), Ruggles (1935), Terror Keep (1936), Gordon Fife- Solider of Fortune (1936), Popeye (1937), Connie (1937), Love Me Forever (1937), and Camille and Her Boss (1937).

Within the wider paper, a spirit of youthful irreverence had replaced the tired dogmatism of the Rothermere years, and it was in this context that erotic imagery, and particular images of female nudity, began to become a key feature of the Mirror’s address. Whilst this might suggest a straightforward repositioning away from the declining female audience that had barely sustained the Mirror during the 1920s, closer analysis suggests a more complex picture. Instead of representing a straightforward co-option of the female body for the gratification of a newly-male audience, the Mirror’s strategy instead was to frame the female body as an iconic signifier for the themes of energy, confidence and youthful irreverence that, as a paper, it increasingly sought to embody. These themes, and their visual projection, seem to have resonated with audiences of both sexes, and the paper continued to appeal to strongly to women (Smith, 1975, p.83), although admittedly it was a different type of woman than had been the case in the recent past. Hugh Cudlipp would later write that one of Bartholomew’s key new demographics was

“a section of citizens much neglected by newspapers of the time. Girls- working girls; hundreds of thousands of them, toiling over typewriters and ledgers and reading in many cases nothing more enlightening than Peg’s Paper” (Cudlipp 1953, p.87).

The synergy between audience and text that emerged during this period is typified by Blame it On the Moon, a piece of Mirror prose fiction written by Barbara Stanton, and which was published on August 2nd 1937.

Stanton 1937

Neatly epitomising many of the elements of the new Daily Mirror address, this short story detailed a summer romance enjoyed by Jean, a young woman holidaying alone at an English seaside resort. In one passage Jean is enthusiastic about displaying as much of her body as possible, noting with satisfaction that her shorts are shorter than those of another girl of a similar age, and she later goes for a naked moonlit bathe with a man she has only just met. “What would mummy have said if she’d seen us bathing without a stitch!” thinks Jean, “Still, there was no harm in it- and I don’t care what anybody says or thinks.”. Blame it on the Moon ran alongside an illustration of Jean and her paramour enjoying their moonlit encounter, with art supplied by Arthur Ferrier, who would later create Spotlight on Sally, a Jane competitor, for the News of the World..

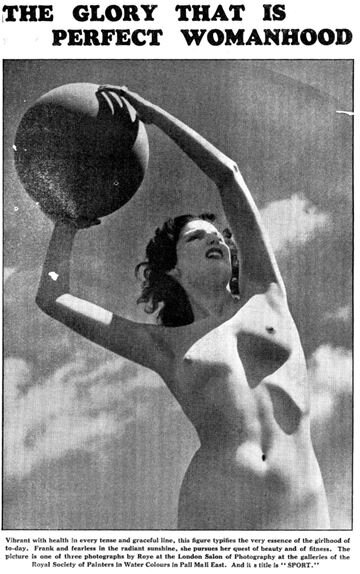

The Mirror’s use of female nudity as an iconic signifier of youth, vitality and the future potential of the nation was also in evidence in the paper’s photographic content. On 14th September 1937, for example, the Mirror ran a large photograph of an apparently naked young woman under the title “Perfect Womanhood”. The lighting conditions suggested that the photograph had been taken in brilliant sunshine, with a clear summer sky framing the subject as she readied herself to throw a beach ball to an unseen companion. The overall impression was one of youth, vitality, optimism and self-confidence, reinforced by the Mirror’s own accompanying commentary:

“vibrant with health in every tense and graceful line, this figure typifies the very essence of the girlhood of to-day”.

Daily Mirror 1937

It was in this context, two years before the outbreak of war, and more than six years before the D-Day landings, that nudity arrived in Jane. Like the wider Bartholomew revolution of which it was part, the pace of change was gradual, and at first nudity in Jane was suggested more than it was seen. The Jane strip of 9th July 1936, for example, depicted a furtive crowd gathering in a park in the hope of catching a glimpse of a naked Jane. later the same month another strip saw an excited crowd of men rush to Jane’s house under the erroneous impression that she would be welcoming them inside, in the nude.

Pett 1936a

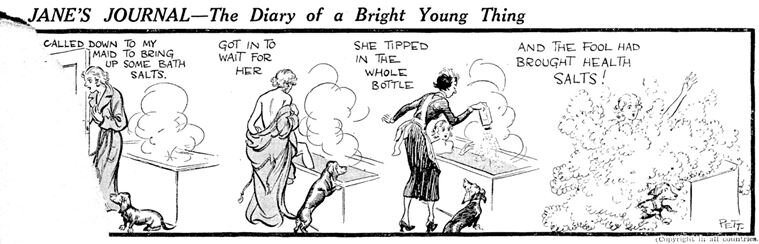

On 3rd December another strip used the potential for Jane’s nakedness as the central narrative conceit, when it appeared that she would be forced to hand the eiderdown with which she was covering herself to a courier. The closest that the strip came to an actual depiction of nudity during 1936 occurred on 11th November, when Jane was shown taking a bath. Only her upper back was visible, however, as she slipped out of a dressing gown, and once safely in the bath a profusion of bubbles hid her body from the neck down.

Pett 1936b

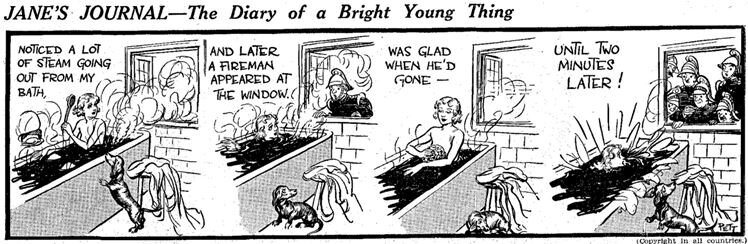

Four months later the strip was going just a little further; Jane was once again in the bath, but the bubbles had been dispensed with, and now only the positioning of her arm stopped Jane from appearing topless.

Pett 1937a

The spring and summer continued in a similar vein, when occasional trips to the beach were used as a pretext for Jane and her swimwear to either wholly or partially part company, although outright nudity was still avoided. By the late summer, however, the Mirror took the final step and Jane appeared entirely naked for the first time in August 1937.

Pett 1937b

Nor was this a one-off; having made the leap to outright nudity, numerous further examples appeared in the remaining pre-war period.

Pett 1937c

Adam Twycross is currently engaged in PhD research on the development and evolution of adult comics in Britain. Between 2012 and 2019 he was Programme Leader for the MA in 3D Computer Animation at Bournemouth University’s National Centre for Computer Animation, and has previously worked as a 3D modeller, with credits including the Xbox 360 title Disneyland Adventures and the Games Workshop graphic novel Macragge’s Honour. He is co-founder of BFX, the UK’s largest festival of animation, visual effects and games.