Comics & Stuff: The Interviews (1 of 4)

/My newest book, Comics and Stuff, was released last month by New York University Press. Creating this work—my such solo authored book since Convergence Culture—was a labor of love, done over many years, on time borrowed from other, often more pressing projects. As I release the book, I wanted to shift the microphone here—first, to William Proctor, the blog's Associate Editor, and also to two colleagues and thinking partners, Ichigo Mina Kaneko and Michael Saler—who were among the book's first readers. Over the next week, they grill me hard about various aspects of comics and stuff. Coming soon: An announcement of the schedule for a Zoom Book Club coming up in Zoom, where you will have a chance to ask me questions in real time and where a range of other comic scholars who influenced this book, one way or another, will come, hang out, and share their thoughts about comics and other stuff.

Henry Jenkins

William Proctor

What first attracted you to the concept of 'stuff'? Why do you think the comics medium is especially insightful as a lens with which to analyze our 'stuff'?

Henry Jenkins

This project was started in a bass-ackward fashion. I was invited to propose a digital book concept to the Annenberg Innovation Lab, and I saw an opportunity to explore what comic studies might look like in an interactive book context. I wanted to respond to several challenges in comics studies: first, the problem of reproducing comics for analysis in a book whose format was often smaller than the original publication venue and where it was often too expensive to reproduce color images. This desire led me to focus my initial thinking around questions of mise-en-scene, which is under-emphasized in current comic studies in favor of sequentiality and breakdown.

I started to make an initial list of graphic novels that spoke to me, that had been neglected by other scholars, and that lent themselves into this mode of analysis. As the project continued, I would abandon some artists from that initial list and pick up others, but the core of that list shaped the final book. (If any one is curious, I ended up publishing an essay on Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towersas a stand-alone essay and still have hopes to publish other essays -- one on Dylan Horrack’s Hicksvilleand Sam Zabell and the Magic Pen and one of Ben Katchor with a focus on The Cardboard Valise. Maybe someday. Anyone editing an anthology where they might fit?).

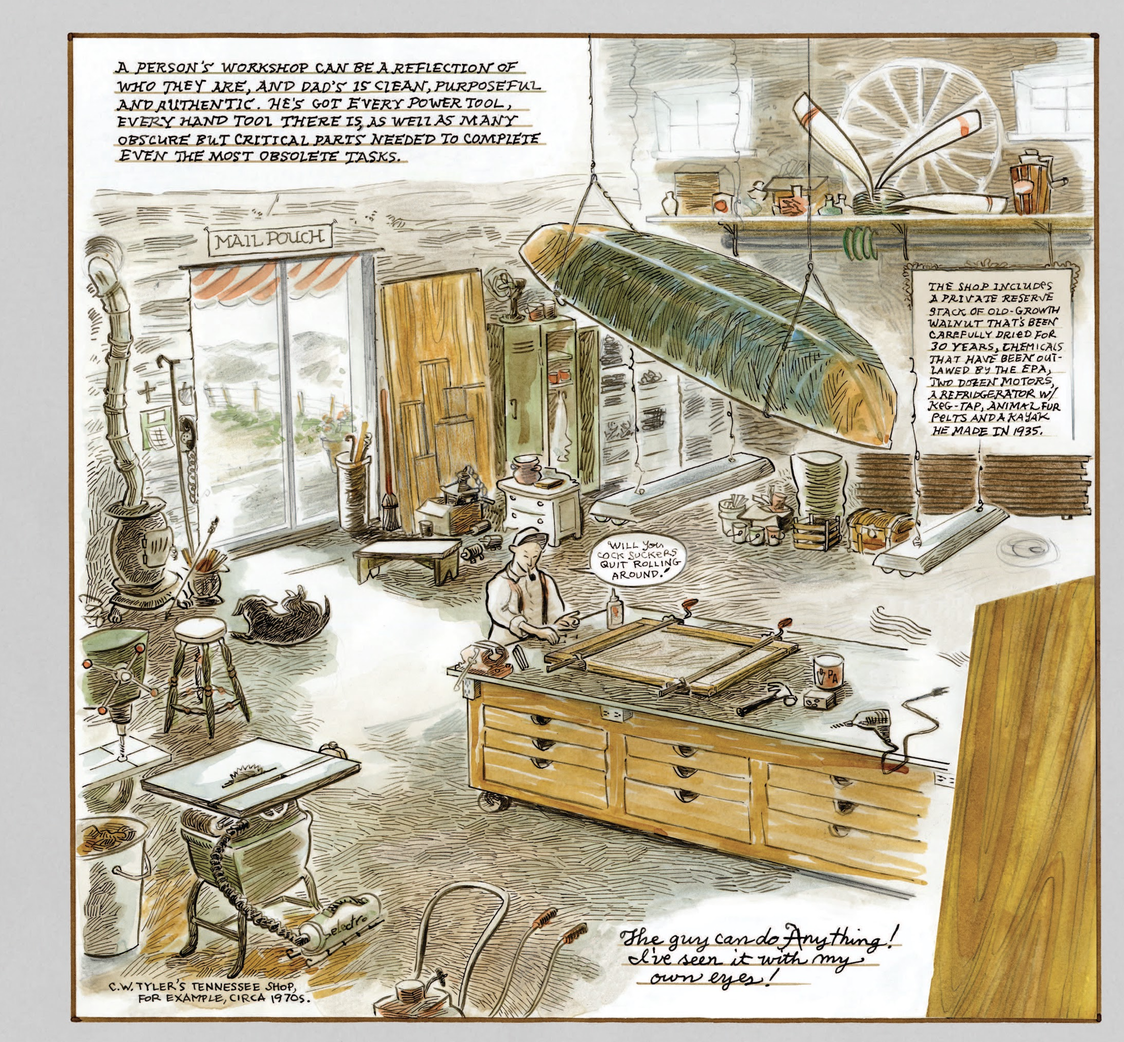

My vision was to release a series of stand-alone essays about different comics artists, one per month, which would be assembled into a single work when they were completed, much as a series of monthly floppy comics might come together to form a graphic novel or in the case of C. Tyler’s A Soldier’s Heart, a series of graphic novels might be gathered into an omnibus. By this point, I was jokingly calling the project, Comics and Stuff. I had my title before I really knew what the book was going to be about. In the end, it proved too difficult to achieve a digital book with the properties I imagined but I clung to the impulse to generate a book around this corpus of materials.

In a playful mood, I did a search one day on Amazon for books about “stuff” and found Daniel Miller’s Stuff, which utterly fascinated me, and it was in reading that book that the core concept started to take shape for me. I am a pack rat bordering on hoarder so the problem of stuff has personal significance to me. I had written an essay some years back about Dean Motter (Mister X, Terminal City), nostalgia, retrofuturism and the collector mentality in comics.

Otherwise, I had never written about collecting despite writing much about fandom through the years and this project offered me a chance to dig into collecting more deeply. And the more I read Miller and outward from him to others (such as Bill Brown) the idea of looking at literary texts in relation to material culture started to grow on me. I was struck by the fact that such scholarship was becoming more common in literature and art history but had not really crossed over, at that time, to the study of popular culture. So, all of this led me deeper and deeper down a rabbit hole, looking at still life painting and other genres that throughout media history had encouraged a focus on material practices and everyday life.

The final key element came when I was in residence at Microsoft Research New England and the team there asked me about comics as stuff. And that was when I recalled that I had already written about comics as stuff for Sherry Turkle’s book, Evocative Objects: Things We Think With. In the end, it seems like my route to Comics and Stuff, no longer a gag title, was over-determined, but it seemed fairly random at the beginnings of this process.

In the end, the book put forward four main propositions:

● Stuff is used to refer to material objects and the emotional investments we make in them, which translates them into our possessions.

● Comics are stuff, once disposable, now more highly valued, and the struggles over their enduring value inform the artist’s perception of themselves as collectors and inheritors.

● Comics depict stuff through their mise-en-scene and such details reflect the artists’ world views in important ways.

● Comics narrate our relations with stuff and the central narratives deal with collecting and inheritance, though the book also explores the recurring theme of material objects (especially toys) being brought to life.

William Proctor

In the opening to the book, you address the ‘Faustian deal’ articulated by Maus creator Art Spiegelman regarding the legitimacy of comics in recent years. Where do you think the medium stands now in reference to comics-as-art? How does this attitude compare with, say, France, where comics (or bande dessinèes) have been viewed as ‘Le Neuvième D’art (the ninth art) since at least the 1960s? It may be surprising to some that France are the second-highest producer of comics in their different forms, with Japan in pole position, and the US in third place. In addition to the examples you give, Sabrina by Nick Drnaso became the first graphic novel to be nominated for the Man Booker Prize, Britain’s most prestigious literary award, and March: Book Three by Andrew Aydin and John Lewis about the Civil Rights Movement won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature in 2016. We can see how cultural distinctions within the medium continue to persist, as well as outside it. The history of comics “as trash” seems to remain for certain comics, while others have been elevated to the status of art. Do cultural distinctions exist for superhero comics, for instance? What maintains these distinctions and do you think they’re helpful?

Henry Jenkins

For me, personally, I think the battle to establish graphic novels as a legitimate art form has largely been won in the Anglo-American context. It may not be as well established an art form here as in France. Some would describe it as a middle brow form of expression here, but the kind of signifiers you describe above have helped to shift its status.

Superheros may be an exception, but they are not the only one: right now, the exceptions are defined by genre and thus not dependent on individual artists and their output. The same bias is attached to Superhero films, even if we’ve now seen Black Panther and Joker get best picture nominations. Again, it has to do with the genre elements which seem alien to a segment of the critical and curatorial community.

But, this takes us back to what makes legitimation a “Faustian bargain.” Respectability comes at the potential price of losing some of the pop vitality of the form, respectability comes with the loss of some of the disreputable and transgressive elements, which is part of what led us to love comics in the first place. Spigelman’s Mausseems to deftly play them against each other -- the funny animals attracting readers who would not be invested in a holicaust narrative and vice-versa. On the other side, I struggle with the literary pretensions of something like Alison Bechdel’s Fun House (at the risk of making a controversial hot-take) where-as the Broadway version was less invested in embracing cultural hierarchies. I’d like Fun House more (I do like it) if Bechdel was less determined to impress me with her good taste. Remember Charlie the Tuna: We want tuna that tastes good, not tuna with good taste.

So far, the Superhero comic’s primary bid for cultural respectability has come through self-criticism so that Watchman has the best claim to having succeeded at the “Faustian Bargain” Spiegelman describes. The recent television series took the superhero genre elements towards historical reconstructionism (the Tulsa bombings) and political satire, allowing it to receive a high degree of critcal praise. The Oklahoma Department of Education has now added the Tulsa bombings to the state history standards off the back of its evocation in Watchman. And Watchman was just nominated for a Peabody Award which recognizes “stories that matter.” It is not the first superhero series to be so recognized—Jessica Jones previously was acknowledged by the Peabody Awards, again a superhero story that matters because of that Faustian deal between social import and pop culture vitality.

Ichigo Mina Kaneko

As you describe in your book, comics are embedded in practices of collecting in part because they themselves were historically ephemeral objects not meant to last. With comics becoming a more durable medium that has begun to form something of its own “archive,” how do you envision comics’ relation to “stuff” shifting? How might the formation of something like a “comics archive” or “comics canon” influence the way these collecting impulses appear in comics moving forward?

Henry Jenkins

I personally am reluctant to see things solidify into a comics canon though there is a very good chance that something like that may be happening. I would be happier with a more expansive notion of a comics archive. The sense of rediscovering interesting and forgotten comics is part of what really excites me about the current moment. It’s great that we are seeing so many older comics put back into print again in hardcover editions that are meant to last, showing respect for outstanding works from previous generations of creators. I love having access to such beautiful editions of Gasoline Alley, Pogo, Barnaby, Little Nemo in Slumberland, Krazy Kat, Basil Wolverton, Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder, and so much more. But a canon is about what gets excluded as much as it is about what gets included. I like inhabiting a world where different comics artists are pimping for their predecessors, trying to get us to pay attention to something they think matters, rather inhabiting a world where -- like contemporary literature departments -- a handful of authors and their works dominate the discussions.

The fact that so many of the artists are collectors of older paper materials contributes to the focus on stuff in their books. So many of the things they draw exist in the real world -- the artists are showing their possessions (and their obsessions) to the world! There’s a thin line in many cases between collecting comics and collecting movie stills or old records or old toys (as Kim Deitch suggests) or mid-century modern bric-a-brac (as Seth shows us). I love that Carol Tyler still has her pre-teen diary of going to a Beatles concert which she can draw on for her latest graphic novel or that Mimi Pond geeked out on our podcast about napkin holders, silverware, and coffee-makers she recalls from her years working as a waitress in an coffee house.

I corresponded recently with Joyce Farmer about the Klu Klux Klan figurine she depicts near the end of Special Exits. She shared, “I gave the 9" plaster statuette of the Ku Klux Klan figure to my son with a careful explanation of how I got it and that it probably belonged in a museum of African-American history. He found it too strange to display in his home and it ended up on a shelf in his garage. After some sort of verbal altercation with his wife about either the statue or me (or both) his wife smashed it on the garage floor, thus ending up in the garbage.” I learned this too late to include it in the book but somehow I was tickled to know what happened to this particular object that appeared in one highly memorable panel.

I have digressed away from your core question here. Insofar as canons create a shared language, a set of meaningful references, things which artists can assume most people know, it may allow artists to shorthand certain ideas and push into new territories. Insofar as canons set limits on what we read, a canon may deter experimentation and exploration of older materials. I am not that worried though, because comic artists are an eccentric and cantankerous lot; they tend to march to their own drummer and they tend to love to debate the merits of old comics. They do not have the herd mentality of the average literature professor.

William Proctor

What encouraged you to exclude more mainstream comics from your analysis? Are there any examples of material culture—‘stuff’—in superhero comics, for instance?

Henry Jenkins

Almost certainly, though there will be differences in how it functions there. I borrow from art history a distinction between Megalographic (“the depiction of those things in the world that are great -- the legends of the gods, the battles of the heroes, the crises of history) and Rhopographic works (“the depiction of those things which lack importance, the unassuming material base of life.”)

Curiously, for art historians, the Meglaographic was historically the domain of great art, while the still life (a classic example of the Rhopographic) tended to be dismissed as humble or domesticated art. In comics, the superhero comic has many elements of the Megalographic (the epic battles, the god-like characters) but has contributed to the medium’s disreputability where-as the turn towards more realistic depiction of everyday life has been part of what has given it artistic status. And in depicting everyday reality, these graphic novels ground themselves in details from our material culture.

I am interested in the ways Paul Chadwick’s Concrete uses such details in a superhero context. These two illustrations show the contrast it establishes between an interest in the interior spaces associated with its characters and a fascination with the natural world, both rendered with great attention to details. My copies of the books are at the office right now and thus out of reach so I am limited to what I can find scanned on the web. In the early chapters, rather than mask his identity, Concrete (and his government handlers) decide to saturate the media with his story, resulting in compassion fatigue and disinterests. Here, many frames show pop culture artifacts in the background that reflect this media strategy, and there’s something to be explored about the celebrity of the superhero through these commodities.

In later stories, we see many details of the natural world, including animals in their burrows, details the characters do not notice but which also exist without regard to Concrete’s actions. This is part of a systematic interest in environmentalism throughout Chadwick’s work, culminating in a series of issues centered around more radical forms of environmental justice activism such as spiking trees. These details often serve to decenter the superhero from his own narrative,contributing to the anti-heroic perspective this comic takes towards the superhero narrative. We might see the artwork as drawing more or less equally on the still life and landscape traditions. I am passionate about Chadwick’s work within the superhero genre and beyond and hope to write about it someday, though even this is from an alternative rather than mainstream superhero title.

I would love to see other examples of how the model of analysis Comics and Stuff offers might work in relation to superhero titles. The challenge there is that for most contemporary artists working for the big two the pressure to crank out pages results in a lack of time to fill in the kinds of environmental details that intrigue the alternative writers I discuss. And the collaborative nature of their output -- that is, the separation of artists and authors means there is often less space for anyone’s personal worldview as a collector, say, to enter the picture. I love superhero comics. I hope readers can point to some good examples there worth exploring more fully. Or perhaps stuff there plays different roles I just have not considered yet. I will certainly offer a No Prize to anyone who shows me the gaps here.

Interviewers

Ichigo Mina Kaneko is a PhD candidate and Provost’s Fellow in Comparative Media and Culture at USC. She holds a BS in Media, Culture, and Communication from NYU and was formerly Covers Associate at The New Yorkerand Editorial Associate at TOON Books. Her research focuses on disaster and speculative ecologies in postwar Japanese literature, comics and cinema.

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Comics, Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is the co-editor of the books Transmedia Earth: Global Convergence Cultures (with Matthew Freeman) and the award-winning Disney's Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion, and Reception (with Richard McCulloch). William is a leading expert on the history and theory of reboots, and is currently preparing his debut monograph on the topic for publication, Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia for Palgrave Macmillan. He has also published widely on a broad array of subjects including Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, Star Trek, Star Wars, and other forms of popular culture. William is also co-editor on the forthcoming edited collection Horror Franchise Cinema (with Mark McKenna) and he is associate editor of the website Confessions of an Aca-Fan.