The Queen’s Gambit Is Not a Total Win for Women

/This week, my blog is going to catch up on some buzz-worthy television series. Today, we have a stand-alone piece which offers a feminist critique of The Queen’s Gambit and later in the week, I am sharing a conversation about race and representation in Lovecraft Country. Both of these are series well worth watching and debating. These pieces will contain “spoilers” so read at your own risk. But I know many of you will have already binge watched these two series.

Joss Areté Kelvin — among other things, my former assistant — shared this piece with me just before the holidays as something that she felt compelled to write and I asked if I could share it to my blog readers. Kelvin contributed to our 2020 book, Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination: Case Studies of Creative Social Change, and has stayed in touch as she has been completing a degree in creartive writing at the University of Manchester. Her piece on pop divas and their response to Trump proved particularly prescient since three of the divas she discussed — Lady Gaga, J-Lo, and Katie Perry — performed at the recent inauguration. (What happened to Beyounce, I want to know). This piece led me down the rabbit hole of binge watching this series. Who knew chess competitions could generate such compelling television? Enjoy!

The Queen’s Gambit Is Not a Total Win For Women

By Joss Areté Kelvin

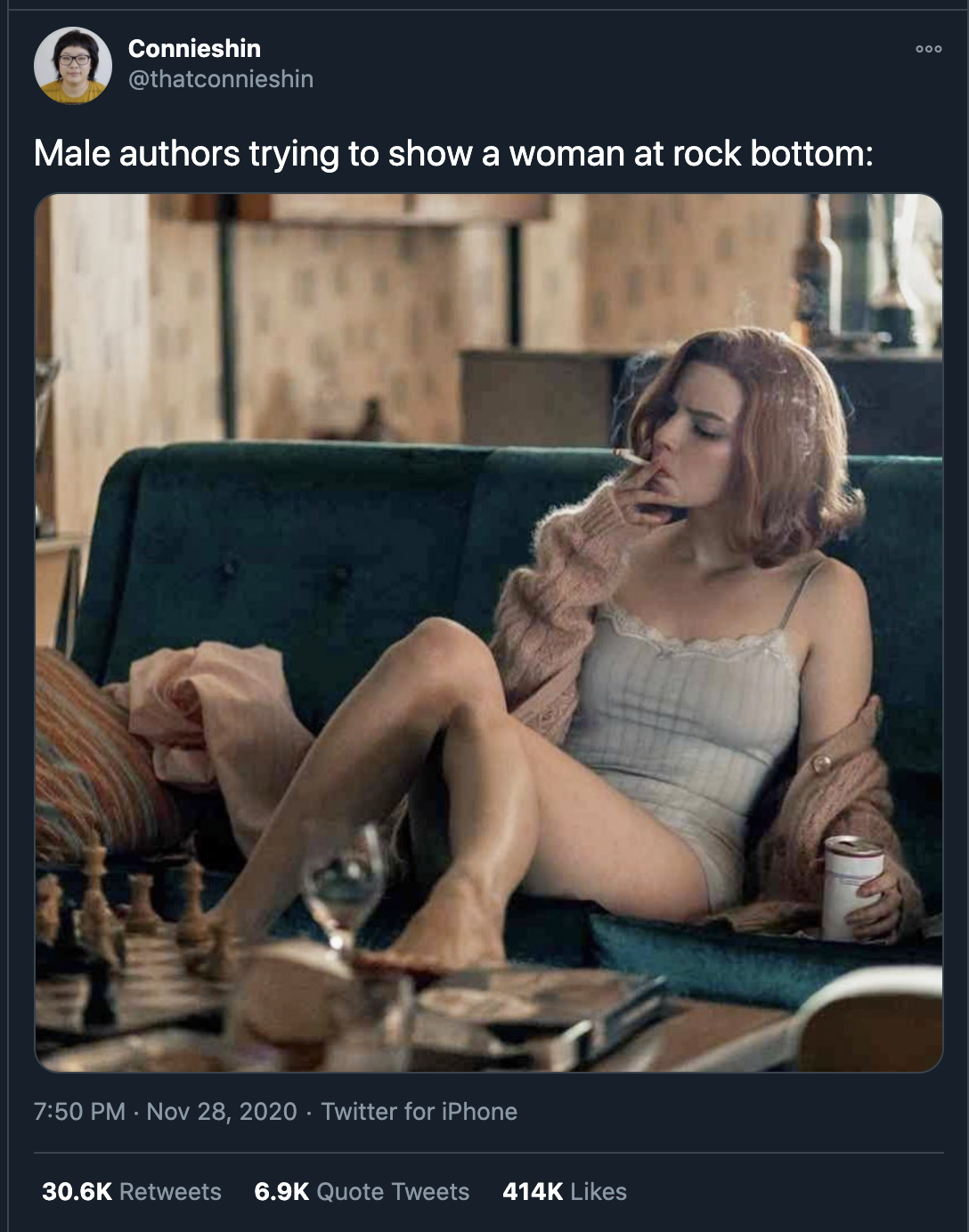

Everyone has been telling you the truth: The Queen’s Gambit is a fabulous time. As you’ve likely heard by now, the show is brilliantly acted, gorgeously shot binge-worthy television. The writing is fluid, the production and costume design impeccable, and the chess depicted in a way that is accessible, suspenseful, and cinematic. And every intelligent woman I know who has watched the show has had a variation on the same response: what a thrill, to watch a smart, ruthless, messy, extravagant woman take on the world—and win. The show is a pleasure. But at risk of holding an unpopular opinion: it isn’t an unadulterated one.

The Queen’s Gambit may feel empowering, and in certain ways it is. But the show tells the same, old, cis-male story of exceptionalism that Hollywood has been stuffing down our throats for years. Here it feels empowering; but only because that story has so rarely been told via the body of a woman.

Exceptionalism: the idea that if you are important enough, you can act however you like, and the other people in your life will always be there to support you—no matter how much you abuse them. Exceptionalism means that, because you are in some way perceivable as superior, you do not have to be quite as human. Think Mad Men’s Don Draper, or House’s Dr. Gregory House. Like both of these quintessentially exceptionalist male characters, Beth Harmon is a high-achieving, lonely alcoholic/addict, generally called by her last name. As in the lives of Draper and House, everyone in Harmon’s world orbits around her, showing up when she needs them and sacrificing elements of their own lives to make hers functional. Like Draper and House, in the face of all of this support, she puts her work above her humanity in a way that both protects and isolates her. And while people get angry at times, in the end they are always awed. (Another great example of this type is Sherlock—though he’s called by his given name.) As for the audience, we’re so used to perceiving Harmon’s obsessiveness and self-absorption as the price of success on male bodies that it feels powerful writ on a woman’s. But, in fact, it is still limiting.

In the world of The Queen’s Gambit, Beth Harmon is not a woman, and therefore equal. She is a chess prodigy, able to beat twelve teenage boys at the same time—as an eleven year old girl. Beth Harmon “deserves” her dominance, the pedestal that all the men in her life put her on. Unlike the rest of the women in the world, who have to toe the line, compromise their needs, and conform to a patriarchal society in which men dominate, Harmon can be rude, condescending, and selfish, and the men in her life will always return to support her. Because she’s a Cumberbatch, aka an antisocial genius, and that is the height of male-penned superiority.

There’s a bit of a wrinkle to this Cumberbatchian isolated genius role, though: Harmon isn’t isolated. In the end, the show emphasizes collaboration, and Harmon’s acceptance of help defines her arc. She witnesses how the Soviets work together in order to carry their players to success, and is enabled, via last minute intervention from her American community, to walk into her final championship game fully prepared—though the winning choices are hers, and hers alone.

I would argue this journey is mirrored in other fiction following this pattern—for example, Mad Men’s arc aimed to reveal the fallacy of Draper’s self-islanding—but here, the teamwork message could not be more explicit. This adds an interesting aspect to the gender politics of this story, in that it can be read as an empowering choice, disrupting the auteur myth, or, given that Harmon’s group of chess helpers are entirely male, as implying that women need men’s help to succeed. In this case, my interpretation falls towards the first camp. I see this collaboration aspect of the narrative as a positive. But I also believe that placing such a high emphasis on collaboration isn’t divorced from the lead character’s gender.

It’s exciting to see a female Cumberbatch role, I’m not going to lie. It’s exciting to see a female character be exceptional for her brain, rather than her body. But it’s the same one-woman-in-a-world-of-men story we’ve been telling for decades, and whether it’s twenty-five years ago and Angelina Jolie is playing a badass computer geek in Hackers or a car thief Gone in Sixty Seconds, or it is 2020 and Anya Taylor-Joy is playing a chess prodigy—it’s a dangerous message. It’s a message that tells women: if you aren’t both intellectually dominant and outrageously sexually attractive—you’re not in the story at all.

Which isn’t to say that there aren’t other great women in this story. One of the reasons that The Queen’s Gambit remains a pleasure, even with everything I’m calling out here, is that there are other strong female characters, most notably Harmon’s adopted mother (Marielle Heller) and her best friend from the orphanage, Jolene (Moses Ingram, my vote for breakout star of this show). The relationship between Harmon and her mother is, in my opinion, the strongest and most complex part of the show. It reveals both mother and daughter as multi-faceted, emotionally vulnerable and yet quintessentially strong women.

Harmon’s relationship with French model Cleo also has a great dynamic—though the decision to avoid depicting any actual expression of the sexual chemistry between the two feels like a frustratingly lost opportunity. But the relationship between Harmon and orphanage-sister Jolene is the most abrasive mistake that the show’s creators have made.

Jolene is a deeply likeable character; actually, she’s too likeable. She’s a textbook example of the Magical Negro, an even more destructive incarnation of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl or Magical Queer. These tropes sweep in and save the central character from their own self-destruction, but have no arc themselves. They exist in subservience to the growth of the main character. As I’ve mentioned, everyone in this show does—but what makes this particularly destructive, when writ on Black bodies, is that it becomes part of a larger silencing. A savior character in a Black, female, queer, or other minority body messages that people in these bodies exist in subservience to white, cis protagonist exceptionalism.

The writers of Queen’s Gambit knew enough to address this—they wrote Jolene to actually say ‘I’m not here to save you. Hell, I can barely even save me,’—but it feels like lip service to a criticism they knew they might receive. In fact, the character does show up explicitly to save Harmon, which is not true in the source material—in the novel, Harmon reaches out to Jolene and asks for help. So, this shift was chosen by the show’s creators. Of all the characters in the show who only exist to support Harmon’s arc, this is the most egregious mistake.

Why have these mistakes in representation been made in an otherwise deeply considered piece? If you look into the power structure of the creative team The Queen’s Gambit, you’ll find only men. A man wrote the novel; men adapted that into a screenplay; a man directed it; and men produced it, scored it, and worked as the cinematographer. The highest-level female positions on this production were star, editor, casting director, and art direction-related positions. All of which is to say: there were no women in the central rooms of development outside of a stray female executive here and there.

To that end, I would like to say kudos and thank you to all of these men for using your power to make a piece of art that centered on a complex, intelligent woman. But I would also like to say: your decision to not include a woman in the top circle of power? It shows.

I am not saying that every good show has to accomplish everything. Every woman I know has fallen in love with this show, myself included—I watched it twice! But for all of the kudos that The Queen’s Gambit is rightfully receiving, it’s still not quite as much of a step towards empowerment as it appears to be. While you may have written it on a differently shaped body, the messages are not new, and they reinforce ideas that can still be harmful to developing women. The Queen’s Gambit suggests that if you’re a woman, you can play at an advantage—but only if you sacrifice your humanity and beat all the goddamn odds to become the absolute best. That is the only way you can win.

Can we tell an equally addictive, thrilling story without requiring our female characters to be dominant in the same distant, carnivorous way as our male characters? Can we not only tell female stories—but allow women to tell them? Hey, Hollywood, what do you say? The record-breaking 62-million person audience of The Queen’s Gambit in all 92 countries in which it was on Netflix’s top ten in its first month since release—would love to know.

Joss Areté Kelvin is a non-binary/female writer and multimedia artist. They directed and produced Your Friends Close, a festival premiering feature film, currently streaming on Amazon; released music and video art, headlined LA venues and played festivals as Areté; devised, produced, and performed in immersive nightlife and music events, and are currently developing interactive web, mobile, and VR experiences. Their non-fiction writing has been published in Popular Culture and the Civic Imagination (2020) and online at The Manchester Review. They served as event producer for the Transforming Hollywood conference (USC/UCLA), and produced other future-focused symposiums & workshops during their time working for Henry Jenkins—and, coincidentally, also designed this site! Born and raised in New York City, they graduated magna cum laude from Northwestern University in Chicago, and lived in Los Angeles before expatting to the UK, where they just completed their MA (Distinction) in Creative Writing from the University of Manchester, as well as serving as Editor of the annual Anthology. You can follow their Medium here.