Comics & Stuff: The Interviews (3 of 4)

/Michael Saler

The relations among history, memory and nostalgia are major concerns in comics by Art Spiegelman, Joe Sacco, Marjane Satrapi, Jason Lutes and many others. Your own explorations of graphic novels tends to highlight their fluid, multidimensional and open-ended nature, but do you find that contemporary narratives continue to risk forms of reification and closure despite their metafictionality? I’m thinking about Seth, who in effect has reified himself as a person, perhaps inadvertently – can Seth ever take off his hat and tie? Has he, like the characters he represents, become a captive of his his possessions and nostalgic yearnings?

Henry Jenkins

Each of the authors you identify here raise their own questions -- several of them are folks I considered writing about in this book, but let me bracket them and focus on Seth, who I do write about.

You are absolutely right that in some ways, Seth has turned himself -- his living persona -- into a caricature who seems to have stepped directly off the pages of his graphic novels. He talks about his persona, his lifestyle as being one of his creative projects. He represents a kind of dandy-ish self-fashioning which serves to situate him in the mid-century world that his characters want to get back to. And this certainly makes it easy to recognize Seth’s self-representation in his graphic novels, whether he acknowledges the connection or not. He constructs himself there as a sensitive soul for whom nostalgia borders on mental illness.

You are absolutely right that in some ways, Seth has turned himself -- his living persona -- into a caricature who seems to have stepped directly off the pages of his graphic novels. He talks about his persona, his lifestyle as being one of his creative projects. He represents a kind of dandy-ish self-fashioning which serves to situate him in the mid-century world that his characters want to get back to. And this certainly makes it easy to recognize Seth’s self-representation in his graphic novels, whether he acknowledges the connection or not. He constructs himself there as a sensitive soul for whom nostalgia borders on mental illness.

As I suggested in my analysis, some of these representations of fans and collectors would offend me in other contexts. Yet, there is a sense that Seth owns these stereotypes. They are representations of self and not others. They are understood from the inside and not the outside. They are sometimes self-parody and sometimes self-pity. If the character seems overwhelmed, the artist is still showing his mastery in finding a way to express these relationships through his work. I am really fascinated by the ambivalence he shows towards his own community and by the ambivalence he arouses in me as I look at these otherwise stereotypical constructions. Is he possessed by his possessions? Almost certainly, but part of what makes the meta-text dizzying, is that he knows—and expects us to know—that he is possessed by his possessions.

William Proctor

I am a massive fan of Bryan Talbot’s work, ever since I was first introduced to his work in ‘Nemesis the Warlock’ in the British weekly science fiction comic 2000AD (which remains one of the last survivors of the UK comics collapse of the late-1980s and early-90s). Nevertheless, I was stunned when you informed me that you’d be exploring Talbot’s magnificent Alice in Sunderlandfor Comics and Stuff back in 2013 when we first met, principally because I was born-and-bred in Sunderland, and couldn’t get my head around how you would interpret the city (once the biggest industrial town in England, but now a pale shadow of its former self, thanks to the Tory/ Thatcher government of the late-70s and throughout the 80s). As you recount in Comics and Stuff, you and I visited the Talbots, and went around many of the sites represented in Alice in Sunderland. We also visited the museum, which at the time had a focus on the mining heritage that has now disappeared (again, courtesy of Thatcher and the Tories). I am very interested in your impressions of Sunderland, coming from a radically different national context yourself. Was it quite an alien, discombobulating experience?

Henry Jenkins

Well, as I’ve shared before, the first time I read this book I had a crisis of faith mid-way through when Talbot suggests that perhaps Sunderland doesn’t exist. I had been taking it on faith, never having heard of Sunderland before, and not bothered to look it up on a map, and I was drawn by Talbot’s account by the historical and literary richness of this place I had never heard of.

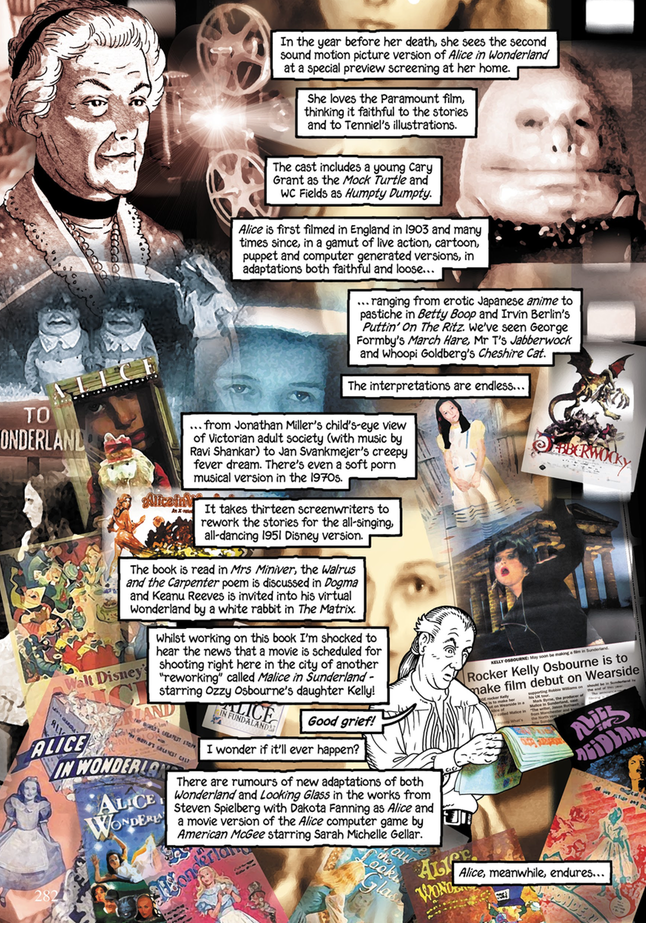

Talbot’s device of the one “fake story” in the sealed envelope encourages us to question what we are reading. But his account uses Sunderland as a microcosm for all of the great movements of British history, going back to the Age of Reptiles, and finds a way to link in such a broad array of culturally significant works of art, literature, and media.

Having had this lapse of faith, I needed to ground my reading of this book in reality, I wanted to trace some of the routes Talbot takes in the book which is, among other things, organized by his character’s movements through space. As for the town itself, it was not “alien” or “discombobulating,” but it is a very British place, representing a different kind of Englishness than what motivates Anglophile trips to Londontown or Oxford. I had already been to Birmingham, Manchester, Blackpool,and Liverpool, all of which evoke a more working class view of British life, though each is better known in America than Sunderland. Regardless, I had a blast and was much appreciated of what you and the Talbots were willing to share with me of the place.

William Proctor

You describe Talbot’s Alice in Sunderlandas “a hypertext in printed form.” What do you mean by this?

Henry Jenkins

I was trying to get at the way that the book is structured through associations and digressions, that it works on multiple levels simultaneously and that on different readings I have tended to favor one level over another. Is it about local history and geography, national culture, the nature of death and decay, the cultural status of comics, an account of how Lewis Carroll was inspired to write Alice in Wonderland or a case for a multicultural Britain, among just a few of its core themes and structures? All of the above and much more. And that’s why it might be interesting to reconfigure the content to trace through the various strands.

Talbot is insistent that he does not feel that the story would work in hypertext because there is a deep logic to the sequence in which things unfold and that giving readers total freedom to move through links across its pages would result in a less satisfying dramatic form. I can see that and I ultimately bow to his claims about his own text. But I have had so many students, who are studying how to craft interactive stories, say that they learned a ton from following how he leads readers from place to place, thematically, temporally, and geographically, all at the same time.

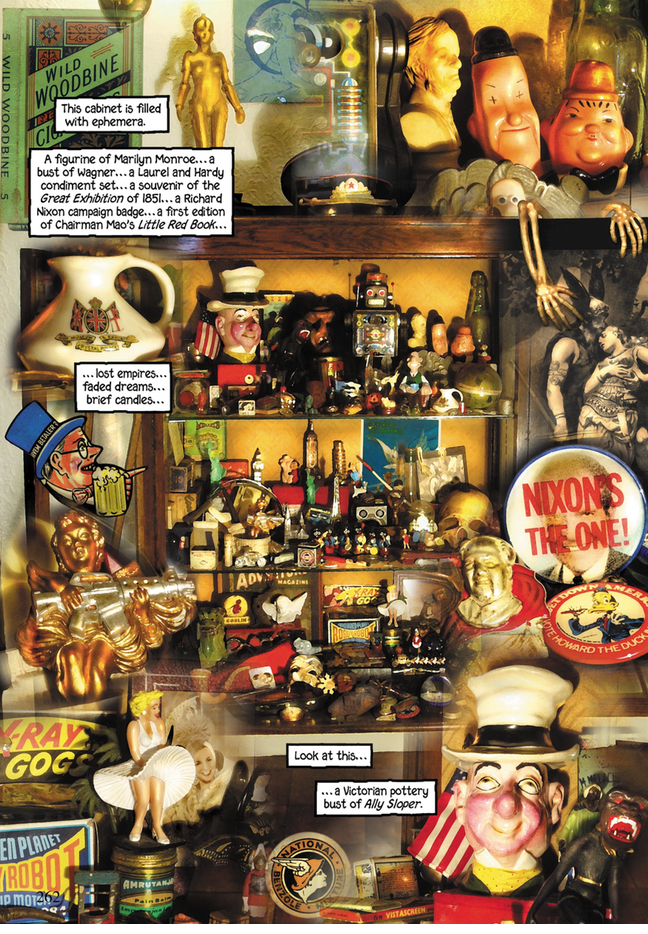

In the context of the book, I end up discussing it in relation to three Victorian era practices which also rely on an aesthetics of accumulation—the cabinet of curiosities, the music hall, and the collage. Each seems more appropriate, in the end, for talking about how Talbot draws on forms of storytelling appropriate to the context where the core events of this pictorial essay occurs.

Michael Saler

You discuss the “enchantments” of material culture and of collecting (highlighted by the work of Kim Deitch, Bryan Talbot and Emil Ferris) as well as their “disenchantments” (highlighted by Seth and Chester Brown) and conclude on an ambivalent note yourself: “Sooner or later, our stuff will engulf us.” You show that ambivalence is innate to collecting, just as complementaries are intrinsic to sequential art. How might the disenchanting aspects of collecting be challenged by digital culture, with the cloud as the ultimate repository of things? Might we be more willing to let go of the material object as we become accustomed to thinking of existence in virtual as well as material terms? And might there be a fundamental “manna” to tangible objects that virtual representations will never have: have collectibles become our secular reliquaries?

Henry Jenkins

One of my points of entry into the book was Will Straw’s writing about the new forms of historical consciousness that we find in digital spaces. He was arguing that people there can gather around a particular bit of cultural real estate, assemble information, contest theories, share finds, build archives and encyclopedias, and so forth. I traced this through in terms of the 1939 New York World’s Fair (another shared obsession) and its relationship to the forms of Retrofuturism which informs Dean Motter’s work. And I got the ultimate fanboy honor—Motter chose to run a version of that essay in his graphic novel, Terminal City. I ended up not writing as much about Straw’s work in Comics and Stuff, but I think his ideas about historicity shadow the argument of the book. If we think of communities who gather around and make meaning from meaningful objets, then networked communication is a huge asset for such relationships.

That said, as a collector, I want to own things, especially media, which is probably the primary focus of my collecting. On one side of my desk is a wall of comics—including some of the earliest comics I read—and on the other wall are DVDs. As a child, I used to lay awake at night and imagine which movies I wanted to own, assuming scarcity in a world of celluloid prints. Each selected film was precious. Now I am a completist. I have all of the surviving works of Alfred Hitchcock (and am starting on Alma’s films). I have been collecting the films of John Ford, Frank Capra, The Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin… I believe anything is better in a boxed set. I don’t want to trust the cloud or more importantly, some streaming service to provide my access—“on demand”—to such materials. They are not really “on demand” when they are on the streaming services one day and gone the next month. And the same thing happens on YouTube for different reasons -- a collector posts some rare film one day, then the next time you look for it the film’s gone because the owner got a take-down notice. I dig the idea of the “infinite jukebox” -- I really do -- but it is a long way from being a reality and until it is, I want to own these things. And getting deeper into the psychology of the collector, I want to display them. I am about at the limits of this -- until now, I have kept all of the DVDs in their boxes but I am running out of shelves and need to find a more compact way to house some of them if my collecting habits are going to continue.

So, yes, in some senses, the digital changes the context of collecting from a solitary to a more networked relationship and it gives us access to things we could never find before. In the book, I contrast the responses of Seth (who values the search as an adventure) and Kim Deitch (who starts many of his stories by buying things on e-Bey and then starting to trace their secret origins through systematic research). The two express the ambivalent response of the collector to the changes digital media is bringing to their lives. But few collectors are ready to trade access for ownership any more than I do. And so far, we are talking about mass produced items. Add scarcity to the mix. Add uniqueness and historical significance to the mix. Add what Walter Benjamin called “aura.” Add the connection of this object to a loved one (as Joyce Farmer or Roz Chast are discussing). And we want to own the thing itself -- not just look at it on our computer screen. I want toownthe school bell that my great grandfather used to call his students together. I want to ownmy father’s copies of the Pogo books. And I do. The problem is that the more my expertise grows and my interest expands, the more things I must own and I am running out of space.

Interviewers

Ichigo Mina Kaneko is a PhD candidate and Provost’s Fellow in Comparative Media and Culture at USC. She holds a BS in Media, Culture, and Communication from NYU and was formerly Covers Associate at The New Yorkerand Editorial Associate at TOON Books. Her research focuses on disaster and speculative ecologies in postwar Japanese literature, comics and cinema.

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Comics, Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is the co-editor of the books Transmedia Earth: Global Convergence Cultures (with Matthew Freeman) and the award-winning Disney's Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion, and Reception (with Richard McCulloch). William is a leading expert on the history and theory of reboots, and is currently preparing his debut monograph on the topic for publication, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia for Palgrave Macmillan. He has also published widely on a broad array of subjects including Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, Star Trek, Star Wars, and other forms of popular culture. William is also co-editor on the forthcoming edited collection Horror Franchise Cinema (with Mark McKenna) and he is associate editor of the website Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Michael Saler is professor of history at the University of California, Davis, where he teaches modern European intellectual and cultural history. He is the author of As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (Oxford University Press, 2012) and The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground (Oxford University Press, 2001); coeditor of The Re-Enchantment of the World: Secular Magic in a Rational Age (Stanford University Press, 2009) and editor of The Fin-de-siècle World (Routledge, 2015). He is currently working on a history of modernity and the imagination.