Spreadable Media: Creating Meaning and Value in a Networked Culture, my new book with Sam Ford and Joshua Green, is launching at the end of January. Each week, we are releasing new essays written by friends and affiliates of the Futures of Entertainment Consortium which expand upon core ideas in the book. You will see that these essays are an integral part of the book, even though they are being distributed digitally. We also see these essays as a means of sparking key conversations in anticipation of the book's release. So, in the spirit of this project, "if it doesn't spread, it's dead," so we are asking readers to help circulate these essays far and wide to as many different networks and communities as they seem relevant to the ongoing conversation.

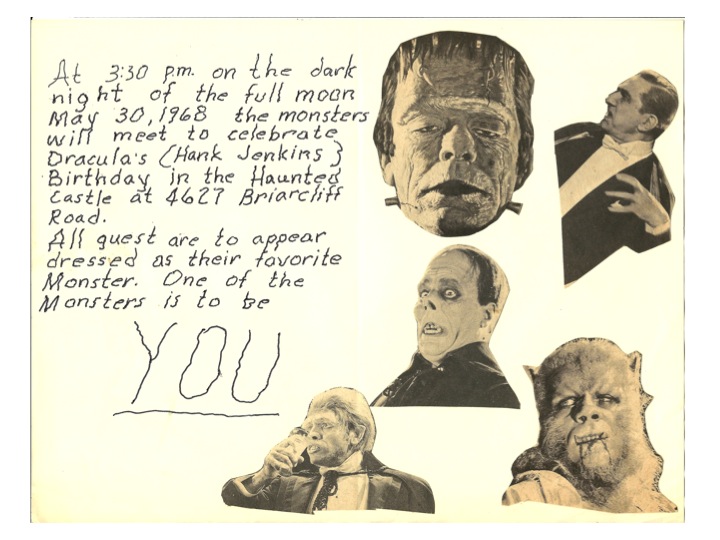

Readers are already responding, including through the creation of "memes." Over the weekend, we received this "Slap Robin" announcement via Twitter from @amclay09.

Share with us your own creations and I will showcase this here as I am posting upcoming essays.

This week, we are releasing essays which are tied to the Introduction and first Chapter of the book.

Before I do so, let me share some of the early responses to the book (i.e. the solicited blurbs):

“Something new is emerging from the collision of traditionIal entertainment media, Internet-empowered fan cultures, and the norms of sharing that are encouraged and amplified by social media. Spreadable Media is a compelling guide, both entertaining and rigorous, to the new norms, cultures, enterprises, and social phenomena that networked culture is making possible. Read it to understand what your kids are doing, where Hollywood is going, and how online social networks spread cultural productions as a new form of sociality.”—Howard Rheingold, author of Net Smart

“By critically interrogating the ways in which media artifacts circulate, Spreadable Media challenges the popular notion that digital content magically goes ‘viral.’ This book brilliantly describes the dynamics that underpin people’s engagement with social media in ways that are both theoretically rich and publicly meaningful.”—danah boyd, Microsoft Research

“The best analysis to date of the radically new nature of digital social media as a communication channel. Its insights, based on a deep knowledge of the technology and culture embedded in the digital networks of communication, will reshape our understanding of cultural change for years to come.”

—Manuel Castells, Wallis Annenberg Chair of Communication Technology and Society, University of Southern California

“Finally, a way of framing modern media creation and consumption that actually reflects reality and allows us to talk about it in a way that makes sense. It’s a spreadable world and we are ALL part of it. Useful for anyone who makes media, analyzes it, consumes it, markets it or breathes.”—Jane Espenson, writer-producer of Battlestar Galactica, Once Upon a Time, and Husbands

“It’s about time a group of thinkers put the marketing evangelists of the day out to pasture with a thorough look at what makes content move from consumer to consumer, marketer to consumer and consumer to marketer. Instead of latching on to the notion that you can create viral content, Jenkins, Ford, and Green question the assumptions, test theories and call us all to task. Spreadable Media pushes our thinking. As a result, we’ll become smarter marketers. Why wouldn’t you read this book?”—Jason Falls, CEO of Social Media Explorer and co-author of No Bullshit Social Media

This week's selections include discussions of historical predecessors, Memes and 4Chan, the debates about free labor, co-creation in the games culture, and the power of consumer recommendations. Read the sample. Follow the links (....) back to the main site. Read. Enjoy. Spread. Repeat next week.

The History of Spreadable Media

Media have been evolving and spreading for as long as our species has been around to develop and transport them. If we understand media broadly enough to include the platforms and protocols—to use Lisa Gitelman’s (2006) terms—that carry our stories, bear our messages, and give tangible expression to our feelings, they seem intrinsic to the human experience. Some people might even argue that the developments of vocal communication systems (language) and visualization strategies (paintings and carvings) represent defining moments in human evolution, demonstrations of man’s social nature. Human mastery of media was every bit as important as the mastery of tools. Stories of the spread and appropriation of media run across our history, each shaped by the logics of social organization and production characteristic of any given era.

Early traces of the spread and reach of media abound, even if some historical forms of media fall outside our familiar categories. For example, our contemporary understanding of the reach and influence exercised by ancient empires owes much to discoveries of coins—a medium of abstract exchange if we follow Karl Marx’s argument in Capital ([1867] 1999) and elsewhere but also a system of representation and meaning (from the value of the gold or silver to the inscribed monetary value, to the messages or portraits etched on its surface) with precise culturally defined borders. The coin, as a medium, spread with the state’s citizens, enabling their interactions with one another and at the same time attesting to the state’s reign. Ceramic dishes and tiles offer an example of a medium that was seized on for reasons of cultural exchange. The rich intermingling of styles and techniques characteristic of early-seventeenth-century Dutch, Chinese, and Ottoman ceramics speaks to the period’s trade routes and export markets and the creative appropriations of these various cultural models by its artisans. But these ceramics were also platforms, complete with highly nuanced systems of signification, hierarchies of value, and attendant associations of taste. They were carried, traded, collected, and displayed by a surprisingly large cross-section of the northern European population. As the ceramics circulated within different social groups as the vogue for ceramics rose and fell and were handed down to our present as family heirloom or antique shop curio, the journeys they undertook, and the meanings accorded them as media, attest to the energies and interests of those who helped to spread them....

In Defense of Memes

Although I agree that the terms “viral” and “meme” often connote passive transmission by mindless consumers, I take issue with the claim that “meme” always precludes active engagement—or that the term has a universal, static meaning. As understood by trolls, memes are not passive and do not follow the model of biological infection. Instead, trolls see (though perhaps “experience” is more accurate) memes as microcosmic nests of evolving content. Contrary to the assumption that memes hop arbitrarily from self-contained monad to self-contained monad, memes as they operate within trolldom exist in synecdochical relationship to the culture in which they inhere. In other words, memes spread—that is, they are actively engaged and/or remixed into existence—because something about a given image or phrase or video or whatever lines up with an already-established set of linguistic and cultural norms. In recognizing this connection, a troll is able to assert his or her cultural literacy and to bolster the scaffolding on which trolling as a whole is based, framing every act of reception as an act of cultural production. Consider the following example.

Founded in the early nineties by rappers Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope, the Insane Clown Posse (ICP) is a Detroit-based hip-hop group infamous for its violent lyrics, rabid followers, and, as it was recently revealed, secret evangelical Christianity. ICP, which performs in full-face clown makeup, has always been a target for trolling humor. The 2010 release of the group’s single “Miracles,” however, opened the floodgates—in the video, Violent J and Shaggy earnestly extol the virtues of giraffes, rainbows, cats, and dogs, not to mention music (“you can’t even hold it!”) and the miracles of childbirth and the cosmos. The song itself, which is regarded as the group’s evangelical “outing,” is peppered with expletives and features the line “Fuckin’ magnets—how do they work?” a question which inspired immediate and seemingly endless repurposing.

Within a few days of the video’s release, dozens of remixed images and .gifs were posted to 4chan’s infamous /b/ board, many of which merged with existing memetic content. A well-known image of a cross-eyed, bespectacled man captioned with the phrase “are you a wizard,” for example, inspired a series of related macros, including one featuring a close-up shot of Violent J in full makeup. “are you a magnet,” the caption reads, referring not just to the cluster of memes related to the “Miracles” video but also to all the permutations of the “are you a wizard” family of macros.

In short, trolls pounced on the phrase “fuckin’ magnets” not just because it was memorable and amusing on its own (although that played a large part in its popularity, as did the thrill of a gratuitous f-bomb) but because it was easily integrated into an existing meme set. Once the protomeme had been integrated, its resulting permutations—“are you a magnet” being a prime example—became memes unto themselves, establishing further scaffolding onto which new content could be overlaid. By choosing to repost “are you a magnet” on 4chan or off-site, the contributing troll was able to assert his own cultural fluency and, in the process, ensure the proverbial (and, in some ways, the literal) survival of his species. In this sense, the creation and transmission of memes can be likened to the process of human reproduction—specifically the decision to have a child in order to protect one’s legacy. The sexual act is decidedly active, but the resulting zygote is a passive (that is to say, unwitting) vessel for genetic information....

Interrogating “Free” Fan Labor

Over the past two decades, large swaths of the U.S. population have been engaged in copyright wars. On one side, copyright holders struggle to defend their property against what they perceive to be unlawful appropriation by millions of would-be consumers via digital technologies. On the other, millions of Internet users fear or fight expensive lawsuits, filed by entities far wealthier and more powerful than they, that seek to punish them for sharing media online. In this combative climate, fans who produce their own versions of mass-media texts—fan films and videos, fan fiction, fan art and icons, music remixes and mash-ups, and game mods, for example—take comfort and refuge in one rule of thumb: as long as they do not sell their works, they will be safe from legal persecution. Conventional wisdom holds that companies and individuals that own the copyrights to mass-media texts will not sue fan producers, as long as the fans do not make money from their works (for instance, Scalzi 2007 and Taylor 2007).

“Free” fan labor (fan works distributed for no payment) means “free” fan labor (fans may revise, rework, remake, and otherwise remix mass-culture texts without dreading legal action or other interference from copyright holders). Many, perhaps even most, fans who engage in this type of production look upon this deal very favorably. After all, movie studios, game makers, and record labels do not have to turn a blind eye to fan works; U.S. law is (as of this writing) undecided on the matter of whether appropriative art constitutes fair use or copyright infringement, so companies could sue or otherwise harass fan appropriators if they chose. But, even if both sides of the copyright wars consider the issue of fan labor settled, one aspect of the issue has not been sufficiently explored: can, or should, fan labor be paid labor?....

Co-creative Expertise in Gaming Cultures

Gamers increasingly participate in the process of making and circulating game content. Games such as Maxis’s The Sims franchise, for example, are routinely cited as exemplary sites of user-created content. Games scholar T. L. Taylor comments that players are co-creative “productive agents” and asserts that we need “more progressive models” for understanding and integrating players’ creative contribution to the making of these game products and cultures (2006b, 159–160; see also 2006a). Significant economic and cultural value is generated through these spreadable media activities. The usual phrases such as “user-created content” and “user-led innovation” can overlook the professional work of designers, programmers, and graphic artists as they make the tools, platforms, and interfaces that gamers use for creating and sharing content. Attention should also be paid to the work of producers, marketing managers, and community relations managers as they grapple with how best to manage and coordinate these co-creative relations.

The Maxis-developed and Electronic Arts–published Spore thrives on user-created content. Players use 3-D editors to design creatures and other in-game content, to guide their creatures through stages of evolution, and then to share their creations with other players. Since Spore’s release in September 2008, more than 155 million player-created creatures have been uploaded to the online Sporepedia repository. Players can also upload directly from within their game videos of their creatures to the Spore YouTube channel. Spreading content is a core feature of Spore; the game is perhaps best understood as a social network generated from player creativity. This spreadability is not just about content, as the players are also sharing ideas, skills, and media literacies....

The Value of Customer Recommendations

With new channels of communication and old, marketers can deliver a dizzying number of advertising messages to consumers—by many accounts, the average American sees between 3,000 and 5,000 ads a day. Yet, perhaps in response to this fusillade, consumers have learned to better armor themselves against the marketing messages they encounter. The Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) describes the extent to which consumers develop a radarlike ability to discern content whose aim is to persuade and, further, how they develop a set of skills to deal with such messages (Friestad and Wright 1994). Some of my own recent research (with colleagues Adam Craig, Yuliya Komarova, and Jennifer Vendemia) uses fMRI technology to explore brain activity as consumers are exposed to potentially deceptive product claims. Our findings show that consumers’ deception-detection processes involve surprisingly rapid attention allocation. Potential advertising lies seem to jump out of the marketing environment and rivet our attention like a snake on a woodland trail.

Advertisements are often informative as well as persuasive; consumers know this and don’t dismiss ads out of hand. But they do assess the extent to which they trust or are willing to use such information. First, and most critically, consumers seek to evaluate the credibility of a marketing message’s source. Source credibility is the bedrock of trust that precedes persuasion. People judge a source to be credible if the source shows evidence of being authentic, reliable, and believable. In the old days of marketing, firms sought to increase the source credibility of their ads by featuring the endorsements of doctors, scientists, and other authoritative experts. Once consumers became more aware that these experts were being paid handsomely for their testimony, the practice became less effective. Celebrity endorsers, who often were not product experts, provided warm affective responses but little in the way of believable, persuasive arguments.

Consumers themselves are particularly important endorsers via word-of-mouth (WOM) messages. Our past understanding of WOM (when one consumer recommends a product to another) was that consumers perceive other consumers as highly authentic but of dubious reliability. As when one’s Uncle Joe touts the superior performance of the Brand X computer, the recommender is clearly a real person but may or may not be knowledgeable enough about the product category to make credible claims. Now, with WOM increasingly occurring through spreadable media, it is more difficult for a consumer to assess both the authenticity and reliability of unknown recommenders. The practice of rating consumers’ online opinions and recommendations (e.g., Yahoo! Answers) is a direct attempt to resolve the audience’s uncertainty about who really knows something worth knowing....