Comics and Stuff: The Interviews (4 of 4)

/William Proctor

Personally—and thanks to your recommendation—I have found Emil Ferris’ My Favourite Thing is Monsters one of the most emotionally-engaging, beautifully illustrated, and profound graphic works of the twenty-first century hitherto. What first drew you to the book, and what was its impact? How did it affect you on a personal level?

I saw a page from the book -- the one which is on p.191 -- reproduced along with a short review in Entertainment Weekly and felt an urgent need to read it because of my own personal experience growing up as part of the Monster Culture of the mid-1960s. Her world is so very different from mine and yet we had a strong connection through our common fandom. I fell for it hard and wrote that chapter within a week of first reading the book, just giving myself over completely to the project of re-reading and annotating the work. I was and still am nervous about discussing a work which is only half finished and can’t wait to see the second part, which keeps getting delayed.

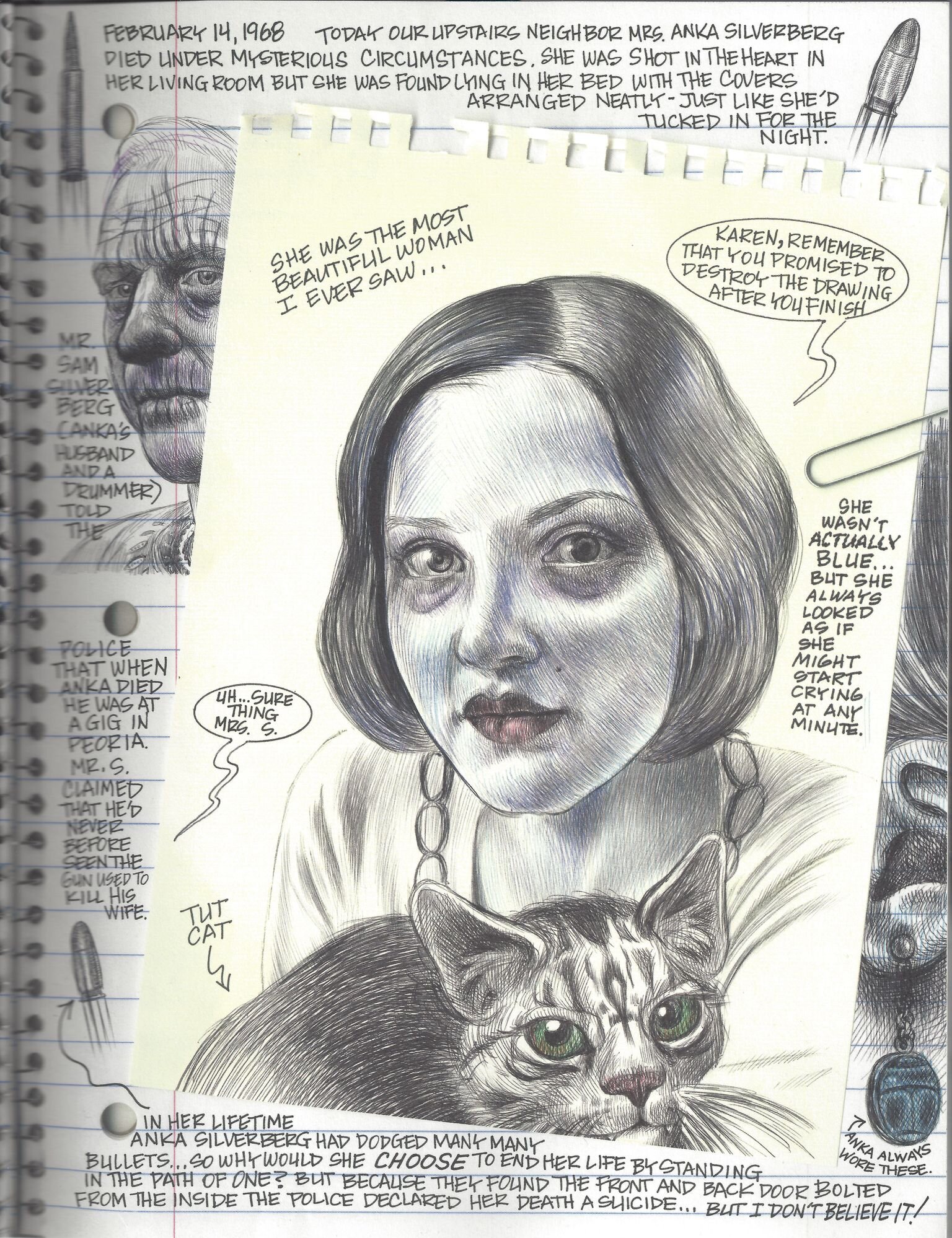

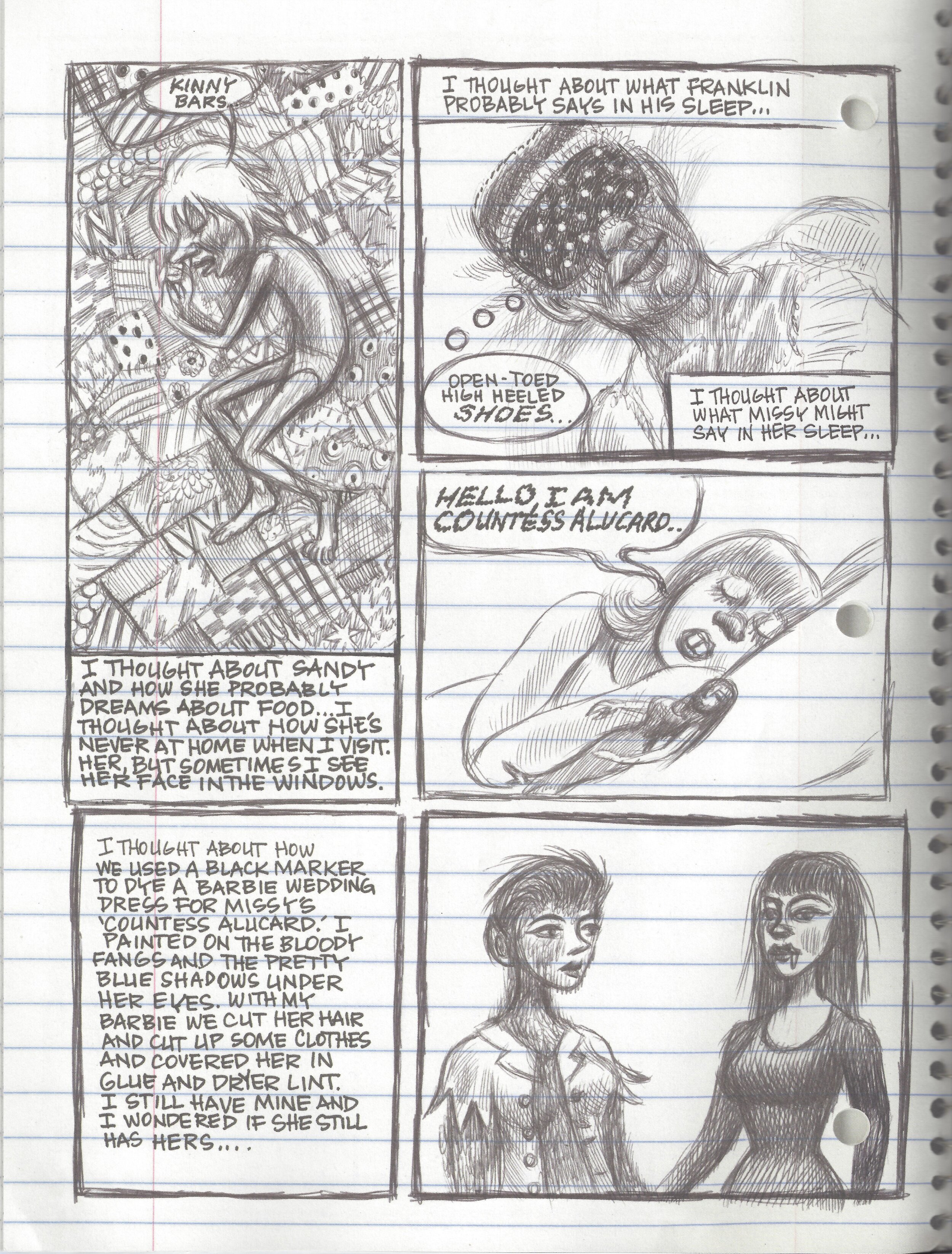

On the first reading, I could not figure out how to make it work in terms of the core themes of the book. The main character Kare does not have many material objects of her own due to her poverty, and the book seems skeptical that we should put faith in things, rather than asserting ownership over images which can be reproduced on the page or through imagination. I came to see this anti-materialism as part of its message and was particularly drawn to the ways the character is shown appropriating and transforming everyday materials -- from bic pens to macaroni, from old school papers to Barbie dolls -- in the course of claiming fanship within monster culture. I also struggled with the title which did not seem to make grammatical sense until I realized that Monsters were her “thing” (her conceptual frame) rather than multiple things that she gathers around her.

I was also excited because the book helped to break down a binary gender distinction that seemed to be taking root in my book -- the idea that male comics artists mostly wrote about the experience of being collectors where-as the female artists were more interested in inheritance as the over-arching theme in their relationship to stuff. But Monsters, alongside Carol Tyler’s account of her teenage Beatles fandom, gave us an alternative set of images of female fans whose collecting was more aspirational and transformational than fully materialized. Once I worked through those challenges, the chapter largely wrote itself, allowing me to dip into the literature around monster movies and in particular, monster fan culture.

Ichigo Mina Kaneko

In your discussion of Emil Ferris’ Monsters, you discuss how Kare mobilizes “stuff” in a transformative way. Not only does she have a different relationship to ownership, but she creates a space of belonging for herself in a world where she doesn’t belong—where “things” often inscribe normative expectations of race, gender, able-ism, etc)—by redrawing her surroundings and thinking/feeling with monsters. It seems to me there is an interesting intersection here with your discussion of comics and memory via Chris Ware when he says, “A cartoon is not an image taken from life. A cartoon is taken from memory. We are trying to distill the memory of an experience, not the experience itself.” Do you think memory in comics encourages a distinctive participatory reading practice? How do comics—or “stuff” in comics—help create a shared sense of belonging that may differ or overlap from that of say, “stuff” in cinema?

Henry Jenkins

That is a really interesting question and since I used that Ware quote in one of your Quals questions, turnabout seems fair play. In some ways, the mere fact that we are reading a comic, when doing so is such a minority practice, means that we have a different relationship to the medium and what it represents than we do when we enter a movie theater, especially to see a big blockbuster. When I go to my local comic shop, I feel a sense of belonging, a solidarity with the other customers, and an especial bond to my dealer, because we all have that in common -- we are there because we read and one presumes, enjoys reading comics. Many have commented how often comic studies writers drift back to their childhood or adolescent discovery of the medium at some point in their writing. So, yes, flipping the page of a comic, even one we have never read before, can bring out a burst of memories for us.

Ware means something a bit more abstract that that -- there’s a kind of fuzziness about the ways comics represent the world -- not as sharp and clear as a good photograph and comics somehow captures the fading of memory as we struggle to bring back to our mind what our room looked like when we were in seventh grade. Some features are very clear, others totally forgotten, and the stylization and abstraction of hand-drawn images seems to be groping towards and never fully capturing the world that is in the head of the artist.

I characterize Monsters as an anti-materialist book, which has much to say about our relationships to things like the paintings in the art museum that we can not fully possess as our own, that talks about roles, such as that of the monster, that we never can fully occupy. Kare as a character performs what Michel De Certeau called as “the art of making do.” In this case, she makes do with the materials at hand and in many cases, she does create art from the most mundane materials, like the riot of anti-romantic monsters she draws on an old math paper.

As a reader, I certainly feel some degree of alignment with Kare’s world view -- as someone who was an obsessed monster fan during that time period, who felt cut off from the puppy love courtship games that obsessed my school in sixth and seventh grade, as someone who hated math class and often daydreamed and sketched, and as someone who hung out with other outsiders with whom we formed our own rituals and identities through our relationship with popular culture. At the same time, I did not experience the broader range of intersectional exclusions that shapes her life.

William Proctor

My Favourite Thing is Monsters is designed as if drawn in biro on scraps of note-paper, as if scribbled in a school book or an A4 writing pad. Was this an intentional design by Ferris, or was it actually created this way? Do you know if Ferris used software to give the impression that it’s more organic in its aesthetics? What effect do you think Ferris is aiming for?

Henry Jenkins

Good question and I do not know 100 percent. My impression from the interviews I’ve read is that she did the book using the materials as depicted. Add to this the fact that she did so while struggling with disabilities which made it painful for her to work with her hands for a long period of time and that she did so, at least part of the time, while homeless and destitute, not to mention a single mother. The fact that she was able to produce such exquisite work under these circumstances is nothing short of astonishing, as is the fact that this was the first substantial comics work that she had done. So, yes, it is a staggering work by any criteria you want to throw at it. Under these circumstances, we should cut her some slack about the long wait for part two. In terms of what to make of these choices which surely made producing this work that much harder on her. I do think her artistic choices amplify the anti-materialism and transformative nature of her graphic storytelling. She has chosen to frame her story as a young girl’s sketch book, even though no girl of this age has the virtuosity to be able to conceptualize and generate this work. Focusing our attention on what can be done with household materials also calls attention to the other ways that Kare lives by what Michel De Certeau would call “the art of making do.” She takes advantage of what the world gives her and transforms it into an expression of her personality and worldview.

“Monsters” provides her with a metaphor to reflect on so many aspects of her identity (her gender, race, sexuality, economic situation, and her mother’s declining health). And I keep coming back to the moment when she turns her Barbie dolls into Dracula’s Daughter (the few Lesbian image to enter her world) and Wolfman (her own persona) as a way of transforming manditory femininity and hetrosexuality into something different. Her character survives by changing her conditions through transformative use of everyday things. And so, apart from the artist’s own desire to experiment with comics form, the book’s technical approach helps to direct our attention onto the limits in the protagonist’s life and what she does about them.

Ichigo Mina Kaneko

Has the changing format of comics (“from disposable to durable”) changed the way you collect them? Similarly, how has the process of writing this book transformed or influenced your own relationship to collecting?

Henry Jenkins

Most of my comics are no longer in long boxes. I now display them on a row of bookcases in my study. I still buy mostly monthly floppies rather than graphic novels -- when I can. And this is an old habit I am finding hard to break -- they take up much more shelf space than bound editions and often look much messier. I tell myself that I want to keep up with the stories as they unfold but that rarely happens and I end up binge reading a year’s worth of a given title in a sitting. In some cases, I do like to read the letters and other back matter that are often cut from the graphic novel versions once they are compiled. I have written several essays now about how Robert Kirkland helped to map the rules of his zombie universe in his response to readers in The Walking Deadseries or how Kelly Sue Deconnick (Bitch Planet) and Matt Fraction (Sex Criminals) construct a informal public of their readers as they work together to change how they thrink about gender and sexuality. So, yeah, I buy the monthly issues for the letters, that’s the ticket! I also pref er to buy print comics in whatever format to digital comics. I value the materiality of comics and any number of recent comics reward us by making imaginative use of the printing process itself, whether it is Chris Ware’s Building Stories or Joe Sacco’s The Great War.

To tackle your second question, I wrote the book in part to work through my ambivalences regarding my own collecting and accumulation tendencies. When we acquire more great stuff than we can display, the result is clutter. At that point, pride gives way to culturally induced shame The process of writing the book opened up far more questions for me than it resolved. I try to state some of those questions in the book’s conclusion. On the most basic level, I am working through my own pack rat instincts as I reach a point where I can no longer hold onto as many things from my past as I would like. But that closing chapter hints at something else.-- the cultural baggage which needs to be discarded if we are able to learn to respect each other within an society that is transforming as a result of increased diversity at all levels. We can not simply build monuments to the way things used to be and we certainly should not be taking souvenirs with us to recall older attitudes towards race, gender, sexuality, or nationalism. We need to move beyond the comfort of surrounding ourselves with familiar things (or people) when it comes at the cost of someone else’s dignity. On paper, this sounds obvious, but it can be harder for people to let go of things than it sounds.

Michael Saler

Throughout the book I was aware of how personally invested you were in many of the issues you explored, just as you analyzed the emotional import of these issues to the individual creators; your Epilogue made this explicit. Each chapter of the book was in some ways a mise-en-scène of your own preoccupations over a lifetime of reflecting on how mass culture is used to create and recreate personal and social worlds. How would you relate this book to Textual Poachers, in terms of the evolution of your own thinking about these or other issues?

Henry Jenkins

You are very perceptive. This is in many ways my most personal book, even if I withheld autobiographical details for the introduction and conclusion. Each of these artists spoke to me because I recognize something of myself in their work. We are fans and collectors of many of the same things, which is part of what gives me the knowledge set to be able to address the meaningfulness of the objects they represent in their comics.

We do not always relate to those materials in the same way -- I already flagged the differences in how Emil Ferris and I experienced monster culture, say -- but having had those experiences, I recognize what she is talking about. You can, for example, see bits of my early work on variety performance traditions (What Made Pistachio Nuts?) creep into my discussion of Alice in Sunderland, for example. My childhood experiences as a white southerner growing up in a segregated Atlanta during the civil rights era shaped how I responded to Bayouand especially the ways that he evoke Br’er Rabbit.. The past few years has required me to work through traces of the Lost Cause ideology that I did not know I still had. The issue of going through your parent’s stuff after they die -- as part of the process of letting go -- speaks to me on an immediate emotional level and can not help but inform what I say about C. Tyler, Roz Chast, and Joyce Farmer.

But you asked specifically about Textual Poachers. I pointedly have not written about the fan as collector until recently. I lacked a conceptual model to discuss this aspect of fandom. It came too close to the critiques of commodity culture or fetishization that fans are often implicated in. I spent time in dealer’s rooms at cons, but I did not write about them. But with this book, I offer an implicit defense of collecting as a form of memory management, media-making, and self-fashioning. I talk about Kare, the protagonist of Monsters, in terms of her appropriative and transformative use, concepts that come straight out of fandom studies. I reflect on Seth’s self-representations in relation to the stereotypes I identified in Poacher’s opening chapter and yet I find myself more forgiving when these tropes are deployed through self-representation, rightly or wrongly, and see comics as a space where fans are at least sometimes represented in sympathetic terms. I am not a Beatles fan, let alone a pre-teen girl, and yet I recognize the anticipation, the social rituals of fandom as Carol Tyler shares his experiences in Fab4Ever; I read them in relation to Barbara Ehrenreicht et al’s analysis of Beatlemaniaas the start of a sexual revolution for women. I discuss Birmingham and subculture theory in relation to Tyler’s fights with her father over her adoption of his old military garb as part of her counter-cultural identity in A Soldier’s Heart.

I am not sure I can sum it all up, but I kept stumbling into my earlier writing as I was doing this book. In some ways I must be feeling old, because it does have an elegiac quality, as if I were summing up my life’s work. But, have no fear -- I’m not dead yet. I am hard at work on another book, which is if anything even more personal, since it deals with the cultural experiences of the Baby Boom generation, structured around texts which meant a lot to me as a child. And in some cases, being the packrat I am, I am writing my analysis using the battered copies of Dr. Seuss that my parents gave me to read as a child -- not quite first editions, but early editions. So, behind the scenes, my collection is still going to be very much in display in this book.

Interviewers

Ichigo Mina Kaneko is a PhD candidate and Provost’s Fellow in Comparative Media and Culture at USC. She holds a BS in Media, Culture, and Communication from NYU and was formerly Covers Associate at The New Yorkerand Editorial Associate at TOON Books. Her research focuses on disaster and speculative ecologies in postwar Japanese literature, comics and cinema.

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Comics, Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is the co-editor of the books Transmedia Earth: Global Convergence Cultures (with Matthew Freeman) and the award-winning Disney's Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion, and Reception (with Richard McCulloch). William is a leading expert on the history and theory of reboots, and is currently preparing his debut monograph on the topic for publication, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia for Palgrave Macmillan. He has also published widely on a broad array of subjects including Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, Star Trek, Star Wars, and other forms of popular culture. William is also co-editor on the forthcoming edited collection Horror Franchise Cinema (with Mark McKenna) and he is associate editor of the website Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Michael Saler is professor of history at the University of California, Davis, where he teaches modern European intellectual and cultural history. He is the author of As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality (Oxford University Press, 2012) and The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground (Oxford University Press, 2001); coeditor of The Re-Enchantment of the World: Secular Magic in a Rational Age (Stanford University Press, 2009) and editor of The Fin-de-siècle World (Routledge, 2015). He is currently working on a history of modernity and the imagination.