Comics and Stuff: The Interviews (2 of 4)

/Michael Saler

You state, “I hope to contribute a new conceptual and methodological vocabulary for thinking about graphic novels.” Many of the categories you explore – material culture, collecting, nostalgia, history and memory – are the explicit focus of the “graphic novels” you analyze so insightfully. How might your approach help us to revisit the superhero comics that have been studied in more traditional ways? Given Lee and Kirby’s own penchant for self-referentiality and nostalgia, for example, how might The Fantastic Four be understood using the insights you provide inComics and Stuff?

Henry Jenkins

Let me be clear that I am not an expert on Kirby, Lee and the Fantastic Four. I am not the person to do this work. But let me point in the right direction. We might start with Kirby’s extraordinary splash pages, which are, like the work of Harvey Kurtzman or Will Elder which I discuss briefly in Comics and Stuff, are great examples of scanability in comics. Often, theyare focused on actions occuring across the full space of the page. We generally would look at this panel in terms of Kirby’s dynamism, the kinetic force of Captain America smashing through the door. What happens if we decenter our gaze and focus on the bricabrac being thrown about here? Some of it is fairly generic, other parts of it are pretty distinct and on further focus, become points of interest in its own right. Are these objects we could trace across the book? Do they accrue meaning and significance for the character or for the author? Do they help us map the world where the comics take place? Or are they artistic flourishes?

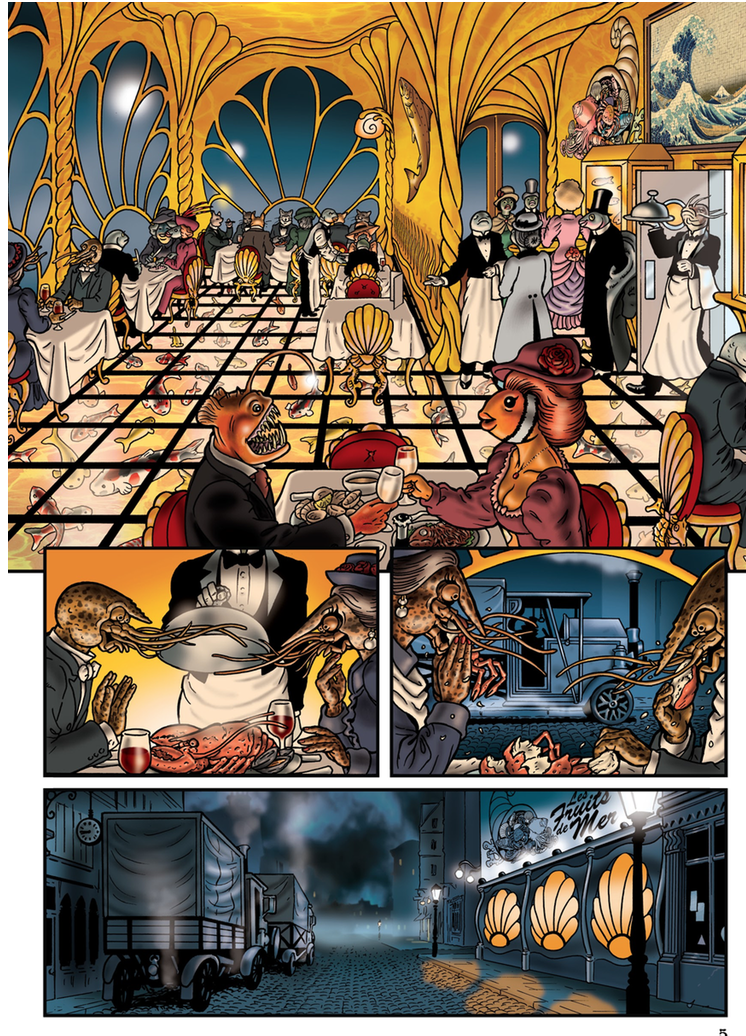

We might also think about the whole phenomenon of Kirby-Tech which I reference in passing in Comics and Stuff: the idea that Kirby adds lots of details to his design of certain mechanisms and technologies, which helps make them seem more concrete to the reader. Here, we see an example from The Fantastic Four. See I did get there. Yet, these technologies seem designed for the quick impression and they become less plausible (but more fascinating) if we study them closely. They operate differently say that the details I discuss in relation to Bryan Talbot’s Grandville universe, where he has carefully worked through a steampunk future occupied mostly by anthropromorphic animals. I use this page as an example in Comics and Stuff. The more we study the details here, the more the world comes to life for us, though also, the funnier his play with anthropromorphism becomes.

Finally, I find myself thinking about those moments where we see the superhero as collector. I am thinking about Superman with the bottled city of Kandor, which always fascinated me as a kid, or the various objects gathered in the Bat Cave and the Hall of Justice. Some of these things have history -- point us back to specific stories, some of them are fascinating yet are given no backstory. What’s striking is how consistently some of these details (The giant Joker card, the oversized penny, the dinosaur, in the case of the Bat Cave) surface across generations of writers and artists, suggesting that they emerge from the mythology surrounding the character but do not reflect the personal obsessions of their artists. And that would be one way to shift the focus of meaningful objects -- towards a study of what the superheroes themselves hold onto from their adventures, why these objects and not others, and how we come to accept these objects (bizarre as some of them may be) as recurring background details.

I am not sure I got at all the parts of your question, but as I said, there are others out there who are more immersed in the analysis of Jack Kirby’s work than I am. As for Stan Lee, I used to say—every comics fans should here him talk once.

William Proctor

On page 3, you casually throw in the term ‘auteur’, as if it is axiomatic and requires no explanation. What do you think of the problems associated with the term—thorny concept that it is—and how might it apply to comics given that the term originated in film criticism? Do you believe that graphic novelists deserve the auteur appellation while mainstream comics writers do not? What impact does this have on the cultural distinctions identified above?

Henry Jenkins

Let’s be clear -- the auteur theory originates in film but it’s really just the French term for author and that discourse goes back a lot further in relation to books. So the most simple claim is that graphic novels, like other books, have authors, and in the case of most of the books I discuss inComics and Stuff, the writer and artist is typically the same person making some of the counter-arguments about film auteurs -- that film is a deeply collaborative medium -- less convincing here.

Accepting the concept of the auteur is part of the Faustian Bargain -- all arts which have gained cultural respectability have had to make claims about the author or the artist as part of the price of admission. In comics, such arguments go back at least as far as “The Good Duck Artist” (i.e. Carl Barks before he was named) or perhaps Lynn Ward, as he lent his cultural reputation to graphic storytelling or Winsor MacCay and George Herrman when they were celebrated by Gilbert Seldes. In other words, like it or not, that ship has sailed many decades ago.

I also would point out the ways that the auteur critics helped to elevate many popular genres, such as the western, the musical, the melodrama, and the film noir, which had previously had some disrepute, just as contemporary comics creators are actively insisting that we pay more attention to children’s comics or horror comics or early comic strips. That was really the parallel I was trying to make here. And the auteur critics were interested in moments where the artist was at war with their material, that is, the places where the artist expressed themselves through their reworking of commercial genre conventions and within studio constraints. Again, the parallels with the struggles over, say, authorship within superhero comics produced by the two big brands seem strong.

That said, I also draw on the mise-en-scene critics, such as V. F. Perkins, who said we should pay attention to how characters got defined through the details of their setting, an approach that seems especially well directed towards my focus on comics and stuff.

William Proctor

You observe that the term ‘graphic novel’ is ‘problematic.’ Roger Sabin has written that the term was ‘an invention of publishers’ public relations department’ that sought to ‘sell adult comics to a wider public by giving them another name: specially by associating them with novels, and disassociating them from comics’ (Sabin 1993, 165). What are your thoughts on the genre being named ‘comics’ and do you think its association with humour and ‘kid’s stuff’ is the primary reason why comics have remained in the cultural gutter for so long in the US?

Henry Jenkins

Let’s accept that the term, graphic novel, is a marketing phrase but also part of Spigelman’s “Faustian Bargain,” allowing the curators, educators, and critics to call this something other than comics and thus allowing them to have a face turn in their relationship to the medium. (Not to be pedantic, but comics is a medium and not a genre, as Scott Mccloud has demonstrated, and that’s why I think the problematic reputation of superhero comics has to do with the genre and not comics per se.)

Douglas Wolk says that what distinguishes comic books and graphic novels is “the binding.” But I make the case in my book that the nature of the binding matters -- comics were going to be treated as trash as long as they were published on cheap paper that was not meant to last beyond a few readings and thus disposable. The fact that graphic novels are now bound in hardcover and meant to reside on library shelves for decades represents a significant change in status. The fact that they were perceived as a children’s medium and thus something that people “outgrew” does not help, nor did it help that they were perceived as targeting the “semi-literate” rather than understood as tapping multiple literacies. As I outline in the introduction, many things needed to change before comics achieved the cultural status at least some graphic novels enjoy today.

William Proctor

It is fascinating that the differences you illustrate in commercial terms between top-selling mainstream comics (or in the vernacular, ‘floppies’) compared with graphic novels (and to a lesser extent, trade compilations). As you state, comparing single issue sales, which are distributed to comic specialty retailers, with graphic novels on the New York Times best-seller list and “a different pattern emerges.” What do you think this teaches us about the market?

Henry Jenkins

Comics sold in speciality shops and graphic novels sold in bookstores are appealing to two different audiences: there’s almost no crossover between the top selling titles in the two markets. Superhero comics still dominate the Diamond List (with limited room for other genres); the openness to other genres grows as we look at bound compilations sold through the direct market and then the tide shifts towards more realism and autobiographical, historical or journalistic stories once we get to the bookstore circuit. And it’s worth noting that in most cases, bookstore sales swamp direct market sales, just because they are reaching a larger audience. This is the paradox: ‘alternative’ comics now outsell “mainstream comics.” As comics become graphic novels, there is a tendency to shed their relationship to the pulp genres from which they originated and to move towards the kinds of literary genres that appeal to bookish people. The graphic novels which get taught in Literature classes or get nominated for book awards follow the genres and narrative tropes, get evaluated by the same criteria, as the other works that are receiving this same recognition. We can go back to what I said about Fun Home -- as good a book as it is, there are places where it seems to be pandering to the hit Literature professor who wants to add a splash of color to his Freshman survey class.

Ichigo Mina Kaneko

I’m really interested in how you discuss collecting as a material practice but also a “structure of feeling,” drawing upon the work of Raymond Williams. Many of the comics you look at feel very intimate in both their storytelling and the stories they tell, conveying relationships to things in intensely personal ways. Do you think comics as a medium allows for particular intimacies to emerge between artist and reader? Are comics inclined toward certain “structures of feelings”?

Henry Jenkins

I do not think comics as a medium are necessarily inclined towards certain ‘Structures of Feelings’. We need only look at the fairly significant shifts in the tone of superhero comics through the years to see that even within a given genre, comics are more responsive to shifting structures of feelings within the culture at large. But it is quite possible to see something shared across a certain school of comics at a particular historical juncture.

That’s the whole point of Williams’ concept: the culture shifts in ways that are hard to describe, but which we feel, we recognize, and we respond to. A certain affect becomes part of how we remember a historical moment and link together works across artists and perhaps across media.

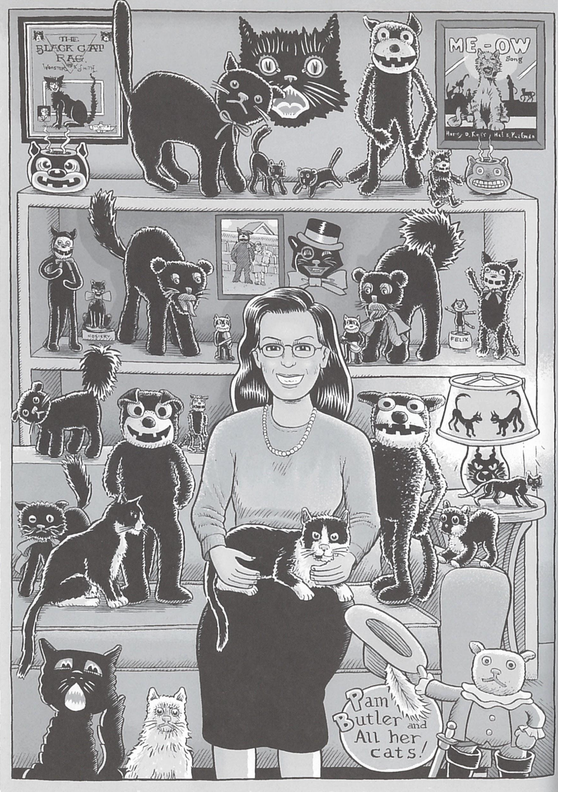

For many of these collector artists, there is a certain nostalgia for the past -- a longing for older things, even as there is often a critique of the historical context that gave rise to those objects in the first place. We can see both Seth and Kim Deitch as dealing explicitly with those conflicting feelings as they relate to the popular culture of the early-to-mid-20th Century. They are drawn to the aesthetics of that period, yet they are clear they would not have liked to live during that era. The result can be a certain shame or pathos which gets expressed in some of these works. Seth depicts himself as crippled by his longing for a lost era, where-as Deitch depicts himself as drawn to conspiracy theories and occult speculations as he seeks truths about the past that can no longer be recovered.

A different kind of sadness surrounds the passing of the prior generation which impacts the works of Carol Tyler, Joyce Farmer, and Roz Chast and for Tyler in particular, there is a recognition of the toxic damage the “greatest generation” brought in their path because of their unprocessed, “bottled up” feelings from the war. And finally, these same older materials produce a kind of existential dread that runs through Jeremy Love’s Bayou, since there is no place for a black author in that world, even through acts of nostalgic imagining. He has no longing for that era, even as he reproduces it beautifully in his work. So, it is hard to put this structure of feelings into words, except that it has to do with working through our feelings for the past, a sense of belatedness perhaps, often masks a sense of distaste for the current moment and an aftertaste of disenchantment.

Interviewers

Ichigo Mina Kaneko is a PhD candidate and Provost’s Fellow in Comparative Media and Culture at USC. She holds a BS in Media, Culture, and Communication from NYU and was formerly Covers Associate at The New Yorkerand Editorial Associate at TOON Books. Her research focuses on disaster and speculative ecologies in postwar Japanese literature, comics and cinema.

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Comics, Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is the co-editor of the books Transmedia Earth: Global Convergence Cultures (with Matthew Freeman) and the award-winning Disney's Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion, and Reception (with Richard McCulloch). William is a leading expert on the history and theory of reboots, and is currently preparing his debut monograph on the topic for publication, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia for Palgrave Macmillan. He has also published widely on a broad array of subjects including Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, Star Trek, Star Wars, and other forms of popular culture. William is also co-editor on the forthcoming edited collection Horror Franchise Cinema (with Mark McKenna) and he is associate editor of the website Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Michael Saler is professor of history at the University of California, Davis, where he teaches modern European intellectual and cultural history. He is the author of As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (Oxford University Press, 2012) and The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground (Oxford University Press, 2001); coeditor of The Re-Enchantment of the World: Secular Magic in a Rational Age (Stanford University Press, 2009) and editor of The Fin-de-siècle World(Routledge, 2015). He is currently working on a history of modernity and the imagination