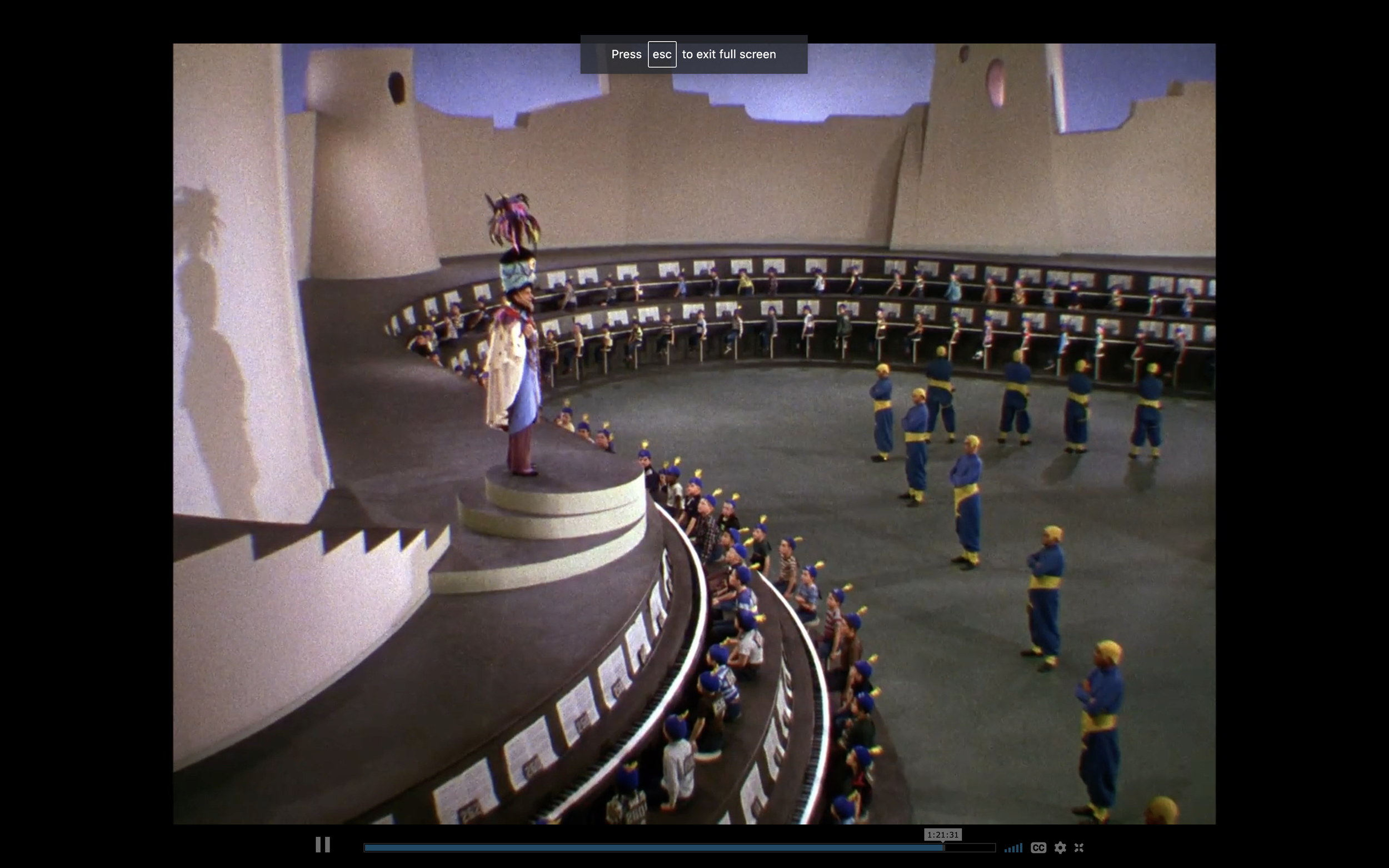

Now, having catalogued the various items that make up the Doe-Mi-Doe duds, we can better appreciate how they both fit into the story as a whole and enhance it by adding various levels of meaning that might not be immediately apparent. First, the Doe-Mi-Doe duds represent the apex of Dr T.’s sartorial ambitions: seen in terms of the progression of his increasingly outlandish wardrobe choices, they reveal Dr. T in his full character. Completing a radical 180- degree transformation from the suit and tie he wears initially, the Doe-Mi-Doe duds chart his evolution (through Bart’s eyes) from being merely a strict, disciplinarian piano teacher in the beginning to a full-blown dictator and ruthless tyrant at the end. And while he first appears in Bart’s dream looking refined and sophisticated like a conductor, at the end, he looks garishly caricaturish, resembling more of a marching-band leader than an orchestra maestro.

Additionally, these Doe-Mi-Doe duds serve to contrast him with two other major figures, namely, young Bart Collins and the plumber Zlabadowski. Whereas Terwilliker’s attire is luxurious and extravagant, both Bart’s and Zlabadowski’s attire is mundane and pedestrian. Bart wears the striped shirt and denim pants typically associated with all-American youngstersin the ‘50s. Zlabadowski’s outfit, though not working-class, certainly bespeaks a sort of bland “everyman” quality. In his tan jacket and simple slacks, he signifies a sort of “ordinary Joe” type. Interestingly, he’s not outfitted in the sort of gray and grimy overalls one often associates with plumbers, but this makes narrative sense, since it’s his paternal qualities, rather than his plumbing skills, that the film emphasizes. He wears the look of an easygoing, if somewhat boring, middle-American dad.

Also, unlike Dr. T’s clothing, each item of which seems unique and one-of-a-kind, the clothes that Bart and Zlabadowski wear look as if they are mass-produced, churned out by factories rather than hand-stitched. This is particularly true of Bart’s “Happy Fingers” beanie, presumably made in a factory in large bulk quantities. When Bart puts it on, it not only looks ludicrous on him, but it also anonymizes him, so that when the busloads of kids arrive in the final scene, Bart becomes only one rather unremarkable kid in a sea of kids, all of whom look generically the same, visually speaking. In contrast, Dr. T’s clothing is meant to set him apart as a unique individual, with an idiosyncratic style that is all his own. His feathery, ornate bearskin hat suggests that he, like it, is one-of-a-kind, singular; on the other hand, Bart’s mass-produced beanie supports the notion that he, like all the other kids, is essentially indistinguishable and replaceable.

The Doe-Mi-Doe duds also heighten the sense of Surrealism. At some level, any breakout into a musical number inherently forces the audience to realize that what’s on screen is a departure from “the real.” But here, the entire visual space, from the set decoration to the servants in their colorful formalwear, is conceived in such a way that the audience instantly knows this is a dreamlike realm of fantasy and imagination. Additionally, the song lyrics that Dr. T sings as he’sbeing dressed are themselves utterly nonsensical, veering occasionally into absurdity. He begins to rattle off names of things that don’t actually exist in the real world and are just made- up juxtapositions, such as “Chesapeake mouse” or “Hudson Bay rat.” In this sense, the lyrics call to mind the process of free association, in which patients in psychoanalysis are encouraged to let words bubble up from their unconscious, even if the connections between those words aren’t immediately apparent. Dr. T’s spouting of gibberish does indeed have this sort of free- associative quality, which becomes particularly apparent towards the song’s end when he references food rather than fashion, e.g., “pretzels” and “bock-beer suds.” And the Doe-Mi- Doe costume itself seems to embody Surrealist principles: it’s a hodgepodge of fancifully bizarre items that seem joined together purely as a result of whimsy and imagination (e.g., a feather epaulet, a white cape, assorted medals).

Taking this line of reasoning further, in psychoanalytic terms, this musical extravaganza can be seen as an expression of Terwilliker’s unbridled “id.” Literally, the lyrics of the song are a relentless recitation of “I want” statements, repeated over and over, and reformulated to encompass more and more outrageous articles of clothing. Like a child, Dr. T unabashedly declares that he desires certain items, and his obedient manservants promptly cater to his every whim. In fact, the song expresses a sort of dialectical relationship between Dr. T’s identity as a terrorizer of children, on the one hand, and his identity as essentially a big child himself, full of wants and needs (again, the notion of the unbridled “id”). It’s probably not mere coincidence that, during the song-and-dance, Terwilliker requests being dressed up in “silk and spinach,” or mentions clothing made of “liverwurst and camembert.” On the one hand, those are plainly absurd propositions (using food as garments), but also, at the basic level of child psychology, those appear to be specific foods that many children find detestable or revolting, or would associate with punishment. Through this song Terwilliker expresses both the unrestrained impulses of an undisciplined, spoiled child, while at the same time referencing the sort of unpleasant culinary experiences (e.g., eating spinach or liverwurst) that children often think of as punitive. Thus, his dictatorial qualities come to the foreground: he is both a child to be indulged, and a tyrant who sparks fear in other children.

Additionally, Henry Jenkins has written about how this film can be viewed as a veiled critique of fascism and dictatorship in the post-WWII era, and the iconography of the Doe-Mi-Doe duds fits neatly into this aspect. Specifically, Jenkins points out that in both early script drafts and the finished product, there is a clear linkage between the Fuhrer-like Dr. Terwilliker and Adolf Hitler. See Henry Jenkins, “No Matter How Small: The Democratic Imagination of Dr. Seuss,” Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture (hereinafter, “Jenkins”), p. 201. For instance, Jenkins notes how the grand procession of Terwilliker’s henchmen towards the end has intentionally been choreographed to resemble the Nazi rallies depicted in Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. (Jenkins, p. 201). In the imagery of the Doe-Mi-Doe duds themselves, the antifascist commentary is equally present. As noted above, Dr. T wears a large number of medals as part of this costume. These have strong military connotations. On each shoulder, he sports the sort of epaulets typically worn by military officers. His imposing bearskin hat subtly likens him to the bombastic bandleader of a jingoistic military marching band. Strutting around in his Doe-Mi-Does and surrounded by goosestepping goons, he more closely resembles a military dictator than a benevolent leader or instructor.

So far, we’ve catalogued how the Doe-Mi-Doe duds operate at two distinct levels of meaning. One is informational, in service of a narrative function (telling the specific story of the conflict between Terwilliker and Bart). The other way in which this costume functions is at a symbolic level, i.e., alluding to the wider struggle against fascism, and specifically against Hitler’s Nazi Germany, that America had just emerged victoriously from. As Jenkins points out, this aligns closely with Seuss’s own authorial intent. Seuss’s interest in exploring themes loosely described as Surrealist, drawing upon theories of the unconscious, or child psychology, is also detected here. Thus the two levels described above (narrative and symbolic) in fact correspond to the first two levels of meaning that Roland Barthes identifies when he proposes that there are three levels of meaning when looking at a film. See Angelos Koutsourakis, “A Modest Proposal for Re-Thinking Cinematic Excess,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video (hereinafter, “Koutsourakis”), pp. 706-707.

The Barthian “third meaning,” however, consists of a layer of meaning that often operates outside the range of the author’s own intentions. Instead, it often manifests as what is described as an almost “fetishistic” interest in surface details. Furthermore, often operating against, or frustrating or impeding, the narrative flow, it can also take the form of an indulgence in what theorists often call “cinematic excess,” a fixation on certain filmic aspects of the medium that ostensibly serve no narrative impulse but rather satisfy an aesthetic impulse beyond linear storytelling. In fact, these qualities have led some theorists to assert that it is closely connected to a sort of queer sensibility and viewership. (Koutsourakis, p. 707). I would argue that this Barthian notion of a third meaning has particular relevance to Dr. T and his Doe- Mi-Doe duds.

One of the most interesting aspects of the song-and-dance routine is that, in singing it, Dr. T recites a litany of items that are in fact not ever put on him, and which never appear on screen. Rather, they are merely alluded to, but do not actually comprise the components of the Doe- Mi-Doe duds he actually wears. Thus, he speaks longingly about items such as a bolero, a gusset, Chamois booties, a dickey and other assorted items, none of which actually materialize for him. In effect, Terwilliker is reading out loud a long list of clothing items that are simply not present. Of course, his valets are indeed dressing him up in assorted fineries, but those fineries are not the actual ones he speaks of in his song.

What is one to make of this? Perhaps one reading is simply that he’s an oaf, that he is stupid and doesn’t quite realize that he’s not getting what he’s asking for. Certainly, one aspect of his persona is indeed that he is a buffoon, so this may indeed be a plausible explanation. But to me this doesn’t seem like the correct reading. Terwilliker certainly seems to know exactly what each of the articles of clothing are; his eyes seem to light up as he mentions each by name. It seems then that the constant mismatch between what he requests and what he gets speaks, in effect, to a gap between desire and reality. There’s a disjuncture between the spoken words he utters and the physical reality he encounters, the material objects he receives. In any event, this echoes the sort of tension that exists between the world of pleasures that a gay man living in a heteronormative world would like to experience and the actual pleasures that he is allowed to experience in that same world. The act of singing about each clothing item takes on the tone of a kind of fetishistic wish fulfillment when the scene is re-interpreted in this light. It also goes hand-in-hand with the notion of “excess” or “surplus” in the most literal way possible, as he’s calling out for many more items of clothing than he could possibly hope to wear at once (i.e., an overabundance). Perhaps the strongest argument that there is indeed a “third meaning” to this scene is a transgressive element that some viewers might have missed: much of the clothing he says he wants are actually items of women’s clothing, e.g., a brocaded bodice, a peekaboo blouse, bright blue bloomers (women’s underwear) or a Mother Hubbard (a gown worn by women in the Victorian era). As a man who seems obsessively fixated on fashion, style and beauty, Terwilliker himself seems to be coded as gay, queer or transgender. When one considers that his coterie of attendants in the scene are all attractive young men, thus subverting the traditional (straight) male gaze that seeks to locate the female body as the site of sexual desire, the looming presence of a queer sensibility seems all the more plausible. Thus, even though Terwilliker ostensibly seeks to marry Bart’s mom, competing with Zlabadowski for her, this musical number suggests a subtext in which he’s coded as a repressed or closeted gay man. At any rate, this reading of the Doe-Mi-Doe scene is not necessarily authoritative or “the truth,” but merely one possible interpretation that emerges when viewing it through the lens of Barthes’ “third meaning.” Since the Barthian third meaning exists outside of authorial intent, it’s quite possible it could still be meaningful even if Seuss himself never intended the film to be interpreted this way.

Bibliography of Works Cited

Henry Jenkins, “No Matter How Small: The Democratic Imagination of Dr. Seuss,” Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture (2003)

Angelos Koutsourakis, “A Modest Proposal for Re-Thinking Cinematic Excess,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video (2021)

David Ling is currently a second-year graduate film student in the Film and Television Production MFA program at USC's School of Cinematic Arts. Before enrolling in the program, he spent time as an entertainment lawyer, filmmaker, and film journalist in New York City. His short film "San Gennaro" premiered at the New York Short Film Festival in 2018, and his film reviews and filmmaker interviews have appeared in papermag.com. He received his bachelor's degree from Harvard College, where he was the recipient of the Thomas T. Hoopes Prize in his senior year.