Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Arely Zimmerman & Andres Lombana (Part I)

/Arely

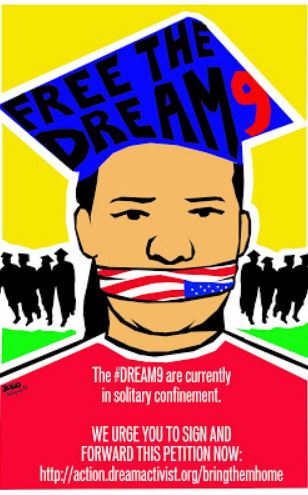

My interest in participatory politics is connected to my work in immigrants’ rights movements in the United States, and more specifically, the activism of undocumented youth from the 2007- to the present. This activism was initially focused on achieving immigration reform and passing the DREAM Act, but has now shifted its focus on challenging U.S. immigration enforcement and detention policies. When I initially began my research with MAPP (Media Activism and Participatory Politics), I focused on the liberatory potential of youth’s engagement with digital and social media. I argued that by mastering these new technologies, youth were able to shape the immigrants’ rights agenda for a decade.

However, with the rise of Trumpism, the initial optimism about new media has waned. For youth, the hard-won victory of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), which granted a limited protection from deportation, was followed by the election of Trump, the rescinding of DACA, and the attacks on Sanctuary cities and campuses across the country. New media technologies, which were once presumed to be emancipatory (for better or worst), have become the primary tools of authoritarian white supremacist rule. Trump uses twitter extensively to set and frame his agenda, to degrade members of minority groups, to circulate false ‘news’, and to shape mass public opinion on immigration. On the other hand, the “coming out” stories that young people used to humanize the immigration issue have become obsolete. Young people realize that immigrants are surveilled and activists are monitored under the watchful eye of Big Brother. Under this new regime, many activists abandoned more public sites like DreamActivist. They went “underground”. Civil disobedience actions- while still in use- have also waned. What does this say about participatory politics? Well, what it shows us is we have to seriously consider how these new technologies are being used in anti-democratic ways. We also have to consider that participation is a privilege of citizens- primarily white citizens- in this context. While communities of color and immigrants still use social media to document harassment, hate crimes, etc., the risks of “coming out” using social media are too high a price to pay. Like a colleague of mine writes, undocumented youth’s activism is now defined by the refusal to speak.

Andres

Hola Arely! Your research on immigrants’ rights movements in the U.S. and youth activism sounds fascinating. It is a crucial theme that is at the center of political debates in several countries, particularly in the U.S. with the context of a demographic shift that touches all social dimensions. The educational dimension is perhaps the one I am more familiar in this space, since I had the opportunity of studying and working with Latinx immigrant youth for several years while doing my PhD and living in Austin, Texas. Through several ethnographic and action research projects in public schools, community organizations, and creative collectives, I experienced, first hand, the current transformation of the U.S. population and the challenges that many Latinx youth confront as they try to actively participate in the culture, economy, and politics of a rapidly changing society. Studying how this youth population leverages digital tools and networks for learning and developing career trajectories allowed me to better understand how digital inequalities have evolved, and how beyond access to technology and gaining digital skills, it is critical that minority and non-privileged youth also have access to social and cultural capital. First and second generation Latinx immigrant youth that grow up in working class home environments, poverty contexts, and attend low-income public high schools usually have limited access to networks of support that are rich and diverse in social and cultural capital. That fact creates barriers of participation (in culture, politics, economy) that are more difficult to overcome than the ones of material access to technology and skills. That was one of the findings from the ethnographic work I conducted with the Connected Learning Research Network’s Digital Edge team led by Craig Watkins at a public high school and one of the central themes I explored in my dissertation. (see the Doing Innovation website here).

The optimism on the liberatory potential of new media technologies has decreased in recent years as the political climate has changed not only in the U.S. but also in several countries around the world. The world wide web just turned 30 years old last month and, although we have seen it as a generative space of innovation, democratization, and activism, we have also become more aware of its transformation into a space of surveillance, harassment, data exploitation, market concentration, and disinformation. Moreover, as you point out, what used to be considered emancipatory tools for marginalized and oppressed populations have also turned out to be the tools for radical, supremacist, far right movements and governments. In Latin America, for instance, we have seen how a powerful radical right movement successfully has leveraged social media such as Facebook, Whatsapp, and Twitter, for spreading disinformation and misinformation, creating political polarization, and ultimately, winning elections (e.g. 2018 presidential elections of Colombia and Brasil). In the Colombian case, that is the one I am more familiar with, the new right-wing government and its far-right party have used these tools and networks to undermine the implementation of a peace deal that was signed in 2016, the transitional justice process, and the construction of an inclusive and plural historical memory of the armed conflict (the oldest in the Americas with more than 60 years). Such memory building process was at the core of the peace process that took place between 2012-16, and helped to empower several minority groups victims of war (e.g. women, youth, afro-colombians, and indigenous populations) with digital tools for telling their stories with their own voices, documenting their territories, and advocating for their rights. Memory is a contested space in a country where there is no consensus about peace, justice, and the transition to a post-conflict scenario. Digital tools and networks, in such context, can also be leveraged to exacerbate the polarization and construct a historical memory that is exclusionary.

As we confront a moment of crisis in participatory politics and democratic processes, both conservative and progressive movements are leveraging "any media necessary" for getting into power and pushing their agendas. Their communication strategies involve using both old and new media, and both public and private platforms. Private messaging tools like Whatsapp, for instance, have become one of the most effective media in Latin America and other parts of the so called Global South for spreading news, photos, videos, music, and any kind of digital content. The private and encrypted quality of Whatsapp has made this platform a productive spaces for both far-right radicalization, and progressive and social justice organizing. I wonder to what extent the youth activists in the U.S. that "have gone underground" after the 2016 elections are leveraging encrypted communication tools in order to avoid being tracked. What kind of technology infrastructure is supporting their move to the underground? How has this move changed their communication tactics?

Arely

Thank you Andres for your response. I would like to clarify what I mean by “going underground” and be more specific about the kind of media they are leveraging in response to your query.

I will answer your question by recalling the 2016 elections and its aftermath. The day after the election, I met with students to reflect and strategize about how to move forward. At the time, the college where I was teaching was trying to implement a set of institutional responses to mediate the harmful effects of any policy changes ushered in by the new administration. I served as an advocate for undocumented and DACAmented students. DACAmented students were particularly afraid that by applying for DACA they had put their parents in harm’s way essentially handing over information on their addresses, etc. While my college wanted to do the “right thing”, they failed miserably to make students feel safe. They rejected appeals to declare their campus a sanctuary campus, they failed to commit to not working with federal agents if they came on campus, and they also were slow in finding ways to fund students when their DACA work permits expired. All of this uncertainty mobilized students to action. Rather than hide, they staged a direct action on campus. Yet, they also made a conscious decision to use SIGNAL instead of SMS to communicate with me and each other. Students felt a new sense of vulnerability and fear of surveillance, even from their would-be allies.

Many of my students had been active in the national immigrants’ rights movement and the public campaigns for the DREAM Act. Going “underground” also meant being more strategic about sharing their stories on public platforms to wider audiences. Even though my students engaged in one direct action on campus, they were less willing to engage in forms of civil disobedience off campus. They were also less willing to use blogging/vlogging to reveal their status online, as had been the repertoire of contention from about 2007-2015 (and that I write about in an article in IJOC).

Another departure from the past was students’ hesitation to speak in front of cameras. On the day of the direct action on my campus, reporters asked for interviews with participants and they nominated a U.S. citizen to speak for them. This was a departure from the past when undocumented youth were adamant about speaking for themselves.This signaled that the political context (as well as the political opportunities) had changed under Trump. Activists navigated these contexts in different ways. I don’t necessary think that their refusal to speak publicly meant that their activism also stopped. It simply meant that it would be channeled in different ways, and that the risks of using social media outweighed the benefits.

Now I’d like to circle back to some of the insights you provided in your post. I am very intrigued by your findings that:

First and second generation Latinx immigrant youth that grow up in working class home environments, and attend low-income public high schools, usually have limited access to networks of support that are rich and diverse in social and cultural capital. That fact creates barriers of participation (in culture, politics, economy) that are more difficult to overcome than the ones of material access to technology and skills.

This makes me think of the students/youth we interviewed for the MAPP (Media, Activism and Participatory Politics) project with Henry Jenkins. Those activists were first gen Latinx students from very low income high schools but had overcome some of these barriers to participation. I speculated that it was their access to “other” forms of capital- for example, the presence of student groups/organizations on their campuses, mentors/teachers who were connected to immigrants’ rights groups, and “contextual” capital in their local neighborhoods (mainly in Los Angeles) with a history of activism that propelled these students to movement participation. Undocumented student activism is particularly rich to study given that social capital is so important for political participation and all indicators would point to it being low for these students. What do you think?

Andres

Yes, I totally agree that accessing "other" forms of capital is critical for overcoming barriers to participation. I do believe that has been the case for many of the first gen Latinx students that have moved up in the socioeconomic and educational ladder in the U.S. Moreover, being able to connect to organizations that support immigrant and Latinx communities, and that keep the longer histories of immigrant rights alive in a local context can be super empowering for youth. Geography and local context matter for all kinds of participation. Although it is true that the Internet and the networked communication environment have made physical distance irrelevant for several processes and allowed people from any part of the world to connect and collaborate, geographic proximity is still relevant. Particularly for accessing certain forms of capital such as social and cultural one, it is crucial.

In contrast to the first gen Latinx students you interviewed in L.A., none of the Latinx students (all of them Mexican-Americans) I encountered at Freeway High School in Austin, TX, connected to local community groups such as immigrant rights movements or to ethnic organizations that could help them to expand their social and cultural capital and to diversify their networks. Their school and households were located in a suburban area of Austin, far away from the inner city and disconnected from the neighborhoods of vibrant cultural and economic activity.

Surrounded by food deserts, with limited recreational areas, and with precarious public transportation, this area had experienced a process of povertization in the last decades similar to the one of other American cities. Growing up in working class Mexican immigrant families, attending a low-performing school, and living in a suburban poverty context, made access to social, cultural, educational, and other resources difficult for this youth.

Despite having access to mobile phones and networked computers at home, and developing a range of new media literacy skills, many of the Latinx students I met at Freeway High remained disconnected from opportunity. Paradoxically, although they were proud about living in Austin, identified with the creative and high-tech ethos of the city, and wanted to follow careers as filmmakers, fashionistas, and game designers, most of them could not follow the pathways they dreamed, partly because their lack of access to diverse networks of support, mentors, and cultural and social capital.

_____________

Arely Zimmerman is Assistant Professor of Chicano/a Latino/a Studies at Pomona College in Claremont, California.

Andres Lombana-Bermudez (@vVvA) is an assistant professor of communication at the Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, Colombia. He is also an associate researcher at the Centro ISUR at the Universidad del Rosario, and a fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University.