Turning Red: Ming Lee and Authority

/A few years ago, I was interviewed by a high school student, Alice Shu, who impressed me with her intelligence, curiosity, and passion. She has since come to USC and I was thrilled to learn she was going to take my Imaginary Worlds class. Hers was one of the best papers I read on the first assignment and so I wanted to share it with my blog readers.

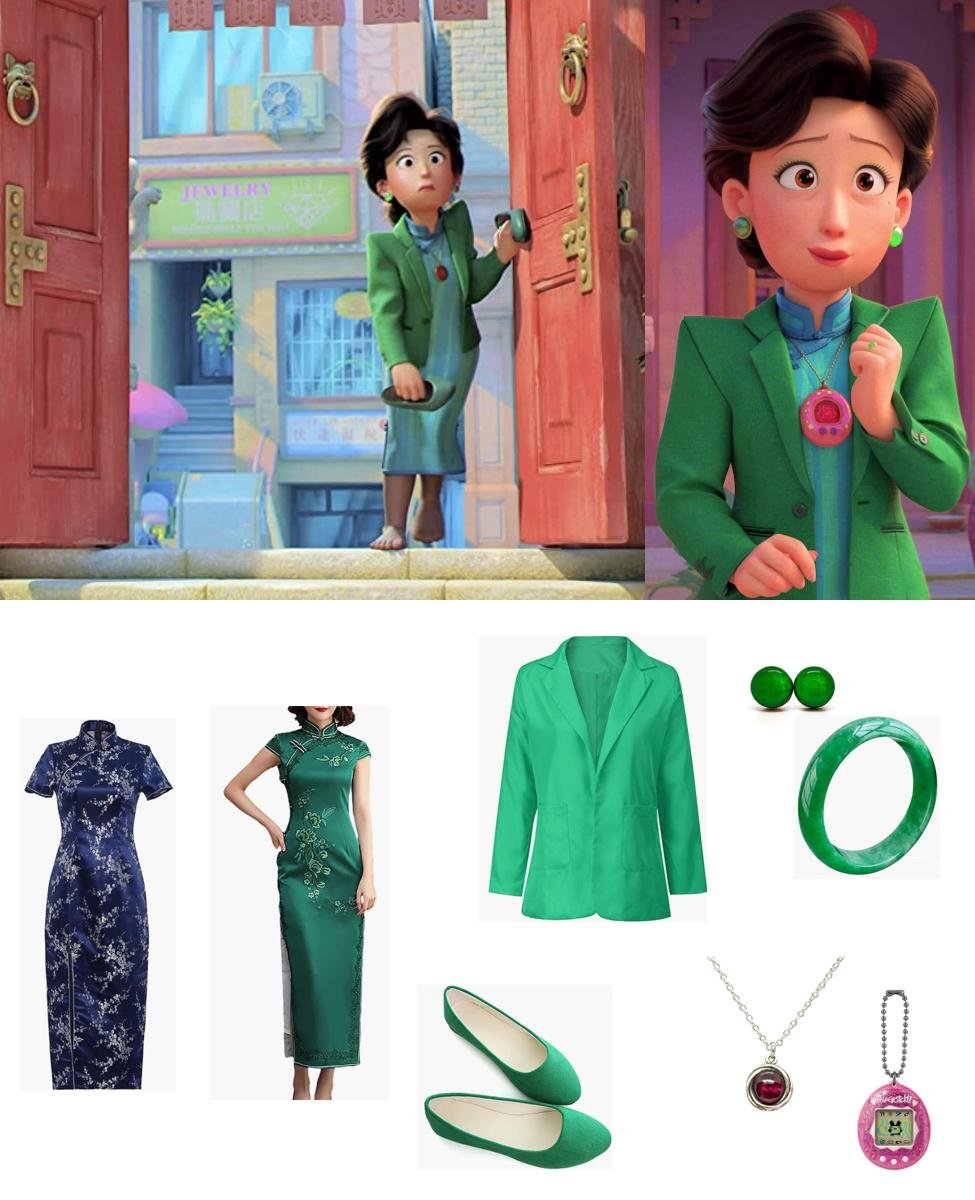

Turning Red Costumes: Ming Lee and Authority

By Alice Shu

Historically, the stories of Pixar Animation Studios tended to feature white-coded characters, whether they be human or not— consider Woody, Buzz, Mike, and Sully, all voiced by white actors. Slowly, the films began featuring more diversity with side characters like Frozone and Russell, but it has only been recently with 2017’s Coco that uses an essentially complete non-white cast. Like Coco, director Domee Shi’s Turning Red uses cultural traditions as allegories for generalizable themes like family and adjustment. As a toddler, Shi had moved from China to Toronto, and her adolescence was defined by 2000s pop culture and Chinese culture, both of which play major aesthetic roles in the film (Tangcay).

Turning Red’s story is straightforward but laced with symbolism. Chinese-Canadian Meilin “Mei” Lee attempts to maintain a close relationship with her mother Ming, who places high traditional and academic expectations onto her. Together, they run their family temple devoted to honoring their ancestors, of which the women (including Ming and Mei) hold an ability to transform into powerful red pandas. For adolescent Mei, the emotion-triggered power becomes volatile but eventually profitable, and her manipulation of the ability draws disapproval from her family. Mei spends the film managing her family’s pressure and her new social popularity to negotiate a true identity.

Ming largely foils Mei’s impulses and stands as an intimidating force within the narrative. Like Mei, her identity is also re-assessed and these changes are expressed in both characters’ costumes, which remain static for most of the film. Analyzing Ming’s costume in particular demonstrates its role in establishing her as a complex authority shaped by cultural and familial standards. In addition, Turning Red’s costumes provide more insight into the film’s setting, highlighting the role of detail in characterizing imaginary worlds.

First, Ming’s dress and accessories establish her cultural authority within the film by drawing on Chinese traditions. She wears a qipao, a traditional Chinese dress that has become iconic along with kimonos and hanbok in symbolizing East Asia in media. Her qipao displays key identifying features, including the slit, curved collar, and knotted fastenings, proving its authenticity (Lee). Whenever Ming moves, the dress also has reflective properties that mimic a silky material, which is a traditional aspect of Chinese fashion (Lee). The dress is complemented by her home surroundings, which also feature Chinese iconography in the form of paintings, calligraphy, and furniture. Similar to how Mark Wolf associates relatability with audience acceptance of design, our acknowledgement of the inspired motifs allow us to associate Ming with tradition despite her existing in a fictional world (Wolf). By accepting this consistency the world provides a ripe setting for Mei’s conflicting narrative.

In addition, her jewelry also holds heavy cultural significance and association with her family. Her earrings and ring are made of jade, a highly valuable stone that symbolizes balance and wisdom (Shan). The Lee women also wear jewelry that hold and represent their Red Panda transformations, a destructive force that contrasts with the serenity of their green outfits. The transformative gift is passed between the family’s female members, and this maternal connection is evident when Ming rubs her symbolic pendant when nervous about her daughter. The lacquer also appears in their family temple, with the main shrine being surrounded by lacquer furniture. Interestingly, each aunt’s jewelry varies in terms of the object and style, be it earrings, a hair clip, or, like Ming’s, a necklace. All the pieces, however, feature a reference to the red panda— with some even using the same design—demonstrating that the jewelry is personalizable but serves to unify the women in their commitment to tradition.

The pendant and its iterations demonstrate how specific detail can be used to advance narratives. According to Wolf, authors will select and elaborate on world details depending on their opinion on its relevance to the story. Minor details can be left for assumption by the audience, while mysterious elements require clarification. Initially in Turning Red, we see numerous allusions to red pandas in the Lees’ temple, but these are dismissed as purely aesthetic. Even when Ming explains the family’s connection to the animals, she purely states that an ancestor had admired them and that they were “blessed” by red pandas. Without prior context, the audience can interpret this purely as background information that details the temple’s purpose without anticipation for further reference. Additionally, Ming’s red necklace, while clashing with her green clothes, receives no exposition. The only interaction it receives is when Ming uses it as a comfort item, alluding to a relationship to Mei based on the scene’s context. Verbal exposition is only given after Ming confronts Mei’s panda form and explains the family’s mythology, and a close-up reveals the red panda carved into the necklace to confirm its symbolism. Thus, delaying characterization added extra weight to Mei’s sudden transformation and the family’s new stakes, proving that selecting details can advance narratives as well as expand fictional worlds.

Ming’s pendant also acts as a differentiator that separates the film’s fictional world from the known world to help legitimize setting. Turning Red succeeds as an homage due to the setting’s adherence to realism— depictions of Toronto’s population and landmarks like CN Tower confirm its sameness. It also relies on a historic time-frame to further inform aesthetics and audience reactions, as the fashion and music trends of the 2000s are prominently featured.

Further demonstration of commitment to historic accuracy can be found with the film’s climactic SkyDome. The film, set in 2002, correctly uses the stadium’s name before it was renamed to the “Rogers Centre” in 2005, twelve years before the film would begin its development. Evidently, the setting’s realism enhances the fantastical aspects of the story. Much like Ming’s costume, the primary aspects— the blazer and qipao grounded in historic authenticity—contrast with the magical, symbolized by the enigmatic pendant. The pendant then comes to symbolize a transition into the fictional aspect of the world and an indicator of the separation between the known and new.

While Ming’s costume has very real and traditional references, her daughter’s are more symbolic of her modern surroundings. Mei wears a black wire choker that sits around her neck while Ming’s pendant hangs toward her torso. Instead of a longer, fluid dress Mei’s choice of skirt and leggings divide her body, making her seem shorter while Ming’s dress elongates her figure. And, while Ming’s costume is dominated by the green to symbolize her family, Mei consistently wears more red to demonstrate her affinity towards her red panda. The only aspect that Mei retains is her green barrette, which is small and not noticeable.

Through these differences Ming is clearly defined to be grounded in her culture, and her costume serves to express her devotion to tradition in her increasingly modern context. When Mei was younger it was easier to introduce and enforce tradition within their home, as demonstrated by the numerous photos of Mei in a small reddish-pink qipao of her own. However, as proven by her choker, Mei begins to dress herself according to trends and is less expressive of the culture that her parents prioritized. The film explores this conflict as Mei negotiates with her cultural transformative qualities and aligns less with her mother’s traditional

Shu 4

expectations, a tension that is common within diaspora cultures. In this way, costume becomes a way to express culture and one’s embrace of it.

Furthermore, the externals of Ming’s costume affirm her authority within a diasporic space. While her costume itself does not allude to her role as a parent, it mirrors that of Ming’s own mother and demonstrates themes of maternal influence. Green shades reappear as an association to their Chinese background, and serves as a contrast to Mei’s social aspirations. Mei’s grandmother, the family matriarch, is introduced in a flurry of green, with her first shot dominated by a rich jade bracelet and a deep green jacket cuff. An intimate scene of Mei’s family preparing dumplings for dinner is lit by the green-blue glow of their television, which, of course, is playing an imperial Chinese drama. Mei’s family adopts signature green-blue tones, which tend to be darker and firmer— consider her grandmother’s rich turquoise cardigan— while Mei’s friends don brighter colors (Yamanaka). For example, Miriam, Mei’s friend who serves to foil Ming’s traditional expectations, wears greenish-yellow tones instead. Both characters are dressed almost completely in green, but the tonal differences establish them as important yet opposing forces in Mei’s life. Further emphasizing this tension, red and green act as complimentary colors (in reference to the color wheel theory), implying that Mei will need to compromise to preserve her relationships.

The remaining elements help confirm her authority by adding intimidating aspects. The stripes on her dress serve to elongate her height, thus making her seem taller and authoritative. This trait is enhanced by Ming being taller than all the younger characters, including her daughter, and equal height to the significant adult characters. The blazer with shoulder pads, pantyhose, and pumps contribute to a “working woman” aesthetic that also defines Ming’s livelihood in America— an early photo flashback shows her and her family attending a business convention, for example. In addition Mei and Ming are both involved in the operations of their established family temple, and Mei’s deviation from her duties causes tension between the two, demonstrating the emphasis on business industry that Ming places on herself and her family. Mei also briefly wears the blazer during a presentation to her parents in an attempt to emulate the maturity and expertise her mother is associated with. Interestingly, Ming’s blazer is always present when she conducts business or runs errands, likely to project an image of confidence to her community. However, within her closed household, she usually wears only her dress, possibly to signify being more genuine and comforting with her immediate family.

Thus, it becomes obvious that Ming’s costume helps contextualize her experiences within a diasporic context. With Mei’s family in Toronto and her grandmother and aunts in Florida, it can be inferred that a majority of her family has relocated from China to the Western hemisphere. While Mei is raised within Toronto’s Chinatown, she and her mother spend a significant amount of time outside its confines. In these less familiar contexts Ming utilizes her costume to encourage respect despite being a perpetual foreigner. Eventually, she expects mutual respect consistently from others, as shown when she becomes visibly frustrated with the school’s security guard while attempting to approach Mei during class. Evidently, Ming’s costume acts as a defense mechanism to reassure herself to maintain her authority in any context.

Despite the story mainly featuring Chinese-Canadian characters, it focuses more on the generational mother-daughter relationships. Mei’s affinity toward modern, Western trends does intensify tension with her mother, but this merely represents general conflicts of interest that characterize diminishing maternal relationships. In addition to representing an affirmative position within a foreign context, Ming’s blazer symbolizes her overprotectiveness towards her daughter. The wide shoulder-pads assist in Ming’s body overshadowing Mei during furious acts of maternal protection, demonstrating a perceived control over her. The blazer also clashes with the casual outfits that surround her, further characterizing her overprotectiveness as strange, and according to Mei’s peers, embarrassing or “psycho”. Refreshingly, the source of Mei’s shame is not of her family’s Chineseness; only once does another character disparage their traditions, as nemesis Tyler briefly yells for Mei to “go back...to your creepy temple.” Instead, it’s Ming’s closeness that is perceived as strange by others, instead of her culture, which diasporic films tend to hyperfocus on as sources of conflict.

Certainly, though, Ming’s cultural designs inform her confidence. Production designer Rona Liu and director Domee Shi describe Ming as “controlled and elegant”, and her design aims to emulate the ladies of 1960s Hong Kong (Yamanaka). Historically, this period is said to be the “second golden age” for qipaos amidst the less glamorous Communist China (Lee). Ming also wears the dress well; the stiff collars serve to display a woman’s good posture, and Ming is almost always poised and composed, emulating the traditional values of the outfit.

Interestingly, Ming’s qipao also differs drastically from the costume choices of her relatives. Mei’s aunts are dressed very immigrant and very 2000s— chunky sandals, zebra-print boots, tracksuits, and, of course, a puffer vest for the predictably cold weather. While the relatives dress casually, Ming’s costume emulates elegance and professionalism. Considering that Ming is geographically isolated from her relatives in Florida, her outfit maintenance can help provide an impression of success and assurance, especially as her own mother, who, like Ming, maintains high expectations for her daughter.

Halfway through the film, a shift in Ming’s role becomes apparent. Around her Toronto community, Mei, and her husband, she is able to intimidate and welcomes respect. However, around her mother and relatives (referred to Mei as “aunties”), she becomes defensive and more timid. Despite being the same height as her mother, she looks downward when being addressed, and her voice becomes less firm. During the climax Ming’s internal fragility and frustration with her family act as a deviation of her otherwise consistent character. Her blazer can then be interpreted as a shield from her family to preserve an internal pride that becomes diminished around her family.

Once the family’s generational tensions are resolved, though, their accommodation can be expressed through new additions to their costumes. Prior to the climax Ming wears a pendant that holds her sealed panda spirit, but after it breaks it is replaced with a red tamagotchi, a relic of the trendy concert that Mei attends. The theme of cultural adjustment continues across Mei’s family, as her grandmother’s jade bracelet is replaced by a red 4-Town charm, which represents a band that the family consistently disapproved of. The combination of modern media and the red colors symbolize a coherent acceptance of the family’s adjustment to a new era defined by acceptance.

Ming’s costume successfully characterizes her complexity and authority within Turning Red’s narrative. First, small details and ornamentation establish her as a character prior to the start of the film. The blazer, pendant, and ring allude to previous struggles of adjustment, angst, and determination in relation to her family and diaspora. The dominant green-blue tones demonstrate her alignment with the traditional expectations of family and tradition, creating a symbolic cohesion that defines the film. While the blazer and dress represent aspects of clashing worlds, the color and silhouettes allow for an elegant combination to guide our expectations of her poised character. Turning Red’s creative team undoubtedly succeeded in using her costume to extend her character in an evident demonstration of costume and narrative design.

Works Cited

Lee, Ching Yee. “How the Qipao Became the Quintessence of Chinese Elegance.” The Collector, 21 Feb. 2022, thecollector.com/how-qipao-became-timeless-chinese- elegance/.

Shan, Jun. “Importance of Jade in Chinese Culture.” ThoughtCo., 6 Dec. 2018, thoughtco.com/ about-jade-culture-629197.

Tangcay, Jazz. “‘Turning Red’: How Anime and Teen Bedrooms All Feature in Production Design.” Variety, 11 Mar 2022, variety.com/2022/artisans/news/turning-red-how-anime- teen- bedrooms-and-easter-eggs-all-feature-in-production-design-1235202044/.

Wolf, Mark. “World Design.” The Routeledge Companion to Imaginary Worlds, 1st Edition, Routeledge, 17 September 2017.

Yamanaka, Jeanine. “Creating the Look of Disney and Pixar’s ‘Turning Red’.” SoCal Thrills, 8 Mar. 2022, socalthrills.com/disney-and-pixar-creating-the-look-of-turning-red/.

Alice Shu is a USC undergraduate (class of 2025) studying Communications and East Asian Area Studies. She comes from a Chinese-American and Bay Area background that has informed her interests in intercultural communication. While at USC, she has developed interests in fandom studies and entertainment industries, particularly themed entertainment. Her favorite attraction, predictably, is the Mad Tea Party. She currently works with social media platforms on sales and marketing.