Review Essay: On ‘Making European Cult Cinema: Fan Enterprise in an Alternative Economy’ by Oliver Carter (Part 1)

/Today, I am sharing a review essay which Billy Proctor has written about a new book in the field of cult media studies. Proctor — an important cult media and fandom scholar in his own right — has been an invaluable help to me in supporting this blog this past year, including organizing the Cult Conversations series earlier this term. In this essay, he responds to some important but troubling critiques of the aca-fan tradition, clarifying some serious distortions in the work that has been done in the past and the arguments that have been made about why and how we study fans, including of course my own arguments about the nature of participatory culture. I certainly feel that there is room within any academic field for diverse perspectives, including very pointed critiques of the work which has come before. I have always welcomed critiques of my own work, since they often teach me to question assumptions, check my privilege, explore new directions, and nuance my language. Yet, I get frustrated when critiques over-simplify the arguments that were made in the past and in particular, treat the field (or for that matter, the thinking of individual scholars) as static and unchanging. So, I found Proctor’s essay as timely and provocative. I hope others will also find it so. in publishing this, I am not endorsing his position on this particular book which I have not read or its author who as far as I know I have not met, but I think it makes a useful contribution to the debates within and surrounding fandom studies. In the spirit of facilitating further conversation about these issues, let me formally offer Oliver Carter a similar opportunity to use this platform to respond to these critiques if he so wishes.

REVIEW ESSAY

‘Fancademia?’: On the Continuing Perception of Fan Studies as Celebrating ‘Resistance’ and Cult Media Studies as ‘Valorizing’ Trash Cinema (Part 1)

William Proctor, Bournemouth University (UK)

Oliver Carter. 2018. Making European Cult Cinema: Fan Enterprise in an Alternative Economy. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 226. ISBN: 978-90-8964-993-5

Undoubtedly, it is high time that more empirical work on cult fandom surfaced, and Oliver Carter’s new monograph is a welcome move into this area. Making European Cult Cinema: Fan Enterprise in an Alternative Economy aims to consider the way in which fan production should best be recognized as a form of entrepreneurship, an ‘alternative economy’ whereby fans create, write, produce, make, and sell ‘stuff,’ whether for profit or not, including “magazines, T-shirts, films or fan-produced DVDs” (62). This is unquestionably a valuable goal, but the mode by which Carter sets out his stall raises significant problems that I want to address extensively. I want to say, however, that there is certainly much value in approaching the concept of fan production as an alternative economic enterprise, with some practices shifting from ‘informal’ to ‘formal’ spheres, or skirting the imaginary boundaries between the two with some fluidity. I found it interesting that fans ‘resist’ legal parameters quite frequently, especially around copyright law, indicating that some activities would surely be deemed criminal by the copyright industries. Of course, many fans transgress, breach (or at the very least, test) the official borders of copyright legislation with associated practices (fan fiction, videoing, textiles, modding, filking, etc.); yet file-sharing activities are usually not as permissible as other kinds of transformative practices, and many people have been incarcerated for ‘pirating’ since the inception of home video. I shall return to the more valuable aspects of Carter’s book in the second part of this essay, but I firstly want to address the problems with the way in which the author sets out his stall at the beginning, which I read as highly charged, provocative and quite wrong.

Beginning with a stern attack on fan studies and cult media studies—and it is without question, an attack—Carter sets out his stall with an acerbic polemic. As I’m sure is true of many scholars, I often enjoy heady critical stances, but on this occasion, I’m disappointed to say that Carter’s trenchant opening gambit is all gums and dentures, all bark and no bite. The main problem with Carter’s opening chapters is a puzzling non-engagement with recent academic literature from the past decade that would certainly force a strategic rethinking regarding the way in which the book’s opening argument is vigorously presented. Scrutinizing the bibliography, I was astonished that key literature in relation to fan labor and the commodification of fan production is not addressed in any meaningful way, literature that would in no uncertain terms take the wind out Carter’s sails, be that in fan studies, cult media studies, or across cogent disciplines. Naturally, we all miss literature and we can’t always read everything that is out there on whatever the topic may be. (I certainly have, much to my embarrassment.) But Carter does not simply miss an article here or a book there, but dozens upon dozens of pieces published since at least 2006. Ultimately, Carter’s central argument is a house of cards, a castle made of sand. As Carter does not mince his words, then neither shall I.

The opening chapter argues that fan studies and cult media studies are being held hostage by fans who are also academics, whereby the identity of the ‘scholar-fan’ has been reversed into ‘fan-scholar,’ which were never clear binaries in any case but complex composites as argued by Matt Hills in the seminal Fan Cultures (2002). In this way, Carter ultimately constructs a homogenous portrait of a discipline that is almost three decades old at this point (I am speaking to fan studies first and foremost here, but shall return to what Carter terms cult media studies later). Chapter One’s first line may have many scholars scratching their heads: ‘This book is an attempt to approach fandom from a perspective that has been surprisingly neglected: an economic perspective’ (17). Carter goes on to complain that fan studies ‘has been shaped by what I term “fancademia”, a product of the blurring of roles between fan and academic that has emerged out of a body of work that has sought to celebrate fandom’ (17). Rehashing old arguments— and stop me if you’ve heard this one before—the author roundly accuses Henry Jenkins, Camille Bacon-Smith and Constance Penley for championing and celebrating fandom as a cultural activity, as an act of symbolic resistance, their collective crime being that they did not recognize that fan productions are always economic activities, even if they do not come with an underlying profit principle. This is what Carter means by ‘a celebration of fandom’ (55), or the clunky ‘fancademia’; that is, the understanding of ‘fan production as an act of symbolic production’ is reductively a celebration and only that—although Carter also admits that he understands the reasons why foundational work in fan studies focused on rescuing the figure of the fan from pejorative ‘Get a Life’ stereotypes hinged on the asexual, anti-social fanboy, dwelling in his parent’s basement while sporting Spock ears, wearing superhero unitards and swinging replica lightsabers on a daily basis. But the discipline has surely moved on since then, although that foundational element certainly still remains (not that there’s anything wrong with it). Oddly, Carter sometimes accepts that more recent work is beginning to emerge that redresses this offence, but ‘more recent’ for the author includes publications from anywhere between 2001 and 2015. (I’m not sure if I’d say that almost two-decade old literature is ‘recent.’)

And therein lies the rub. Carter’s sweeping attack on fan studies might have made at least some sense in the nineties, or early noughties, in relation to what Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss and C. Lee Harrington labelled the ‘first wave of fan studies’ in the first edition of Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World (2007). Although Carter cites this book, it is telling that it is only the first edition, and not the (2017) second edition that contains new chapters and sections focused on ‘Fan Politics and Activism’ (255-332) as well as ‘Fan Labor and Fan-Producer Interactions’ (333-419), which amounts to well over 100 pages of literature not engaged with at all. In the revised introduction to the second edition, Gray et al make clear that the first wave of fan studies was indeed ‘the fandom is beautiful phase,’ which ‘was primarily concerned with questions of power and representation’ (2), whereas the second phase ‘moved beyond the “resistance/ incorporation paradigm”’ (5). Indeed, as recounted by Gray et al, fan studies has gone through second and third waves, and is now arguably entering a fourth wave that we might refer to as the ‘fans-behaving-badly’ phase, with work on ‘toxic geek masculinity’ (Bridgett and Blodgett 2017) and ‘toxic fan practices’ (Proctor and Kies 2018) gathering apace, although these are by no means the first academic work to consider sexist, racist and/ or homophobic fan and ‘anti-fan’ discourses (see for example Brooker 2001; Busse 2013; Click 2009; Gray 2003; Jones 2015). Yet, to be honest, I firmly believe that fan studies is not easily reduced to distinct ‘phases’ any longer, as the discipline now includes so many different objects of study, conceptual approaches and theoretical currents that multiple discursive threads are in operation simultaneously (although I have argued in the past that fan studies is largely dominated by ‘geek’ objects, thankfully this is also changing rapidly). And while it might seem that I am out to defend the honor of an embattled fan studies, this could not be further from the truth. The vast majority of scholars would surely agree that the first wave of the discipline tended towards optimistic analyses and appraisals of symbolic resistance, but that counter-argument has been well represented and documented since at least Matt Hills’ seminal Fan Cultures, which is approaching its twentieth anniversary. Cornel Sandvoss, for instance, devotes an entire chapter to criticizing fan studies’ ‘dominant discourse of resistance’ (2005, 11-43) in Fans: The Mirror of Consumption.

Henry Jenkins has become somewhat of an easy target for scholars who do not seem to have engaged with his significant oeuvre beyond the seminal Textual Poachers (1992) and Convergence Culture (2006). Interestingly, Carter accepts that Jenkins no longer sees fan activity as ‘a form of resistance’ (44) in Convergence Culture, but goes onto include multiple academic criticisms of that work without considering the various responses and clarifications that Jenkins has supplied in the thirteen years since its publication (see for example Jenkins 2014). Yet, to claim that Jenkins has not spoken to the economics of fan production in a non-celebratory way, or the asymmetrical tensions between production and consumption, is not only myopic, but incorrect. In the second edition of Convergence Culture:

Those of us who care about the future of participatory culture as a mechanism for promoting diversity and enabling democracy do the world no favor if we ignore the ways that our current culture falls short of these goals. Too often, there is a tendency to read all grassroots media as somehow ‘resistant’ to dominant institutions rather than acknowledging that citizens sometimes deploy bottom-up means to keep others down. Too often, we have fallen into the trap of seeing democracy as an ‘inevitable’ outcome of technology change rather than as something which we need to fight to achieve with every tool at our disposal. Too often, we have sought to deflect criticisms of grassroots culture rather than trying to identify and resolve conflicts and contradictions which might prevent it from achieving its full potential. Too often, we have celebrated those alternative voices which are being brought into the marketplace of ideas without considering which voices remain trapped outside (Jenkins 2008, 293-294, emphasis added).

And elsewhere:

Convergence Culture may place its emphasis on the growing influence of customers, audiences, fans, citizens, within this networked culture, but whatever ground they have gained has been in the face of new efforts by corporate producers to ‘manage’ and, yes, ‘manipulate’ these same groups (2014, 279).

It is possible, I think, that scholars may suggest that Jenkins sees the the blurred lines between producers and fans in the media convergence age as more symmetrical and less dialectical than they actually are, but he has emphasized the production/ consumption imbalance on several occasions. Jenkins does not promote the idea that the affordances of the new media landscape have led to a full democratization of the production/ consumption dialectic, but he is interested in how new tools and portals support a push towards that goal. In Spreadable Media (2013),for instance, Jenkins and his co-authors, Sam Ford and Joshua Green, discuss the moral economy in relation to online fan practices and productions being enveloped within ‘the corporate capitalization of free labor’ (87), but they also recognize that the

frictions, conflicts, and contestations in the negotiation of the moral economy surrounding such labor are ample evidence that audiences are often not blindly accepting the terms of Web 2.0…We feel it is crucial to acknowledge the concerns of corporate exploitation of fan labor while still believing that the emerging system places greater power in the hands of the audience when compared to the older broadcast paradigm (58).

Jenkins, Ford and Green are also

certain our focus on transformative case studies or “best practices” throughout may be dismissed by some readers as “purely celebratory” or “not critical enough,” we likewise challenge accounts that are “purely critical” and “non-celebratory enough,” that downplay where ground has been gained in reconfiguring the media ecology. We believe that media scholarship needs to be as clear as possible about what it is fighting for as well as what it is fighting against (xii).

‘We are nowhere near equality at the present time,’ argues Jenkins elsewhere, ‘but there have been shifts in the relationships between producers and consumers…No one can really control what happens to media content once it reaches the hands of the consumer, but consumers have had difficulty influencing production decisions’ (in Chudoliński 2014). Indeed, ‘tapping free labor for economic profit can turn playful participation into alienated labor’ (Jenkins, Ford and Green 2013, 65).

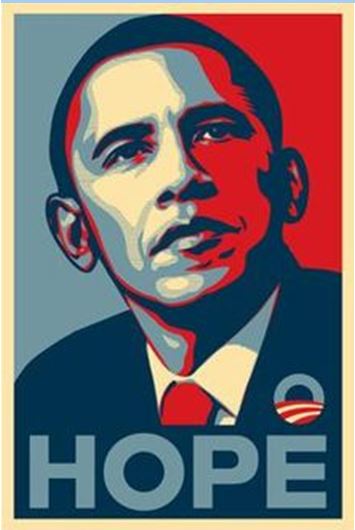

I could go on, but the point has been made, I should think. What seems to have been Jenkins’ major crime—and I’m not only speaking about Carter on this point, but the general image of fan studies in the academy—is his embrace of a politics of hope, and an emphasis on the way in which fan cultures might well be able to enforce, or at least encourage, profound shifts in the media convergence era—shifts which have without doubt already occurred (although not symmetrically nor democratically). More recently, Jenkins has turned to consider fan activists and citizens through his conceptualization of the ‘civic imagination,’ whereby fans ‘geek out for democracy,’ examples of which include the Harry Potter Alliance, and the Occupy Wall Street Movement, among others (see Jenkins et al 2016). This is not to imply that Jenkins isn’t optimistic—he is certainly that—but that shouldn’t necessarily be a terrible thing, especially when qualified transparently (which Jenkins has done time and time again). But I would argue that viewing his work as unabashedly celebratory and romantic is to do a disservice to his extensive oeuvre and, consequently, the entire discipline of fan studies. It is certainly no mean feat to criticize not only a single scholar but an entire field, especially when such claims are easily deflected.

To consider Carter’s sweeping claims about ‘fancademia’ as a utopian celebration of fan production as ‘resistance’ that has not yet convincingly approached the production/ consumption dialectic is not only wrong, but also disingenuous. And let me reiterate: it is the rhetorical force and confidence with which Carter communicates that is questionable, as well as his tendency to make multiple declarative and definitive statements that leave the author with no room for maneuver, not that I am suggesting that criticism should not be made (I’m making one now, after all). That should be par-for-the-course for scholarly debate and discussion (and academia is a discursive field built out of patterns of agreement, disagreement, revisions, conceptual shifts and empirical evidences, etc.) Yet again, the problems with Carter’s claims-making and rhetorical posturing is that they are so easily overturned, or at the least problematized, by extant literature.

Consider a series of edited issues in the journal Transformative Works and Cultures, such as Nancy Regin’s ‘Fan Works and Fan Communities in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (2011); Francesca Coppa, Muhlenberg College, and Julie Levin Russo’s ‘Fan/Remix Video’ (2012); Mel Stanfill and Megan Condis’ on ‘Fandom and/ as Labor’ (2014); and Bob Rehak’s ‘Materiality and Object-Related Fandom’ (2015). Even taking this single journal alone, many of the articles in these edited issues touch upon the political economy of fandom as well as continuing analyses in a cultural sense, an approach that Carter claims is his own. I would definitely expect much of this work to be drawn upon, discussed, deliberated, embraced, developed or rejected.

There is also Kristin Busse’s edited section in Cinema Journal, ‘Fandom and Feminism: Gender and the Politics of Fan Production,’ in which several scholars engage with female fans who ‘feel a deep sense of community and are engaged in a complex subcultural economy—using work time to write about copyrighted characters, teaching one another how to use complex technological equipment to create zines for free, and so on’ (2009, my italics). Although Carter’s understanding of a fannish ‘alternative economy’ is also not solely underpinned by the profit potential, to which he challenges John Fiske in the book’s Preface and elsewhere as a ‘problematic’ assertion (15), he sees ‘a far more complex economy where fans are involved in acts of enterprise, which includes the production, distribution and consumption of artefacts,’ and that ‘these artefacts are exchanged either as gifts or commodities’ (40). In other words, even fan productions that are distributed free-of-charge are not really free as they ‘can [be] exploited by others, for economic gain’ or as part of reciprocal exchanges (56). Busse also considers that ‘commercial interests become complicated as a gift economy questions capitalist models of labor and exchange while nonetheless participating in them in various ways’ (2009, 196) and ‘an unequivocal embrace of noncommodified work remains problematic within a world that requires paying the bills’ (107); while in the same issue, Karen Helleckson states that: ‘Online media fandom is a gift culture in the symbolic realm in which fan gift exchange is performed in complex, even exclusionary symbolic ways that creates a stable nexus of giving, receiving, and reciprocity’ (2009, 114). What is immediately striking is that we know that Carter is aware of this work as he cites Helleckson (2015) briefly, but fails to engage with the rest of the contents. The same could be said of Busse’s (2015) ‘Fan Labor and Feminism: Capitalizing on the Fannish Love of Labor,’ again for Cinema Journal, but no such luck. Jenkins, Ford and Green also repudiate the notion that the fannish ‘gift-economy’ is entirely free, but also, as Carter argues similarly, entangled in commodity culture whereby ‘their exchange is governed by social norms rather than contractual relations’ which ‘circulate through acts of generosity and reciprocity’ (2013, 67). Yet Carter maintains that ‘recent work tends to romanticize the concept of the gift economy’ (56) despite the fact that he largely says the same things.

Analyzing the complex interrelationship between production and consumption between fandom and e-commerce, Josh Stenger demonstrates the collision between the Fox Corporation and fans when Buffy The Vampire Slayer props, clothing etc., from the TV series were auctioned on E-Bay, compelling scholars to ‘reconsider the dimensions and boundaries of fan devotion, desire and consumption on the one hand, and of producer-fan relations on the other’ (2006, 40). More recently, Brigid Cherry’s monograph, Cult Media, Textiles, and Fandom (2014), clearly evidences the commodification of fan handicrafts for profit (knitwear and so forth), with fans converting symbolic capital into economic capital, thus forming what Cherry terms ‘a micro-economy’ through e-commerce transactions on websites, such as Etsy. I would certainly think that Busse’s ‘complex subcultural economy,’ and Cherry’s ‘micro-economy,’ should not only have been consulted, but would actually help support and refine Carter’s ‘alternative economy’ concept, as well as the litany of other work in fan studies over the past decade-and-a-half that unequivocally consider the production/ consumption dialectic as it pertains to fan labor and other factors (see also Bakioğlu, 2016; Ball 2017; Brooker 2014; Cherry 2011; Chin 2013; Chin 2014; Goodwin 2016; Helleckson 2015; Kozinets 2014; Lothian 2009; Lothian 2015; Milner 2009; Olds 2015; Sandvoss 2011; Scott 2009; Scott 2015; Stanfill 2015). To make the assertion that fan studies has not yet moved on from narratives of symbolic resistance nor considered labor and the commodification/ economics of fandom is not only specious, but patently ludicrous.

Furthermore, Carter argues that the fan studies turn, and the romanticized understanding of fans as ‘resistant’—which is always a symbolic resistance, not an economic one, which is of course what gets Carter’s goat—emerges out the Birmingham School’s CCCS and the shift towards studying popular culture as a site of struggle through the adoption of Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony. But even here, Carter misreads Gramsci and the CCCS’ applications of hegemony, which is emphatically not only about resistance, but also, in Gramsci’s terms, incorporation. To be sure, the CCCS aimed to move the conversation away from Frankfurt School pessimism—and rightly so—but drawing upon Gramsci to illustrate culture as a site of struggle and symbolic (and often subcultural) resistance worked not to celebrate popular culture as the expense of the economic, but to indicate the dialectical tension between forces of production and consumption, between resistance and incorporation. Carter’s criticism of Dick Hebdige stands out as a gross misreading, considering that Hebdige articulated very well that processes of subcultural symbolic resistance would invariably be incorporated and subsumed within capitalist processes—until the process starts all over again, naturally. In a section titled ‘Two Forms of Incorporation,’ Hebdige explores ‘the conversion of subcultural signs (dress, music, etc.) into mass-produced objects (i.e. the commodity form)’ (94). Subcultures strike ‘their own eminently marketable pose’ (93), which will always eventually be converted and commodified into capitalist modes of production.

Indeed, the creation and diffusion of new styles is inextricably bound up with the process of production, publicity and packaging which must inevitably lead to the defusion of the subculture’s subversive power – both mod and punk innovations fed back directly into high fashion and mainstream fashion. Each new subculture establishes new trends, generates new looks and sounds which feed back into the appropriate industries (95). Thus, as soon as the original innovations which signify ‘subculture’ are translated into commodities and made generally available, they become ‘frozen’. Once removed from their private contexts by the small entrepreneurs and big fashion interests who produce them on a mass scale, they become codified, made comprehensible, rendered at once public property and profitable merchandise […] This occurs irrespective of the subculture’s political orientation: the macrobiotic restaurants, craft shops and ‘antique markets’ of the hippie era were easily converted into punk boutiques and record shops. It also happens irrespective of the startling content of the style: punk clothing and insignia could be bought mail-order by the summer of 1977, and in September of that year Cosmopolitan ran a review of Zandra Rhodes’ latest collection of couture follies which consisted entirely of variations on the punk theme. Models smouldered beneath mountains of safety pins and plastic (the pins were jewelled, the ‘plastic’ wet-look satin) and the accompanying article ended with an aphorism – ‘To shock is chic’ – which presaged the subculture’s imminent demise (96).

Indeed, as the Birmingham School’s David Morley said during fan studies formative year: ‘The power of viewers to reinterpret meanings is hardly equivalent to the discursive power of centralized media institutions’ (1992, 341). Of course, we could also add Stuart Hall’s encoding/ decoding model, a framework which understands audiences as reading media texts from three positions: dominant, negotiated or oppositional. (Although I would hope many fan and audience studies scholars note the limitations of Hall’s three reading positions as in no way a satisfactory model to capture the gamut of audience interpretation and evaluation).

What is more frustrating is that Carter fails to recognize the principle of Gramscian hegemony in the first instance, but then embraces it in a later chapter without query. Drawing on Peter Hutchings, Carter explains how

early fan production was an act of ‘resistance,’ such as the ‘grimy’ fanzines and bootleg videos that were distributed as a response to the video nasties panic…then identifies how this oppositional fan activity has been replaced with ‘handsomely’ produced books and special edition DVDs and Blu-Ray releases…This book furthers Hutchings’ discussion of these practices to investigate the cultural and economic processes that led to the development of a fan-produced alternative economy relating to European Cult Cinema (91).

Here, Carter effectively embraces an understanding of fan production as hegemonic in the Gramscian sense of the term; as a dialectical process of resistance and incorporation, much in the same manner of Hebdidge and other Birmingham School scholars. Hutchings may not use the term, but that is unquestionably an explanation of hegemonic processes writ large. As noted above, the second wave of fan studies has largely moved on from the resistance/ incorporation paradigm, and Gramsci may have been silenced in media and cultural studies generally, or at least quietened, perhaps because of the ‘bad smell’ associated with Marxist thought since the poststructural/ postmopdern turn, but I strongly believe that it is high-time we return to Gramsci once again, a sentiment that has in the past been proposed by others, such as Angela McRobbie calling for ‘an extension of Gramscian cultural analysis’ (1994, 39; see also Hills 2005). Fan studies scholars may not adopt the term any longer, but the dialectical tensions between production and consumption are all over the field. (I would even argue that Jenkins is a closet-Gramscian.) With that said, Dan Hassler-Forest’s Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Politics: Transmedia World-Building Beyond Capitalism (2016) convincingly illustrates the strength of dialectical approaches that do not romanticize the ‘power’ of fan audiences, which are ‘a seductive illusion’ in any case in Hassler-Forest’s account (17), whereby fannish ‘immaterial labor’ is easily ‘reterritorialized’ and co-opted back into the cash nexus of global capitalism, demonstrating ‘clearly that the relationship between producers and audiences is still a hugely asymmetrical one, and that the power of media conglomerates remain a massive obstacle for actual media democratization’ (15). For Gramsci, ‘a certain equilibrium’ is maintained between the contradictory and complex forces of resistance and incorporation as a dialectical struggle. However, that relationship is always asymmetrical, although ‘sacrifices of an economic-corporate kind’ are ‘such a compromise cannot touch the essential’ (Gramsci 1978, 161)”—the ‘essential’ being power (‘political-ethical’) and the underlying principles of the capitalist mode(s) of production (‘the cash-nexus’).

ANTONIO GRAMSCI

That said, Carter does admit that a political economy approach on its own effectively imposes limits on the agency of fan activities—and of course he is not the first to do so by an enormous margin—but when the author suggests that a fusion of cultural and political economy theory is absent from the studies he excoriates, I found this claim astonishing, not least because the utilization of Gramsci’s hegemony theory by cultural studies pioneers is exactly that—an understanding of culture and economics as dialectically intertwined, entangled and impossible to isolate as separable factors (see also Johnson 2014). In fact, one of Carter’s frequently used sources, the seminal Fan Cultures (Hills 2002), absolutely made this explicit almost twenty-years ago, although for Carter, Hills did not go far enough (a fair assessment, I would say). Yet, Hills did propose a viewpoint that saw fans as engaged in a tug-of-war between the Scylla and Charybdis of the ‘resistance/ incorporation’ dialectic, and that fans are in many ways ‘ideal consumers’ that at the same time, often espouse anti-commercial rhetorics, suggesting that ‘cultural power cannot be located in any one group, nor can it be viewed as the product of a singular system’ (2002, 44). Indeed, it would certainly seem that Carter rightly shares this view, arguing that a political economy approach on its own would rob fan cultures of agency, a viewpoint that is precisely what the cultural studies project has argued since its inception.

As a result, Carter’s ‘reconceptualization of fandom’ as ‘a cultural and economic activity’ is less a reconceptualization than a reification and reaffirmation of what many scholars have been saying for years at this point, going back to the bedrock of cultural studies (and I would also add audience and reception studies to the mix given that borders between disciplines are not permeable but porous). But it is the force with which Carter states these things that is perhaps most disappointing, in sentences such as: ‘it is academic work on fan production that has become a minor activity’ (30). It is not that Carter’s approach is myopic—although it is certainly that by the manner with which it reductively constructs fan studies as a homogenous and unvarnished celebration of fan production—it is as if the author has ignored or cast aside any and all argumentation that would certainly encourage a thorough rearticulation of the way in which his rhetorical insistence on distinction and originality is enacted confidentially, authoritatively and, to be quite frank, bullishly and boorishly. To complicate matters further, Carter seemingly undermines his own argument several times by referring to ‘how this early period of research celebrated fandom’ (28); ‘that solely viewing fans as resistant is problematic’ (26); ‘new models for studying fandom’ were inaugurated by Matt Hills (2002) and Cornel Sandvoss (2005); and that an ‘area of academic research that is currently addressing the economy of fandom is that related to anime fandom’ (38)—'current’ in Carter’s account meaning literature between 2005 and 2011. I agree that ‘solely viewing fans as resistant is problematic,’ but that is neither a new insight nor an original intervention given that Carter’s book was published in late-2018. But the contradiction laid out bare for all to see is that Carter’s disgruntlement is attributed to an ‘early period of research,’ and as, a result, is an argument that is at least a decade too late, perhaps even longer.

(Full bibliography in part 2)

___________________

William Proctor is Senior Lecturer in Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He has published widely on matters pertaining to popular culture, franchising and fandom, including comic books, film and TV. William is the co-editor of Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman for Routledge), Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Richard McCulloch for University of Iowa Press), and the forthcoming edited collection Horror Franchise Cinema (with Mark McKenna for Routledge). At present, William is completing his debut single-authored monograph Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia for publication in 2019/20 (for Palgrave).