Remembering UK Comics: A Conversation with William Proctor and Julia Round (Part I)

/Editor’s Note: Most American comic fans know of the so-called British Invasion as creators such as Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, and Frank Miller, among others, represented new voices in U.S. comics. But few have taken the time to understand the larger British comics culture — the context which these and many other gifted pop culture auteurs emerged. But more than that, we should know more about everyday comics culture — what British youth read, what forms these publications took, how stories circulated in their “ordinary” lives, and so forth.

When I first came to England in the early 1990s, I came back with a suitcase full of magazines and comics, fascinated by a parallel world of popular culture in English which was little known in America. I had read my Angela McRobbie and Martin Barker and even George Orwell’s work on the comic postcard, and wanted to understand this tradition better. I had no idea that British comics was sputtering well before I got there.

When Billy Proctor proposed a series of interviews, conversations, and essays on the British comics tradition, I jumped at the chance. I had first met Billy through our shared interests in the works of Bryan Talbot, having spent a wonderful afternoon at the home of one of the UK’s leading comics artists. I felt more of us around the world should know of this history and so for the next few weeks, I am turning control of my blog over to Proctor, who organized the “Cult Conversations” series a while back, and his colleague, comics scholar Julia Round, for a deep dive into this particular comics culture.

In the coming year, I hope to do more here on comics and comics studies as we ramp up to the release of my book, Comics and Stuff, coming in 2020 from New York University Press

=================

WP

I should state that I am likely to wax nostalgic about UK Comics, or at least, comics I read in my salad years. It seems that my childhood was a period where comic books were in abundance (I was born in 1974). Scanning the shelves of local newsagents these days fills me with sadness, to be honest, although perhaps I’m peering into the past with rose-tinted spectacles. Perhaps not. It’s not that there are no UK comics any longer—far from it. As the image below attests, shelves are teeming with British comics. But to my eyes, they all seem to be for children, less so for anyone over the age of five or six. And what counts as a ‘childrens’ comic’ seems to have shifted quite significantly since around the 1990s.

Here’s an image of UK comics’ shelves in retailer, WHSmith.

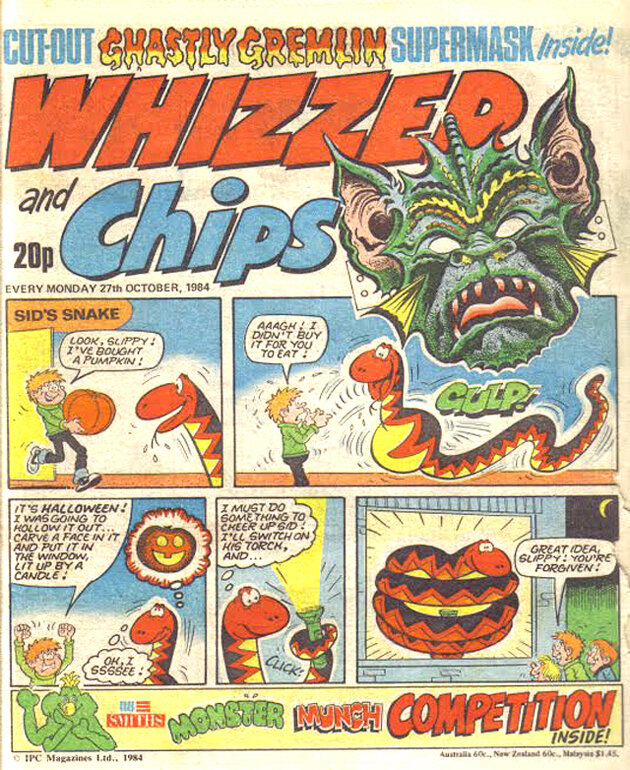

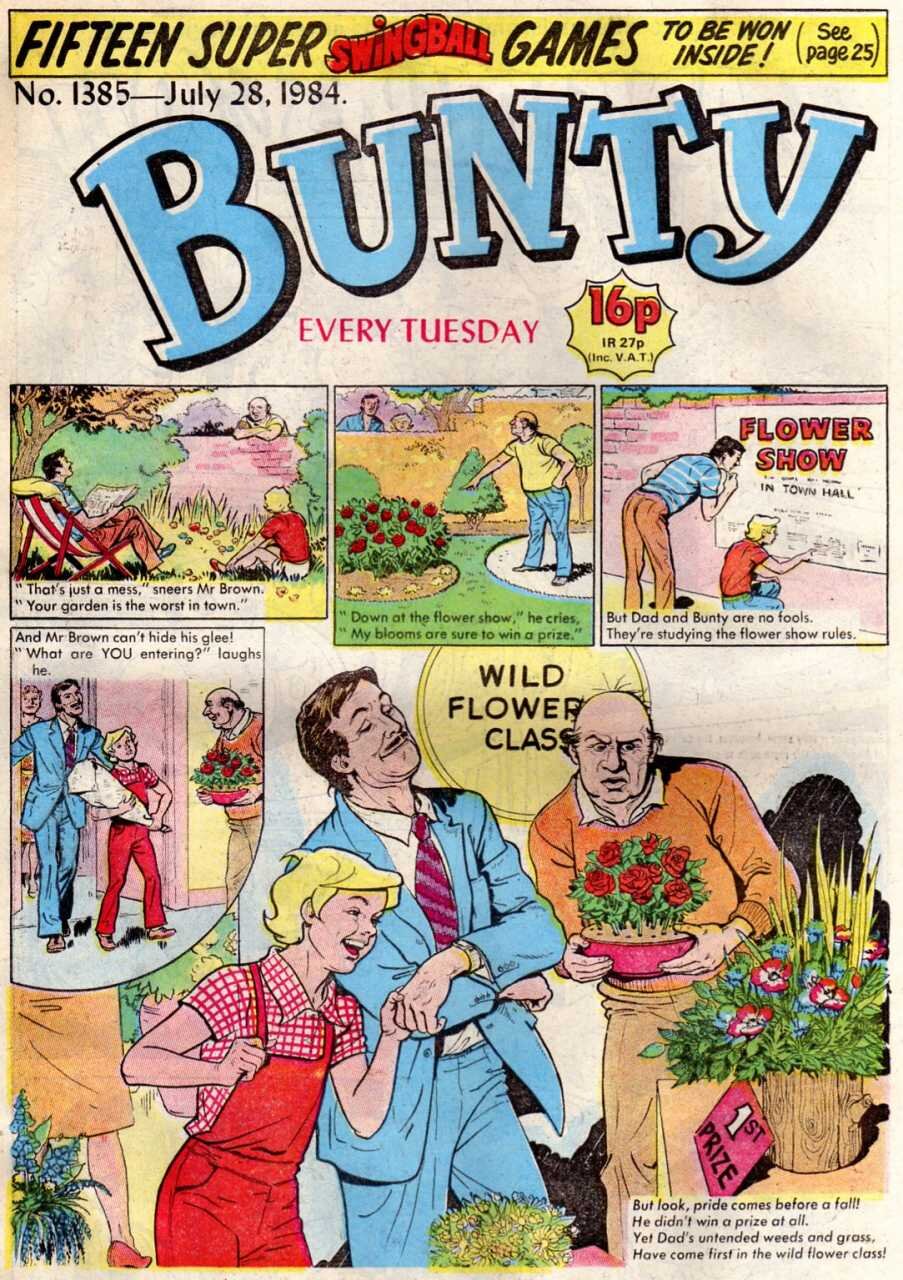

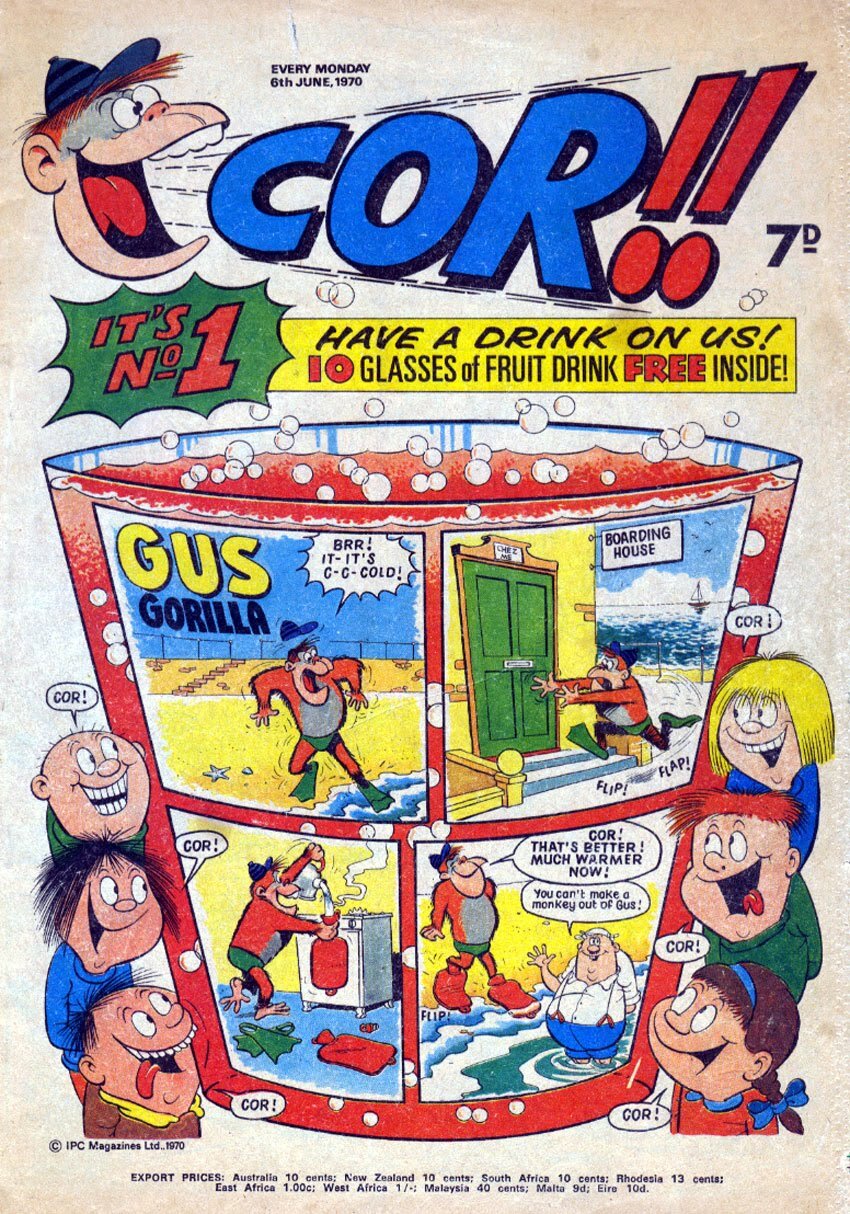

Comics were a huge part of my reading life from childhood through to my teens. Of course, I continued to read comics as an adult as well, but gravitated towards more ‘mature’ fare. Maybe it was a rite of passage, generally speaking. Many of us started out reading The Beano, The Dandy, Whizzer and Chips, Cor, etc. then moved onto titles like Victor, Action, The Eagle, Warlord, Scream, Champ, and, of course, 2000AD. I’m talking mainly here about boys' comics, but I also read girls’ comics too! I would never have bought them nor admitted to reading them to my friends though! Even at a young age, boys were dunked in the petri-dish of masculinity, learning to become MEN. If I’d finished reading my weekly purchases, I’d certainly dip into my sister’s Jackie, Bunty, and Tammy, as well as her magazines such as Look-In and Smash Hits.

Am I romanticizing our youth Julia?

JR

Not at all! — in fact, I really like the idea that working your way through the British comics, from youngest to oldest, was a rite of passage. Sadly though it seems that often it ended in the denigration and ultimate rejection of comics - I’m wondering if this attitude was almost culturally ingrained. Memory is a strange beast - if you’d asked me twenty years ago if I read British comics as a kid I think I might have said not really - not because I was lying, I just didn’t really remember much about them or how significant they were to me. But I did read them, and part of the joy of immersing myself in them again for research purposes has been having all these half-formed memories flooding back.

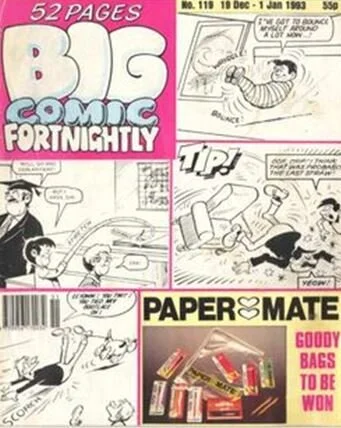

JACKIE (1980)

I had a long hiatus from girls’ comics after a particularly scary encounter with Misty when I was about 7 or 8 (for more on that check out our podcast!), but I read Jackie for years afterwards, well into my early teens, and lots before that as well. I think I started on Twinkle, and I definitely read The Beano and The Dandy enough to get some annuals for Christmas. I also distinctly remember a comic from my pre-teen years called BIG that nobody at all remembers (the lack of exclamation mark was very important since there was another pop magazine called BIG! which my newsagent always used to produce for me instead). I’ve often doubted it existed, but a spot of internet research turned up this, and tells me that it was a reprint title, collecting the best of comics such as Cor!, Buster, Whizzer and Chips, and so on. Reprinting and recycling was common practice in the British comics - not just in the souvenir hardback ‘annuals’ which would be released every year in time for well-meaning relatives to buy you for Christmas, but also between titles. Publishers believed that kids only read comics for a few years, meaning that their entire audience would be renewed every 8 years or so, which meant that popular serials that had originally appeared in one title would often be recycled into another one some years later, or collected together under a different name, like BIG.

One of the most interesting things about the British comics was the sheer range of titles. Ones for the very young, like Twinkle, with simple layouts and stories about fairies and flowers and talking animals. The anarchic comedy titles like Beano, Dandy, Cor! and the others. The war, sports and sf titles for boys that you’ve mentioned, and the school and ballet stories for girls (June and School Friend, Bunty), not to mention the romance titles of the 1950s. But as the medium developed and the number of weekly publications increased, it’s worth stressing that these were definitely not all cosy Enid Blyton-style tales - horrific bullying, ghostly happenings, mistaken identities, kidnappings, and much much more graced the pages of the British girls’ comics, and things got dark — really dark! — before the industry faltered in the 1970/80s and finally collapsed in the 1990s.

It still boggles me that an industry that at its peak was publishing hundreds of weekly titles, with circulation figures up in the millions, can have so completely collapsed! And it didn’t have anything to do with censorship or a Code like in America. British comics publishing was completely dominated by two main companies: DC Thomson, a family-run firm based in Dundee, Scotland, and Fleetway Publications (originally known as Amalgamated Press, and later renamed as the holding company International Publishing Corporation, which also gobbled up many smaller publishers such as Odhams and Newnes). These two companies were engaged in fierce competition which went on for decades. They poached each other’s creators, copied each other’s titles, kept prices low, increased free gifts, and constantly sought to outdo each other for drama and excitement - we, the readers, definitely befitted from their creativity and innovation!

The strongest memories for me are of absolutely nail-biting stories, combined with crazy layouts and amazing artwork. Fleetway sourced most of this from Spanish artists, many of whom (I found out much later) also worked for publishers like Warren in America. I didn’t know enough about the writers or artists to recognise this at the time, of course, and the British comics stories were completely uncredited for many years, which didn’t help either! Do you remember any particular artists or writers Billy/what are your strongest memories of the ones you read?

WP

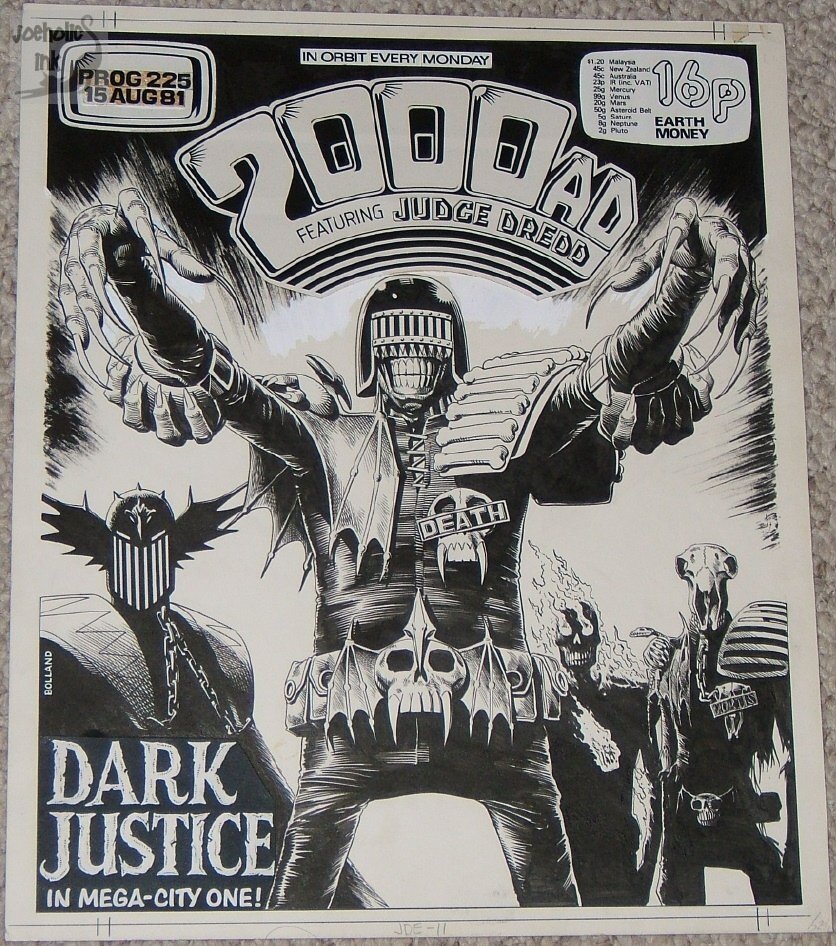

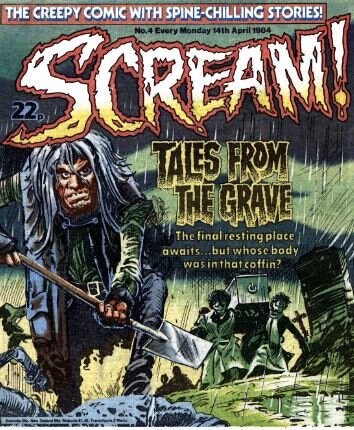

That’s an interesting question! I think it was only when I started to read 2000AD that artists and writers came to the fore. The comics I read in junior school (ages 7-11) were mostly the humor comics such as The Beano, The Dandy, and later, Champ and Scream. It was only later that I went back and recognized certain writers and artists—Alan Moore was involved in writing ‘Monster’ for Scream, which was a short-lived anthology comic that absolutely terrified me! (I’ve since bought the complete 15-issue run from Ebay.) It was in secondary school (ages 11-16) when I gravitated to 2000AD. I worked at the local newsagents as a paper-boy then, and I even remember the address where I delivered 2000AD on a weekly basis! Unbeknownst to both the addressee and the newsagent, they wouldn’t receive their copy on the day of release, but the day after. I would take the comic home to read before delivering the next day, hoping that I wouldn’t be caught for doing so. At school, there were a few kids who also read 2000AD—and I mean a few. It’s plausible that many teens read 2000AD regularly, but perhaps we were at an age where that wasn’t to be admitted in public. (Puberty came with unwritten rules after all, and comics should have been in the rear-view mirror by that time.)

But there was one boy who had a massive back catalogue of 2000AD comics, and we became fast friends. He would lend me older issues in chronological order so I could read full stories from beginning to end. Then as now, 2000AD worked on a kind of rotation. The flagship strip was, and remains, ‘Judge Dredd.’ Dredd would feature in every issue at the front of the comic, but other strips would run for a number of weeks until the story was finished, then depart for a while, replaced by other stories on a rotating basis. I distinctly remember the first time I started to recognize artists’ styles without looking at the credits. The story was ‘Nemesis the Warlock’ and the run that introduced me to the character was by Bryan Talbot. The detail is incredible, with the technique of cross-hatching used to magnificent effect. (I once spoke to Talbot about departing from that style later in his long and illustrious career and he simply remarked: “it takes bloody ages, that’s why I stopped!”) And to this day, ‘Nemesis the Warlock’ remains my absolute favorite UK comic, bar none.

Other artists, such as Brian Bolland and Kevin O’Neill, also became instantly recognizable.

Of course, this was the era when the ‘big two’ US publishers, Marvel and DC, would start offering work to UK writers and artists, many of whom cut their teeth on 2000AD. In effect, 2000AD became a breeding ground for talent, with now-familiar names crossing the Atlantic to work as hired hands for the big two: Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, Alan Moore, Peter Milligan, Warren Ellis, Jamie Delano, etc. This is often referred to as ‘The British Invasion.’

Art by Brian Bolland, who would go on to pencil Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke for DC.

It was much later, however, that writers and artists became sovereign (at least for me). So while I may be au fait with many artists’ styles nowadays, that occurred retroactively, and even more so when I began studying comics as an academic. I must say that my scholarly work, however, is focused more on US superhero comics than UK comics, although I hope that I’ll rectify that in future—I’ve been keen on doing some work on Scream as it seems broadly neglected in academic spheres.

In a nutshell, my strongest memories are of excitement and horror! Roy of the Rovers always left me gasping with exertion, as did ‘We are United’ in Champ. I was an avid football fan, and these strips seemed akin to the real thing—perhaps more so!

Also in Champ was ‘The Sinister World of Mr Pendragon.’ I would read it under the bed covers (with a flashlight), and would be so paralyzed with fright that I wouldn’t dare go to the bathroom in case the monsters ate me! ‘The Dracula Files’ in Scream had a similar effect.

What about you Julia? Did you recognize artists or follow a particular writer? As you said, of course, many strips went uncredited at the time, but I believe Action and 2000AD instigated a shift towards proper accreditation (I may be wrong about that but I’m sure you’ll tell me!)

SCREAM’S ‘THE DRACULA FILE’

JR

If you go back far enough, there actually used to be credits in British comics - you can find them in Eagle (1950–69) and some of the romance titles of a similar era, but by the 1970s this wasn’t standard practice any more. Some smaller companies like Top Shelf did carry on crediting their artists and writers, but the British Big Two definitely did not. Part of each comic’s editorial team’s job was actually to paint over any signatures that artists dared to add to their work! - of course this led to lots of more subtle signatures and references bring inserted, and it can be lots of fun to try and spot these. The artist John Armstrong was particularly good at hiding his initials in his artwork!

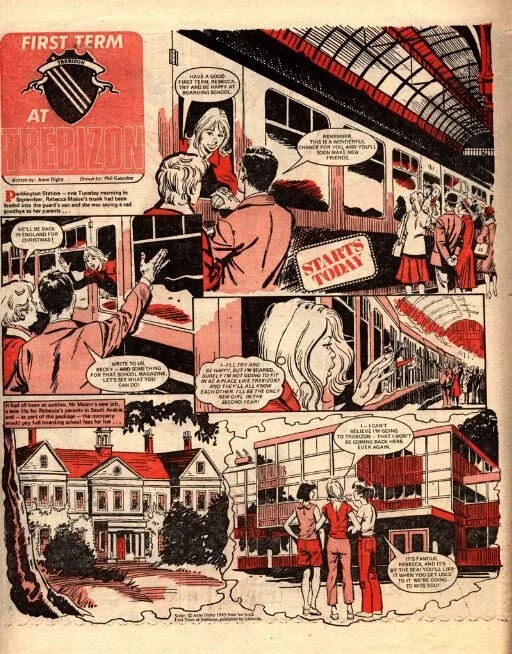

I think 2000AD was the comic responsible for bringing creator credits back when it launched in 1977 - its art editor Kevin O’Neill basically said ‘This is bullsh*t’, put them on, and told Fleetway management they were experimenting. They’ve been there ever since! The idea was then picked up by Tammy editor Wilf Prigmore (credits first appeared in Tammy on July 17, 1982, and continued until February 11, 1984). He remembers this move as also being driven by one of his writers, Anne Digby, as the comic was serialising an adaptation of her Trebizon school story novels and she thought adding her name might help them sell.

Dr William Proctor is Senior Lecturer in Transmedia at Bournemouth University, UK. He has published widely on various topics related to popular culture, including Batman. James Bond, Stephen King, Star Wars and more. William is a leading expert on franchise reboots, and is currently writing his debut monograph, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, and Transmedia Histories (forthcoming, Palgrave). He is the co-editor of Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman, Routledge 2018), and Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Promotion, Production, and Reception (with Richard McCulloch, University of Iowa Press 2019).

Dr Julia Round is a Principal Lecturer in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, UK. She is one of the editors of Studies in Comics journal (Intellect Books) and a co-organiser of the annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference (IGNCC). Her first book was Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (McFarland, 2014), followed by the edited collection Real Lives, Celebrity Stories (Bloomsbury, 2014). In 2015 she received the Inge Award for Comics Scholarship for her research, which focuses on Gothic, comics, and children’s literature. She has recently completed two AHRC-funded studies examining how digital transformations affect young people's reading. Her new book Misty and Gothic for Girls in British Comics (forthcoming from UP Mississippi, 2019) examines the presence of Gothic themes and aesthetics in children’s comics, and is accompanied by a searchable database of all the stories (with summaries, previously unknown creator credits, and origins), available at her website www.juliaround.com.