Celebrating 'Action': The Comic of the Streets (Part 2 of 3) by John Caro

/Hook Jaw took the point-of-view of the shark to tell its story. Subverting the traditional “boys own” Roy of the Rovers style sports strip of fair play, Death Game 1999 makes a ragtag collection of prison inmates the heroes, fighting against a corrupt system. Lefty Lampton and his notorious glass wielding “hooligan” girlfriend became the sympathetic leads – if the system in the form of an ineffectual referee won’t protect Lefty, they’ll look after themselves. Hellman, a World War II German tank commander is presented as an appealing anti-hero, operating on the Eastern Front to neatly side step any engagements with British troops. And Dredger made the conventional working-class oppo the protagonist, with the middle-class character assigned the sidekick role. Mills recalled:

We so often have something like Colonel Dan Dare and his working-class sidekick from Wigan, Digby. Isn’t it wonderful to reverse things? I think that was so good for the morale of ordinary kids reading this comic. I grew up reading so much stuff where it was Lord this or Duke that who was the hero. It’s so good to have a hero from the streets (Naughton, 2016, para. 21).

Perhaps on a surface level, Hook Jaw is not an obvious working-class hero but the character is certainly anti-authoritarian. The story represents nature’s fight back against greedy corporate humanity. It is a narrative device that Mills returned to several times within the pages of 2000AD. In Shako, trying to retrieve a secret government-created germ warfare chemical, the CIA foolishly takes on a man-eating polar bear (Shako, thinking the toxic capsule was food, accidentally ate it…). And in Flesh, matriarch of the tyrannosauruses and charmingly monikered Old One Eye leads a dinosaur revolution against the evil Trans-Time Corporation, a company that has travelled back in time to intensively farm dinosaurs for the ready-meals of the future. Cowboys, dinosaurs and giant spiders feeding on blood – how could the story fail? For readers the fake advertisements for dino burgers and steaks did for fast food what Willy Wonka did for chocolate sales.

From Action’s successor 2000AD. A mocked-up advertisement for Flesh – art by Kevin O'Neill

Hook Jaw, that merciless force of nature, would munch through cast members week after week. Making maximum use of the comic’s precious colour centre pages, the writers and artists would top each other for the inventiveness and gore of the kills. A personal favourite was a blinded diver swimming directly into the titular character's gaping jaws – “Hope this is the way…” Mills later celebrated the enthusiastic use of color:

John [Sanders] actually encouraged us in our excesses. I remember one episode of Hookjaw, which was beautifully painted in watercolours. I recall John getting a paintbrush with red paint on it and saying, More blood, More blood! (Naughton, 2016, para. 33).

Yes, Hook Jaw killed indiscriminately but he appeared to save his more spectacular kills for particular types of character – for example, Red McNally, the cruel despot that runs an oil rig in the Caribbean. In the climax to the story, Hook Jaw makes a meal of his nemesis, not so much eating him as, well, bursting him. See for yourself…

McNally meets his end in Hook Jaw – story by Pat Mills and Ken Armstrong, art by Roman Sola.

In the sequel, Dr Gelder, the cruel capitalist owner of Paradise Island, meets his end not at the teeth of Hook Jaw, but speared by a member of the indigenous tribe he has exploited. In a story that features some toe-curling racial politics, it is at least of some solace that the colonialist is killed by the colonised. What is also of note is the fate of returning hero, Rick Mason. In a grisly fate reminiscent of EC Horror Comics, he is unceremoniously “de-bodified”, his decapitated head replete with lolling tongue washing up on shore. A particularly gruesome end which, long before Game of Thrones (Benioff and Weiss, 2011-2019), established that no character was safe. Mason had to die. Action wasn’t about traditional square jawed heroes. Hook Jaw was the only star of the story.

Another important part of Action’s rebellious working-class identity and appeal to its readership was its regular features. In the best tradition of the “Hello kiddies” Crypt Keeper, Action had a host – “Action Man” Steve. Except this was a host who wrote about his trips to the pub and his experiences performing dangerous stunts (although one would hope not necessarily in that order). Even the name Action Man would have been understood by readers as a reference to the then popular Palitoy doll (better known as GI Joe in North American markets).

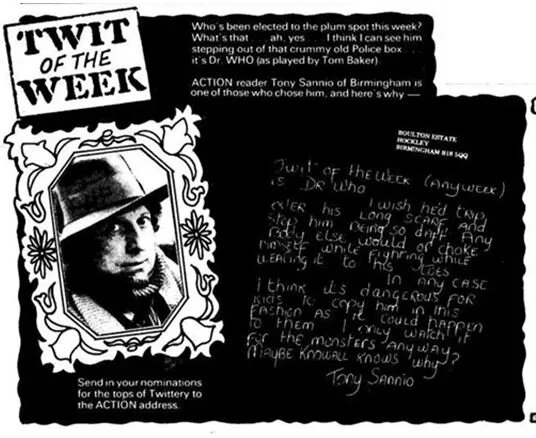

Mills also wanted feature material, which he would lay out in a style that aped The Sun. Its concerns were both working-class (speedway, wrestling) and anti-establishment (there was a regular Twit of the Week slot which featured, among others, University Challenge presenter Bamber Gascoigne). Mills enlisted Steve MacManus, who would go on to be one of 2000AD’s most successful editors, but was then working as a sub-editor on Battle, to help out. He became Action Man, the game-for-a-laugh face of the comic who would be set challenges by the readers on a weekly basis. (Naughton, 2016, para. 27)

An example of Action Man's weekly column

Twit of the Week from 24th April 1976 - Doctor Who

In an era when perhaps the “establishment” was easier to define, Twit of Week exemplifies the subversive and irreverent nature of the comic – celebrities were not admired, they were mocked. Readers delighted in sending-in their nominations and justifications. The list included big hitters such as Nicholas Parsons, The Bay City Rollers, Donny Osmond, Lee Majors and Bruce Forsyth. Again, given Action’s fondness for adapting inspirational source material, it is of note that starting in 1974, Larry Flynt’s Hustler featured a regular “Asshole of the Month” nomination.

Another direct lift used by Action to reach out to its followers was the Mad, Mad Money Man. This was based on an old newspaper promotional campaign where figures such as Lobby Lud and Chalkie White would advertise a publication by giving away money to readers in the know.

Chalkie White comes from a distinguished tradition of mystery men, a British summer institution that began between the wars with the News Chronicle's Lobby Lud and was celebrated after a fashion in Graham Greene's Brighton Rock. Each day a picture of Chalkie's eyes appears in the Daily Mirror and each day the Great British holidaymaker memorises them, together with the line he must say to claim the £50 prize. It is usually some such sentence as "To my delight, it's Chalkie White". (Rusbridger, 2005, para. 4).

Steve MacManus later recounted his experience on the Action “outreach” activity, accompanying Money Man and former Valiant editor, Stewart Wales on a visit to Brighton.

On arrival at the train station we disembarked and made our way to The Lanes, where we expected to be challenged (or razored) at any moment. But, despite a swarm of kids carrying that week’s copy of Action evidently looking for the Mad Money Man, not one of them appeared to recognise Stewart. Eventually the penny dropped for one youth and he challenged Stewart successfully. The boy looked shellshocked when he was instantly handed a crisp £5 note and as we departed he remained rooted to the spot, staring blankly at the small fortune in his hands (2016, p. 57).

John Caro is currently Assistant Head for the School of Film, Media and Communication at the University of Portsmouth. A graduate of Northumbria University’s Media Production programme, in 2001 he completed a Film and Video Master’s Degree at Toronto’s York University, supported by a Commonwealth Scholarship. He has directed and produced numerous short films, screening his work at Raindance and the International Tel-Aviv Film Festival. From 1983 to 1987 he was a set decorator at Pinewood Studios, working on such films as Aliens and Full Metal Jacket. More recently, he contributed reviews to the Directory of World Cinema: American Hollywood Volumes 1 & 2 (Intellect, 2011 & 2015), and his essay on the re-imagined Battlestar Galatica series, co-authored with Dylan Pank, appeared in Channeling the Future (Scarecrow, 2009). Of late he has rediscovered his love of British comics and re-joined the ranks of Squaxx dek Thargo.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is curated and edited by William Proctor & Julia Round.