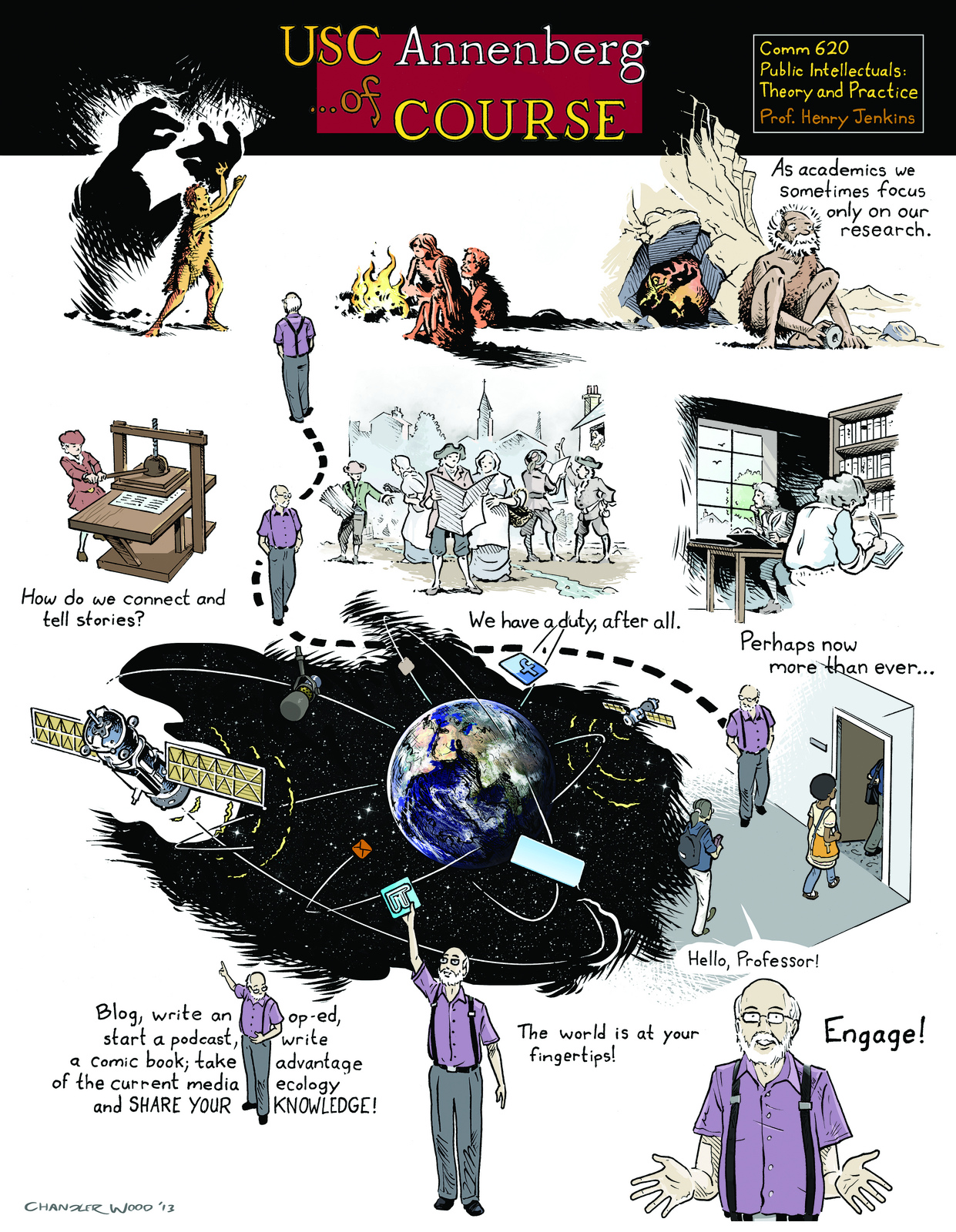

Last time, I shared the syllabus for a new course I am offering this fall focused on, basically, "how to be a public intellectual." Today, I am sharing the syllabus for the other class I am teaching this term. I have taught Transmedia Entertainment three times since coming to USC, each time I have more or less had to re-imagine and redesign the class to reflect shifts in media practice and especially the expanding body of scholarship about transmedia. You can see my first and second versions of the class as I shared them through earlier blog posts. You will see that recent scholarly publications have resulted in much richer models for thinking about the economic and cultural impact of the current franchise structure, the distinctive nature of "media mix" in Japan as a point of comparison with the ways transmedia has taken shape in Hollywood, and the nature and function of world-building. Alongside this class, I am going to be featuring in my blog this fall a series of interviews with the authors of many of these new books, starting soon with an in-depth exchange with Mark J. P. Wolf, author of Building Imaginary Worlds. As always, I am taking advantage of my Los Angeles location to bring into my classroom a rich array of guest speakers who are doing some of the cutting edge experimentation around transmedia.

Transmedia Entertainment

We now live in a moment where every story, image, brand, and relationship plays itself out across the maximum number of media platforms, shaped top down by decisions made in corporate boardrooms and bottom up by decisions made in teenagers’ bedrooms. The concentrated ownership of media conglomerates increases the desirability of properties that can exploit “synergies” among different parts of the medium system and “maximize touchpoints” with different niches of audiences. The result has been a push toward franchise-building in general and transmedia entertainment in particular.

A transmedia story represents the integration of entertainment experiences across a range of media platforms. A story like Heroes or Lost might spread from television into comics, the web, alternate reality or video games, toys, and other commodities, etc., picking up new audiences as it goes and allowing the most dedicated fans to drill deeper. The fans, in turn, may translate their interests in the franchise into concordances and Wikipedia entries, fan fiction, vids, fan films, cosplay, game mods, and a range of other participatory practices that further extend the story world in new directions. Both the commercial and grassroots expansion of narrative universes contribute to a new mode of storytelling, one which is based on an encyclopedic expanse of information which gets put together differently by each individual, as well as processed collectively by social networks and online knowledge communities.

Each class session will introduce a concept central to our understanding of transmedia entertainment that we will explore through a combination of lectures, screenings, and conversations with industry insiders who are applying these concepts through their own creative practices.

In order to fully understand how transmedia entertainment works, students will be expected to immerse themselves in at least one major media franchise for the duration of the term. You should experience as many different instantiations (official and unofficial) of this franchise as you can and try to get an understanding of what each part contributes to the series as a whole.

REQUIRED BOOKS

- Derek Johnson, Media Franchises: Creative Licensing and Collaboration in the Creative Industries (New York: New York University Press, 2013)

- Andrea Phillips, A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012)

- Michael Saler, As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011)

- Mark J. P. Wolf, Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (London: Routledge, 2013)

All additional readings will be provided through the Blackboard site for the class.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL RESPONSE

For the first assignment, you are asked to write a 5-7 page autobiographical essay describing your relationship to a media franchise that you have found to be personally meaningful. You should use this essay to identify the cultural attractors that drew you to this franchise, to discuss which variants of the franchise you experienced, and to describe any cultural activators that encouraged you to more actively contribute to the fan community surrounding this franchise. Be as specific as possible in discussing moments in the transmedia story that were especially important in shaping your engagement with the property. Where possible, make explicit reference to ideas about transmedia and engagement from the readings. This assignment is partially about getting to know you as a transmedia participant and partially about getting you to experiment with the critical vocabulary we’ve introduced so far for talking about transmedia experiences. (Due September 23) (20 Percent)

EXTENSION PAPER

Write a 5-7-page essay examining one commercially produced story (comic, website, game, mobisode, amusement park attraction, etc.) that acts as an extension of a “core” text (for instance, a television series, film, etc.). You should try to address such issues as its relationship to the story world, its strategies for expanding the narrative, its deployment of the distinctive properties of its platform, its targeted audience, and its cultural attractors/activators. The paper will be evaluated on its demonstrated grasp of core concepts from the class, its original research, and its analysis of how the artifact relates to specific trends impacting the entertainment industry. Where possible, link your analysis to the course materials, including readings, lecture notes, and speaker comments. (Due October 25) (20 Percent)

FINAL PROJECT – FRANCHISE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT

Students will be organized into teams, which—for the purpose of this exercise—will function as transmedia companies. You should select a media property (a film, television series, comic book, novel, etc.) that you feel has the potential to become a successful transmedia franchise. In most cases, you will be looking for a property that has not yet added media extensions, though you could also look at a property that you feel has been mishandled in the past. You should have identified and agreed on a property no later than Sept. 13th. By the end of the term, your team will be “pitching” this property. The pitch should include a briefing book that describes:

- the defining properties of the media property

- a description of the intended audience(s) and what we know of its potential interests

- a discussion of the specific plans for each media platform you are going to deploy

- an overall description for how you will seek to integrate the different media platforms to create a coherent world

- parallel examples of other properties which have deployed the strategies being described

For a potential model for what such a book might look like, see the transmedia bible template from Screen Australia, available here: http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/filmmaking/digital_resources.aspx. Or visit: http://zenfilms.typepad.com/zen_films/2010/06/transmedia-workflow.html. If you use either as a model, include only those segments of their bible templates that make sense for your particular property and approach. You can also get insights on what a bible format might look like from the Andrea Phillips book.

The pitch itself will be a group presentation, followed by questions from our panel of judges (who will be drawn from across the entertainment industry). The length and format of the presentation will be announced as the term progresses to reflect the number of students actually involved in the process and thus the number of participating teams. The presentation should give us a “taste” of what the property is like, as well as lay out some of the key elements that are identified in the briefing book. Each team will need to determine what the most salient features to cover in their pitches are, as well as what information they want to hold in reserve to address the judge’s questions. Each member of the team will be expected to develop expertise around a specific media platform, as well as to contribute to the overall strategies for spreading the property across media systems.

The group will select its own team leader, who will be responsible for contact with the instructor/TA and who will coordinate the presentation. The team leader will be asked to provide feedback on what each team member contributed to the effort, while team members will be asked to provide an evaluation of how the team leader performed. Team members will check in with the TA on Week Six and with Prof. Jenkins on Week Ten and Week Thirteen to review their progress on the assignment. The instructor may request short written updates throughout the term to insure that the team is moving in the right direction.

Students will pitch their ideas to the panel of judges on December 2. They should expect to receive feedback from the instructor over the following few days, and then turn in the final version of their written documentation on the exam date scheduled for the class. (40 percent)

CLASS FORUM/PARTICIPATION

For each class session, students will be asked to contribute a substantive question or comment via the class forum on Blackboard. Comments should reflect an understanding of the readings for that day, as well as an attempt to formulate an issue that we can explore with visiting speakers. Students will also be evaluated based on regular attendance and class participation. (20 Percent)

Week 1, Monday, August 26

Transmedia Storytelling 101

- Henry Jenkins, “Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling,” Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), pp. 93-130.

- Henry Jenkins, “Transmedia Storytelling 202: Further Reflections,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, August 1, 2011,

- Nick DeMartino, “Why Transmedia Is Catching On Now,” Future of Film Blog, July 5-7, 2011. Part Two. Part Three.

- Mark J. P. Wolf, “Transmedial Growth and Adaptation,” Building Imaginary Worlds (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 245-267.

Speaker: Geoffrey Long

Geoffrey Long is a media analyst, scholar, and storyteller exploring transmedia experiences, emerging entertainment platforms, and the future of entertainment. He is an alum of the MIT Comparative Media Studies program, a fellow with the Futures of Entertainment community, and a co-editor of the Playful Thinking book series from the MIT Press. He previously served as Lead Narrative Producer for the Narrative Design Team at Microsoft Studios. Find more at geoffreylong.com.

Week 2, Monday, September 2

No Class: Labor Day

Week 3, Monday, September 9

A Brief History of Transmedia

- Henry Jenkins, “Transmedia: A Prehistory,” in Denise Mann (ed.), Wired TV (Work in Progress)

- Michael Saler, “Living in the Imagination,” “Delight Without Delusion: The New Romance, Spectacular Texts, and Public Spheres,” As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 25-104.

- J.P. Telotte, Disney TV (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004), pp. 61–79.

- Justin Wyatt, “Critical Redefinition: The Concept of High Concept,” High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1994), pp. 1-22.

- Jonathan Gray, “Learning to Use the Force: Star Wars Toys and Their Films,” Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: NYU Press, 2010), pp. 177-187.

Students will meet in their teams for the first time.

Friday, September 13

Teams should have picked media franchise

Week 4, Monday, September 16

Transmedia Engagement

- Christy Dena, “Emerging Participatory Culture Practices: Player-Created Tiers in Alternate Reality Games,” Convergence, February 2008, pp. 41-58.

- Ivan Askwith, “Five Logics of Engagement,” Television 2.0: Reconceptualizing TV as an Engagement Medium, Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2007, pp. 51-150.

- Sam Ford, “True Blood Case Study” (Work in Progress)

- Andrea Phillips, “The Four Creative Purposes for Transmedia Storytelling,” “Interactivity Creates Deeper Engagement,” “Uses and Misuses for User-Generated Content,” “Challenging the Audience to Act,” and “Make Your Audience a Character, Too,” A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 41-54, 110-126, 137-148, 149-182..

- (Rec.) Ivan Askwith, “Deconstructing the Lost Experience,” Convergence Culture Consortium white paper,

Week 5, Monday, September 23

The Japanese Media Mix

- Otsuka Eiji, “World and Variation: The Reproduction and Consumption of Narrative,” Mechademia 5, 2010, pp. 99-116.

- Marc Steinberg, “Media Mixes, Media Transformations,” Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012).

- Ian Condry, “Characters and Worlds as Creative Platforms,” The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013).

- Mizuko Ito, “Gender Dynamics of the Japanese Media Mix,” in Yasmin B. Kafai, Carrie Heeter, Jill Denner, and Jennifer Y. Sun (eds.), Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), pp. 97-110.

Autobiographical response due

Speaker: Aaron Koblin

Aaron Koblin is an artist and designer specializing in data and digital technologies. Aaron's work takes real-world and community-generated data and uses it to reflect on cultural trends and the changing relationship between humans and the systems they create. His work is part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. His projects have been shown at international festivals including TED, Ars Electronica, SIGGRAPH, OFFF, and the Japan Media Arts Festival. He received the National Science Foundation's first place award for science visualization and two of his music video collaborations have been Grammy nominated. He received his MFA in Design|Media Arts from UCLA. In 2010 Aaron was the Abramowitz Artist in Residence at MIT and he leads the Data Arts Team in Google's Creative Lab.

Week 6, Monday, September 30

Transmedia Learning

- Meryl Alper and Becky Herr-Stephenson, “T is for Transmedia,” Joan Ganz Cooney Center and Annenberg Innovation Lab white paper.

TA meets with franchise development teams to review progress.

Speaker: Erin Reilly

Erin Reilly is Creative Director for Annenberg Innovation Lab and Research Director for Project New Media Literacies at USC's Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism. Her research focus is children, youth and media and the interdisciplinary, creative learning experiences that occur through social and cultural participation with emergent technologies. Having received multiple awards, such as Cable in a Classroom’s Leaders in Learning, she is most notably known for co-creating one of the first social media citizen science programs, Zoey's Room. Her current projects include PLAY!, a new approach to professional development that refers to the value of play as a guiding principle in the educational process to foster participatory learning and The Mother Road, a chance to explore collective storytelling through the development of the Evocative Places eBook series. Erin consults with private and public companies in the areas of mobile, creative strategy and transmedia projects for children.

Week 7, Monday, October 7

The Franchise System

- Derek Johnson, “An Industrial Way of Life,” “Imagining the Franchise: Structures, Social Relations, and Cultural Work,” “From Ownership to Partnership: The Institutionalization of Franchise Relations,” Media Franchises: Creative Licensing and Collaboration in the Creative Industries (New York: New York University Press, 2013), pp. 1-106.

- Sam Ford, “Glee Case Study” (Work in Progress).

Week 8, Monday, October 14

Producing Transmedia

- Brian Clark, “Transmedia Business Models,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, November 7, 2011

- Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, “Courting Supporters for Independent Media,” Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2013), pp. 229-258.

- Henry Jenkins et al., “Kickstarting Veronica Mars: A Conversation about the Future of Television," Confessions of an Aca-Fan, March 26-29, 2013, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four

- Andrea Phillips, “How to Fund Production Costs,” “And Maybe Make Some Profit, Too,” A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 223-239..

Speaker: Andrea Phillips

Andrea Phillips (born 20 July 1974) is an American transmedia game designer and writer. She has been active in the genres of transmedia storytelling and alternate reality games (ARGs), in a variety of roles, since 2001. She has written for, designed, or substantially participated in the creation of Perplex City, the BAFTA-nominated Routes (a project of Channel 4), and The 2012 Experience, a marketing campaign for the film 2012. Phillips came to the genre in 2001, when she co-moderated the Cloudmakers mailing list, which served players of "The Beast", the ARG which revolved around the release of the movie A.I. Artificial Intelligence. Phillips in 2012 published A Creator's Guide to Transmedia Storytelling as a guide for current and aspiring modern storytellers.

Week 9, Monday, October 21

No Class: Meet with your teams

Friday, October 25

Extension Paper Due

Week 10, Monday, October 28

World Building

- Derek Johnson, “Sharing Worlds: Difference, Deference, and the Creative Context of Franchising,” Media Franchises: Creative Licensing and Collaboration in the Creative Industries (New York: New York University Press, 2013), pp. 107-152..

- Mark J. P. Wolf, “World Structures and Systems of Relationships,” Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (London: Routledge, 2013), pp.153-197.

- Michael Saler, “The Middle Positions of Middle Earth: J.R.R. Tolkien and Fictionalism,” As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 158-196.

- Henry Jenkins, “The Pleasure of Pirates and What It Tells Us about World Building in Branded Entertainment”, Confessions of an Aca-Fan, June 13, 2007

- If you have not already done so, please try to watch Oz, the Great and Powerful before this class session.

Prof. Jenkins check-in with teams

Speaker: Alex McDowell

Alex McDowell is one of the most innovative and influential designers working in narrative media today, with the impact of his ideas extending far beyond his background in cinema. McDowell advocates for an immersive design process that acknowledges the key role of world building in visual storytelling. Since moving to Los Angeles from London in 1986, McDowell has designed for directors as diverse as Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton, David Fincher, Zack Snyder and Steven Spielberg. Currently McDowell is production designer for Man of Steel with director Zack Snyder, produced by Chris Nolan. He recently completed In Time, directed by Andrew Niccol. With many awards for his film design work, McDowell was named a Royal Designer by the UK’s Royal Society of Arts in 2006. McDowell, who currently serves on the AMPAS SciTech Council, recently joined the faculty of the School of Cinematic Arts, where he will teach across several of the SCA divisions focusing on the role of world-building in the cinematic process. McDowell is co-founder and creative director of 5D | The Future of Immersive Design, a global series of distributed events and an education space for an expanding community of thought leaders across narrative media.

Week 11, Monday, November 4

Continuity and Multiplicity

- William Uricchio and Roberta E. Pearson, “I’m Not Fooled by That Cheap Disguise,” in Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (eds.), The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to A Superhero and His Media (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 182-213.

- Sam Ford and Henry Jenkins, “Managing Multiplicity in Superhero Comics,” in Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (eds.), Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), pp. 303-313.

- Shawna Kidman, “Five Lessons For New Media From the History of Comics Culture,” International Journal of Learning and Media 3.4 (2012): 41-54.

Speaker: Corniela Funke

During the late 1980s and the 1990s, Corniela Funke established herself in Germany with two children's series, namely the fantasy-oriented Gespensterjäger (Ghosthunters) and the Wilde Hühner (Wild Chicks) line of books. Funke has been called "the J. K. Rowling" of Germany. The first of her books to be translated into English was Herr der Diebe in 2002. It was subsequently released as The Thief Lord by Scholastic and made it to the number 2 spot on The New York Times Best Seller list. The fantasy novel Dragon Rider (2004) stayed on the New York Times Best Seller list for 78 weeks. Following the success of The Thief Lord and Dragon Rider, her next novel was Inkheart (2003), which won the 2004 BookSense Book of the Year Children's Literature award. Inkheart was the first part of a trilogy which was continued with Inkspell (2005), which won Funke her second BookSense Book of the Year Children's Literature award (2006). The trilogy was concluded in Inkdeath (published in Germany in 2007, English version Spring 2008, American version Fall 2008). Funke has been working with Mirada to create a multimedia experience for the iPad based on her Mirrorworld book series.

Week 12, Monday, November 11

Immersion and Extractability

- Henry Jenkins, “He-Man and Masters of Transmedia, “ Confessions of an Aca-Fan, May 21, 2010,

- Henry Jenkins, “Harry Potter: The Exhibition, or What Location Entertainment Adds to a Transmedia Franchise,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, December 14 2009.

- Mark J. P. Wolf, “Immersion, Absorption and Saturation,” Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (New York: Routledge, 2012), pp.48-51.

- Andrea Phillips, “Bringing Your Story Into the Real World,” A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 209-222.

Time to meet with teams

Speaker: David Voss, Vice-President of Design, Mattel Toys

David Voss is Vice-President of Design at Mattel Toys in Los Angeles. He is an alum of the Fashion Institute of Technology.

Week 13, Monday, November 18

Seriality

- Jason Mittell, “All in the Game: The Wire, Serial Storytelling, and Procedural Logic,” in Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (eds.), Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), pp. 429-438.

- Neil Perryman, “Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media: A Case Study in Transmedia Storytelling,” Convergence, February 2008, pp. 21-40.

- Mark J. P. Wolf, “More Than a Story: Narrative Threads and Narrative Fabric,” Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (London: Routledge, 2013) pp. 198-225.

- Sam Ford, “U.S. Soap Operas” (Work in Progress)

- Elena Levine, “’What the Hell Does TIIC Mean?’: Online Content and the Struggle to Save Soaps,” in Sam Ford, Abigail De Kosnik, and C.Lee Harrington (eds.) The Survival of Soap Opera: Transformations for a New Media Era (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2012), pp. 201-218.

- Andrea Phillips, “Conveying Action Across Multiple Media,” A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 93-102.

Prof. Jenkins check-in with teams

Speaker: Katie Elmore Mota, Executive Producer, East Los High

Katie Elmore Mota is CEO of PRAJNA Productions: Stories with Social Relevance, a Los Angeles-based production company that is focused on creating cutting edge television/transmedia programming that is socially relevant for the Americas and beyond. PRAJNA specializes in the development and production of top-rated dramatic series that address a wide array of social and health issues. Prior to founding PRAJNA, Katie served as Vice President of Communications and Programs for Population Media Center, an international NGO

specializing in entertainment-education, for more than 6 years. At Population Media Center, Katie oversaw the design, development, and management of numerous programs using media for social change around the world. Katie was also Executive Producer for a cutting edge new series that takes place in East Los Angeles called, ‘East Los High’ that will go to air in 2013. She also produced a 70-episode novela with MTV for all of Latin America called ‘Ultimo Año,’ which will premier in the US in February 2013.

Week 14, Monday, November 25

Subjectivity And Performance

- Henry Jenkins, “‘We Had So Many Stories to Tell’: The Heroes Comics as Transmedia Storytelling,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, Dec. 3, 2007

- M. J. Clarke, “Tentpole TV: The Comic Book,” Transmedia Television: New Trends in Network Serial Production (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp.27-61.

- Andrea Phillips, “Online, Everything is Characterization,” A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 83-92.

- Sam Ford, “World Wrestling Entertainment: A Case Study,” (Work in Progress).

Time to work with teams

Week 15, Monday, December 2

Final Presentations