Trust and American Democracy

/This is the first of a series of blog posts written by the PhD students in my seminar, Public Intellectuals: Theory and Practice. Over the next few weeks, I, like a proud father, will display my student’s work.

Trust and American Democracy

by Jackson De Vight

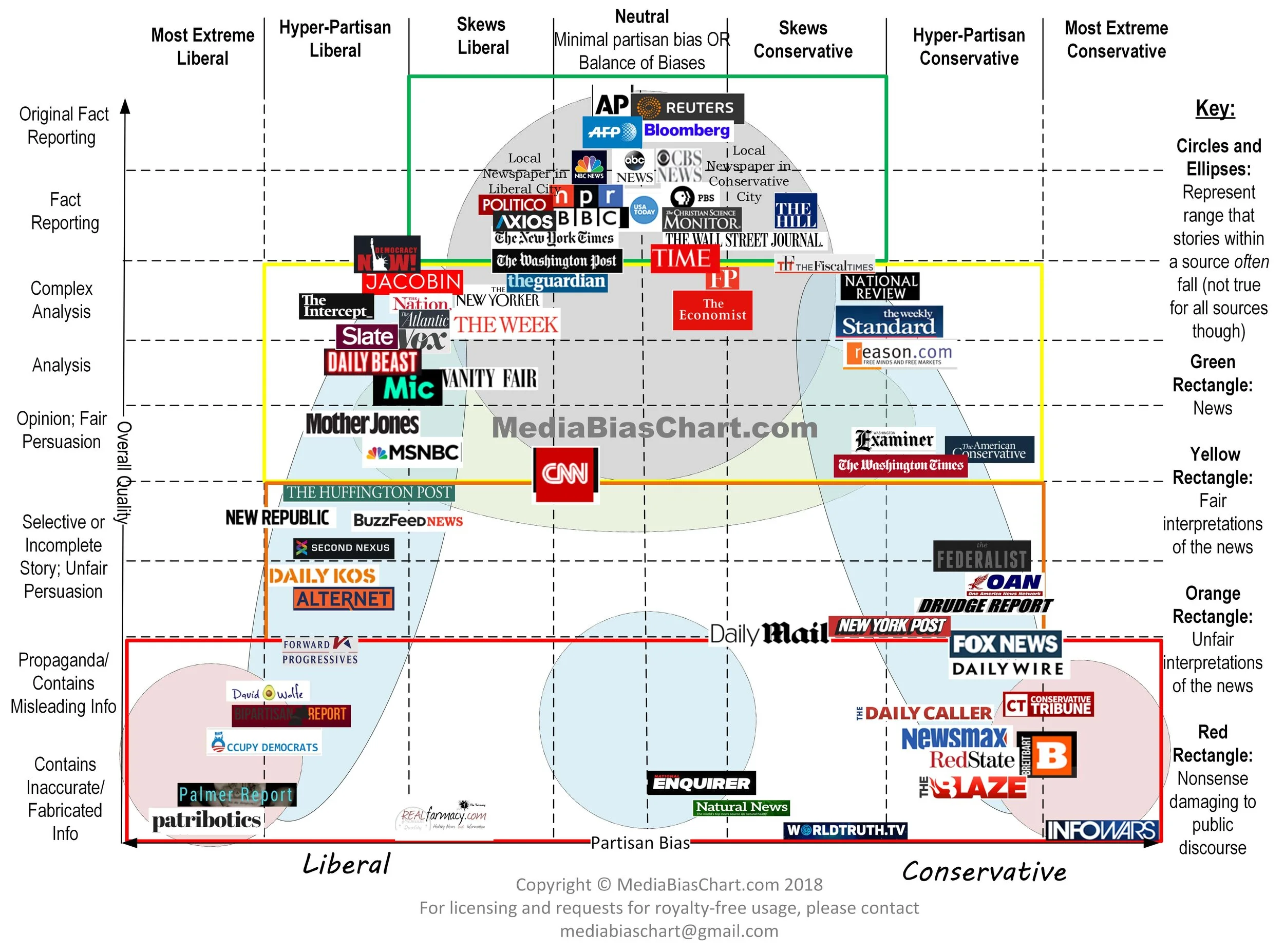

Over the last three decades partisan polarization has steadily increased across every societal arena, including perception of news organizations, trust in political opponents’ good faith, and opinions of institutions like churches or media outletsassociated with the other side. As a society we used to have a certain level of trust in major institutions even if we knew they were somewhat flawed, and that common ground and experience provided a space for us understand and discuss issues. Today, such an ideal seems almost unreachable. Americans are increasingly suspicious of traditional news sources, such as network and cable news, national newspapers, or public radio, fearing that they are biased or ‘fake news.’ At the same time, on both the left and right, partisan sources – from Fox News to MSNBC – have further polarizedhow many Americans get their news. In a way, these partisan news sources are making those fears come true by the very act of giving consumers an ‘unbiased’ [read: they agree with me] news source.

We don’t have a set of common sources we can agree on for the facts, and that’s a problem because before we can have a worthwhile discussion about what should be done, it’s important that we have agreement on what’s happening in the first place. This trend has been on the uptick for some time, but at some point I think that gradual increases build up to a complete change, which is exactly what I think has happened with the current outrage over the impartiality of institutions like the post office and ballot counting. This ought to be of utmost importance across the political spectrum, and cannot be another space in which those vaguely sympathetic to Donald Trump’s policy positions or judicial appointments wave off criticism of his combativeness as an unfortunate but understandable element of his character. This attack is not limited to cultural institutions like the New York Times or NPR, but an assault on one of the core presumptions of the American system. This category difference matters. I’ll make my case here as if I were narrating how I think through these sorts of questions that contain both nerdy theoretical ideas and some more grounded and specific analysis.

To start I’ll try to justify why I think this issue matters, followed by some work to define some terms – how do I define undermining and how I define whether or not it’s occurring, and finish with some responses to the sorts of pushback I expect a reasonable, good faith opponent might levy against me. I need to be clear – I disagree profoundly with the sitting president and those who still support him, but that’s not what I want to talk about here. My study of the fractured news climate in our country and how it shapes people’s perception of reality has pushed me to genuine care and humility in how I approach these issues. The contemporary media landscape deals heavily in whole narratives rather than providing strictly factual accounts, and it is my hope in this blog piece to temporarily peel back the some assumptions surrounding this situation just long enough to plant seeds of thought on this critical issue.

Before I step into the nitty-gritty of how I think through electoral misconduct, I want to lay out my reasoning for why this question has even arisen during this most unusual of elections. There are two major reasons why the validity of this coming election have been cast into doubt. First, as noted previously, the sitting president and some of his supporters appear to be trying to castinto question the conditions under which they would ensure a peaceful transition of power. They have cited concerns about election fraud, and at times implied that a loss would mean that fraud had taken place!

The persuasiveness of this approach is somewhat compounded by the second contributing factor: mail-in ballots. An unprecedented percentage of voters are expected to vote by mail this year due to changes caused by COVID-. This presents a number of potential strategic concerns for the GOP. Democratsare more likely to vote by mail than Republicans both nationwide and state-by-state. Older voters, a demographic which had until March firmly favored Trump in most relevant states, decidedly flipped due to his handling of the pandemic.

Furthermore, the speed at which vote by mail has been expanded across the country has substantial consequences. Most polling and vote counting is done by dutiful but busy and often older volunteers, meaning that rapid changes in how voting is carried out can cause significant misunderstandings, delays, or errors. In states which have gone from either no or very limited general mail in ballots there may simply not be sufficient resources to process the vote counts as quickly as they did with the previous system. Most states prohibit pre-Election Day ballot counting to prevent leaks or influencing in-person voters, and the logistical challenge of both manning polls and counting mail-in ballots is likely to either make the former severely understaffed, or to make ballot counting from the latter stretch over the coming week. In the past, the overall result of races have rarely been changed by mail-in ballots. The percentage of votes cast in person and the skew one way or the other in mail-in ballots was insufficient to make a difference. In this case, however, it’s entirely possible that a number of important state and national elections, including the presidential race, could break that mold entirely due to these rapid reforms.

Like any good academic I have a strong, some might say annoying, tendency to fixate on definitions and categories. How and where we sort various ideas, issues, and people in our mental bookshelves is often an unconscious but nevertheless vital aspect of critical thought and belief. For instance, whether or not you consider gravity a law (so nearly always true it’s best just to live like it’s an iron-clad rule) or a theory (an interesting but unproven explanation or pattern) will have major implications for your life! In my mind there are two general ways of approaching the question of electoral legitimacy. First, one could say that in order to believe the results of the election they themselves, or one of their hand-picked representatives or trusted sources must personally observe enough of the election results to guarantee their legitimacy. Forgive what might sound like a sarcastic tone, I don’t mean it that way at all– this is an extreme but rational extension of a natural tendency to draw tight boundaries around ‘your people,’ particularly when wider, less personally connected sources are cast into doubt! There’s an important distinction to be drawn here, however.

Sometimes we can be drawn into what social scientists call a ‘parasocial relationship’ with news organizations or pundits. These parasocial connections are essentially where aspects of a real, two-way relationship such as you might have with a friend or family member is transferred to a media figure. This tendency is very common! Teens develop emotional attachments not just to the music from their favorite artists but the artists themselves, any number of sports fans treat longtime coaches of home teams like heroes or traitors, and real, genuine senses of personal loss may accompany the death of a longtime favorite actor or activist. I don’t make this point to dismiss the validity of any of these feelings, but rather to note that the ‘one of us’ set of emotions which can so easily transfer to news figures who we agree with and enjoy the style of can cause real trouble. Unlike actors, athletes, or musicians who may depart their area of expertise and discuss politics and society, news outlets are conduits for facts themselves and granting an organization the benefit of the doubt out of loyalty to a shared ideological position may, over time, seriously skew your perception of reality. After all, a domestic news organization covering an American presidential election has much more bias in reporting than the same organization might have covering an election in Eastern Europe, Africa, South America, or Asia, where outside observation may indeed be the most trustworthy metric for electoral legitimacy in part because there’s less motivated reasoning at play.

In short, I encourage you to think critically about who you sort into the absolutely trusted, generally trusted, trusted if corroborated, doubted, and patently untrustworthy buckets. If you’re anyone like me, almost every major news source should be right in the middle of that spectrum. Try to develop a robust background of each source’s history, the coverage from other sources, and a good nose for nonsense to test each story, especially the ones you want to believe.

The second approach to validating the legitimacy to the election is to trust the institutional mechanisms formally set out as the legal authorities for ensuring electoral legitimacy. There is crossover with the previous approach, of course. Instead of putting trust in news figures, individual politicians, or internet media groups trust is put in a formal system. I don’t want to seem dismissive that both notions involve trust, they most certainly do, nor imply that I think the electoral system is some unchanging bedrock in civic society. Quite the contrary! The system of elections has changed frequently across the United States, including reforms to how ballots are written and counted, how folks in various places and demographics are allowed to vote, and the weight of votes relative to votes in other precincts and states. Another important point is to remember that the federal government does not operate even federal elections! That work is entirely conducted from the state on downward, with federal regulation and engagement limited to issues of campaign finance and, in rare cases, judicial involvement in contested races. Mail-in ballots, precinct staffing, and all the other attending details are much more localized. This has, aside from atypical situations like the Hanging Chads in Florida during the 2000 election, rarely prompted much national-level outcry, much less serious accusations of electoral misconduct.

With these two broad approaches of assessing electoral legitimacy in mind, I want to lay out how I think through the all-important question of whether or not an election is illegitimate. To my mind there are three components to whether an election’s resultis illegitimate. First, there must be sufficient evidence of misconduct to question the validity of some set of votes. This could include illegal acts like stealing or counterfeiting ballots, which take place prior to a ballot being entered, or as part of the counting of ballots through negligent or intentional exclusion of some particular set of ballots, but it must be provable to a wider public, not mere conspiracy.

Second, the counts cast into doubt must be of sufficient magnitude to be consequential to the election’s results. While popular vote totals may be helpful perceptually, our system does not operate as a count of totality. For example, even if the long-publicized issue of ballots being sent in by deceased voters in Chicago (a totalof 229 votes from 119 ‘voters’ according to bipartisan commission) were a thousand times more severe it would not have changed which presidential candidate Illinois voted for in over thirty years.

Finally, the counts in question must be cast in a state where the suspected misconduct would change the allocation of electors in sufficient quantities to change the election’s outcome. Now, before I am carted off to be burned for what may seem to be outrageously generous standards, let me be clear: these are not thresholds for whether election tampering has taken place, but rather thresholds for whether that tampering has made an entire race’s results untrustworthy. Concerns surrounding the detection and prosecution of ballot misconduct is entirely valid and should be pursued to the utmost extent of the law, which I must note is remarkably strict.

The question here, the critical issue which threatens to undermine the core principals and practices of this nation, is whether the end result of the presidential election in 2020 can be trusted, and under what conditions those results are to be determined. So far I have tried my best to describe why I think this issue is pressing for our contemporary moment, provide general categories for how folks tend to put their trust in the results of elections, and to make as clear as possible my bright-lines for what would and would not cast the results into doubt. From here, all that remains is to discuss the probability of electoral illegitimacy and to briefly game out the most likely scenarios for the week of November 3rd.

I must begin my discussion of election-changing mishaps or misconduct with a warning. I do not trade in conspiracy theories, and as flawed or imbalanced as the various institutions, scholars, news organizations, partisan and bipartisan political commissions, authors, law enforcement agencies, and other such mainstream bodies may be, the notion that they, with all the checks and balances they are subject to, all cooperatively or coincidentally stand together against truth is preposterous. One ought to corroborate information from any of those sources, but anonymous leaks, internet diatribes, and discredited figureheads do not bear on this analysis. Fortunately, unless you are given to the notion that both political parties and every layer of the news, legal, and credible watchdog worlds are in on a plot to radically downplay massive voter fraud and ballot counting errors, we can trust that the study and investigations into these issues offer at least ballpark figures for what we can expect.

The first set of ballot question marks likely to arise in November centers on criminal or negligent tampering with ballot distribution, alteration, or collection. FBI Director Christopher Wray noted in a congressional hearing on September 24ththat the FBI has been monitoring but has seen no evidence of coordinated voter fraud, either historically or in this election cycle, though both White House press secretary McEnany and Attorney General Barr argued that this analysis is irrelevant in such an unprecedented mail-in election. Further, the sum total of voter fraud cases documented by any credible news organization, including conservative sources, during the 2016 election was four, including Terri Lynn Rote, an Iowa woman who voted twice for Trump, Phillip Cook, a Texas man who voted twice for Trump and then claimed he was working for the Trump campaign when he was caught, Audrey Cook, a Republican election judge in Illinois who voted on behalf of her dead husband, and Gladys Coego, an election volunteer in Florida who filled in a mayoral bubble on a ballot she was counting. Rote, Mr. Cook, and Coego were arrested and charged, while Ms. Cook’s ballot was discarded.

The sum total of suspected but documented cases for the 2016 election totals, at most number under a hundred out of over a hundred and thirty million ballots cast. Even if that number were a hundred times a hundred it wouldn’t have changed the results even in America’s least populated district, Rhode Island’s 1stwhich has around 500,000 residents and 200,000 active voters. This data certainly isn’t conclusive given the nature of a blog post, but I hope it’s illustrative for how unlikely election-changing fraud is in our system.

The second, and far more likely, ballot issue for 2020 has to do with notcounting genuine votes rather than counting fraudulent ones, and not along any lines of political bias whatsoever. Each state has some combination of four or five methods for ensuring the legitimacy of ballots, and each year genuine ballots are thrown out due to issues like incorrectly mailed forms, subjective judgements about matching signatures, and machine errors. This is significantly more of an issue with mail-in ballots, especially in states new to the practice, which due to the demographics who tend to vote remotely will hurt Biden more than Trump.

There are a number of feasible scenarios for how November 3rdand the ensuing week plays out.

- If we take present polling at face value and maintain the assumption regarding who will benefit more from mail-in voting, Biden will win the race on Election Day and his lead will continue to grow as more mail-in ballots are counted.

- The second most likely scenario is essentially a tie or narrow lead by Trump on Election day, perhaps again losing the popular vote, but Biden doesn’t concede given the unprecedented number of ballots which won’t have been counted yet. If those mail-in ballots flip some important states and Biden ends up winning the electoral vote, especially if it’s close or he loses the popular vote, the groundwork laid by the president and his campaign for claiming a stolen election will kick into gear. Based on the data we have, which is admittedly premised on extrapolations from prior to the COVID-19 complications, it is extremely unlikely that the president will fair better than his challenger in mail-in ballots.

- The least likely, but certainly possible way this election plays out, is that Trump wins sufficiently on election night for Biden to concede and no transition of power takes place, shifting attention to the various congressional and state-level elections.

What exactly a crisis such as that mentioned in the second scenario would entail is beyond the scope of this piece or any precedent in American history, but do note two key facts. First, partisanship has become more rabid and violent over the last few decades – over a third of voters from both parties polled by YouGov and the Voter Study Group expressed openness to violence for advancing political goals, up from 8% in November of 2017. Second, the record of presidents peacefully and graciously leaving office and the public by and large avoiding violent protest could, potentially, be threatened if this election’s results are too contentious., The assumption of reasonable observers has been that that if Trump were in fact as insane and power hungry as his more extreme critics claim and refused to leave his office he’d be kicked out of the White House as a tresspasser, no longer president no matter what he claimedWhile the contingency of the election being in such doubt as to carry into 2021 is unlikely in the extreme, the very idea of a contested election could foment unrest leading to tragedy.

If you find yourself to be open to the idea that an election might be fraudulently decided this November, I encourage you to think through precisely what conditions would lead you to make that determination. Then, as much as you can, stick to them. I understand that if you’ve spent the last three years miserable with Trump as president, it could be remarkably attractive to undermine the legitimacy of the election if he were to win. The same is perhaps even more true if you are a Trump supporter and feel as though he’s the first chance you’ve had to fight back against institutions which are contrary to your beliefs and best interests. This country needs to be bigger than one election, and it is up to each and every one of us to put aside our biases to recognize that faith in our system must far transcend faith in one man, party, policy, or cultural belief.

Jackson De Vight is a doctoral student in Communication Studies in the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California where he researches political rhetoric, voter behavior, and security narratives in the media. His past work includes discussions of TSA checkpoints, the cultural location of the national anthem as seen through the Colin Kaepernick protests, and a rich history in speech and debate. As of 2020 he remains committed to a robust interdisciplinary approach, spending most of his free reading on topics ranging from cookery to economics and his free time fishing, working in the woodshop, and carrying on intellectually stimulating and utterly unimportant arguments with his friends.