Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Andrew Scrock & Moritz Fink (Part II)

/Andrew:

I appreciate how you and Marilyn are reviving culture jamming! It is a valuable concept that helps us understand how using cultural symbols originating in corporations can be wielded for expressly political purposes. I’ve been slowly collecting zines and guides, like The Art and Science of Billboard Improvement and Advertising Shits in Your Head that describe ways to reclaim public space. Being post-“cyberspace” has (thankfully) returned us to question how urban infrastructures can be hacked and repurposed. The Simpsons also brings us back to Henry’s foundation in thinking about how popular culture can provide the vocabulary for political self-expression and identity work. Many of the civically-minded geeks I’m following sometimes refer to themselves as “civic technologists” – and I simply call “techies” – do both of these things. They work on civic infrastructure and try to organize by using symbols drawn from popular culture. For example, they are organizing to build and encourage adoption of services that improve the way low-income families get food assistance and enable residents to buy lots of land in their neighborhood for a dollar and develop them for their community. Because their work is arcane and difficult, they will never be a social movement like Black Lives Matter. Rather than their mobilization, techies face different challenges, like how to create and share a collective political identity for infrastructural politics that resists absorption into bureaucracy.

Jake Brewer Imagined as a Rebel Pilot

Popular culture is part of the ways techies shape and share a political identity, such as borrowing from transmedia franchises like Star Wars. One of the first techies to use symbols drawn from popular media was Jake Brewer, a political insider I write about in my book “Civic Tech.” Jake rose to prominence through the Sunlight Foundation and joined the White House as a Senior Technology Advisor, before working on immigrant rights. He frequently referred to techies as the “rebel alliance,” a concept that allowed them to think of themselves as outsiders even as they worked inside government to improve it. To Brewer, the Empire symbolized everything that government should not become: an authoritarian state that ignored the will of the people. Tragically, he was killed in a charity bike ride. After his death, pins were made that showed Brewer in the cockpit of an X-Wing fighter. “He saw the American revolution as unfinished,” wrote Micah Sifry, “and believed that techies and open democracy activists were indeed part of the continuing #RebelAlliance fighting the Empire.” Brewer still serves a touchstone for the identity of techies because he was an astute political maneuverer who managed to both keep his deeply-held convictions and build collaborations inside of government. You also can see Star Wars imagery in the unofficial US Digital Services mascot, Mollie the crab, and tweets by their cousin department, 18F.

Applying a lens of media activism and culture jamming can also help us understand the current backlash against tech companies that surveil, classify, and sell the data of users. The video “Dear Tech” appeared as an advertisement during the Superbowl, bankrolled by IBM and viewed by over a hundred million people. In it, celebrities like Janelle Monae (the Electric Lady herself!) call for “AI that helps us see the bias in ourselves” and “Blockchain to help reduce poverty.” Watching this video, I was sympathetic to the ideas of reducing poverty and bias. The problem I and others saw was that the video read like a plea from individuals for more tech to solve the very problems that technology corporations produced. In response, a group of critics led by Joy Buolamwini of the MIT Media Lab (including friends of Civic Paths like Ethan Zuckerman, Safiya Noble, and Sasha Costanza-Chock) made a video that parodied this ad. Instead of “Dear Tech,” it was titled “Dear Tech Company.” It used the same facing-the-camera format and dramatic swells, while putting the pressure on tech companies to reform the way it collects data, listens to employees, and listens to the public.

In flipping the script, they added a new critique: technology companies, not just users, should change the way they operate and act politically, such as through lobbying and non-engagement with local communities. For an example of how these conflicts are playing out on the ground, see Molly Sauter’s sharp pieces about Sidewalk Labs/Google’s bid for Toronto’s Quayside. The original video encouraged us to think about technological problems as being solved by individuals clamoring for more but better technology. The remix encouraged us to recognize that unjust technologies mirror the organizational practices and corporate desires of their creators. I would go even further. Our obsession with reforming “big tech” says quite a bit about our collective inability to imagine a publicly-owned alternative. The techies I’m working alongside are involved in this very effort by reforming government services to be more equitable and just. There is a certain strain of “tech bros” out there that naively believe complex social problems can be alleviated with simple technological solutions. However, the idea that every geek is a “tech bro,” or that one drop of technology in a comprehensive reform strategy makes it “technocratic,” is incredibly dangerous. Our shared future civic life will probably involve technology. We need politically-aware, ethical, and organized political actors – most importantly, the builders and institutional boundary-crossers.

Mo:

Your example of techies appropriating Star Wars’ iconography is intriguing. Indeed, commercial culture – including pop culture products such as Star Wars or The Simpsons as well as brands such as Coca-Cola – has offered a wealth of imaginary worlds shaping popular mythologies, which are shared by millions of people all round the world. In this regard, the power of the symbolic must not be underestimated in political terms. By appropriating narrative storyworlds (e.g., Star Wars, The Simpsons) or corporate identities (e.g., Coca-Cola), activists equip themselves with a widely understood and appealing visual vocabulary to raise awareness for their causes, and to align with sisters and brothers in spirit.

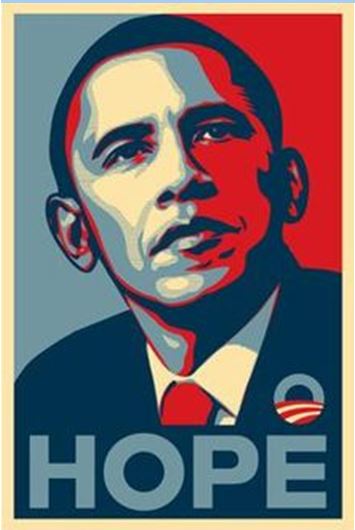

Consider Barack Obama’s 2009 election campaign, which was effectively propelled through pop art imagery – an important factor in creating the overwhelming Obama-hype as well as in fostering voter mobilization. One of the images circulating at that time, by the L.A.-based artist Mr. Brainwash, presented Obama in Superman getup in front of the American flag.

It’s a very patriotic motif and, at the same time, a great example of what the Civic Paths group has conceptualized as “civic imagination.” For many supporters, Obama was not so much a presidential candidate bound to political realities, as he was a symbol for a better, more just America. This messianic connotation was expressed by associating the Senator from Illinois with the utopian character of Superman. A similar desire for this messianic quality is visible in the iconic “HOPE” poster designed by street artist Shepard Fairey. Strikingly, the image’s visual style is not only reminiscent of a certain socialist “hero-aesthetic” in the vein of the famous Ché Guevara poster; moreover, “HOPE” exhibits an ironic twist achieved through a graphic sensibility that recalls Fairey’s portfolio as a professional graphic designer who previously conceived ads for companies such as Hasbro, Nike, and Pepsi.

This is to say, it seems insufficient to classify contemporary cultural productions into those originating from some kind of “bad” capitalist bloc à la the Frankfurt School’s culture industry and those emerging from some kind of “authentic” folk culture. The bulk of materialized culture will carry elements of both commercial and grassroots culture. To comprehend and decipher the ambiguities and particularities at work in a given cultural artifact is certainly one of the great challenges of the cultural experience today.

In that sense, the entrepreneurship of street artists like Shepard Fairey or Banksy may be viewed in contradiction to the political outlook conveyed in their works. Why? Because the cultural critic in us considers branding strategies, which have become somewhat intrinsic to our culture at large, to reinforce the capitalist ideology. But would Fairey’s or Banksy’s artworks have the same effect and impact without their propagandistic qualities? Certainly not. Culture jamming has typically adopted Madison Avenue’s strategies and repurposed the persuasive power of advertisements, especially since many culture jammers (like Fairey) have been professionally trained graphic designers themselves, many of which moonlighting at Madison Avenue. Conversely, the ad industry has imported culture jamming into its toolbox as forms of guerilla marketing, which doesn’t necessarily mean cooptation in the negative sense of the word. Take, for example, Crispin Porter + Bogusky’s anti-tobacco Truth campaign at the millennial turn – which was quite similar in style to Adbusters’ earlier anti-tobacco ads, as discussed by Michael Serazio in his contribution to our edited volume.

Repurposing elements of power – whether cultural, financial, or institutional – in a collaborative attempt to make this planet a “better world” suggests a link to the techie-activists you were talking about. Their affiliation with institutions may provide potentials of conflict with their political points of view. But, as I understand it, they’re looking for ways to execute a bread-and-butter job with an alternative work ethic. That is, whether they are critical of their employers’ institutional politics or not, they try to take liberties in favor of what they consider important in moral terms of the “common good.” This emancipatory approach in relation to the dominant capitalist culture by carving out micro-level “real utopias” – contexts where the “little man” is able to perform acts understood as bolstering change and resistance – reminds me of Michel de Certeau’s example of practices he calls la perruque (the wig). The term refers to employees carrying out work for themselves instead of doing work they’re assigned to by the employer. (Needless to say, tasks meant to promote the common good may ultimately be more valuable in a civic context than to aimlessly surf the web.)

Technology has certainly been another significant domain where power is executed and can be repurposed. I completely agree that it’s one of the big problems of our age that technological development is mostly in the hands of corporations. But, as your example of the techies demonstrates, there exists a considerable group working at pivotal places in the tech business that identifies with the history of nerd culture and its anarchic conduct. To them, the internet is a public space in the utopian sense of not being controlled or monitored. What they see and want to change, however, is a dystopian space controlled by capitalist interest groups and authoritarian government branches.

Andrew:

This has been a wonderful conversation. I appreciate your invoking of De Certeau… and Obama is an apt model for techies! Those who were young adults in the late 2000’s were mobilized by the messages of hope in his first campaign and helped get the vote out for him. Obama also was bullish about trying to institutionalize technology design at the federal level through the US Digital Service, appointing CTOs, and so on. He forever will inform the way they think about moderate democratic politics. The question I return to is if techies’ infrastructural politics can change larger political and technical systems (that often move at a glacial pace, or are yoked to capitalist impulses)? Or if they are ways to – like De Certeau’s vison of tactics as taking shortcuts through the city – carve new routes and spaces that form sites of organizing outside of institutions. I admit, this discussion of institutional reform opens up far more questions, some of which lie outside of mediated politics, than it provides easy answers.

We’ve also managed to put into fruitful conversation two traditions in communication that are often kept distinct: media and technology. Many techies struggle with gaining widespread recognition for their predominantly administrative work. They try to employ memes and imagine themselves as a social movement proper. But, simply put, often their work is quite boring. (who Who really gets excited about fixing the department of motor vehicles (DMV)?) As a result, non-profit tech design organizations that are good at media, like Code for America, use social justice storytelling and patriotic imagery to make powerful arguments about the “public good.” This is what lets them tap into multiple funding streams from private tech companies and non-profit foundations. Clearly, one lesson is that we need to keep both media and technology traditions in the room to understand political organizing.

I feel like I have taken up space benefitting from applying your concepts about media activism and culture jamming to techies, while not asking enough questions that might help us think about the inverse question: how has technology changed the work of media activists and culture jammers? While not all media-oriented activists and culture jammers use social media platforms, it is clear in an age of unbridled populism and white nationalism that these are often the conduits for radicalization and resistance. Do they see hacking and reconfiguring digital platforms as a form of “billboard banditry,” as you put it, to reach a mass audience? Has this changed in the last ten years? Where are the valuable opportunities for this political work?

Mo:

Great to hear that our take on culture jamming adds to your research, Andrew. Certainly, the new media environment of “social” media (or whatever we want to call communication platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) has shaped media culture to great degrees, and thus provided new instruments for media activists and culture jammers. While “hackers” have comprised a subculture of technology geeks, which has partly informed the concept of culture jamming as laid out by cultural critic Mark Dery, I don’t see hacking per se as culture jamming. Creative as the sabotage of digital infrastructures may be, it doesn’t necessarily share culture jamming’s impulse of raising public awareness, of sparking up the civic consciousness, of “exposing institutional or corporate wrongdoing,” as Dery put it in his 1993 manifesto, Culture Jamming, which is also reprinted in our collection.

But, sure, the digital world constitutes a public space for our networked society that invites for media activism and acts of culture jamming. An early example here is the Yes Men’s launch of a faux WTO website, www.gatt.org, in the year of 2000 (which is no longer active but still accessible through the Internet Archive). Notably, the two activists didn’t hack the WTO’s internet presence, but rather used the web’s surface to adopt the organization’s identity. Surprisingly, perhaps, many fell for the Yes Men’s coup, believing the website was authentic. As a consequence, the Yes Men were officially invited as WTO representatives to conferences and other public events, which enabled the duo to proceed with their hoax, and to circulate subversive messages in the name of the WTO.

On the other hand, I’m afraid that the mediasphere is much more complex today than in earlier days. Digital platforms may offer new venues for activists, but echo chambers and filter bubbles make it increasingly difficult to reach people’s attention and promote social change. Also, creative forms of protest – what we defined as culture jamming – has long since ceased to be solely a phenomenon associated with a liberal or leftist political position.

I’m shocked again and again that the meaning of what we call the “public good” seems to be as disputed as ever: The visual culture around Obama that we saw during his landmark electoral campaign also influenced Trump’s campaign. Thanks to its power as forms of guerilla communication, which aims to go “viral,” culture jamming has been coopted not only by the ad industry but also by political movements – both on the left and on the right. Occupy Wall Street and its artistic sensibility is still fresh in our minds, but neo-Nazi groups and right-wing populists such as the AfD, Germany’s far right party mentioned earlier, have also tapped into brandjacking, the civic imagination, and internet memes to popularize their campaigns.

So, I think you’re absolutely right. Intervention and reconfiguration within the technology sector – e.g., by techies acting as media activists – is an important way to reclaim not just the datasphere itself as a democratic space, but also the civic imagination as a form of democratic expression rather than of vulgar populism and hate speech.

————

Andrew Schrock earned his Ph.D from the Anneberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. He is currently a researcher at Chapan University and an instructor at UCLA and USC. His research considers how grassroots groups and governments can ethically use technology to improve life for residents. He is particularly interested in taking an organizational perspective on public sector technology design, and how organizing can lead to institutional change. Andrew’s research has appeared in New Media & Society; The International Journal of Communication; and Big Data & Society. For more on Andrew’s work and teaching, please visit his website at aschrock.com.

Moritz Fink is an independent media scholar based in the Munich area, Germany. He has published on contemporary media culture and popular satire. Mo’s latest book, a cultural history of the veteran TV show The Simpsons, will be released by Rowman & Littlefield in June. He contributed to this blog in the past with posts about remix culture and media pranks, and is the coeditor of Culture Jamming: Activism and the Art of Cultural Resistance (NYU Press, 2017