Jamming the Olympic Rings: Anti-Olympics Art Across Space and Time

/This is another in a series of blog posts written by the PhD students in my Public Intellectuals Seminar.

Jamming the Olympic Rings: Anti-Olympics Art Across Space and Time

by Cerianne Robertson

I can still recite so many of their names. The names of the gymnasts from Romania, Russia, China, and the United States who tumbled their way into my heart in 2000, the year of the Sydney Olympics. I was nine years old. The perfect age to be enchanted by a sport. The way I saw it, those young women defied gravity and embodied power, all under the majestic icon of the interlocked Olympic rings. I was hooked. At my own gymnastics practice that week I imagined dismounting my bar routine onto a mat emblazoned with the five rings, saluting the adoring crowd. Those rings meant dreams. Those rings meant excellence.

This is just what the International Olympic Committee (IOC) wants, of course. In 2019 the organization published an article claiming that people around the world associate the five rings with concepts like "global," "diversity," "heritage and tradition," "inspirational," "optimistic," "inclusive," "excellence," and "friendship.” The IOC touted its logo as “one of the world’s most widely recognized symbols.”

Nine-year-old me was a sucker for that branding.

Twenty years later, the rings mean something very different for me. I first encountered anti-Olympics graphics while reporting in Rio de Janeiro for RioOnWatch, a platform that monitored urban transformations as the Brazilian city prepared to host the 2016 Olympics. As the city evicted an estimated 77,000 people and as police violence against the low-income, predominantly Black residents of favelas spiked, I encountered comics like the one drawn by Brazilian artist Carlos Latuff below. The red Olympic ring turns into blood gushing from a man’s body as a police helicopter flies overhead, a reminder that police killings in the state of Rio de Janeiro doubled in the three months before the 2016 Olympics compared to the same period in the previous year.

“The gold, silver, and bronze are over but the lead continues!” Image by Carlos Latuff (Rio 2016).

From mass demonstrations across Brazil to grassroots campaigns in Boston, an increasingly critical global public discourse has linked sports mega-events to public debt, evictions, real estate speculation and gentrification, spikes in police brutality and surveillance, environmental destruction, and corruption. Over the course of the past decade an unprecedented number of cities have dropped their bids to host the Olympics Games.

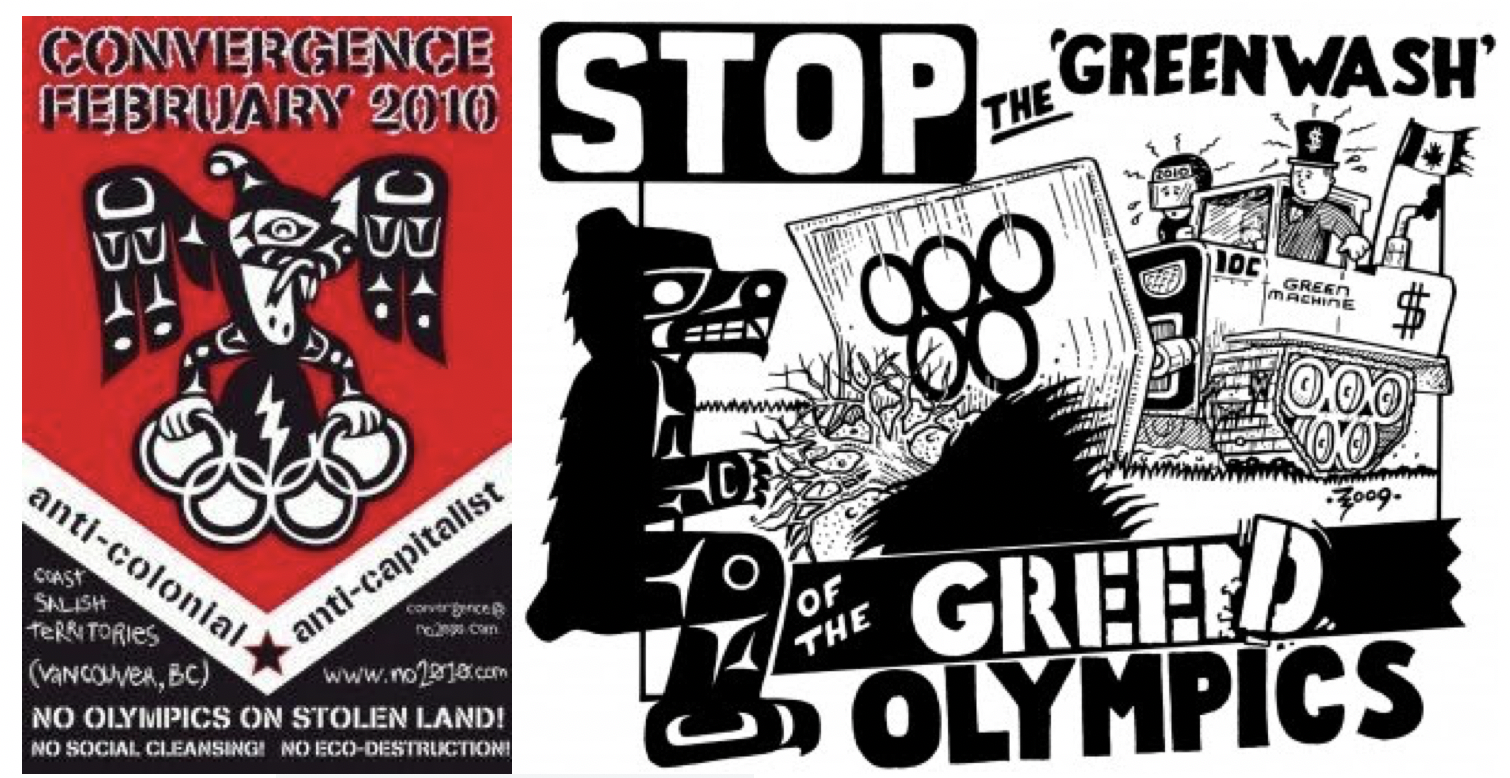

As part of my PhD research on contested narratives about Olympics host cities, I’ve been collecting, archiving, and analyzing art and graphics produced by anti-Olympics activists or Olympics watchdog groups. I’ve compiled many of these images in an informal archive on Flickr. (And I’ve stored many more on my computer as I find excuse after excuse to procrastinate on uploading them.) It turns out Carlos Latuff is only one of many artists — spanning across continents and over the course of decades — who have transformed the Olympics rings in order to critique the Games. Images from Vancouver, for instance, paired the Olympic rings with Indigenous iconography, accompanied by text reminding viewers that the 2010 Games were taking place on unceded Indigenous land. Another poster embedded the five rings into the tires of a tractor clearing a tree, a reference to deforestation to make way for ski runs in Vancouver.

Left: Image from antiolympicartscouncil.tumblr.com/ (Vancouver 2010). Right: Image by Zig Zag (Vancouver 2010).

The employment of the rings in these images suggests that the IOC is right that the Olympic rings are globally recognizable, but that the question of what values are associated with that symbol is highly contested.

As I started to see more and more hijackings of the Olympics rings by anti-Olympics activists, I started to wonder what patterns we might find in the way the rings are appropriated. I also wondered what role these visual subversions could play in challenging the powerful global network of elites that make up or support the IOC.

Policing and the rings

Policing, surveillance, and incarceration collectively constitute the most common theme captured in the visual subversions of the Olympic rings that I’ve collected thus far. In several of the images I’ve encountered, the rings are reimagined as handcuffs, like in these examples from Vancouver 2010 and Beijing 2008.

Left: Image from no2010.com (Vancouver 2010). Right: Image from the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (Beijing 2008).

The rings have also often been redrawn as barbed wire fencing, as in these examples from LA 1984 and Rio 2016.

Left: Image from the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (LA 1984). Right: Image from the Rio de Janeiro Popular Committee of the World Cup and Olympics (Rio 2016).

This art also reflects a concern with surveillance, with the rings turned into lenses through which state (or corporate) power might watch and monitor.

Left: Image by Zig Zag (Vancouver 2010). Right: Image from Random Blowe blog’s Anti Olympic Poster Competition (London 2012).

These themes may seem surprising to some Olympics fans, but probably won’t surprise anyone who has actually lived near Olympics infrastructure, where security is usually designed to be spectacularly visible. These themes will be even less surprising to folks from racialized and/or marginalized communities who are often targeted in police ‘crackdowns’ ahead of the Games to make the area more ‘secure’ for visitors (and more desirable for global corporate sponsors). Ahead of the Olympics, host cities typically expand their police forces (both in terms of personnel and weapons) and call on armed forces, multinational private security firms, and global intelligence networks to support operations during the Games. Meanwhile protests and activism that might be tolerated under normal circumstances are restricted and criminalized throughout the ‘state of exception’ of the Olympic Games.

It is no wonder then that counter-Olympics artists opt to subvert the positive values the IOC wants to associate with the rings and associate them instead with more nefarious imagery, including symbols of oppression and state violence.

Challenging sacred and supreme authority

If you check out how the IOC talks about the rings, it’s easy to see why they make such a juicy target for activists and critics. It’s not just their malleable shape that lends itself to transformation. It’s also about the symbolic weight the IOC itself has bestowed on these five linked circles.

One page of the IOC’s website is dedicated entirely to the rings, describing them as “the visual ambassador of Olympism for billions of people.” That’s quite a weighty role. Another IOC webpage explains:

The Olympic Movement is the concerted, organised, universal and permanent action, carried out under the supreme authority of the IOC, of all individuals and entities who are inspired by the values of Olympism…. Its symbol is five interlaced rings. The goal of the Olympic Movement is to contribute to building a peaceful and better world by educating youth through sport …

Here, the IOC declares itself the “supreme authority” over its “movement.” Someone unfamiliar with the IOC might imagine that this is a bizarre but ultimately harmless exaggeration. But the IOC’s claim to “supreme authority” reflects the iron-fisted control with which it has protected its trademarks (including the rings), enforced its corporate sponsors’ exclusive marketing rights, and even insisted that host countries adjust their laws in order to restrict protests related to the sports event.

The combination of the IOC’s insistence on authority and its simple narrative of building a peaceful world call for a consideration of Nick Mirzoeff’s concept of visuality. Visuality is “that narrative that concentrates on the formation of a coherent and intelligible picture of modernity that allowed for centralized and/or autocratic leadership,” Mirzoeff writes in The Right to Look(p. 23). He adds that visuality is “that authority to tell us to move on” (p. 2), the way a police officer might tell us “there’s nothing to see here” (p. 1). The Olympic media event is a struggle over where to look: the producers and corporate sponsors of the event insist that everyone should watch the official content they generate.

Anti-Olympic art refuses those instructions. It subverts the rings and associates them with evictions, policing, marginalization, and corporate greed, among other manifestations of power and inequality, insisting on what Mirzoeff calls the “right to look.” Rather than focusing on the subjects included in the TV version of the Olympics — often wealthier, whiter people who can afford tickets — anti-Olympic art puts on a spotlight on those who are excluded from the sports event and caught up in larger processes of exclusion related to the Olympics, including Black, brown, and unhoused targets of police sweeps in LA, Indigenous communities in Vancouver, and favela residents in Rio, among others.

By linking the rings and the Olympics to other institutions like real estate developers, police, corporations, and autocratic governments that are more visibly political than the IOC, anti-Olympic art disputes the IOC’s claims that it just “place[s] sport at the service of humanity” from a position of political neutrality. It not only critiques the “supreme authority” (the IOC), but by appropriating the IOC’s primary symbol it enacts a challenge to that authority, producing a reality in which the IOC does not reign “supreme” over its claimed property.

Anti-Olympic art makes visible the struggle and contradiction that exists around the Olympics. Each visual subversion of the rings chips away at their supposed sanctity.

The power of ‘no’

All of these examples can be considered culture jamming, which Mark Dery defines as to “appropriate, rework, and disseminate cultural symbols in order to contest meaning and challenge dominant forms of power.” Culture jamming often targets corporations and consumer culture. Some recent writings on culture jamming have criticized this form (see below) of hijacking corporate or institutional imagery, arguing that it offers a negative critique but doesn’t offer solutions, alternatives, or ways for people to engage.

Artist: Klaus Staek. Image from the Center for the Study of Political Graphics.

What’s interesting from the images I’ve been able to collect is that, yes, they’re incredibly negative. They are part of campaigns that say “no” to the Olympics. Literally. The rings are appropriated into the letter “o” of “no” or “fuck off” (“foda-se,” in Portuguese), or transformed into prohibition signs.

Embracing negation extends beyond the rings imagery, too. The recent campaign against the 2024 Olympics bid in Hamburg, Germany is a particularly great example. The official logo for the Olympic bid was this “Fire and Flame” symbol below:

Image from Hamburg 2024 committee (Hamburg 2024 bid).

And since the official image of the pro-Olympics campaign was fire, guess what the anti-Olympics group adopted as their logo?

Image from NOlympia Hamburg (Hamburg 2024 bid).

A fire extinguisher. (And occasionally a watering can.) They fully embraced the idea of being the “anti” campaign. And this campaign was successful! Hamburg withdrew its Olympic bid after 52% percent of residents voted against hosting in a referendum in 2015, proving that a campaign based on saying no to something can be a winning strategy with concrete results in a struggle against a coalition of powerful global elites. Part of why saying ‘no’ to the Olympics can be generative — even if it doesn’t appear proactive or offer clear proposals — is that it is often asserted in the context of a ‘right to the city’ framework. Anti-Olympic campaigns have insisted that cities’ residents should have power over the decisions that affect their lives and urban environment. They’ve argued that preparing to host an Olympics opens the way for multinational actors to exploit the city for profit and for local elites to build a more exclusive space — the opposite of ‘right to the city’ demands.

In cases where cities have actually held referenda to vote on hosting the Olympics, this argument has been pretty successful. Since 2013, at least five cities have held referenda in which a majority voted against the bid (versus one referendum in which residents of Oslo initially voted in favor of hosting, before the city ultimately dropped its bid anyway after public opinion soured on the idea). Another six cities have dropped their bids due to a lack of support.

In voting against an Olympic bid, a city’s residents are saying “no” to a club of powerful actors including multinational corporations, local business and government leaders, media conglomerates, international security consultants, sports federations, and that highly profitable non-profit headquartered in a château in Switzerland: the IOC. This rejection thus imagines and enacts new possibilities in which a city’s residents are more empowered and global networks of capital have to respect local residents’ wishes.

Final thoughts

From this study of anti-Olympic art, I believe these subversive graphics play two main roles in contesting the power of the Olympic Movement. They disrupt the IOC’s simple narratives and threaten its (fragile) claims to authority, insisting instead on the “right to look” elsewhere. By rejecting top-down visuality, the graphics also imagine and enact new alternative possibilities in which a city’s residents have more local power relative to global networks of capital.

Now when I see the five rings looming over sports events, I see them as a frame ready for millions of global viewers to attach their interpretations. I’m sure there are still many nine-year-olds for whom those rings provoke excitement and awe. I’m sure there are folks of all ages who feel that way. But there’s a growing and increasingly vocal group of people around the world who associate the rings with oppression and an abuse of power, including nine-year-olds who have been displaced from their homes in the name of the Olympics. There’s a growing group of people who are eager to disrupt the five rings’ claims to peace and humanity. For all it can legally declare its ownership rights over those five circles, the IOC does not — and cannot — own those rings.

Academic references

Dery, M. (2017). Culture jamming: Hacking, slashing, and sniping in the empire of signs. In M. Delaure, & M. Fink (eds.), Culture jamming: Activism and the art of cultural resistance. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Mirzoeff, N. (2011). The right to look: A counterhistory of visuality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cerianne Robertson is a PhD student at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. She researches the news media narratives, discourses, and practices that sustain power relations, as well as the opportunities available to disrupt and change them. Her research often focuses on the stories we tell about cities and sports mega-events. Cerianne previously worked as the Editor and Media Monitoring Coordinator for RioOnWatch.org, a Rio de Janeiro-based media platform that aimed to amplify favela resident perspectives and monitor urban transformations in the build-up to the 2016 Olympics. She is currently a participant in NOlympics LA.