Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Winifred R. Poster & Gabriel Peter-Lazaro (Part II)

/Winnie

I’m so thrilled to learn about the civic imagination project! This is such an important foundation for social change. People need to have a vision of an alternative, as well as a confidence that another society is possible, before they can act towards it. I’ve encountered this in my activism, when I meet people who are so disillusioned by the current situation that they feel there is no way out. When we go out canvassing and ask “what issues do you care about most?” they don’t even want to talk about it. They just shut down. A major question among my action group is how to talk to young adults especially, and convey a sense of hope. Seems like there is one segment in this generation which is super-energized, and in so many ways, pushing the agenda of change much more radically than my gen-x cohort. But in parallel, another segment is mentally drained by the compounding inequalities of class, race, sexuality, gender, citizenship, physical ability, etc., that our national leaders have failed to address.

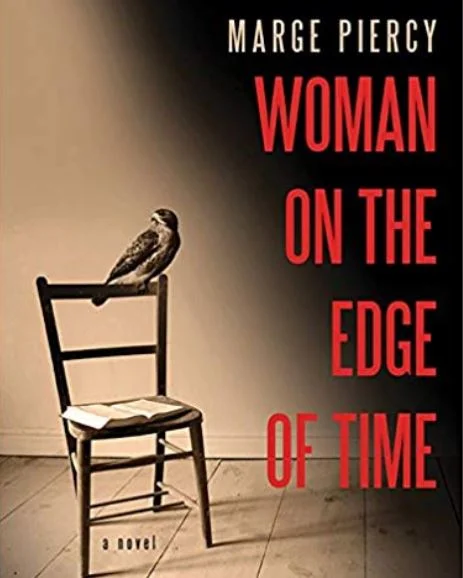

It’s also been a part of my scholarly trajectory, and what drew me to sociology as a discipline. I loved the big questions that “grand theory” was asking, in terms of why societies are organized the way they are (especially in their political economies), and what would it take to move to an alternative organization. In my teaching, I assign books like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, so that students can see an example of a feminist utopia, and then craft their own through critique and comparison to their own ideals. In my global human rights course, I spend the first day showing them what the United Nations defines as human rights, and then deconstructing it – contrasting it to models by legal scholar Martha Nussbaum and environmental activist Vandana Shiva, and significantly, to what they think it should be. But these are very structured exercises, and it sounds like what you are doing in your workshops is much more organic, free-flowing and open-ended.

Gabe

It’s extremely helpful and gratifying to hear your enthusiastic impressions of the civic imagination work. Your perspective about ‘issue fatigue’ is especially resonate and something we’ve encountered in our work from the beginning. In our very first iterations of the creative workshop approach - even before we had honed in on the civic imagination nomenclature - we felt that we had to justify the creative work by framing it in political or activist terms. We thought that we would have to put issues first, and then make baby steps towards the world building work and visioning activities. One of our first community partners though shared a perspective at the outset that became core to our whole approach. Susu Attar - an LA-based artist and activist - was helping to run a summer youth leadership academy at the Islamic Center of Southern California where we were slated to run a weeklong workshop. Her feedback on our workshop plans was that the youth participants spent their whole lives with their identities already politicized, and what they needed most was a break from that where creativity could come first. We took the note and put imagination first. What we discovered was that the issues, values and real world challenges faced by those participants in their communities emerged organically through the activities of future visioning and narrative building. This led to sustained dialog about complicated issues, but having arrived at that point through the lens of fantasy and imagination brought a new kind of energy and understanding to the problems that might have been elusive if they had simply been dredged up head-on.

Over the next several years as we developed these workshops and brought them to diverse communities, we encountered consistently similar results. We sometimes experienced skepticism and resistance from groups that we worked with, but in each case, those feelings melted away and we received feedback that the civic imagination framework was meaningful, productive and a great way to see the world in new ways and potentially build empathy and bridges across previous divisions. All that being said, I think that our team still struggles with questions about how these positive aspects feedback into more action-oriented outcomes and activities. How could groups, communities or institutions practice civic imagination together and then harness that creative practice in an ongoing, sustainable way? In what contexts or communities would that be feasible and make sense? One of the ideas we have been playing with for a while but have yet to implement effectively, is to create a mechanism of collaboration and interaction between groups and across geographic distances, whereby folks running a civic imagination in one place could produce an outcome that includes a creative challenge or inspirational jumping off point to be taken up, explored and built upon by another group somewhere else. The idea would be to support emergent network structures between groups and individuals who are looking for new kinds of imaginative civic structures and visions that might lead to productive alliances and actions in the future. This is the point where the question of technology comes back, as we imagine that the mechanisms for these interactions would be mediated through online tools.

Winnie:

Yes, I was struck by the similarity of experiences we’ve had, in terms of with ambivalences of technology. Your students are expressing the same tensions that I feel in using these devices as tool of activism. On one hand, it seems like your students have a remarkable self-awareness. I’m impressed how they recognize the lack of choice in technologies they use, and the totality that it can encompass in their lives.

On other hand, I’m also glad you mentioned the problem of technology giving people a false sense of taking action. It reminds me of what some call “clicktivism,” and the assumption that pressing a few buttons, to sign a petition or email a political message, will create substantive change in itself. Such transformation takes effort both off and online, as well as endurance and persistence. (Just in the past year, I’ve seen how our herculean efforts to achieve progressive policies through popular vote in Missouri – anti-gerrymandering initiatives, minimum wage increases, etc. – are now being derailed in the state legislature. Activism is continuing process.)

Gabe

I was really intrigued by all the examples you gave in your opening statement about the tools that have become so widespread and useful across various examples of organizing and activism. There is such a spectrum from the mundane to the profound in terms of how these networked actions facilitate both novel and familiar forms of collective action. It sets me to musing about what tech might be useful for this civic imagination work. Our approach so far has been decidedly low-tech; it’s very much based on face-to-face interactions, writing notes on whiteboards, building low-res constructions out of paper and glue, getting up on our feet and performing for the people in the room. Yet the other hat I wear as an instructor and practitioner in a school of cinematic arts, I am deeply interested in all kinds of emerging media technologies and the impacts they have on the ways that we represent and ultimately conceive of our realities. I explore things like giant screen cinema, virtual reality and aerial photography with my students at USC. As with all tech innovations there seem to be both emancipatory and cautionary aspects to each new wave of development; opportunities for new voices and visions to emerge, or else for the same structures of power and influence to reaffirm exclusionary boundaries. I think what I’m trying to get at is that I see a need for civic imagination to get a handle on tech, and for tech to get a dose of civic imagination.

Many of the future-world stories that come out of our workshops include ambivalent visions of a kind of techno-authoritarian-corporatism; governments have faded away and power is wielded by corporate monoliths who deliver amazing technologies but with the price control and domination. We certainly see the value of this ‘dark side’ of the civic imagination; lots of the stories that come up aren’t utopian at all, but rather are ways of working through anxieties and fears with a fanciful spin and narrative distance. And maybe these sorts of stories help galvanize our recognition of current authoritarian threats and create new spaces for exploring those feelings of dread so that they might be channeled into grand acts of imaginative resistance.

__________

Winifred R. Poster teaches in International Affairs at Washington University, St. Louis. Her interests are in digital globalization, feminist labor theory, and technologies of activism. With a regional focus on South Asia, she follows the outsourcing of high tech and call center labor. Her research explores ethnographic transformations in service work through automation, artificial intelligence, crowdsourcing, and virtual assistants. She also has projects on surveillance, national borders, and cybersecurity. She is a co-author of Invisible Labor (UC Press) and Borders in Service (University of Toronto Press). She has contributions in forthcoming books Captivating Technology (Duke University Press) and DigitalSTS (Princeton University Press).

Gabriel Peters-Lazaro, M.F.A., Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts where he researches, designs and produces digital media for innovative learning. His current research interests include Civic Imagination and Hypercinemas and he is a practicing documentary filmmaker. His courses deal with critical media making and theory.