Adventures Under Ground-UK Underground Comix (1969 – 1982): A Memoir (1 of 2) by Dave Huxley

/Definitions?

If there is some doubt about the definition of ‘underground comics’ then perhaps the material dealt with here will be constitute a working definition. For the moment I will lean on the ‘I know one when I see one’ defence. As for ‘alternative comics’, ‘comix’, ‘ground level comics’ …

USA, UPS, Oz and International Times

Whatever uncertainties there are around the field, there can be little doubt that British underground comics owed a massive debt to their American counterparts. And unlike the debate around UK/US punk, there is no doubt about who was first – the movement clearly originated in the United States. This is not to say that there was also some stylistic influence from UK artists. British underground artist Hunt Emerson, although hugely influenced by Robert Crumb and Mad magazine, comments, ‘Leo Baxendale is of prime importance to all English cartoonists. Whether they admit it or not. He’s formed part of our general world view.’1 (interview with the author)

I can remember first seeing the work of Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton in Oz magazine and International Times in the early 1970s. Both benefitted from the Underground Press Syndicate agreement that allowed free reprinting from the various underground publishers around the world. Thus articles and illustrations could be freely reprinted by any members of the international UPS movement.

International Times also published homegrown artists such as Edward Barker. The co-founder of the magazine, Barry Miles, explains that, ‘At IT we originated our own cartoon strips, not wanting to the paper to become too American, but after about three years the work of Crumb, Shelton, Spain, Clay Wilson and the other American underground cartoonists had become so good that we started to reprint it.’ (quoted in Bizot)

As I don’t believe in throwing interesting print material away I still have these publications. The Crumb comic ‘My first LSD trip’ was reprinted on the cover of IT (14 June, 1973) with the addition of two colour overlays.

Figure 1 . Robert Crumb, ‘My first LSD trip’ IT 14 June, 1973

Gilbert Shelton was the other artist who was most widely reproduced in the British underground magazines. His Furry Freak Brothers were a natural fit with the pro-marijuana stance of most of the underground. In Oz number 25 (December, 1969) reprints a full page strip where Freewheelin’ Franklin, hassled by two rednecks, destroys them with aid of amyl nitrate.

Crumb’s work was also used in spot illustrations, sometimes with only a peripheral connection to the article they adorned. Reading these magazines at the time, it was Crumb who was particularly striking. However salacious or shocking the content, his method of rendering his drawings in a cute rounded style reminiscent of the Fleisher brothers crossed with Disney (and turned up to eleven) helped to create a visual style for the underground. This phenomenon was noticed in British art and design magazines, such as the respectable publication Art and Artists.2

Figure 2 . S Clay Wilson, cover of Art and Artists (as Art ‘N’ Artists), December 1969

Given the current reputation of some of the work in underground comics – and particularly Crumb – it has to be said that, nevertheless, as art students at the time, many of us saw the use of comics to address issues of drugs and sex etc as a liberating force. Crumb directly influenced many British artists, including Hunt Emerson, Angus McKie and Steve Bell. Bell, who later became a major political cartoonist working for the Guardian, comments,

‘The only one I copied was Crumb…it was a complete eye opener just to think that you could deal with that very real topic in a strip cartoon. Sort of warped, but I love his pen work, so that was the one who influenced me directly. I certainly copied his style.’ (interview with the author)

In 1970 I was a fine art student at Birmingham College of Art, becoming re-interested in comics of all kinds. Post-Roy Lichtenstein it was the case that comics were also semi-respectable in some art schools, although at Birmingham, as I used comic book imagery in my paintings, I was told in no uncertain terms that ‘representational painting is dead’. The 1960s had seen a gradual change from the drab conservatism of the 1950s and the early 1970s seemed, at the time, to be taking new freedoms even further, and this was seen by many students as ‘a good thing’. Greg Irons, Jaxon, Corben and others produced strange horror titles that were something from Fredric Wertham’s worst nightmares. All good dirty fun, it seemed. Looking back some of the material that was produced on both sides of the Atlantic looks like naïve juvenilia, albeit not without interest. The best has stood the test of time, and is still in print.

Availability

For those so used to the internet it can be difficult to comprehend how difficult it was to obtain somewhat obscure publications (or even some mainstream American comics in the UK) at this time. Underground publications were sold in the street in some major cities in the UK, and at various rock concerts. There was the Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed shop in London, which opened in 1969, but that covered a range of comic and science fiction material and did not specialise in undergrounds.

Figure 3. Steve Bell, Advert for Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed in KAK booklet, 1977

In Birmingham there was a similar shop, Nostalgia and Comics, but this had the same kind of stock, and underground material was not their speciality. Thus although it was possible to obtain whatever undergrounds they stocked (and these tended to be major titles like Zap) it was necessary to use mail order to try and obtain other comics. It should be pointed out that for many there was a general interest in comics that extended to anything that seemed adult or challenging. Even underground papers such as IT covered interesting mainstream publications, particularly from Marvel. Fanzine publications such as Fantasy (Comics) Unlimited, from Alan Austin, contained detailed history of Marvel and DC characters, and a large mail order section. As a collector it’s best not to look at how cheap second-hand comics could be then. But these titles also featured artwork by artists who would be central to both underground and mainstream comics. Covers were drawn by artists as varied as Kevin O’Neill and Antonio Ghura.

Figure 4 . Fantasy Unlimited covers. Kevin O’Neill , October 1973, Antonio Ghura, June 1975

Some listings also began to carry more undergrounds, such as Eddie Walsh’s Fandom, which also had short columns about comics, television and film (e.g.. in issue 13 we have ‘The next Star Wars saga may be titled Revenge of a Jedi’). Mail order was also the only way to obtain rarer American undergrounds, and it was possible to get these direct from the US, from dealers such as Bud Plant.

Figure 5 . Bud Plant leaflet, 1977

Through this period comic conventions and comic marts began to appear with increasing regularity. Comicon in London was the largest annual event, with many smaller marts around the country.

Figure 6 . Comicon leaflet, 1972

Figure 7 . Comic Mart advert from Fandom 13, 1980

These all remained an important source of all kinds of comics, even as an academic. By the 1980s it was possible to find two academics (rather more mature bearded gentlemen, Martin Barker and myself) mixing with fanboys and fangirls as the burgeoning academic interest grew in the UK.

Some readers will undoubtedly be asking where are the female or ethnic minority creators in this story? Unlike the US, where there were key contributions by creators like Trina Robbins, Melinda Gebbie and many others, in the UK, at this period, there was one major female artist, Suzy Varty, working out of Ar-Zak in Birmingham. In 1977 Heroine Comics was produced by Varty and other female artists, including Trina Robbins. The comic featured a refreshing range of different styles, including Julia Wakefield’s ‘Bull Ring’, a comedic meditation on consumerism and sexuality.

Figure 8 . Julia Wakefield’s ‘Bull Ring’ in Heroine, 1977

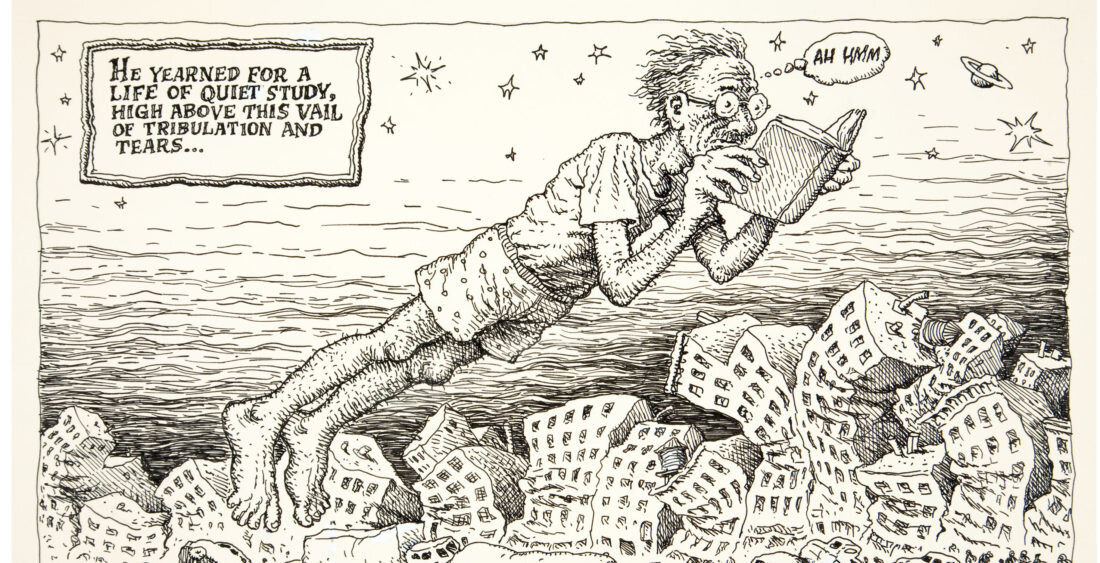

Heroine was followed by Sourcream in 1979 and Sourcream 2 in 1981, the latter featuring thirteen female cartoonists, including Fanny Tribble. Some of the strips had appeared in the feminist magazine Spare Rib, and it was published by Sheba Feminist Publishers in London.

Figure 9 . Sourcream 2, 1981

It was not until the later 1980s, outside the period under consideration here, that some female creators, such as Myra Hancock came to the fore, and Carol Bennett formed Fanny, a group of female comic artists in 1991. This would eventually lead to greater engagement with comics, with organisations like Nicola Streeten’s Laydeez do Comics, formed in 2009.

Cozmic Comics and Nasty Tales

Cozmic Comics and Nasty Tales grew out of Oz and International Times respectively, and were the two major and most easily accessible British underground comics, running from 1971 to 1975. Much of their history has been covered elsewhere, so I will just mention some of the highlights, and lowlights, of these publications. Cozmic Comics branched out into various one-off titles such as Half-Assed Funnies and Tales from the Void. As well as reprinting American artists like Crumb these comics gave the opportunity for home-grown artists such as Edward Barker, Dave Gibbons and William Rankin to see their work in print. Nasty Tales was, in many ways, very similar in content. However it became most famous for an obscenity trial based around Crumb reprints in issue 1 (1971). Although overshadowed by the earlier and more famous Oz obscenity trial, the comic was defended by, amongst others, Germaine Greer and George Perry, and eventually acquitted. This also led to The Trials of Nasty Tales, a comic giving a detailed account of the proceedings at the Old Bailey with artwork by Dave Gibbons, Edward Barker and others. All this, however, spelt the end for both these titles, and it was left to other publishers to continue

It should also be mentioned that there were some eccentric individuals who produced their own comics virtually singlehandedly. Foremost amongst them were Antonio Ghura and Mike Mathews. Ghura, drawing in a distinctly mainstream American style, produced several comics, such as Amazing Love Stories and Raw Purple (1977) whose parodies centred on extremes of sex and violence. Mathews, although using a style closer to Richard Corben, mined a similar vein of sex and violence in titles like Napalm Kiss. Both artists, writing, drawing and publishing on their own seemed intent on offending even the liberal sensibilities of other underground creators. For the more minor publisher/artists like Mathews, both printing and distribution were still a headache as he explained in a 1985 letter.

Figure 10 . Mike Mathews, letter to the author, 1985

David Huxley is the editor of The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (Routledge). He was a senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University until 2017. He has written widely on comics, including works on various artists, underground and horror comics, superheroes and also popular film. He has also drawn and written for a range of British comics, including Ally Sloper, Either or Comics, Pssst, Oink and Killer Comics. His most recent publication is Lone Heroes and the Myth of the American West in Comic Books 1945-1962 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2018).