EMMYS WATCH 2024 – Curbeth Thou Enthusiasm: Is Larry David a 21st Century Shakespearean Fool?

/This post is part of a series of critical responses to the shows nominated for Outstanding Drama Series and Outstanding Comedy Series at the 76th Emmy Awards.

“Sirrah, you were best take my coxcomb” (King Lear, Act 1, Scene 4).

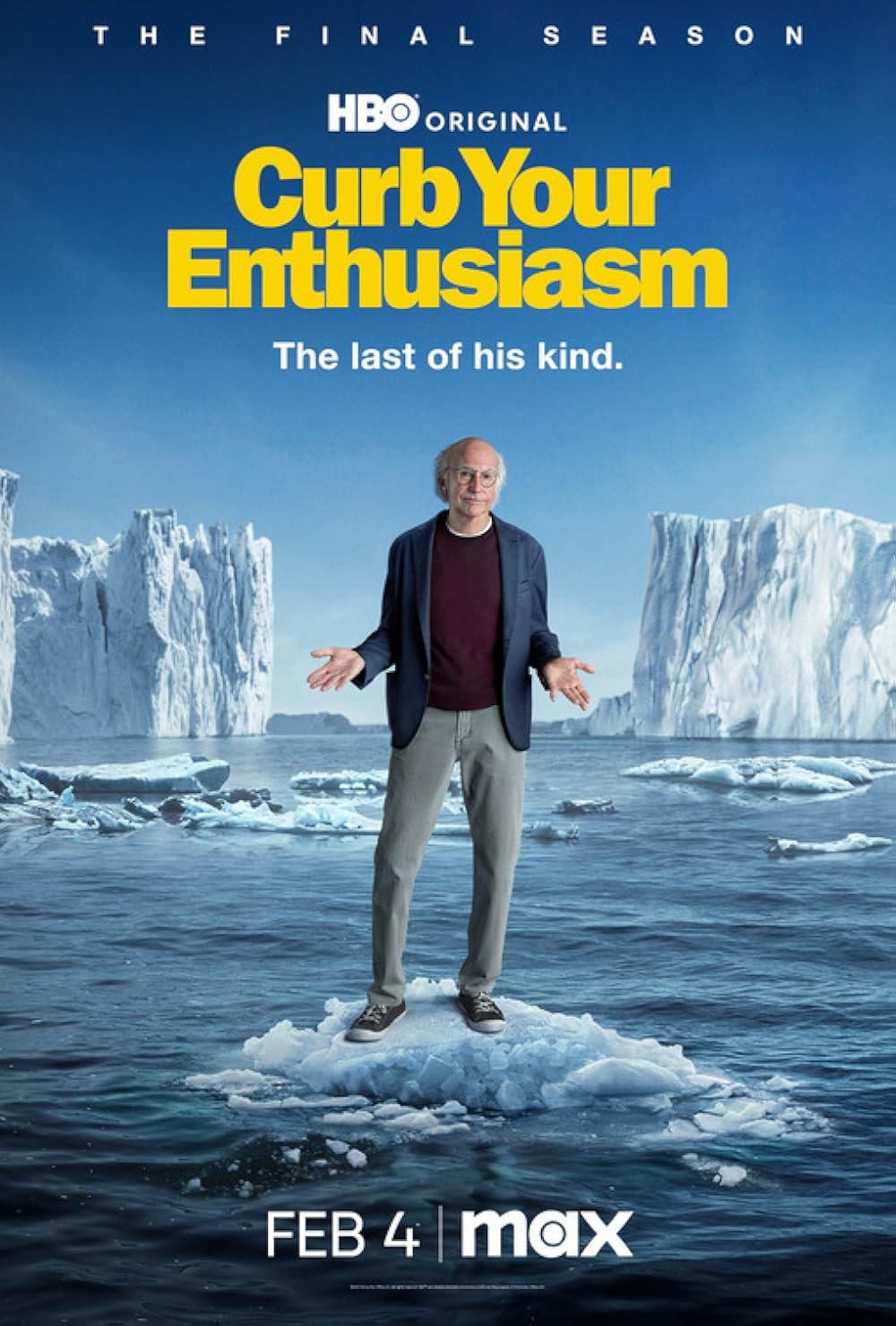

The 2024 Emmy Awards marks the end of an era in the nominations of Curb Your Enthusiasm (HBO/Max, 2000-2024) for its final season in the following categories: Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series (Larry David), Outstanding Casting In A Comedy Series (Allison Jones), Outstanding Sound Mixing For A Comedy or Drama Series (Half-Hour) (Earl Martin, Chuck Buch, Trino Madriz, and Sam C. Lewis), and Outstanding Comedy Series (Producers: Larry David, Jeff Garlin, Jeff Schaffer, Laura Streicher, Jennifer Corey, and Adam Feil). The series depicts cringey encounters and situations of former Seinfeld writer/producer Larry David (a fictionalized version of himself) as he endeavors to simply exist among his peers and their friends in Los Angeles. Curb Your Enthusiasm (and arguably Larry David himself) holds a unique place in television and cultural history; this series came on the heels of the multi-cam sitcom sensation, Seinfeld (of which Larry was co-creator/ writer) at a time when reality television was gaining significant traction. Although not quite mockumentary in style, Curb Your Enthusiasm skillfully plays with real-world conjunctures and Larry David not only holds a mirror (as most comics do) to our inner biases and repressed judgments, he shakes-out our cultural norms, puts them on a big flag, and runs around waving it our face like the finale of Act One in Les Misérables. Much can be written about Curb Your Enthusiasm in terms of form, production, and comedy writing more generally. However, in this piece I want to take the opportunity to frame and pose a question with which I’ve been grappling. When teaching media history to my students, I inevitably find myself contextualizing much of television performance, writing, and character in terms of Shakespeare’s works. I am acutely aware that my theatre background lends me to this position; I am drawn to Shakespeare’s joint use of wordplay with situation in heightening the stakes for both drama and comedy. Therefore, when I reflect on the last quarter century of Curb Your Enthusiasm, I see this long running comedy through lens of Shakespeare’s plays; or rather, I see Larry David as a Shakespearean clown: The Fool from King Lear, Bottom from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, or Touchstone from As You Like It. Like these characters, he states uncomfortable truth, finds himself in akward situations, and wryly comments on the absurdities of life. Also like these characters, who don’t incur the wrath of their superiors in the plays (or the audience), Larry David manages to squeak past mass criticism and controversy despite his uncouth comedy. What makes Larry David different than other comics in that he is essentially as safe as the “Shakespearean clown?”

First, let’s get from Shakespearean characters/theatre to an HBO (or rather, Max – enter Amanda Lotz (2018) on the ever-shifting and continual consolidation of media companies) television show and quickly move through 500 years of Shakespearean influence on the masses. As a media and pop-culture researcher, I am interested in how certain art forms and platforms shift and transpire according to various historical conjunctures and the ways these art forms encompass a broad audience and impact “ordinary” culture (Williams, 1958). Shakespeare wrote his plays for a diverse audience. From the groundlings, made-up of the common folk, to Queen Elizabeth I (and later the King James), his plays transcended social and cultural boundaries. Historical scholar, Levine (1990), who wrote on the changing cultural status of Shakespeare in early nineteenth century America, explains that “the theatre, like the church, was one of the earliest and most important cultural institutions established in frontier cities. And almost everywhere the theater blossomed Shakespeare was a paramount force” (Levine, 1990, p. 18). Initially, there was a common and intimate knowledge that average Americans had of Shakespeare (Levine, 1990), and therefore his characters – such as the fool – were broadly present and understood. It wasn’t until the transformation that occurred during the end of the nineteenth century into the beginning of the twentieth century where, for Americans, the “theater no longer functioned as an expressive form that embodied all classes within a shared public space” (Levine, 1990, p.68). From then on, theatre (and by default, Shakespearean plays) transitioned away from the masses and was reserved for those wealthy enough to purchase tickets. Cue Bourdieu’s (1984) Distinction. A century later, we can identify screen media as the platform that provides a more democratizing access to entertainment (anyone else watch the Eras Tour on Disney+ instead of paying over $500 for tickets like many of my undergrads did?). There is, of course, still a monetary hurtle to access various streaming services, albeit less than tickets to live theatre. All this to say, HBO/Max sits somewhere in the middle as it was still a paid cable station when Curb Your Enthusiasm began its run in 2000 and has grown in popularity in recent years due to the surge in streaming platforms’ successful proliferation. Therefore, Larry David’s reach and influence on viewers and culture is noteworthy.

Curb Your Enthusiasm falls into a vast canon of centuries of tradition where pop culture uses humor to skillfully address our personal and societal flaws. In this way, Larry David has been “The Fool” to the audience’s “King Lear.” Shakespeare utilizes the character of “The Fool” (this is true for Touchstone in As You Like It) to critique the king, draw attention to his faults, and call him out on his misjudgments. This was often the role of fools in the royal court; under the guise of humor, the fool or court jester was allowed to (as they say) speak truth to power. So, while The Fool in King Lear is speaking to Lear in the context of the play, The Fool is also speaking to the audience in his narration and critique of the King’s errors. Now, The Fool is “punching up” when he blasts the king, which in comedy means he is making fun of those of a higher status. When you are a fool in a royal court you can only punch up. Comics tend to come under scrutiny when they “punch down” on different identities. Larry has seemingly found a way to make-fun of identities and situations that should in theory be off-limits to anyone wanting to avoid being canceled. Jerry Seinfeld and Dave Chapel are prime examples of comics who have recently come under serious scrutiny for questioning and/or pushing comedy to tackle sensitive and polarizing topics. Certainly, there is much to unpack regarding why these comics’ crossed boundaries for some audiences, but the fact remains that Larry David’s remains largely unscathed.

One reason could be that he is so likeably unlikeable. Much like Bottom from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the audience forgives Larry David for his oblivion to social norms because the comedy that ensues is worth it, and his ignorance is far more innocent than sinister. As a plot point, and not so subtle metaphor, Bottom falls victim to a fairy-spell that transforms his head to that of an ass. Larry David is also - to put it bluntly - an ass. In one episode he picks up a sex-worker so he can beat the LA traffic by driving in the carpool lane, and in another he uses the handicap bathroom stall and justifies it by pretending to have a stutter.

But, he is also often wrongly accused of being an ass, when the situation just rolls out of control; he is caught in possession of a Black lawn jockey statue, but only because he needed to replace the one that he broke at a southern Air B&B where he was staying. Once he was kicked out of a hot yoga class for not saying namaste. Another possible reason he gets away with political incorrectness is that he is also the butt of many of his own jokes. Touchstone in As You Like It is full of dry wit, self-deprecation, and a hint of neurosis. This court jester who expresses cynicism through comedy as he comments on human interaction and the absurdity of social norms for the benefit of the audience is endearing. Such an outlook is essentially the theme that underpins every episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. In addition to this, Larry David’s friends and family (with maybe only the exception of Jeff Green (Jeff Garlin) and Leon Black (JB SMOOVE)) admonish and baulk at his behavior. Perhaps, for the audience, this is enough retribution? The other characters can take on the role of human decency, and this allows the audience to laugh and relish in Larry David’s inappropriateness.

Curb Your Enthusiasm spans 12 seasons over 25 years. I wrote my dissertation on Law & Order: SVU, so I am a little too familiar with shows that run for multiple decades and address changing cultural landscapes. Unlike Seinfeld, which sits statically as a landmark piece of 90s television, Curb Your Enthusiasm absorbed cultural moments over a more expansive period. Or rather, Curb Your Enthusiasm actively dismantled the respect and reverence for serious historical incidents: At a dinner party, Larry (unawares) introduces two “survivors” to bond - one is a Holocaust survivor, and one is a contestant from the TV show, Survivor. Larry and his wife Cheryl (Cheryl Hines) took in the Blacks, a family of refugees from Hurricane Katrina, and Larry pointedly states to them, “You’re Black and your last name is Black. That’s like if my name was Larry Jew.” He incurred the wrath of Ayatollah Khomeini for announcing his intention to write a musical comedy called “Fatwa.” In the season directly following Me Too, Larry and the woman he was hooking-up with film their entire sexual exchange while loudly consenting in an over-the-top manner. And then there is the Palestinian chicken restaurant episode (Season 8, episode 3)… which no summary could really do justice. From Seinfeld, famously a show about nothing, Curb Your Enthusiasm is a show about … everything.

But now that we have reached the end, where will Curb Your Enthusiasm land in the context of pop-culture comedy history, and will it hold up? Feinberg (2024) states, “in a world in which social media has made us into a nation of Larry Davids platforming everybody’s microaggressions, Curb Your Enthusiasm didn’t have a place anymore.” I am not sure I fully agree, but it certainly is an interesting point. With the evolving and shifting space for performance, from theatre, to television, to social media, where does the Shakespearean fool currently reside? Feinberg implies that anyone with a gripe on Tik-Tok fills this void. Regardless of social media’s democratization and amplification of public voices, I think there is still a role reserved for designated court jesters, or at the very least, court jesters in scripted media. Larry David did more than just “platform microaggressions;” he took big risks with his social commentary and did so for a large, designated audience. Shakespeare’s relevance transcends centuries, and this longevity (along with the cultural shifts that relegated it to a higher status) is what immortalizes and pedestals his work. I wouldn’t be surprised if Larry David’s work will stand the test of time, especially as only his show, not him, is currently “canceled” (maybe we all just loved his Bernie Sanders impression too much). Going forward, I am sure new Shakespearean fools’ voices will emerge. Curb Your Enthusiasm may not always be culturally relevant, but like Shakespearean themes on humanity, Larry David’s display and comment on social annoyance, will most likely continue to ring “pretty, pretty, pretty” true.

Works Cited

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Levine, L. (1990) Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Lotz, A. D. (2018). We Now Disrupt This Broadcast: How Cable Transformed Television and the Internet Revolutionized it All. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Williams, R. (1958). “Culture is Ordinary.” Raymond Williams on Culture & Society: Essential Writings, edited by Jim McGuigan. Sage Publishers, 1-18.

Biography

Lauren Alexandra Sowa is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Communication at Pepperdine University. She recently received her Ph.D. from the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. Her research focuses on intersectional feminism and representation within production cultures, television, and popular culture. These interests stem from her several-decade career in the entertainment industry as member of SAG/AFTRA and AEA. Lauren is a proud Disneyland Magic Key holder and enthusiast of many fandoms.