In talking about the texts that helped them imagine a queer life by talking through those texts themselves, these queer life writers strike at a core tenet of what makes autobiography a distinct genre of social action—they speak a truth about their lived experience in the voice of others. So, when Jonathan Caouette, in his documentary Tarnation shows us his teenage self lip-synching to the song Frank Mills from the musical Hair, he is not telling us about his reparative reading. He is not narrating the reparative reading as being important to him or to how he came to understand his relationship with his mother, her mental illness, and his own queer identity. He is showing usthe reparative reading itself, in the form of home movie footage of him emoting to Shelley Plimpton’s rendition of the song.

Existing frameworks for understanding what makes autobiography a distinctive struggle to account for this as a meaningful (and indeed complex and moving) instance of life writing, because the youthful Jonathan in the frame is not speaking (he is miming) and the content of his utterance is a popular song performed by a female singer. He violates two basic elements of autobiography as a social and artistic genre here: he does not speak in his own voice, and he does not speak in his own words. Yet the young Jonathon’s commitment to the performance, his use of the song and the video camera to express and give form to his emotions, is undeniably saying something about his lived experience. But what is it saying, and how we can learn to recognize the young person’s statement as being a statement about themselves when it is made in this collaged way?

Caouette the filmmaker does not remediate his youthful reparative reading from the perspective of his adult self reflecting back on his childhood. He puts the lip-synching child in front of his audience and lets him speak for himself. Media materialities play a vital role here, the filmmaker can do this because he is working with digitized footage that allows him to collage many materials together including this material from his personal archive of home movie footage. Caouette bends the material affordances of digital film as far as he can to show us that when the child is trying to understand how to survive he doesn’t speak in his own voice, but in Plimpton’s—how do we listen to that voice coming from, but also clearly not belonging to, that body and hear what he is trying to say?

When it was released into cinemas Tarnationwas infamous for being made entirely in iMovie for a total of around $200 dollars (the soundtrack, on the other hand, was very expensive because of the cost of the rights). In the trailer, a bi-line for the film is: Your greatest creation is the life you lead—and this is a statement of queer flourishing. While largely reviewed as a documentary about Caouette’s relationship with his mother (which it is) the film is, I think, equally a story about how Caouette came to believe in the possibility of his own life, growing up poor and gay in Texas. Tarnation tries to celebrate and see clearly Caouette’s mother’s life, but it also tells the story of the life Caouette made for himself by using dominant culture (movies, television, popular music, musicals) as a resource and engaging in what Sedgwick would call “overreading.”

For a book about the autobiographical impulse in culture, you tell us very little about yourself. If you were to mediate your own life story, given what you learned in researching this book, what form of mediation would you use?

This is a great question! One of the reasons I am scholar of autobiography is that I have immense respect for—bordering on fear of—the nature of the challenge we face when we try to find the right form and media to tell others about our lived experience, who we are, and what matters to us. When I was researching zines as an autobiographical form as part of my doctorate, I become quite frustrated with scholars (and practitioners) who claimed that making a zine was “easy.” While it is true that there are low financial and material barriers to making a zine—a zine can be made out of a single sheet of paper using a pen —having and refining the ideas, working out how to tell the story you want to tell, discovering what your audience does and does not need to know about the context in which you live and the people who are important to you in order to understand what you are trying to tell them is anything but easy. I only came to really appreciate that by choosing the medium of the zine to communicate with zinemakers during my doctoral research—that was an autobiographical project, albeit a meta one: a zine about undertaking a PhD on zines (Poletti).

I think we see the ingenuity it takes to make a seemingly simple piece of life media in the work people put in to learning how to take good selfies (of various genres), to craft Facebook posts that both say what they want to say and compel others to write a comment or click a reaction. Even the most seemingly simple (and some would say banal and ephemeral) forms of self-life-writing actually have quite high and complex aesthetic and formal components that are fundamental to their capacity to create satisfying and meaningful encounters for the authors and their readers.

As I tell my students when I teach life writing and ask them to undertake life writing themselves: the trick with autobiography is that while it is a genre, there is no colour by numbers way to write or produce a piece of autobiographical media. Autobiography always requires ingenuity on behalf of its creator—the material you are seeking to communicate (your identity, your lived experience, your values, your desires and fears) are unique to you, and the text you make to communicate them will have to be unique too.

All that said, I have never really consistently engaged in autobiography until this year when, in early March, I contracted covid-19 (before widespread testing was available in the Netherlands). I was in isolation at home for six weeks with a lung infection and serious fatigue caused by the virus. I was very sick and living alone in a country that did not quite feel like home (I have only lived here for four years). On top of that I become ill right at the beginning of the pandemic, and the medical profession was taking a triage approach to the virus—unless they thought you were in danger of being unable to breathe, they were not able to provide any care. (During this time the proofs came in for Stories of the Selfand I had to do both the index and the proofreading, which was a challenge physically but also a great way to stay anchored to the world while I was alone for so long. That said, I do feel like the index should come with a disclaimer: constructed while the author was suffering from novel coronavirus.)

During this time I was regularly updating my friends and family in Australia about my experience on Facebook, but I was also ‘documenting’ the experience of the virus because I thought people might be interested to know the kinds of impact it could have on a healthy person, and how little the health profession knows about the virus or how to treat it. It was, and still is, a kind of covid-19 chronicle. For many people I am friends with on Facebook, I was the only person they knew who had the virus, and so there was a lot of engagement and support coming through the site because they were curious, horrified, worried. Their responses eased my social isolation, but many of my friends on Facebook also told me that my posts helped them understand the virus and the pandemic better. It was the first time in my life that talking about my lived experience and myself seemed to be useful to my community. Recording the experience on Facebook was mutually beneficial for them and for me. (Although I am sure it may have also increased some peoples’ anxiety about the pandemic, and they may have had to block my posts.)

I am a ‘long haul’ covid-19 case, and I am still recovering, and once I was well enough to work again I wrote a short essay about the physical elements of my experience for the Guardian .This was the first time I had ‘gone public’ with a life writing text. I am still not sure how I feel about it, to be honest, although a number of people from America, Europe, and Australia have written to say they found it comforting to read a personal account that so closely mirrored their own experience with the virus and its ongoing effects during this time when there is little reliable medical knowledge about it. This sense of being useful to people helped me overcome my fear that no-one would care that much about one person’s experience with a ‘mild’ version of the virus—a feeling that plagued me when I was writing the essay.

So, I guess in answer to your question, when I decide to write about my lived experience I choose the media that I think will help me reach the audience I want to speak to.

Works cited:

Berlant, Lauren. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008.

Bodó, Balázs. “Mediated trust: A theoretical framework to address the trustworthiness of technological trust mediators.” New Media & Society. 2020.

Dean, Jodi. Dean, Jodi. Blog Theory: Feedback and Capture in the Circuits of Drive. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010.

Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Hayles, N. K. Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

Jolly, Margaretta. In Love and Struggle: Letters in Contemporary Feminism. Columbia University Press, 2008.

Lejeune, Philippe. On Diary. University of Hawai'i Press, 2009. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/8351.

Marwick, Alice. “Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy.” Public Culture 27. 1. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2798379

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech70 (1984): 151–167.

Poletti, Anna. “Putting Lives on the Record - The Book as Material and Symbol in Life Writing.” Biography, 40.3, 2017. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/359007

Poletti, Anna. Zines. In Ashley Barnwell & Kate Douglas (Eds.), Research methodologies for auto/biography studies. New York: Routledge, 2009: 26-33.

Rak, Julie. Boom! Manufacturing Memoir for the Popular Market. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2013.

Shane, Scott, and S. Venkataraman. “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research.” Academy of Management Review25, no. 1 (2000): 217–226.

Stanley, Liz and Margaretta Jolly. “Epistolarity: life after death of the letter?” a/b: Auto/Biographical Studies 32. 2, 2017: 229-33. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61242/1/2017-5-23_Epistolari.pdf

Tell us about your intriguing concept, “confessional entrepreneurs.” What does it suggest about the mechanisms which not only solicit but profit from our sharing of self in the network era?

I had become very interested in crowdsourced projects that invite the general public to contribute autobiographical fragments because these projects seemed to have such a strong transmedial element—utilizing online publishing (websites), book publishing, live events, podcasts and documentary. On the one hand, these projects seemed to create their own communities of dedicated contributors and followers online, while also appealing to a wider audience: how did they do that? And why was autobiographical content particularly amenable to this form of transmedial cultural production? It was clear to me that projects such as The Moth, PostSecret, Six Word Memoir were of a type—that all did a similar thing (collect autobiographical fragments and compile them into texts available in different media formats). My research began with a pretty basic question: how do these projects work and what makes them successful?

I developed the concept of ‘confessional entrepreneurship’ as a way to categorize the elements that these projects share, at the level of intention (what confessional entrepreneurs are trying to achieve), and how they go about achieving their aims (what specific uses of media, materiality and curation they have in common). I wanted to make a checklist of sorts, that would help identify whether or not a project could be considered as an example of confessional entrepreneurship, with the view that this can be updated as the strategies of these projects change. I also wanted to use the concept to help us think about the unique ways the logic of crowdsourcing is used to source analogue autobiographical texts (handmade postcards, childhood diaries or letters, live events, in person conversation) and that are repackaged into digital products (websites, podcasts, apps) and commercially successful mass market books. Researching these projects made the necessity of studying digital culture from a comparative media studies approach very clear to me—the power of these projects, their ability to claim and market the life narratives they collect as being authentic, is anchored in the materiality of analogue forms of media.

I use the term “entrepreneurship” to conceptualize the projects because even though the vast majority of them fall into a not-for-profit model, they are clearly attempts by individuals, or small groups of individuals who are “concerned with the discovery and exploitation of profitable opportunities” (Shane and Venkataraman, 217). The people behind this projects develop careers in the cultural industries by becoming experts in their particular brand of autobiographical storytelling—that is indeed branded and sold on to corporate and educational clients in some cases (such as The Moth, and StoryCorps). Shane and Venkataraman define entrepreneurship as consisting of two related properties: the presence of potentially lucrative opportunities, and the presence of “enterprising individuals” prepared to take action in response to the opportunities (218). In the case of confessional entrepreneurs, the opportunity occurs in the context of the three interconnected elements of the mid-2000s: the increased influence of memoir and personal storytelling (sometimes referred to as the ‘memoir boom’ which Julie Rak has written about (https://www.wlupress.wlu.ca/Books/B/Boom2), rise of intimacy and affect in the construction of US citizenship outlined by Lauren Berlant in her theory of intimate publics (https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-female-complaint), and the rise of communicative capitalism, theorized by Jodi Dean in her book Blog Theory(https://jdeanicite.typepad.com/files/dean--blog-theory.pdf). At its core—the entrepreneurs have seen that there is an increased expectation that people will engage in personal storytelling, and they have managed to convince millions of people that they need a template or a coach in order to do it well.

Confessional entrepreneurs exploit this cultural context by creating a textual template (secrets on postcards (PostSecret), short spoken work presentations such as those fostered by The Moth, the interview technique of StoryCorps) that they promote and which generates freely generated products that flow into the project via the logic of crowdsourcing. Terms of Service agreements are very important element here but they are not always easily visible: but each of these projects has them somewhere, and they grant the project ownership over the contributions they have crowdsourced and license the entrepreneurs to repackage the content into commercial products. I was interested in both the mechanisms of digital culture and the cultural logics that has led to people having no problem with someone like Frank Warren, or The Moth, claiming ownership of their life narrative. Indeed, the projects create such a convincing framing narrative about the community building and psychological importance of “sharing real life stories” that they convince many of us that contributing to the project is a means of confirms one’s humanity. Sending a card to Frank Warren, or writing a Six Word Memoir, is a way to confirm your membership of the human race (always conceptualized as a narrative race).

In this sense, confessional entrepreneurship works with a participatory logic we see in zines and other subcultures where being a silent audience member is discouraged. However, unlike subcultures where participation is acknowledged as the making of the community, confessional entrepreneurs create projects that they claim meet an existing need for the sharing of personal stories. At the same time, these projects elevate the entrepreneurs (the people with the expertise in autobiographical storytelling) as individuals or small groups who must ‘help’ everyday people tell stories about their lives in engaging ways.

The persona of the entrepreneur is vital to the organisation, coherence and commodification of the autobiographical fragments that are generated by the project—the entrepreneur articulates the logic of the project and names the affects the project seeks to foster (sense of community, relief at sharing a secret, a ‘mortified’ (https://getmortified.com/) relationship with one’s teenage self). The confessional entrepreneur also articulates and polices quite narrow ideas about the form and content of the autobiographical material the project collects in order to establish, stablize and protect the coherence of the commodity the project produces.

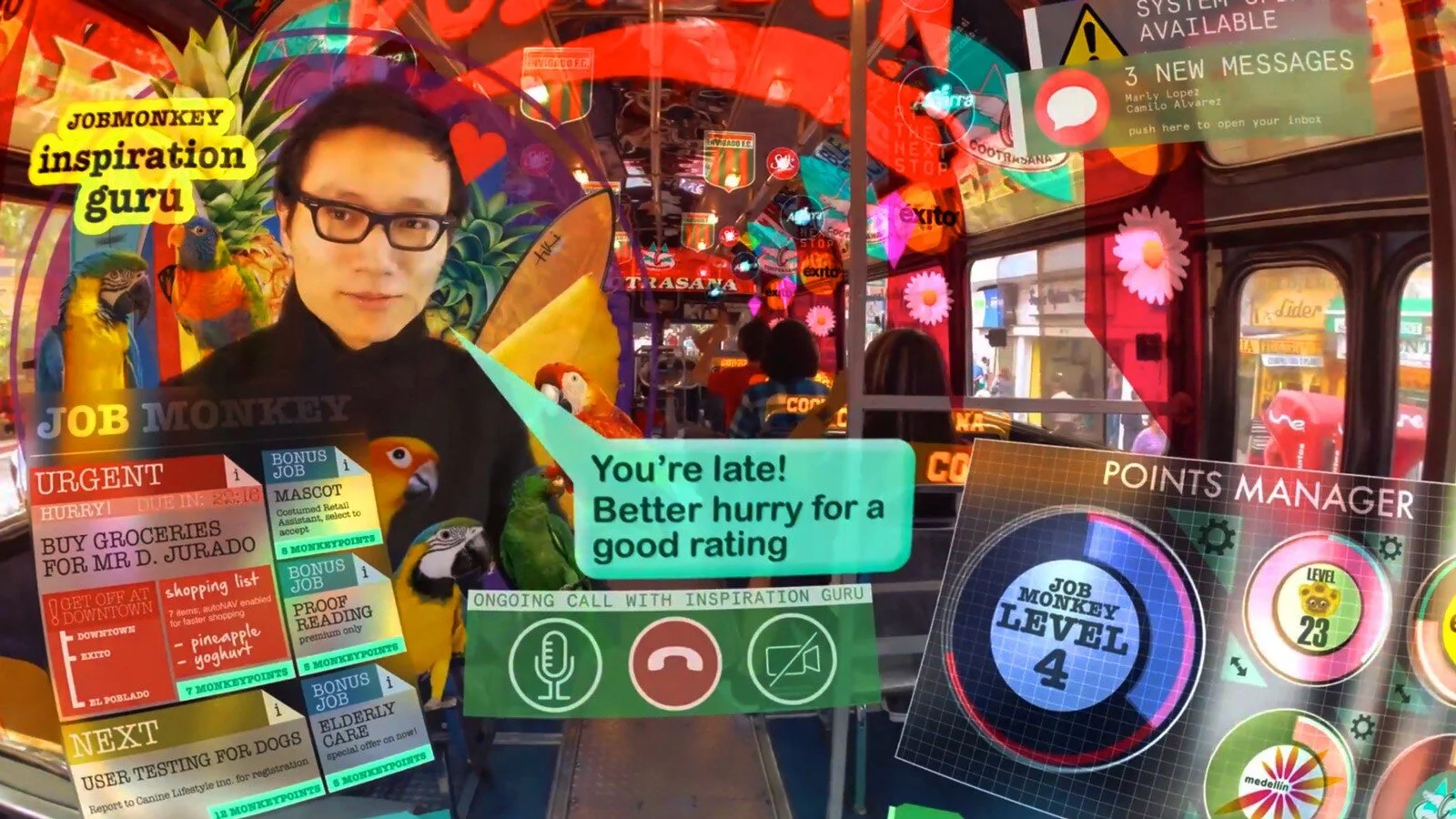

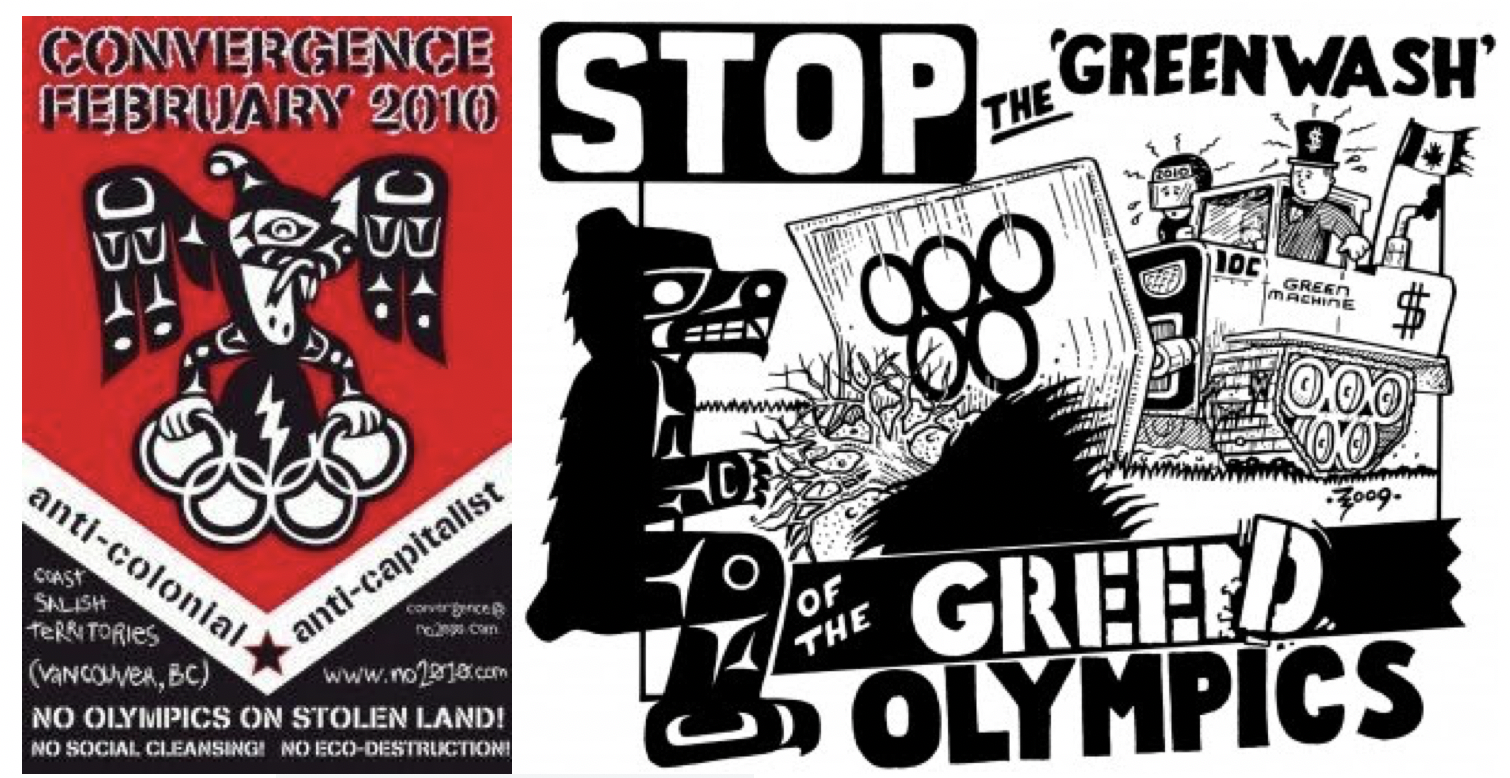

You have very interesting things to say in the book about collage as an aesthetic form for articulating why and how queer lives matter in the context of a normative culture. Yet, collage has become such an everyday practice for many groups in our culture, especially if extended to include such forms of appropriation and quotation as scrapbooks or memes. I would argue that there are a range of different forms of collage practices out there, which express a range of different relations to the dominant culture. If so, what is particularly queer about collage in your eyes?

I agree that collage and appropriation is a wide spread technique that many different groups draw on for different reasons. At the core, what we do when collage is we take ownership of something, we take it apart, and we combine it with other things. We utilize and recombine existing meanings to make new meanings.

Is this an inherently queer gesture? Maybe. If by queer we mean wanting to interrupt and mess around with existing structures of meaning and see what happens. To collage is to say: “well yes but maybe also… this.” It is additive, presumptive, potentially disruptive, and a bit disrespectful.

We often collage with things we love, and when we do that we are loving the text in a specific way—our love for it overruns our respect for its integrity. We love it so much we want to cut it up. This form of loving may not be queer, but it is at least not an entirely respectable way to express one’s appreciation of something. It’s a little bit perverse to want to dismember the thing that brings you pleasure in order to increase your pleasure.

When we collage out of ambivalence, or to demean something, we are also acknowledging the powerful reaction the thing has sparked in us. We may be unconsciously signalling our fetish. We are at least acknowledging the thing has moved us—it has meaning we want to grab on to and work with or on.

I agree that there are a range of difference collaging practices out there, and that they all express different forms of relating to existing meanings in circulation in dominant culture. They may not all be queer, but maybe they enact queer relationships with culture, and produce queer readings of it. I don’t need to claim the aesthetic form itself for queerness, but I do think that it has been used by queer life writers in interesting and important ways, and these have overlooked in autobiography scholarship because of what collage does to authenticity (it destabilizes it).

In Stories of the Self, I am considering how queer life writers use collage to make a text that reflects on the work it takes to construct and believe in the possibility of a queer life. I am taking my lead from the work of Eve Sedgwick, and I approach the survival and flourishing of queer lives as an issue intrinsically linked to inventive, counterintuitive, and disobedient practices of reading and adaptation. In her influential essay “Queer and Now” (https://lgbt200readings.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/week-01_sedgwick_-queer-and-now.pdf)under the heading “Promising, Smuggling, Reading, Overreading,” Sedgwick offers a theory of queer reading in the form of an autobiographical vignette:

I think that for many of us in childhood the ability to attach intently to a few cultural objects, objects of high or popular culture or both, objects whose meaning seemed mysterious, excessive, or oblique in relation to the codes most readily available to us, became a prime resource for survival. We needed for there to be sites where the meanings didn’t line up tidily with each other, and we learned to invest those sites with fascination and love. This can’t help coloring the adult relation to cultural text and objects; in fact, it’s almost hard for me to imagine another way of coming to care enough about literature to give a lifetime to it. The demands on both the text and the reader from so intent an attachment can be multiple, even paradoxical.

In the work of many scholars of queer culture, we see how aesthetic experiences—which are mediated and material—are resources for living. Indeed, the impact of Sedgwick’s influential theory of reparative reading—which offers queer practices of reading and writing as counter-examples to a certain kind of paranoid scholarly reading—enshrines the relationship between life and texts, living and reading, into the heart of a reconsideration of critical practice.

My reading of collage expands this strand of Sedgwick’s work by focusing explicitly on how some queer autobiographers voice their experiences of reparative reading through a very material form of ventriloquism. The queer collages I explore narrate the importance of media texts in the lives of queer young people.

In talking about the texts that helped them imagine a queer life by talking through those texts themselves, these queer life writers strike at a core tenet of what makes autobiography a distinct genre of social action—they speak a truth about their lived experience in the voice of others. So, when Jonathan Caouette, in his documentary Tarnation(https://youtu.be/mLDQL23nutw) shows us his teenage self lip-synching to the song Frank Mills from the musical Hair, he is not telling us about his reparative reading. He is not narrating the reparative reading as being important to him or to how he came to understand his relationship with his mother, her mental illness, and his own queer identity. He is showing usthe reparative reading itself, in the form of home movie footage of him emoting to Shelley Plimpton’s rendition of the song.

Existing frameworks for understanding what makes autobiography a distinctive struggle to account for this as a meaningful (and indeed complex and moving) instance of life writing, because the youthful Jonathan in the frame is not speaking (he is miming) and the content of his utterance is a popular song performed by a female singer. He violates two basic elements of autobiography as a social and artistic genre here: he does not speak in his own voice, and he does not speak in his own words. Yet the young Jonathon’s commitment to the performance, his use of the song and the video camera to express and give form to his emotions, is undeniably saying something about his lived experience. But what is it saying, and how we can learn to recognize the young person’s statement as being a statement about themselves when it is made in this collaged way?

Caouette the filmmaker does not remediate his youthful reparative reading from the perspective of his adult self reflecting back on his childhood. He puts the lip-synching child in front of his audience and lets him speak for himself. Media materialities play a vital role here, the filmmaker can do this because he is working with digitized footage that allows him to collage many materials together including this material from his personal archive of home movie footage. Caouette bends the material affordances of digital film as far as he can to show us that when the child is trying to understand how to survive he doesn’t speak in his own voice, but in Plimpton’s—how do we listen to that voice coming from, but also clearly not belonging to, that body and hear what he is trying to say?

When it was released into cinemas Tarnationwas infamous for being made entirely in iMovie for a total of around $200 dollars (the soundtrack, on the other hand, was very expensive because of the cost of the rights). In the trailer, a bi-line for the film is: Your greatest creation is the life you lead—and this is a statement of queer flourishing. While largely reviewed as a documentary about Caouette’s relationship with his mother (which it is) the film is, I think, equally a story about how Caouette came to believe in the possibility of his own life, growing up poor and gay in Texas. Tarnationtries to celebrate and see clearly Caouette’s mother’s life, but it also tells the story of the life Caouette made for himself by using dominant culture (movies, television, popular music, musicals) as a resource and engaging in what Sedgwick would call “overreading.”

For a book about the autobiographical impulse in culture, you tell us very little about yourself. If you were to mediate your own life story, given what you learned in researching this book, what form of mediation would you use?

This is a great question! One of the reasons I am scholar of autobiography is that I have immense respect for—bordering on fear of—the nature of the challenge we face when we try to find the right form and media to tell others about our lived experience, who we are, and what matters to us. When I was researching zines as an autobiographical form as part of my doctorate, I become quite frustrated with scholars (and practitioners) who claimed that making a zine was “easy.” While it is true that there are low financial and material barriers to making a zine—a zine can be made out of a single sheet of paper using a pen (https://youtu.be/3I7Uk24P-vI) —having and refining the ideas, working out how to tell the story you want to tell, discovering what your audience does and does not need to know about the context in which you live and the people who are important to you in order to understand what you are trying to tell them is anything but easy. I only came to really appreciate that by choosing the medium of the zine to communicate with zinemakers during my doctoral research—that was an autobiographical project, albeit a meta one: a zine about undertaking a PhD on zines (Poletti).

I think we see the ingenuity it takes to make a seemingly simple piece of life media in the work people put in to learning how to take good selfies (of various genres), to craft Facebook posts that both say what they want to say and compel others to write a comment or click a reaction. Even the most seemingly simple (and some would say banal and ephemeral) forms of self-life-writing actually have quite high and complex aesthetic and formal components that are fundamental to their capacity to create satisfying and meaningful encounters for the authors and their readers.

As I tell my students when I teach life writing and ask them to undertake life writing themselves: the trick with autobiography is that while it is a genre, there is no colour by numbers way to write or produce a piece of autobiographical media. Autobiography always requires ingenuity on behalf of its creator—the material you are seeking to communicate (your identity, your lived experience, your values, your desires and fears) are unique to you, and the text you make to communicate them will have to be unique too.

All that said, I have never really consistently engaged in autobiography until this year when, in early March, I contracted covid-19 (before widespread testing was available in the Netherlands). I was in isolation at home for six weeks with a lung infection and serious fatigue caused by the virus. I was very sick and living alone in a country that did not quite feel like home (I have only lived here for four years). On top of that I become ill right at the beginning of the pandemic, and the medical profession was taking a triage approach to the virus—unless they thought you were in danger of being unable to breathe, they were not able to provide any care. (During this time the proofs came in for Stories of the Selfand I had to do both the index and the proofreading, which was a challenge physically but also a great way to stay anchored to the world while I was alone for so long. That said, I do feel like the index should come with a disclaimer: constructed while the author was suffering from novel coronavirus.)

During this time I was regularly updating my friends and family in Australia about my experience on Facebook, but I was also ‘documenting’ the experience of the virus because I thought people might be interested to know the kinds of impact it could have on a healthy person, and how little the health profession knows about the virus or how to treat it. It was, and still is, a kind of covid-19 chronicle. For many people I am friends with on Facebook, I was the only person they knew who had the virus, and so there was a lot of engagement and support coming through the site because they were curious, horrified, worried. Their responses eased my social isolation, but many of my friends on Facebook also told me that my posts helped them understand the virus and the pandemic better. It was the first time in my life that talking about my lived experience and myself seemed to be useful to my community. Recording the experience on Facebook was mutually beneficial for them and for me. (Although I am sure it may have also increased some peoples’ anxiety about the pandemic, and they may have had to block my posts.)

I am a ‘long haul’ covid-19 case, and I am still recovering, and once I was well enough to work again I wrote a short essay about the physical elements of my experience for the Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jul/20/i-was-regarded-as-having-a-mild-case-of-covid-19-i-had-burning-lungs-and-exhaustion-for-weeks).This was the first time I had ‘gone public’ with a life writing text. I am still not sure how I feel about it, to be honest, although a number of people from America, Europe, and Australia have written to say they found it comforting to read a personal account that so closely mirrored their own experience with the virus and its ongoing effects during this time when there is little reliable medical knowledge about it. This sense of being useful to people helped me overcome my fear that no-one would care that much about one person’s experience with a ‘mild’ version of the virus—a feeling that plagued me when I was writing the essay.

So, I guess in answer to your question, when I decide to write about my lived experience I choose the media that I think will help me reach the audience I want to speak to.

Works cited:

Berlant, Lauren. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008.

Bodó, Balázs. “Mediated trust: A theoretical framework to address the trustworthiness of technological trust mediators.” New Media & Society. 2020.

Dean, Jodi. Dean, Jodi. Blog Theory: Feedback and Capture in the Circuits of Drive. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010.

Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Hayles, N. K. Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

Jolly, Margaretta. In Love and Struggle: Letters in Contemporary Feminism. Columbia University Press, 2008.

Lejeune, Philippe. On Diary. University of Hawai'i Press, 2009. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/8351.

Marwick, Alice. “Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy.” Public Culture 27. 1. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2798379

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech70 (1984): 151–167.

Poletti, Anna. “Putting Lives on the Record - The Book as Material and Symbol in Life Writing.” Biography, 40.3, 2017. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/359007

Poletti, Anna. Zines. In Ashley Barnwell & Kate Douglas (Eds.), Research methodologies for auto/biography studies. New York: Routledge, 2009: 26-33.

Rak, Julie. Boom! Manufacturing Memoir for the Popular Market. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2013.

Shane, Scott, and S. Venkataraman. “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research.” Academy of Management Review25, no. 1 (2000): 217–226.

Stanley, Liz and Margaretta Jolly. “Epistolarity: life after death of the letter?” a/b: Auto/Biographical Studies 32. 2, 2017: 229-33. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61242/1/2017-5-23_Epistolari.pdf

Anna Poletti is Associate Professor of English Literature and Culture at Utrecht University (the Netherlands). They are a researcher of contemporary life writing, and a co-editor of the journal Biography: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly. They are the author of Life Narratives and Youth Culture: Representation, Agency and Participation (with Kate Douglas, 2016), and Intimate Ephemera: Reading Young Lives in Australian Zine Culture (2008). With Julie Rak, they co-edited Identity Technologies: Constructing the Self Online (2014).