“Part of Your World”: Fairy Tales, Race, #BlackGirlMagic, and The Little Mermaid

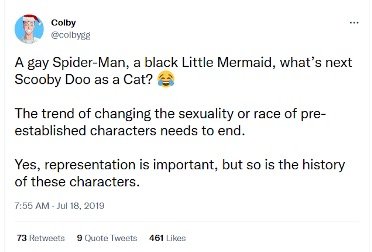

/In 2016 Disney announced a live-action adaptation of its 1989 animated film The Little Mermaid. Loosely based on Hans Christian Andersen's 1837 fairy tale, the animation earned critical acclaim, took $84 million at the domestic box office during its initial release, and won two Academy Awards (for Best Original Score and Best Original Song). Given Disney’s recent foray into creating live-action adaptations of some of its most successful animated films, it’s no surprise that The Little Mermaid was added to the list. Yet controversy rose when Black actress Halle Bailey was announced as Ariel in July 2019. Among the critiques was the argument that the adaptation should be as close to the original as possible, and the original featured a white mermaid; that if a Black character was re-cast as white in a remake there would be uproar; and while representation in all forms is important it shouldn’t override the history of the characters (Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1: Tweets discussing the casting of Ariel when Halle Bailey was originally announced in 2019

“This film ruined my childhood!”

Adaptations and remakes are often contentious topics because fans can have deeply emotional connections to the original text. Disney animations in particular often hold a nostalgic appeal for adults who grew up with the original films, and for whom they hold ties to a different - perhaps better - time. Yet negative responses to remakes which feature Black actors go beyond the ‘purist’ argument which states that adaptations and remakes should remain true to the original. A key example of this is the 2016 Ghostbusters remake which featured an all-female team of ghostbusters. The gender-swap of the ghostbusters themselves is criticized, but the majority of vitriol was directed against Black actress Leslie Jones. We have seen over the last decade or so the way that social networking sites can “promulgate sexually violent discourse and expand the opportunities to shame and humiliate women” (Horeck 2014, 1106). Twitter became one of the main spaces used to target Jones, with the star herself sharing just some of the many horrific tweets (Figure 1.2) that she had been sent:

Figure 1.2: Racist tweets directed at Leslie Jones following the 2016 Ghostbusters reboot

This language clearly shows the racism inherent in many viewers’ reactions to the film, and while this overt hate speech is horrific to see, there were other, more insidious racist responses to the film. One of the most frequent reasons for dislike of the Ghostbusters reboot was that it affected fans’ memories of the original - a common refrain highlighted in discourse around the film was that it ‘ruined my childhood’. Nostalgia thus became a coded way for some fans to perform racism, framing a childhood classic - where straight, white men were the default in film and television - as the norm and any attempt to change that as ‘wokeness gone mad’.

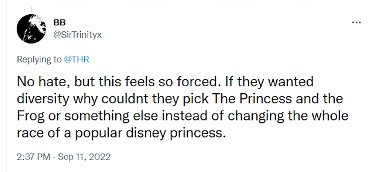

We see some of these more covert racist responses in reactions to The Little Mermaid. The trailer for the adaptation was released in September 2022, giving viewers their first glimpse of Halle Bailey as Ariel, singing “Part Of Your World”. Immediately comments began circulating on social media sites criticizing the casting as Disney pandering to the woke brigade, diversity for diversity’s sake, and another example of social justice warriors ruining popular culture (Figure 1.3):

Figure 1.3: Tweets responding to the first The Little Mermaid trailer, released in 2022

For these viewers then, their opposition to the recasting of Ariel isn’t because they’re racist; it’s because they see a concerted effort being made in popular culture to force an ideology, they feel isn’t necessary, despite that ‘ideology’ being an attempt to redress the decades of racism evident in both the production of film and television content and the representations within that content. Of course, this is still racism. It’s just couched in language that frames these as legitimate concerns. So, while questions like ‘instead of remaking this film why don’t they produce a film based on African folklore?’ may seem valid on the surface, they ignore the systemic racism within the industry and the difficulty in pitching, commissioning and making a profit on non-white content.

Before Halle there was Mami Wata…

While the original fairy tale from Hans Christian Andersen does describe Ariel’s character as “her skin was as clear and delicate as a rose-leaf, and her eyes as blue as the deepest sea” this does not mean that there were no mermaids who were of color. In fact, water spirits and Black mermaids existed even before Christian Andersen’s 1837 fairy tale. It is important to note the global history of mermaids and water spirits due to the fact that the existence of Black characters in fantasy, magical realism, and science-fiction is often non-existent. If we think about this from an Afrofuturistic lens, these early Western tales did not see Black characters as even being a part of these narratives. The waters have always been seen as a sacred space literally and figuratively within African folklore. Housed within many African traditions, the water serves as a bridge between otherworlds, life and the afterlife. And the sea deity Mami Wata or La Sirene (which translates as Mother Water or Mother of Water) serves as the beginnings of many African mythical tales. Described as having a female human torso, sometimes with a serpent wrapped around her, with a tail like a fish, and hair that can be straight, curly, or wooly the image (see Figure 1.4) could be likened to that of Halle Bailey. Nevertheless, the idea of mermaids has had a long African tradition. In South Africa, there is a myth from the Khoi-san people about the Karoo Mermaid that was discovered in the Cango Caves, in Mali the Dogon people have an origin story involving fish creatures called “nommos”, and in Nigerian Igbo tradition Mmuommiri ("Lady of the waters"). The water spirit also translates into Caribbean and South American tales through the orishas of Yemonjá (or Yemanjá) in Brazil and Yemanya (or Yemaya) in Cuba; and River Mumma, River Mama in Jamaica, and Maman de l'Eau ("Mother of the Water")/Maman Dlo/Mama Glo in Dominica.

Figure 1.4 [l-r] Sculpture of the African water deity Mami Wata. Nigeria (Igbo)-Original in Minneapolis Institute of Art and Dona Fish Ovimbundu peoples-Angola-Private Collection-Photo by Don Cole

Moreover, this narrative has and continues to be re-written to include and normalize Black bodies in the fantastical and mythical space. For example, author, filmmaker and Afrofuturist Ytasha L. Womack brings attention to the presence of these magical creatures in her chapter “The African Cosmos for Modern Mermaids (Mermen)” in her 2013 book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture; Afro-Futurist artist, writer, and educator D. Denenge Akpem recreated her own water fairy tale reminiscent of African mermaids by transforming herself into a space-sea-siren-hybrid-human-jellyfish for a 2006 exhibition show at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA)-Chicago; and Nigerian-Welsh writer Natasha Bowen would create a literary series of African mermaids based in West African tradition through her YA/fantasy novels “Skin of the Sea” (2021) and “Soul of the Deep” (2022) which follows Simi, a ‘mami wata,’ that travels across sea and land in search of the Supreme Creator. Additionally, Ta-Nehisi Coates makes references to Mami Wata in his 2019 novel "The Water Dancer" as well as Nalo Hopkinson making the key figure ‘Lasiren’ a part of her 2003 erotic historical fiction novel “The Salt Roads,” and the 2022 film Nanny depicts the figure of Mami Wata in relation to the main character Aisha. Each of these mediums of past and current history provide a plethora of historical context for the casting of Halle Bailey in the role of Ariel. As noted by Bowen, “I think speaking from Black mermaids, we need to see ourselves in positions as magical creatures. There's all the furo about Black people in fantasy. And I think that it's important for us to see ourselves — to have that freedom of imagination. And I think it's important for everyone else to see us in those roles as well.”[1]

“She’s Black! Oh, my God!”

In the same vein, the news of the live-action adaptation also garnered a #BlackGirlMagic effect that would have just as much excitement across social media. This is not surprising as there has always been a history of Black audiences wanting to see themselves represented in a way that is not stereotypical, campy, or cliched. However, the move on Disney to celebrate and include a diverse cast is an encouraging move towards embodying the idea of “#RepresentationMatters. Having the teaser trailer center the introduction of Halle Bailey as Ariel makes a strong statement of how narratives can change. Her presence in just the teaser trailer ushers in an opportunity for Black girls to see themselves as magical as well as for other young girls to see a manifestation of what can be beyond the westernized white princess. In Disney’s almost 100-year history there has been only one Black Disney princess — Princess Tiana in “The Princess and the Frog (2009),” which was voiced by Anika Noni Rose. And similar to the casting of Halle Bailey as Ariel, singer Brandy portrayed “Cinderella” in the 1997 made-for-TV film version remake of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. Thus, the addition of the upcoming live-action of The Little Mermaid is very much welcomed.

Evidence of this welcoming was seen in an array of TikTok videos. For many parents, having tangible representations of characters that resemble and look like their children is essential and necessary. In a reaction on TikTok from the Lanier family, it features the three children getting ready to watch The Little Mermaid teaser. Their excitement is captured and is filled with joy (Figure 1.2), “She’s Black! Oh, my God!” exclaimed a wide-eyed Madison (11), followed by their brother Carter (6) shouting “Yes, yes, yes!” with a final reaction from McKenzie (9) “I can’t wait to see this!”

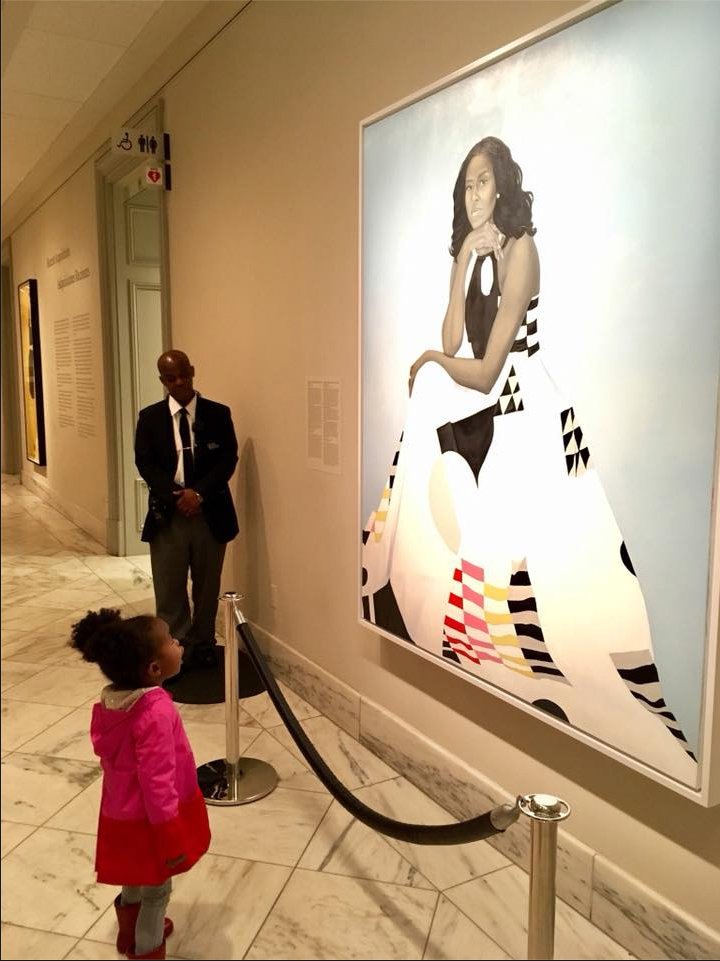

Since the teaser trailer dropped in September 2022, many parents have been flooding the TikTok space with reactions to seeing a Disney princess who looks like them. The reaction to Bailey as Ariel is also very reminiscent of the young Parker Curry’s reaction to the Michelle Obama portrait at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC (Figure 1.3). While the teaser is only a little under one minute and a half, its impact is leaving a long-lasting imprint. With a slow, steady increase of Black girl representation particularly in film and television, The Little Mermaid has the potential to become a part of a legacy that does not diminish Black girl’s imaginations but revitalizes them and makes them a fantastical reality. Even for Bailey, she understands the significance of playing this role, in an interview with Variety magazine she notes, “What that would have done for me, how that would have changed my confidence, my belief in myself, everything…Things that seem so small to everyone else, it’s so big to us.”

Figure 1.6: Parker Curry in awe of seeing the National Portrait Gallery painting of Michelle Obama, Photo credit: Ben Hines

It will be interesting to see how the reactions change or stay the same once the official trailer drops and we visually see the other characters, especially the six other sisters. Since there are seven daughters total, representing the seven seas, the representation of each which is rumored to be from different racial/ethnic backgrounds will be one that probably causes a mix of emotions. Once the rest of the cast is announced and the official trailer is dropped, the conversations will only increase and become even more layered. Moreover, the teaser is an example of a filmic litmus test used to get the ball rolling to see what the response would be and ultimately show people what Halle Lynn Bailey is going to bring to the table as Ariel.

[1] Headlee, C., & Saxena, K. (2022, September 30). Long before 'The little mermaid' remake, Black mermaids were swimming through African folklore. WBUR. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2022/09/30/black-mermaids-the-little-disney

Grace D. Gipson is an assistant professor of African American Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University where she teaches courses on theories and foundations in Africana Studies, Blackness in pop culture, and Black media narratives. Her research interests include Black pop culture, race and gender in comics, Afrofuturism, and digital humanities. Outside the classroom, you can find Grace collecting comic books and stamps on her international travel discoveries, ticket stubs to the latest movies, co-hosting the video podcast "Conversations with Beloved and Kindred," contributing her personal and professional thoughts on pop culture via blackfuturefeminist.com and giving back to the community through a myriad of projects and organizations. You can also follow her on Twitter @GBreezy20 and Instagram @lovejones20.

Bethan Jones is a Research Associate at the University of York. She has written extensively about anti-fandom, media tourism and participatory cultures, and is co-editor of Crowdfunding the Future: Media Industries, Ethics, and Digital Society (Peter Lang) and the forthcoming Participatory Culture Wars: Controversy, Conflict, and Complicity in Fandom (under contract with University of Iowa Press). Bethan is on the board of the Fan Studies Network, co-chair of the SCMS Fan and Audience Studies Scholarly Interest Group and one of the incoming editorial team for the journal Popular Communication.