The "Creative Child" Meets the "Digital Native": An Interview with Amy Ogata (Part One)

/The Post-War American family turns out to have been a much more complex phenomenon than our stereotypical images of Leave It To Beaver might suggest. The Baby Boom generation, invested in critiquing the values of their parents, left us with an image of the era which is highly conservative, ideologically repressive, emotionally sterile, and materialistic -- there's some truth to these cliches, of course, but there was much more going on. In particular, there was an attempt, coming out of the Second World War, to embrace a conscious project of designing and developing a new generation which would be free of the prejudices of the old, which would be capable of confronting global problems and making intelligent decisions about the Bomb, which would be democratic to its core and thus resistant to future Hitlers, and above all, which would be free of inhibitions which might block their most creative and expressive instincts.

I've long been fascinated by this period but rarely have I seen it written about with the depth and insights that Amy F. Ogata brings to her new book, Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America. Ogata brings a design/art history perspective to bear on the period, telling us more about the ways that ideas about children as expressive beings helped to inform the design of toys, playspaces, schools, libraries, museums, and other public institutions, and beyond that, she offers some glimpses in how these ideas about creativity helped to shape children's books, television, and other popular culture texts. I came to the book for the insights that it might give us into the children's media of the 1950s and 1960s, but I left with a much more immediate sense of how a deeper understanding of how ideas about childhood during that period might speak to our present concerns. As I wrote as a blurb for the book:

At a time when the news media is again concerned about a crisis in American creativity, schools are cutting funding for arts education, major foundations are modeling ways that students and teachers might 'play' with new media, and museums worry about declining youth attendance, Designing the Creative Child makes an important intervention, reminding us that these debates build on a much longer history of efforts to support and enhance the creative development of American youth. I admire this fascinating, multidisciplinary account, which couples close attention to the design of everyday cultural materials with an awareness of the debates in educational theory, public policy, children's literature, and abstract art that informed them.

So, the following interview is designed to explore those points of intersection between the "creative child" as imagined in the post-war period and the "digital native" as conceived in the early 21st century. As a careful historian, Ogata was careful to make some nuanced distinctions between the two, yet she was open to exploring the ways that these older concepts about childhood might still be informing some of our current discussions about digital media and learning.

You open the book with a quote from Arnold Gesell who writes that “by nature” the child was “a creative artist of sorts....We may well be amazed at his resourcefulness, his extraordinary capacity for original activity, inventions and discovery.” This formulation reminds me of contemporary formulations of children as “digital natives” who "naturally" know how to navigate the online world. What do you see as some cornerstones of this belief in the “creative” child? Is the goal for adults to facilitate and support this creativity or to get out of the way and avoid stiffling it?

This is an interesting analogy and one I had not considered. Gesell is articulating a sense of surprise and admiration, and it resembles how we speak about children navigating digital devices. What the concepts of the "creative child" and the "digital native" share is an essentialist belief that children are somehow "naturally" inclined toward certain expressions or activities, and it is very hard to support these kinds of overwhelming generalities. Moreover, while we might praise the "naive" and untutored, behind these sentiments I also detect both a patronizing quality and a sense of loss or regret on the part of the adult. The idea of the creative child is one invented by adults and, as I argue, it serves many different interests, from toy manufacturers to art museums, Cold War ideologues to serious scientists.

The cornerstone of the idea of the creative child is that he or she possesses "natural" insight that comes out in play. Another related belief is that childhood creativity is a fleeting quality that has the potential to provide future gains for the child, her parents, and the nation. Because the idea of nurturing creativity in children was so widespread (and such a big business) after World War II, we tend to understand children's creativity in limited, usually positive terms and we expect it to take certain forms. This, perhaps, is where the creative child and digital native part ways, given the lingering popular suspicion around children and the digital environment (the belief that kids might get themselves or others in trouble). In the historical case I outline, it is a parent's responsibility to facilitate a child's creativity by providing toys, amusements, and spaces for play. But the public was also invested in some of these notions, evident in new public schools, spaces for exploration such as museums, and in art education programs.

What connection existed between the ideal of the creative, expressive child and the growing consumer culture of the post-war period? What kinds of products were able to attach themselves to this particular construction of childhood?

The consumer dimension was a powerful one and has become even more so today. It's hard to escape the rhetoric of creativity if you're shopping for toys or games, or other things like clothing and schools. The child's block, the cardboard box, and crayons were some of the most romanticized and widely prescribed amusements of the postwar age. In addition there were some objects, created by architects and designers, which were deliberately arty and were sold specifically as creativity toys.

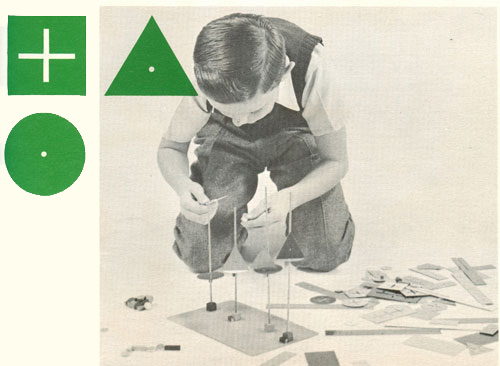

Magnet Master was a magnetic building toy designed by Arthur Carrara and developed as a product of the Walker Art Center. There were no instructions or diagrams because, the museum reasoned, children didn't need them and would do better on their own. The Philadelphia architect Anne Tyng developed a building toy she attempted to market under the idea of stimulating children to build and explore. Charles and Ray Eames's 1950s paper toys were similar but used different materials and were more widely available and for a longer time. But other products, once so ubiquitous, have now completely disappeared. The simple indoor fabric playhouse that draped over a card table is gone, in part because people no longer have those standard-sized card tables.

To what degree was the ideal of the creative child bound up with particular experiences of class, race, and gender? This is, was the expressive child more likely to be middle class, white and male, or did these writers offer a more multicultural understanding of what constituted creativity?

The figure of the creative child in this historical era is extremely middle class, but not exclusively male and not exclusively white. In the early 1950s, white children are implied in the toy ads and housing schemes, by the early 60s, this is still dominant but less so. Creative Playthings placed ads in Ebony, for example, and the Brooklyn Children's Museum's 1970 renovation was very much designed with the local Crown Heights neighborhood in mind. The creative child is a construction that aims to overlook difference while simultaneously selling exclusivity. This is one of the paradoxes of the idea. Creativity is described as something that all children are supposed to possess "naturally," but at the same time parents and teachers are told that it needs careful tending and stimulation, usually through specific kinds of toys and materials.

What role did television play in promoting and supporting this concept of childhood creativity?

Television was of course a central force for the representation of childhood in postwar America and had a role to play in helping to create the specific figure of the creative child. I spend most of my book describing material and spatial forms that do this work, but there are several programs that also had an important role in the making of the idea. Winky Dink, which asked the child to "finish" the story by drawing on a special screen affixed to the TV itself, is an obvious example for harnessing the child's agency, but the character who, I think, best represents the image of the postwar creative child is Gumby.

Gumby's energy and imagination are represented in the many physical forms he takes, and the way he and his sidekick Pokey move in and out of stories, eras, and places. His exuberant inquisitiveness sometimes brings havoc upon himself and his family, but this is of course resolved before the end of the program. The way creativity is constructed on television and in children's books emphasizes the positive and tends toward happy endings.

Often, across the book, it seems that children’s imaginations are linked to various forms of abstraction. What was the relationship between childhood and the modern art world during this period?

You are right about this. Abstraction is one of the recurring motifs of the designed objects and spaces I discuss. Frank Caplan, who was one of the founders of Creative Playthings, believed that undefined shapes and unpainted forms would help to stimulate a child's imagination. The company sought out artists to design toys and playgrounds to enhance their business and for cognitive developmental reasons, but also because they were genuinely interested in the links between modern art and design and objects for children; they collaborated several times with the Museum of Modern Art. This occurred at a time when abstract painting and sculpture was gaining prestige in both the U.S. and Europe, and had a propagandistic role in the Cold War. However, the twinning of abstraction and a child's imagination (evident in forms like children's drawings) is an older idea. Early twentieth-century European modernists deeply admired the representational strategies of children's art. This notion comes back with new vigor in the "Creative Art" education curriculum that asked pupils to express their experiences rather than copy models. There was, then, a demand placed on children to be creative, and often abstract.

Amy F. Ogata is associate professor at the Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture in New York City. She is the author of Art Nouveau and the Social Vision of Living. Her new book, Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America was recently published by the University of Minnesota Press.