Bibliography

Bizot, J. F. 2006. Two Hundred trips from the counterculture Graphics and Stories from the Underground Press Syndicate, Thames and Hudson.

Huxley, D. 2001. Nasty Tales: Sex, Drugs, Rock’n’Roll and Violence in the British Underground. Critical Vision.

Huxley, D. (forthcoming) Robert Crumb and the Art of Comics in Worden, D. (ed) The Comics of R. Crumb. University Press of Mississippi.

Huxley, D. 1995: ‘Ceasefire: Women against the War’ in J Walsh (ed) ’The Gulf War Did Not Happen’ Politics, Culture and Contemporary Warfare, Arena.

Sabin, R. 1993. Adult Comics: An introduction, Routledge.

Sabin, R. 2001. Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art, Phaidon. 7

Skinn, D. 2004. Comix: The Underground Revolution. Collins and Brown.

Regional Centres

The rise of several Free Press centres – community presses dedicated to cheap printing for local organisations - allowed for the creation of several regional centres of underground or alternative comic publication.

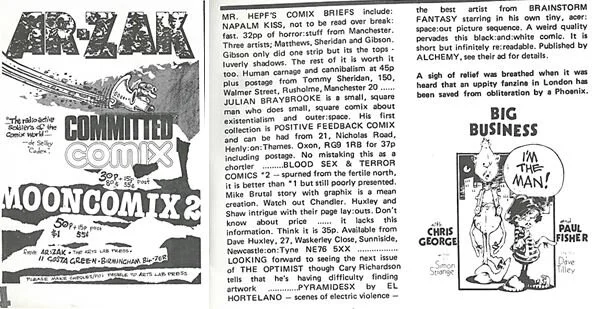

Birmingham: The most significant of these regional centres was Ar:zak in Birmingham. It’s most significant artist was Hunt Emerson, who became a major British underground figure, and also worked for mainstream publications like the BBC’s Radio Times magazine and drew Firkin the Cat for Fiesta magazine. His style was dynamic and easily accessible, and showed the clear influence of American cartoonists. Ar:Zak also featured the work of David Noon, who gave a bold design feel to the comics, which were already probably most graphically sophisticated of UK underground comics at the time.

Figure 11 . David Noon, Street Comix 2, 1976

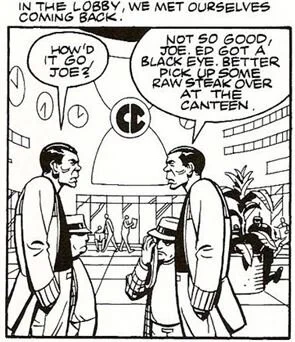

Newcastle upon Tyne: The Junior Print Outfit was the brainchild of comic artist Angus McKie. As well as science fiction cover illustrations and commercial work for publications as diverse as House of Hammer, Metal Hurlant/Heavy Metal, McKie had been published in Cozmic Comics’ Half Assed Funnies. After an accidental meeting at the Tyneside Free Press in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1977 McKie joined forces with Mike Feeney, myself and Alan Craddock to form the Junior Print Outfit, and produced two issues of Either Or Comics. Difficulties with printing and full time jobs restricted output, leading to an A5 four page Neither Nor Comics.

Figure 12 . Neither Nor Comic, 1977

The final publication of the group was Comic Tales, a full colour hardback comic produced in conjunction with Titan books.

Figure 13 . Advertising poster for Comic Tales, 1982

Edinburgh: In 1978 Rob King’s Near Myths featured a range of artists, and most notably Bryan Talbot’s Luther Arkwright. The comic had full colour covers and was well produced, but it only lasted five issues. It also included early work by Grant Morrison.

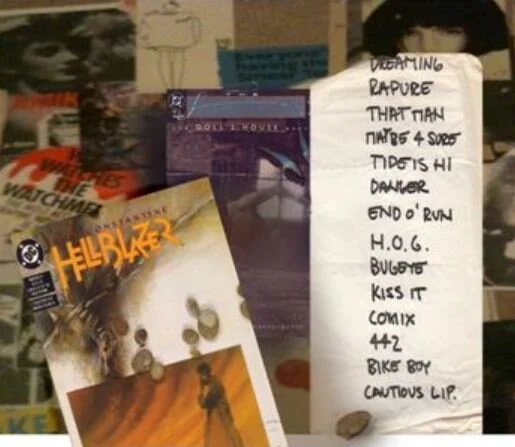

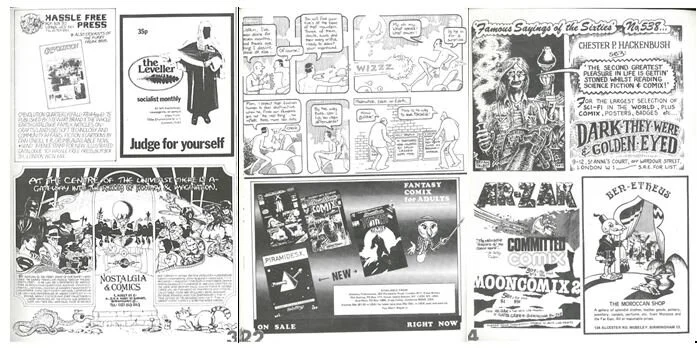

By 1976 there were enough of these groups, and of course London based creators, to organise KAK – the Konvention of Alternative Komics (although notice already the dropping of underground for the more user-friendly alternative). This was followed by KAK 77, with both events organised by Chris Welch and Hunt Emerson. Interest in the field also led Mal Burns to produce Comix Index in 1977, which attempted to list all artists and writers who had appeared in British underground comics up to that point.

Figure 14 . Title page of Comix Index. Caricature of Mal Burns by John Higgins

This publication was invaluable to me when I later undertook a PhD on the subject, completed in 1990, which, with additions and changes, turned into the book Nasty Tales.

Decline

The general increase in interest in comics led the comics historian Denis Gifford to produce Ally Sloper, named after the important nineteenth century English comics character. However the mix of the nostalgic (reprints of work by earlier artists like Terry Wakefield) new work by major contemporary professionals (Frank Hampson and Frank Bellamy) and ‘underground’ artists (Hunt Emerson, Kevin O’Neill) seemed to be to just too diffuse to find an audience, and it only lasted four issues.

Figure 15 . Ally Sloper letterhead, latter to the author, 1976

As Cozmic Comics and Nasty Tales folded by 1975, the final phase of what might be called underground comics in the UK centred again on London, and the more professionally produced Graphixus and Pssst, despite their achievements, became the death throes of the form (although not in mainland Europe, but that is a whole different story). Graphixus was an ambitious title featuring, amongst many others, Brian Bolland, with his work sometimes being controversial, particularly his ‘Little Nympho in Slumberland’ strip. Yet again the comic failed to find a big enough audience, and editor Mal Burns explained its demise;

‘Graphixus, surprisingly enough, was doing better and better. It was actually let down by what was, in retrospect, was an extremely self-indulgent and obscure title. It was actually going to change to High Vision with number seven. The problem was my American distributor going bankrupt on me. I never got paid.’ (interview with the author)

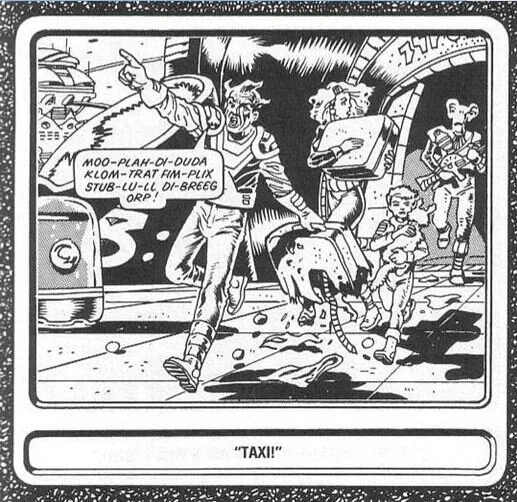

Pssst was the most ambitious of all the later British ‘alternative’ comics. Bankrolled by Frenchman Serge Boissevain, it was also edited by Mal Burns, (and Paul Gravett amongst others). It featured some full colour strips and was vaguely based on similar French adult comic models. Despite a lavish outlay the comic struggled for good distribution and a solid market. It lasted ten issues and finished in 1982, but not before it had published work by veterans like Bryan Talbot, Mike Mathews, all of the Junior Print Outfit and newcomers like Glenn Dakin.3

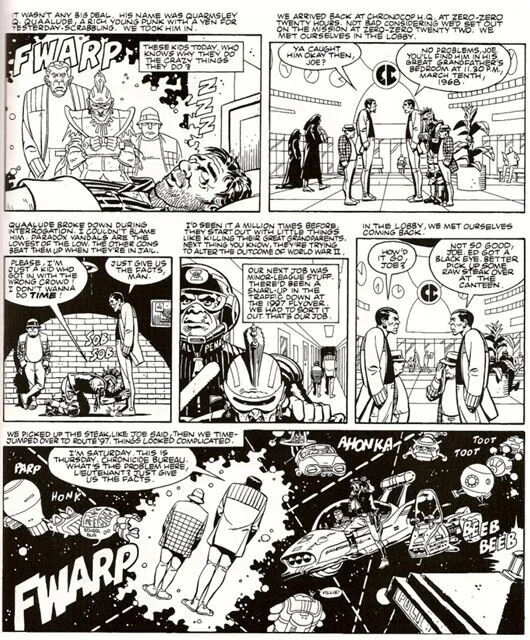

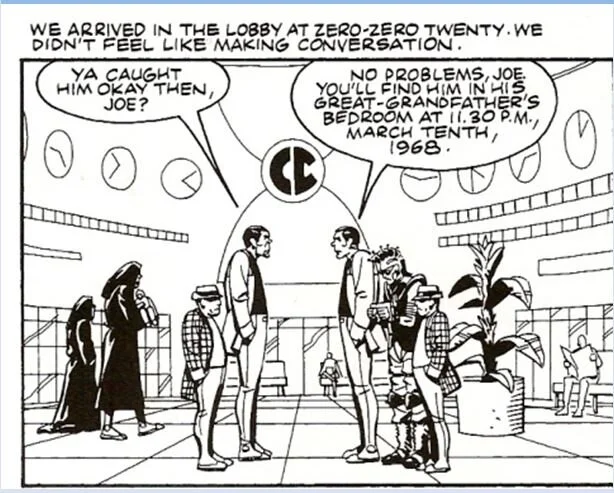

Figure 16. David Huxley, ‘Mike Brutal’, Pssst, 10, 1982

Talbot comments, ‘Pssst was ahead of its time, but it was designed by committee and reputedly lost one hundred thousand pounds. There were five good issues out of ten.’ (interview with the author) The one exception to this decline was Hassle Free Press (an ironic title if ever there was one) which morphed into Knockabout Comics, although they were partially dependant on American material, in particular Gilbert Shelton and Crumb. Tony Bennett at Knockabout survived legal problems to import Crumb’s material, and Knockabout Comics became the home of Hunt Emerson, and published many other underground artists, including Bryan Talbot, Kevin O’Neill and Mike Mathews. History repeated itself in that Knockabout’s censorship problems and customs seizures caused great problems but lead to an outstanding comic in response – The Knockabout Trial Special, in 1984.

Figure 17 . Hunt Emerson, The Knockabout Trial Special, 1984

Legacy

One obvious legacy of British undergrounds was the nurturing of homegrown talent that went on to make significant contributions to comics as a whole (and particularly the US mainstream). Writers Alan Moore and Grant Morrison and artists Brian Bolland, Dave Gibbons and Kevin O’Neill all honed their skills on British undergrounds.

British undergrounds also helped to spread the idea, begun in America, that comics could address a whole range of issues in a whole range of styles. The listing of British underground comics done for my PhD and appearing in Nasty Tales ended in 1982 partially because new ways of producing comics (such as easily accessible and cheap photocopying) made any comprehensive listing impossible. The list, looking back, is woefully inadequate even for the earlier periods. On the other hand these methods, and all the technological advances that followed, mean that small run comics of all kinds are very easy to produce. The underground comics mentioned here provided the inspiration for many later artists. Thus a significant legacy of the underground is that it is possible in many cities across the world to find comics shops that stock a small number of eccentric, unpredictable small publications in amongst the mighty output of DC and Marvel.

Oh yes, I forgot to try and define underground comics, comix, alternative and ground level comics…

Notes

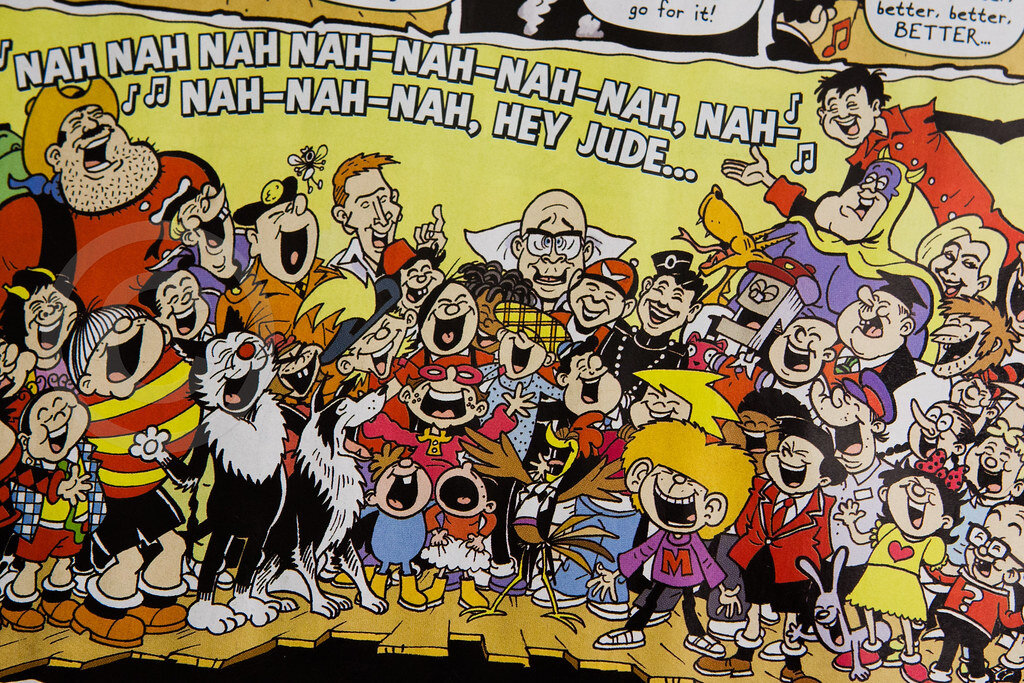

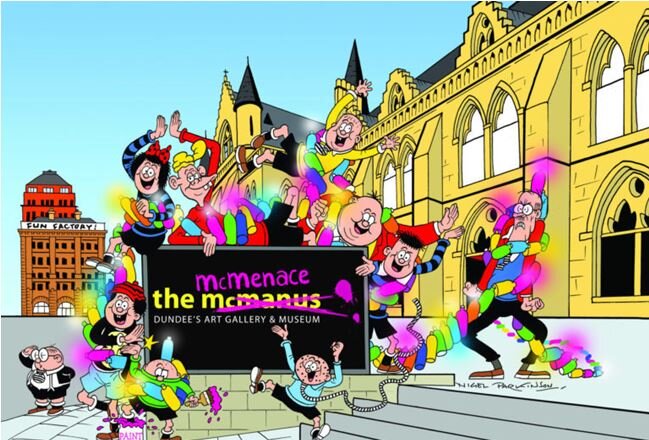

1. Leo Baxendale was the creator of many longstanding British comic characters (mainly for Dundee based D C Thomson) including the Bash Street Kids, Minnie the Minx and Little Plum.

2. As well as the article in Art and Artists, Patricia Dreyfus discussed the impact of the underground on graphic designers in 'The Critique of Pure Funk' in Print, November/December, 1971, p.13.

3. As I drew and wrote comics, does this make me an Aca-Praca-Fan?

Bibliography

Bizot, J. F. 2006. Two Hundred trips from the counterculture Graphics and Stories from the Underground Press Syndicate, Thames and Hudson.

Huxley, D. 2001. Nasty Tales: Sex, Drugs, Rock’n’Roll and Violence in the British Underground. Critical Vision.

Huxley, D. (forthcoming) Robert Crumb and the Art of Comics in Worden, D. (ed) The Comics of R. Crumb. University Press of Mississippi.

Huxley, D. 1995: ‘Ceasefire: Women against the War’ in J Walsh (ed) ’The Gulf War Did Not Happen’ Politics, Culture and Contemporary Warfare, Arena.

Sabin, R. 1993. Adult Comics: An introduction, Routledge.

Sabin, R. 2001. Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art, Phaidon.

Skinn, D. 2004. Comix: The Underground Revolution. Collins and Brown.

David Huxley is the editor of The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (Routledge). He was a senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University until 2017. He has written widely on comics, including works on various artists, underground and horror comics, superheroes and also popular film. He has also drawn and written for a range of British comics, including Ally Sloper, Either or Comics, Pssst, Oink and Killer Comics. His most recent publication is Lone Heroes and the Myth of the American West in Comic Books 1945-1962 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2018).