The "Creative Child" Meets The "Digital Native": An Interview with Amy F. Ogata (Part Two)

/You write extensively in the book about the design of playrooms, suggesting that there is a shift in terms of children’s access to physical space within the home during this period. What factors led to the shift and what were the prevailing ideas about the design of play spaces for children?

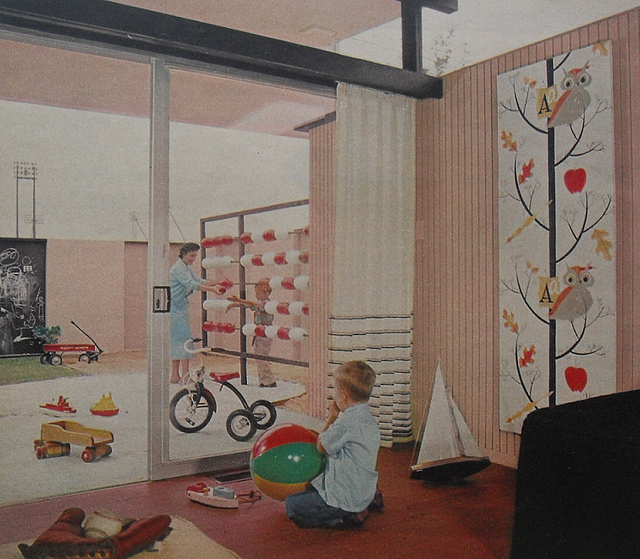

Yes, I spent a lot of time thinking not only about playrooms and playhouses of the domestic sphere, but also public schools and museums. In the single-family dwelling, the shift I am trying to trace is the growing belief that children, whose numbers exploded in the U.S. after World War II, needed their own spaces and that these were not just utilitarian leftover spaces but rather specially designed to promote their imaginations. In architect-designed houses, there were often playrooms on the plans. Even in builder houses, there were special places indicated for children's activities. One of the main ideas was that children should have "correctly" outfitted spaces. The American Toy Institute commissioned a series of model playrooms to house numerous toys and make playing indoors attractive. Others, such as the anthropologist Margaret Mead argued that children should be left alone in their bedrooms to think and develop their own ideas. Isolation is one of the themes but proximity to the rest of the family, especially the mother, is also written into some of these houses. And the making of a "creative" home environment was stated in magazines and guidebooks as an expectation of postwar parents.

As you note, there was a dramatic increase in the number of children’s museums across this period, as well as a changing philosophy about what forms of creative engagement such museums should support. What has been the lasting impact of these ideas on current museum practices?

The form children's museums take today is, in part, a result of the enduring notion that the sensory encounter of objects will enhance learning and stimulate new thoughts. Children's museums as a type were not new, but they did increase very quickly during the Baby Boom. And while early museums emphasized nature study, their postwar versions were more likely to ask the child to experience something, whether it was being under a city street or climbing through a giant molecule. In the case of the Exploratorium, which was never specifically a children's museum but engaged lots of children, visitors were encouraged to experiment with perception. Several museums I discuss look very different today--the Exploratorium, for example, has just moved to a new facility--they now attract a much younger child than museums in the 60s and 70s, and many of the exhibits are less open-ended or they go straight for entertainment, emphasizing dramatic play over, say, studying waves in a ripple tank. I think the most long-lasting aspect is the general belief that children should be active in the museum space.

It seems to me that some contemporary efforts to develop alternative kinds of spaces for children and youth still owe a great deal to the design approaches of this era. I was hoping I might get you to comment on what someone from the 1960s would recognize or find strange about two contemporary educational spaces for children? The first is the YouMedia Center at the Chicago Public Library.

Sounds like a great space and in some ways it resembles the kinds of open school ideas of the late 60s and 70s. In that age, the push for large open spaces and team teaching was promoted as an answer to a teacher shortage, and to enable use of "teaching machines" and media (in that day it was film, television and sound recording), and a way of engaging children in hands-on projects, like producing TV shows for their schools. While architects thought that the spaces they created would ensure that teachers and students behaved in certain ways--smaller classrooms would encourage small group instruction, larger spaces might promote collaborative projects, moveable furniture would lead to flexible spaces--however, that didn't necessarily happen. YouMedia is obviously not a space where core subjects are taught on a daily basis, but instead is an auxiliary space for exploration after school, perhaps more like the Exploratorium or the Brooklyn Children's Museum as it was a long time ago. There, children and teens could operate machines, mix soils in a greenhouse, graffiti a concrete wall, or retreat to read in a library housed in a leftover gas tank.

The second is the Los Feliz Charter School for the Arts. Again, what commonalities and differences do you see between the ideal creative spaces of the 1960s and this school?

This is another great example of the ways that progressive educational ideas are resurgent, however, this is a charter school with access to the kind of private funding that is not available to regular public schools that depend on tax revenue. The schools I discuss were all publically funded (some were in extremely wealthy neighborhoods and others in poor rural areas) and aimed to accomplish some (but certainly not all) of these same learning objectives. Many of them were small and have been changed over the years. It seems that the Los Feliz school has tried to use space to encourage curricular outcomes. Like some schools in the postwar era they have given over far more teaching space to projects like art, music and drama. Increasingly these are the subjects that are getting squeezed out of the public school day by constant budget cuts, emphasis on standardized testing, and in places like New York City, by demands on limited space. The sentiment that one teacher in this video conveys--that they are not trying to turn out artists but rather confident, well-balanced people--echoes exactly the discourse on creativity in the postwar years. The notion that creativity is a lifelong benefit that will eventually help children become competitive in the workplace has also found its way to college campuses. I don't mean to sound skeptical of creativity itself (I am an art historian!), but I think that the schemes we adopt to instrumentalize it reveal that we lionize creativity as a cultural myth at moments when we feel insecure.

Amy F. Ogata is associate professor at the Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture in New York City. She is the author of Art Nouveau and the Social Vision of Living. Her new book, Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America was recently published by the University of Minnesota Press.