Remembering UK Comics: An Interview with Martin Barker (Part 1 of 2)

/Introduction: How do you know what you know?

William Proctor

I hope everyone had an opportunity to take a breather over the Christmas holidays, and have now woken up in 2020 all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed!

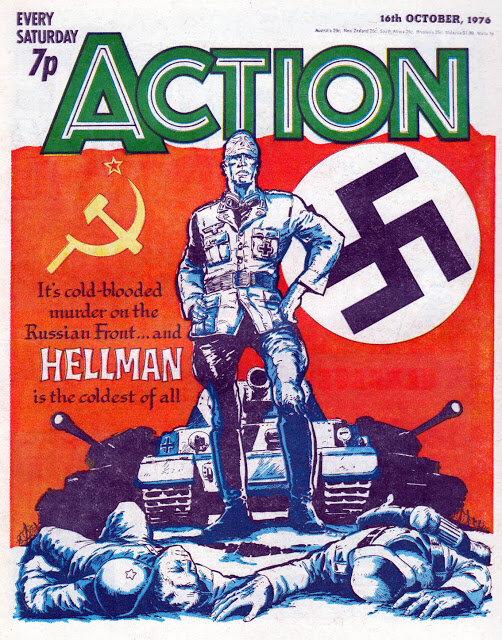

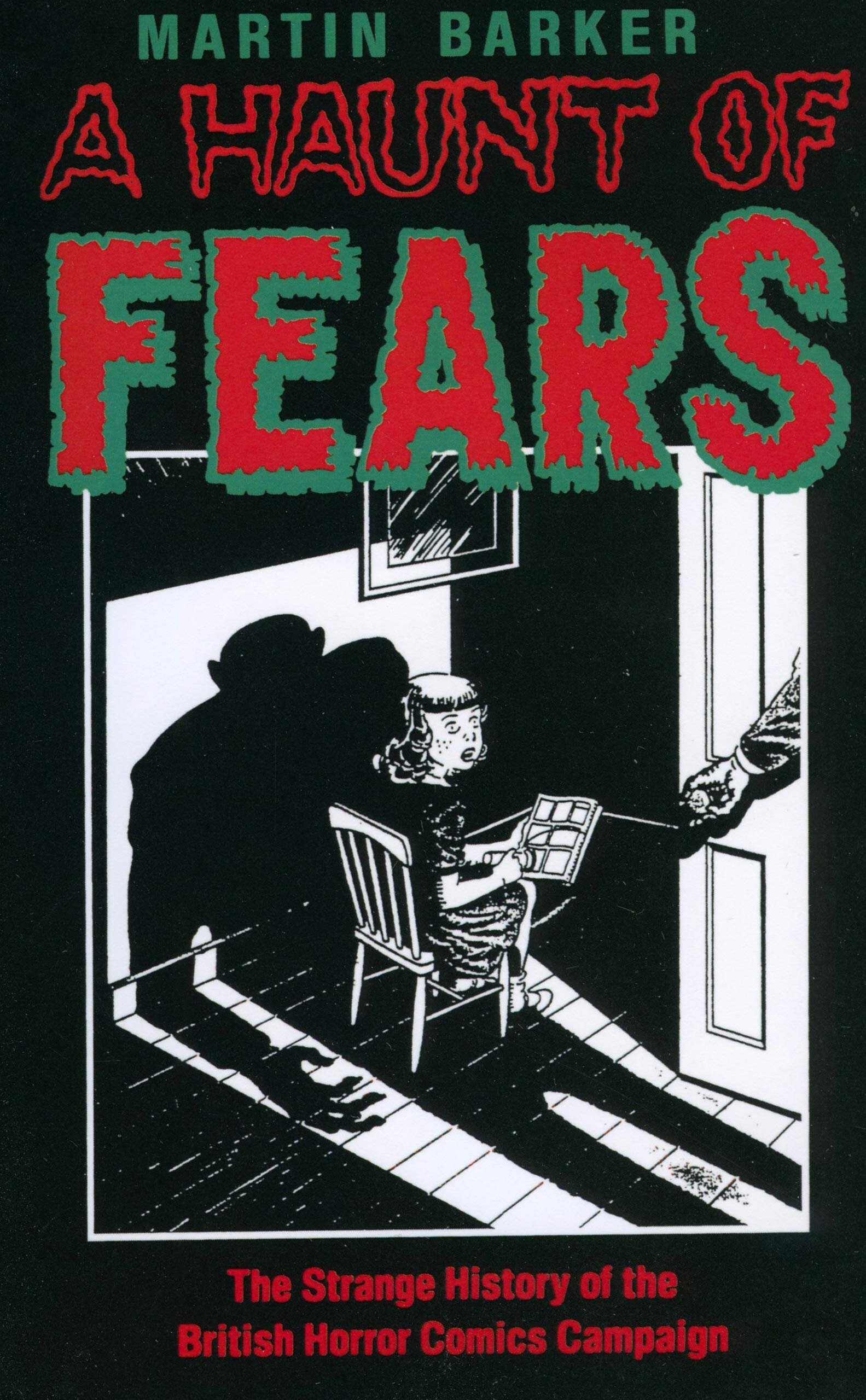

We return to the ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series this week with a special interview with Professor Martin Barker, who I’m sure many comic studies scholars know from A Haunt of Fear: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign (Pluto Press, 1984) ,Comics: Ideology Power and the Critics (Manchester University Press, 1989), and Action: The Story of a Violent Comic, (1990), all of which provide exceptional, insightful studies of the medium, its receptions, and its audiences.

I first became aware of Martin’s work as an undergraduate at Sunderland University in the North-East of England, courtesy of Professor Clarissa Smith (who was incidentally supervised by Barker for her PhD, which became the excellent monograph One for the Girls! The Pleasures and Practices of Reading Woman’s Porn, 2007). Martin’s work upended everything I thought I knew about audiences, about media effects, about academic studies that were built on less than solid grounds for the vaunted claims that were being made. More often than not, Martin’s work—and indeed, Martin himself—challenged me to maintain a vigilant watch on my assumptions and prejudices, which of course we all have whether we care to admit it or not. One of the questions Martin once asked me over dinner one evening actively threw me into a philosophical tailspin for days, a seemingly innocuous question that I believe has served me well ever since. I don’t recall what we were discussing, but the question is there, burned on my brain for all-time, a scholarly scar that I’m especially proud of.

How do you know what you know?

I didn’t know how to answer that at all! I know what I know because I know it? That’s a tautology if ever there was one!

I believe that Martin was asking a simple question about the epistemological foundations of whatever argument or position I was espousing. This kind of query underscores a lot of Martin’s work over the past four decades or so (at least in my reading). I want to expound further as I think it’s an important point that Martin was making.

How do you know what you know?

“Erm, I’ve read books and stuff”?

That just won’t cut it with Martin.

If we reframe Martin’s question, it becomes even simpler:

What evidence do you have that supports your claims?

Let me offer an example from Martin’s work that should challenge and provoke our common-sense beliefs.

In one article, Martin diligently pursues the thorny concept of ‘identification’, a concept that has oftentimes been mobilized by American Behavioral ‘Scientists’ to establish, and thus prove, that casual links exist between fictional media and the behavior of its audiences. Many readers probably understand this model interchangeably as the ‘magic bullet,’ or ‘hypodermic needle’ theory, terms which can be understood as part of the so-called media effects tradition. In very basic terms, the media effects tradition treats audiences as little more than empty containers to be filled up by insidious and sinister ‘messages’ transmitted by ‘the media’ (whether TV, film, comics, and what have you).

In many ways, ‘media effects’ has long been empirically debunked for decades in academic circles, or I should say, in some academic circles. It is perhaps surprising that the concept lives on, and remains a powerful way of (mis)understanding the way in which media forms ‘do stuff’ to us, be that psychologically, behaviorally, and/ or emotionally. Many embracers of ‘media effects’ have found it difficult to provide solid foundations for their claims, primarily because the tradition is akin to a house of cards trying to maintain its structure in a hurricane. Yet it persists.

In relation to ‘identification’, Barker writes:

“The concept of ‘identification’ remains a commonly-called upon resource for considering how media audiences might be influenced into taking up moral and cultural positions. Yet very little empirical evidence exists to support its claims; and recent critical conceptual work has undermined many constituent parts of it […] If audiences ‘identify’ with particular media characters, they come to ‘take part’ in the story to a depth where they become open to its ‘values’, or ‘messages’. The concept belongs to a domain of thought concerned with audiences’ vulnerability […] the concept was at work, albeit without the particular word to express it, as early as the 1850s. Its component parts were at work within, for example, 19th-century scares about the influence of Penny Dreadfuls. This is important, for it suggest that we have here a concept that benefits by remaining unclear “(Barker’s italics, 353-54).

At the heart of Barker’s critique here is that ‘very little empirical evidence exists to support its claims’.

How many times have we been confronted with claims about media ‘messages’ anchored to the concept of ‘identification’? Unfortunately, it is so much a part of accepted wisdom and common-sense that we don’t tend to query these claims, and some academics continue to mobilize their ‘evidence’ in similar ways. The question, then, ‘how do you know what you know?’, becomes less neutral than it seems at first. It is essentially a question about epistemology, about the empirical foundations that support and do not support scholarly claims in this arena. How many times have you read academic studies that use terms like ‘messages’ without solid foundations provided by empirical data? How have these ideas and concepts been tested?

How do you know what you know?

I have been very fortunate to have had many opportunities to speak with Martin about these kinds of issues, some of which I admit had never crossed my mind during my PhD years. When I was thinking about conducting a large-scale audience project based around the first Star Wars film under Disney’s control, Martin kindly invited me to his home in Aberystwyth, Wales, to talk through the challenges that he faced, and the methodology he created, on various audience studies: from the Crash controversy of the 1990s and the Sylvester Stallone/ Judge Dredd film to the Lord of the Rings and World Hobbit projects. Martin is very experienced at working with ‘big’ data sets, a ‘richly structured combination of data and discourses’ of a size not that common in academia. Respectively, the Lord of the Rings study captured almost 25,000 responses, while the World Hobbit project garnered 36,109.

One of the things we discussed at Martin’s home was psychoanalysis. I don’t think Martin would mind if I said that he has been openly critical of psychoanalytic approaches to culture. Indeed, in the introduction to From Antz to Titanic: Reinventing Film Analysis (2000), Martin admits that ‘one of the main motives for writing this book is my dislike of psychoanalytic modes of film analysis’, partly because he has ‘sympathy for students’ frequent sense that to read the stuff is to take forced marches through jungles of jargon, behind whose every frond lurks a phallic snake, biting, accusing’ […] But mainly, I reject psychoanalytic accounts because their findings resolutely refuse any kind of empirical verification (13).

How do you know what you know?

I explained to Martin that psychoanalysis might well be little more than an intellectual parlor game, replete with assumptions and imputations, but its users have the critical upper hand in a sense. Which is to say, psychoanalysts rely on the ‘subconscious’ as a ‘get out of jail free’ card. One doesn’t need empirical evidence if we’re talking about the subconscious—no-one has access to the subconscious activities of their own, never mind audiences.

Martin’s response was brief yet profoundly impactful on my thinking, and has remained so ever since

“I don’t believe in the subconscious.”

Imagine that! What if everything we think we know about the human mind, and the subconscious is not supported by empirical evidence (it isn’t)? Yet like ‘identification,’ perhaps even more so, we use the idea of the subconscious in everyday conversations. It is common-sense, naturally, but it could be nonsense too! Indeed, even the psychoanalytic community have admitted that it’s wholly theoretical and unfalsifiable (and as a consequence, unjustifiable); that is, it can neither be proved or disproved.

To this, Martin recommended a book by Valentin Voloshinov called Freudianism: A Marxist Critique, a heady text that I wouldn’t recommend for bedside reading. I openly admit that I may not have yet grasped the finer granularities of Voloshinov’s argument—he is one of those theorists that are intensely tough to grasp, in my view— but it is worth checking out all the same.

(I should say that Martin wasn’t saying he’s right and everyone else is wrong. I often view Martin as someone who relishes chucking spanners into the works as a way to complicate and challenge what we believe to be ‘true.’)

That afternoon, we chatted more about this, and other topics, and I strongly believe that the many discussions we have had over the years has made me a stronger scholar. In many ways, my engagement with the concept of what Bridget Kies and I describe as ‘toxic fan practices’ came about precisely because of the imputations and assumptions made by journalists (and scholars). ‘Why are (some) Star Wars fans so toxic?’ ‘Fandom is so toxic right now.’ ‘The alt-right claims credit for the Last Jedi backlash’.

How do these commentators know what they know?

Who knows!

I’d like to thank Martin for his work, his generosity, his friendship, and for posing that question while we ate dinner one gloomy night in Newcastle. I am both fortunate and very grateful to have had the opportunity to discuss and debate many topics over the years, discussions that have had such a massive influence and impact on my life in academia thus far.

Oh, and Martin kindly passed on his collection of Action to me, with only one rule: ‘enjoy them.’ And I have,. and will continue to do so.

In the interview that follows, Martin and I discuss his career, with a particular focus on UK comics and those early, seminal studies that anyone interested in not just comics, but audiences, ideology, media effects, politics, etcetera. should most certainly check out. Be careful though: you may need to check your assumptions and prejudices at the door. But that’s not a bad thing. Not at all.

William Proctor

———————-

Q: You’ve done a lot of work on censorship and debunking media effects arguments. Can you say a bit about how the British horror comics campaign fits into bigger debates and trends in censorship practice? What can it teach us?

Just a quick word at the beginning about how and when I did this research. It was in fact my first foray not just into comics research, but also historical and empirical research – and I learnt as I went (it was the early 1980s). That was both lucky and unlucky. Lucky, in that my naivety let me trip over things that might otherwise have remained hidden (particularly when I interviewed surviving campaigners); unlucky, in that it took me quite a few years to learn how to fill in gaps in the historical knowledge (in particular when I finally got round to looking at British Government Cabinet Papers). Unlucky, in that one organisation destroyed key materials just as I was approaching them about the period. Lucky, in that they felt really guilty about this, and so made me a present of a surviving piece of materials which gave me some key insights!

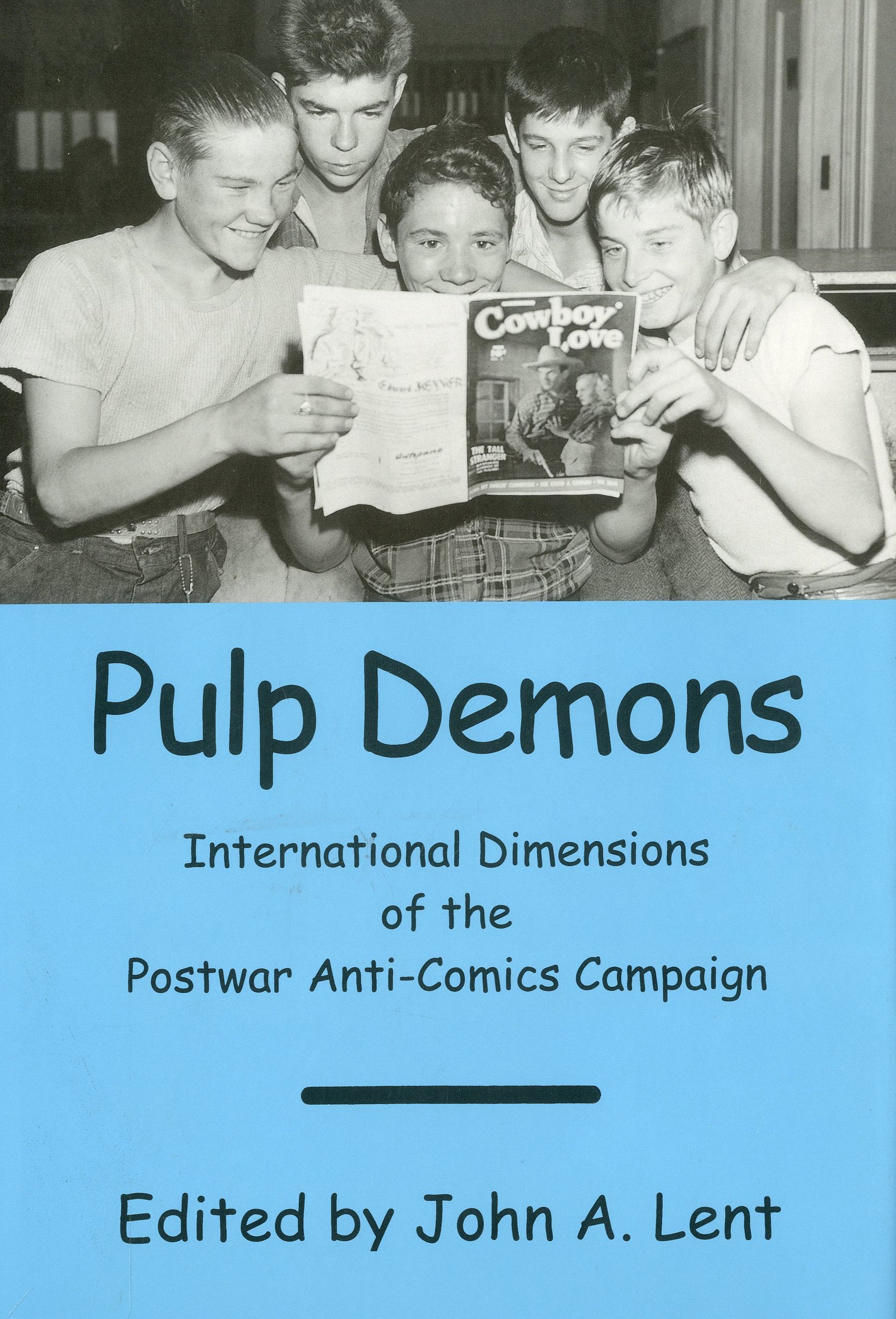

What I would now say is this. The anti-crime/horror comics campaigns were simply exceptional, in the sheer number of countries involved (more than 20). But, as emerges very clearly from John Lent’s (1999) Pulp Demons, there were a whole series of local drivers which meant that the local campaigns were in some ways distinctive. And there is no question but that the local colouration of the British campaign owed a great deal to the role played by the British Communist Party, which staffed and financed and motivated the campaign as part of its attempt to attack ‘Americanisation’ of culture. I would say that revealing the part played by the CP, via their various publications on the topic, was a key contribution. I was able to show in particular that there was a decisive shift in their rhetorics in 1953, from talking of ‘American culture vs British heritage’, to ‘horror vs children’ – because it depoliticised the public image of their campaign, and helped to ‘hide’ their involvement. But the price – that they ended up attacking some of the few elements of anti-McCarthyism coming out of America in this period, in the EC Comics – is a horrible irony. These were the EC Comics, which used melodramatic Grand Guignol story-lines to take various strands of extreme American conservatism, nationalism and racism to task.

So, to me the lessons of this are that (a) we cannot trust the rhetorics used by campaigners – they regularly conceal their motives behind a front of words which make them as publicly acceptable as possible. ‘Protecting children’ – who could possibly object to that? I found precisely the same with the later ‘video nasties’ campaign, whose leaders hid fundamentalist Christian motives behind a rhetoric of ‘protecting children’ – and literally invented evidence to this end.

(b) I mentioned earlier my ‘luck’ in being given a very useful item. It was one of the last surviving copies of the filmstrip used by speakers from the British National Union of Teachers when they (belatedly) joined in the campaign, as part of their attempt to prove how ‘professionally concerned’ they were for their kids. It contained a farrago of now-almost-unobtainable strips. But there was one panel from one panel, which I still use in talks I do about censorship. Called ‘When You Die’, just the opening panel was reproduced in the filmstrip, giving a wildly dishonest impression of its nature. Actually, when seen in full, it is a really weird bit of (ironic?) discourse on ‘America as heaven’ … wow. And that is my next point. What the horror comics campaign taught me was that there are important – if very complicated – politics at work behind both the campaigns, and the comics (or whatever other cultural forms) that come under attack. This became really important for me when I did my work on the censoring of the British comic Action (1976). But there again, I just got dead lucky in gaining access to archives of materials which told such a different story than the official version.

(c) But the residue that these campaigns leave behind become part of a sequence, a point brilliantly made by Geoff Pearson’s Hooligan: A History of Respectable Fears (a superb book, sad that he died just a few years ago – I was really pleased when he agreed to write an essay for my ‘video nasties’ edited collection). Thirty years on, the horror comics campaign was being cited as just the kind of campaign that was needed to ‘protect children’ from the evil of ‘video nasties’. A sort of ‘we did things better then’.

Q: In your book, Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics, you cover a lot of ground regarding UK Comics. In the case of Action, you argue: “I am confident that the ‘problem’ of Action was not a simple as ‘violence’. It was in fact a political objection’ (1989, 45). What was it about the comic that ‘stood at the edge of radicalism’, ‘of a very radical politics’ that ‘couldn’t be allowed’? (1989, 49).

Action was attacked as an example of ‘violence’ – and it certainly used conflict, including physical confrontations, as one of the vehicles of its stories. But the key thing about the comic’s various stories was their focus on confrontations with authority. Sometimes these were generically safe enough, as in the strip ‘Dredger & Breed’, which is set in the world of John le Carré and other spy narratives – but notice the evident hints at class as a dimension within the characters. Others were more overtly about contemporary, lived class experiences and conflicts – think ‘Probationer’, or ‘Kids Rule OK’ – both of which focus directly on young people’s conflicts with agents of the State. Here too, for me, the key moment came when a gap emerged between the public rhetorics and the detailed actions. Action was withdrawn ‘for reconsideration’ after a series of attacks from public figures, including politicians, moral campaigners and journalists. I was told that at the key editorial meeting a member of senior management gave an instruction to the editorial staff: ‘He told us to take out all the adult political stuff and turn it back into a boys’ adventure comic’. And when I had the luck, then, to get into their archive, and be able to reconstruct what had been intended as the story-arcs, and then compare then panel by panel with what was seen as ‘acceptable’, the shift away from any kind of class politics became brutally clear.

The point was that at a time when comics generally were losing readership, at the time of its withdrawal and castration Action was bucking the trend and seeing rising sales – and an unprecedented kind of committed readership. Pat Mills, its founding editor, doesn’t fully agree with me about this – I have a really high regard for Pat and his work over the years – but I am convinced that, far from ‘going too far’ (Pat’s view), Action was on the edge of doing something really without precedent: it was offering young boys – especially working class boys – a pretty direct mirror of their own situations, and fantasies, in a period of rising conflict of many kinds.

So the emergent politics were a very imprecise but interesting example of anti-authority rebellion – a distrusting of those with power, and an acting on (young) people’s own behalf. They were of course very unspecific, but that doesn’t entirely undo their significance. This comic was ‘on the side’ of young rebellious working class boys.

I believe that I showed this very concretely when I had the extraordinary luck to be allowed unfettered access to the IPC archive, and was able to reconstruct the pages of the comics that had been bowdlerised under that ‘take the politics out …’ regime, and identify concretely the changes/losses to the individual stories (sometimes blatant, as in ‘Hellman of Hammerforce’, where the picture of Stalin vanished; sometimes more complicated). The guts of that work appeared in the now-so-hard-to-get-hold-of Action: the Story of a Violent Comic.

Q: In your work, you have often rejected, or at least questioned, the popular use of the term ‘violence’ as a catch-all. Can you share your thoughts on the concept as it tends to be related to comics, to film, and other media representations?

You are right to call it a ‘concept’ – it is not a descriptive term. I have to refer to another essay I wrote, which will almost certainly not be known to any of your readers. It was titled ‘Violence Redux’, and appeared in a very interesting book New Hollywood Violence (edited by Steven Schneider, 2004). In it, I try to show that the concept ‘violence’ was once a very new term, replacing ones like ‘delinquency’ (which is more specific and class-located) – and that this began effectively and non-accidentally in the mid-1960s, as waves of discontent and new social and political movements emerged in many countries (student movements, anti-Vietnam War, anti-racist, feminist movements, for example). A key revealing document, because all the fears get exposed in it, was the extraordinary Presidential Inquiry into the Causes and Prevention of Violence, produced and published in the USA in the late 1960s. Mostly, it is a remarkably radical document – rooting the high levels of violence in America in slavery, extremes of wealth, and the like. But then in its final Section, it turns its attention to the anti-War movement – and suddenly the language changes. The war is not ‘violence’, but opposition to it is, and the probable causes of that are … television coverage, which ‘rouses emotions’. This gave renewed life to the linear ‘effects’ tradition of studying the media, which dominated discourse for the next twenty years. So, my insistence is that ‘violence’ is a concept, not a descriptive term. It tends to carry with it a skein of assumptions, about randomness, location in weak, prone individuals. It couples easily with claims about ‘cumulative effects’ (the more you see, the more you are influenced.) And so on. I have come back to this on a number of occasions, directly and indirectly. It leads to simple absurdities, since on its own admissions the most dangerous media materials are cartoons such as Tom and Jerry because simple ‘counting’ processes identify these as the ‘most violent’. Bonkers.

Martin Barker is Emeritus Professor at Aberystwyth University, and Visiting Professor at UWE Bristol. Following a career which began in 1969, he finally – with a small sigh of relief – retired from teaching in 2015, but is still doing research as he is able. Across his research life, he has studied (among other things) contemporary British racism, children’s comics, censorship campaigns, and a variety of particular films. But he has over the last twenty years particularly focused on the development of audience research in a cultural studies mode – including trialling and developing a mode of quali-quantitative research. He is founder and now Joint Editor of Participations, the online journal of audience and reception studies. His major audience projects include the international Lord of the Rings, Hobbit, and Game of Thrones projects, and he has led contracted research for the British Board of Film Classification on audience responses to screened sexual violence.