Return and Renewal: Star Trek: Picard (3 of 3) Djoymi Baker & Roberta Pearson

/Pearson

All of this discussion about the characters and their backstories raises the issue of how well the producers addressed that dilemma of attracting a new audience with new characters. What is the difference between fans like us who know the storyworld and the characters, and a new viewer who has to work harder to understand the rules of the storyworld and for whom the characters will not have that very strong emotional resonance that they have for us?

Baker

It’s an interesting point, whether viewers can connect with the Picard if they’re not already familiar with those characters, whether it’s Seven, or Riker and Troi, or even Picard himself. Brad Newsome gave a review as a non-Star Trek viewer, saying the pilot episode hooked him in regardless.

If you go to Rotten Tomatoes and you just glance over the stats for reviews of the season, the first episode gets 100% but by the finale it goes down to 59%. I’m wondering with a new viewer such as Newsome, who initially felt they had an entry point into this narrative world they had not been familiar with, whether they continued to feel part of the journey.

You’ve written about this with Messenger Davies, that there are often many scenes across the Star Trek franchise where you need that backstory to fully understand what’s going on at least in terms of the way characters are interacting with one another.

Pearson

I think you do. Characters, I argue in the Star Trek book, are constructed through a narrative function, a constellation of traits, a setting and their relationships with other characters that inform who they are and how they act. That’s why I think it’s so hard to reinvent a character like Picard, if you take away his narrative function of command, take him out of his normal setting of the starship and take away all his old crew. His essential character traits and behaviours still remain – he continues to be a man of great moral integrity and high principles, he still drinks Earl Grey tea (although now the decaf version) and he still quotes Shakespeare, although not until the final episode. But the absent Enterprise and the absent crew inevitably make him a different character to the one whom we got to know through seven seasons of TNG. In the second episode, when Picard has determined to return to space in search of Bruce Maddox he tells his Romulan caretakers that he has deliberately not called on his old crew to accompany them because he knows that they would agree and that helping him would cause trouble for them. However, as mentioned above, the narrative arc of the first episode is to re-establishes his narrative function as a commander – that’s why it’s so thrilling in the final episode to see him pilot a starship for the first time in twenty years. And it gives him a new crew to replace the old. So, it could be argued that the show presents a character who is not Picard, or not Picard as we have known him, at the beginning and by the end restores the character to the one that we do know. But we should remember to discuss the fact that some fans think that the synth Picard is not really Picard.

Speaking of characters, we do have to mention all those returning characters who show up presumably to please the fans, but then get killed. You’ve got Maddox (John Ales), who is killed by Agnes Jurati (Alison Pill), Seven’s adopted son Icheb (Casey King), and Hugh (Jonathan Del Arco). It’s like a slaughter of the backstory characters.

Baker

It’s not just that Seven’s adopted son Icheb dies. Christian Blauvelt, writing for IndieWire, argues that the drilling of Icheb’s eye socket is “probably the most brutal moment ever in any incarnations of ‘Star Trek’”, and suggests it underscores Seven’s transformation into gritty, traumatised vigilante. It’s such a visceral, confronting scene.

More broadly, Variety argues Picard “is different from its predecessor in nearly every respect – texture, tone, format, production value, even the likelihood of characters dropping an f-bomb”. People’s responses to that shift in tone have been pretty varied. Fan Tina C. writes, “The violent, dark, dystopian, vulgar hellscape they’ve supplanted is not Star Trek”.

This is part of a bigger shift, though. As Andrew Lynch and Alexa Scarlata point out in a forthcoming chapter in Science Fiction Television and the Politics of Space, adult science fiction on subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) services is shifting the genre into grittier terrain than their broadcast equivalents, including the Star Trek franchise. Bryan Fuller, creator of Star Trek: Discovery, acknowledges there’s a tricky balance to be achieved between the more adult content possible on CBS All Access and the desire to maintain Star Trek’s “younger viewers”.

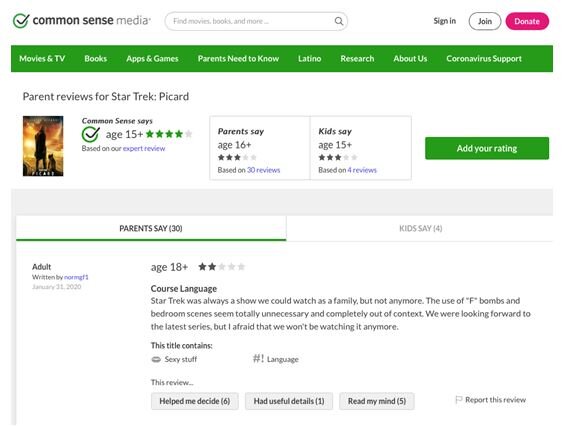

If we look at parental advisory sites such as Common Sense Media, the parental backlash to both Discovery and Picard suggests many feel that balance has not been achieved: “Now I can't even watch it with my kids… Wish they would had kept it family friendly”. These are adults who want to bring children into the world of Star Trek by watching it with them together as a family. It’s worth noting that for the most part these are parents who enjoy Picard themselves, but lament the shift of the franchise from family to older teen/adult viewing. For others, a Star Trek that is not family friendly is “not Star Trek” at all.

In my Star Trek book, I’ve written about how TOS was initially misconstrued (and summarily dismissed) as a children’s program when it first aired, primarily because serious science fiction television was associated with drama anthologies, while the cheap space operas of the 1950s had been pitched at children. It was only in its final season that reviewers were engaging with Star Trek as serious intergenerational fare that dealt with contemporary social issues in science fiction guise. TNG more deliberately targeted the family audience by making the Enterprise a family spaceship, to the notable discomfort of Picard, and through the inclusion of young Wesley Crusher (Wil Wheaton).

While Picard’s showrunner Michael Chabon has defended the dark turn of Picard by saying Star Trek always reflects the time in which it is made, it is worth remembering the significant cultural unrest in the 1960s when TOS aired. As such, Stephen Kelly argues that “the idea that the grittiness of shows such as Picard makes it mature and relevant, while the ethos of yesteryear Star Trek is now naive or too old-fashioned to survive, feels misjudged. The hope, optimism and sincerity of the original 60s series was in itself a radical act”.

All the same, by the end of season one, Picard brings a peaceful resolution by affirming the values that the Federation appears to have abandoned, and Riker seems to bring Starfleet to its senses in backing Picard.

Chabon suggests “the space we found for Picard is not ‘dark Federation’” – which makes me think of Blake’s 7 (1978-1981) – “It’s one of people who live and work at or beyond the margins of the Federation who travel beyond its boundaries”. But is it also beyond the boundaries of family fare? Certainly, I was disappointed in this regard.

Pearson

When the Science Museum in London had a Star Trek exhibition back in 1995, Máire Messenger Davies and I distributed a questionnaire to visitors asking why they were visiting. There were grandparents bringing their grandchildren in order to introduce them to the franchise. So, this comes back to what audiences CBS is targeting, is it the old audience or the new audience? That could be seen as a failure in both Picard and Discovery, because what you want to do is precisely to cultivate an intergenerational loyalty – think of Disney, or Star Wars – they want it to be passed down the generations, and yet if you put in either too much sexual or violent content, that’s hard to do.

Baker

If you want a franchise to survive over decades and generations, you have to repopulate that fan base.

Pearson

However, what CBS is intending to do as a franchising strategy is having a range of programs for different demographics, with an animated series aimed at a younger audience. Increasingly with transmedia products within a franchise, they’re trying to target different audiences with different content. This seems to be what CBS is now going to do with Star Trek and wanting to proliferate the number of series they’re producing.

Baker

The kickback some of the fans who are parents or grandparents is that they don’t necessarily want their kids watching a separate Star Trek, and I feel that way too. I want new Star Trek we can watch together and then chew the fat together afterwards as well.

Pearson

That speaks to what is television, in that television became increasingly fragmented with the proliferation of cable and then the streaming services which clearly target multiple niche audiences. Netflix does have family versions of horror and science fiction to watch together, so it’s trying to address that audience.

Baker

Yes, one of my current research projects, with Jessica Balanzategui and Diana Sandars, looks at the darker science fiction, fantasy, and horror content on Netflix that’s nonetheless pitched at a family audience under the genre tag “Family Watch Together TV”. It’s still a really controversial strategy because trying to get that balance right between something that’s edgy enough for adults to enjoy but not so creepy that your youngest child can’t sleep at night is really tricky. For example, the Lost in Space (2018-) remake and The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance (2019 -) both come under that umbrella on Netflix and are rated TV-PG in the United States. Of course, when those shows come up on a parent’s feed, it will often be sitting next to a creepier show at a higher classification, so you may well click there next into even darker content.

Pearson

When I think of family science fiction viewing here in the UK, I think of the reinvented Doctor Who (1963-1989, 2005-), which was designed precisely for that intergenerational audience. It was broadcast in the early evening when children would be able to watch with the family. I remember there were complaints about content that wasn’t suitable for children in Doctor Who because it was very much marketed by the BBC as family viewing.

Going back to the pandemic, which inevitably we must these days, I was reading in The Guardian how the viewing of terrestrial, broadcast television has really increased during the COVID-19 crisis, because people want to watch TV together, they want comforting television. There’s a show over here called The Repair Shop (2017-) about repairing old items which is now apparently a big hit because everybody’s watching it together.

Baker

It comes back to the old-fashioned water-cooler TV, so you can watch things together and discuss them at the same time, in the same week. As much as we’ve said that Picard is very much informed by the new Netflix-era streaming era, it was still released on that week-by-week drip feed, to try to reinstate that water-cooler moment, so you felt that if you wanted to be in that conversation, you had to be watching it at the same time.

Pearson

That’s very interesting in terms of the strategy – whether you drop all the episodes at once or you space them out as in the broadcast era. I find myself getting frustrated because I know they’ve got all the episodes, so why aren’t they giving them to me? Why do I have to wait?

Baker

We’ve become newly enculturated to watching episodes back-to-back in one or more “epic viewing” sessions, as I call it in The Age of Netflix. Our expectations have changed.

Pearson

On the other hand, what are the pleasures of television? The pleasure of the weekly drop is that you have more time to contemplate, you do have time to get caught up in that ongoing conversation. After both Discovery and Picard, I would read all the recaps, I would look to see what the fans were saying, and I found that very helpful because the storytelling is so intense that I think you need the collective intelligence to help you figure out what the hell is going on and what you might feel about it.

Baker

I find that very interesting, because it’s an amplification of what was around even in the 1950s with early television, when they did some studies that said prediction and anticipation were key pleasures of TV watching, particularly with serialised stories. It’s talking to other people before the next episode drops which is part of the fun. So even though we're in a new era, doing the weekly drop is re-instigating something that’s been there since the very beginning of TV, that pleasure/pain of anticipation, making you wait.

Pearson

Yet I also want to know what’s going to happen, so I want to binge. With Better Call Saul (2015-), I decided I would wait until all the episodes dropped before watching.

Baker

Everyone’s got so used to that way of viewing, that it’s too frustrating to watch it bit by bit.

Pearson

But after binging Better Call Saul I don’t know if I will have the energy to then read recaps and reviews the way that I would if I had watched week by week. So, it’s a question of which pleasure you prioritise. Do you want the time to reflect and read and talk to other people, or do you want it all at once?

Baker

Then that has flow on effects, because if you’re waiting, there are certain places online you can’t go.

Pearson

Exactly, this came up with my Facebook feeds around Picard. I hadn’t watched the final episode of Picard, because it dropped just as we went into lockdown. I had a friend coming over every week and we were cooking dinner and watching the weekly episode of Picard together, and then occasionally we FaceTimed with her sister in Israel to discuss it afterwards. We were very much treating it as appointment television.

When the final episode dropped in lockdown, I really didn’t want to watch it without my friend coming over. It became symbolic of all the things we were losing in our lives. Then another friend said I might not want to watch it if I was feeling delicate. I was feeling very delicate at that point! So, I waited for a long time. That meant I would just have to very quickly scroll past everything in my Facebook feed that related to the finale, because I hadn’t seen it yet. But you can’t avoid reading the headlines!

Negotiating television is much harder than it used to be in terms of viewing practices and preferences because of choices about binging or watching individual episodes as well as decisions about which streaming services you want to subscribe to. CBS All Access used both Discovery and Picard to drive subscriptions in the United States, successfully it seems. Internationally the shows appeared on Netflix and Amazon. I signed up for both platforms because I had to watch new Trek shows.

Baker

Some of my friends who are also Star Trek fans thought they had too many subscriptions already and were waiting for all the episodes of Picard to drop, so they could watch the entire season in a free trial period.

Pearson

Will the next step be bundled streaming packages?

Baker

At this stage that seems inevitable, unless some of the providers fold before then. When there are TV shows that everyone’s talking about and you’re supposed to be watching them, but they’re all on different providers, it’s just unsustainable.

Pearson

Even if their price point is low, if you have several subscriptions it's going to add up over the course of a year. It points to the importance of the flagship program that attracts new subscribers to streaming services.

Baker

I probably did what Amazon wanted me to, which is that I signed up specifically for Picard, and then I found The Marvellous Mrs. Maisel (2017-) and The Man in the High Castle (2015-2019). The industry logic is that you have these flagship shows, and then ideally, it’s the rest of the catalogue that keeps you there.

Pearson

I think that’s true, but they have to have enough in the catalogue to keep you in there. Mrs. Maisel, The Man in the High Castle, also Transparent (2014-2019), these were the shows that were getting the buzz, and I felt out of the conversation around those shows so like you started to watch or plan to watch them.

Here in the UK, Discovery is on Netflix, but Picard is on Amazon. Why might CBS’s international division make that call? There’s so much to research around this from both an industry and an audience perspective.

And now content will start to dry up with the impact of COVID-19 on the industry. I presume production on Picard season two has now been delayed. Will the streamers be able to turn out enough new flagship shows to drive subscriptions and then maintain those viewers?

Baker

There will come a point when no new content is coming through, and those streaming services with the stronger catalogue will be in a better position to survive.

Thinking about Picard season two, we really need to discuss that finale. Picard is now both an XB like Seven and a synth like Soji (Isa Briones), but without her additional longevity and non-human capabilities because apparently – as fan Legate Damar argues – “anybody who knows Picard knows that Picard wouldn’t want any of that”.

Pearson

What’s the average life span of a human in the twenty-fourth century? Having gone through all that, wouldn’t he want a younger body and more time? I’d be perfectly happy to adjust to a new body!

Baker

I had to go and look it up. In the TNG pilot, Doctor McCoy (DeForest Kelley) is 137, which would potentially give the 94-year-old Picard another 43 years without his neural condition. On the other hand, that doesn’t mean McCoy’s longevity is the ‘average’, and he’s pretty frail.

Pearson

And Picard asks, “Ten years? Twenty years?” So, he does want at least some more time.

A related question is if they could download Picard, why couldn’t they download Data (Brent Spiner)?

Picard wakes in his synthetic body

Baker

I had to watch it again to see if I could figure that out, and even then, I had to go online and see whether anyone had a reasonable explanation. According to Chabon, the idea is that this Data is an incomplete “simulated reconstruction”.

Pearson

There’s also a practical problem, in that 71-year-old Brent Spiner said ages ago that he couldn’t keep playing Data because he’s ageing, and an android isn’t supposed to age. In Picard, you see the real Spiner in the character of Dr Altan Inigo Soong and then you compare him with Data, and you can see the make-up and post-production work and lighting to make those scenes work.

Baker

As well as the publicity photos, where you can see him in make-up but before the CGI.

Brent Spiner and Patrick Stewart relax between takes

Pearson

I found the idea that one positronic neuron from Data could be used to make Soji and Dahj quite implausible. That being said, I bought Data as the same character as he had been in TNG. The speech patterns were the same, the facial expressions were the same. To see Picard and Data together even in the dream sequences was very emotionally resonant.

If we’re thinking about the primary arc of the season being Picard’s redemption and resurrection, it’s not only that he feels he has to redeem himself with regard to the Romulans, it’s also because of his guilt over Data’s sacrificing himself for Picard in Nemesis. Picard is able to come to terms with his guilt by having a chance to say goodbye to Data. Data then becomes an important element of Picard’s narrative arc.

Baker

I thought the dream sequences were beautiful, partly because we see Picard’s regret over Data’s sacrifice.

Pearson

I loved the dream sequences, especially the first one in which the two play poker, since that harks back to TNG. Although have to say that fans thought that Data’s holding five queens in his hand would become an important plot point and it didn’t.

Deceased Picard and Data

Baker

I feel sorry for Data, though, in that it’s unclear whether he’s been experiencing the real passage of time, on his own, in a grey room. It seems like a sad place for him to have been after making that sacrifice. No wonder he wants it to end.

Pearson

The scene where they terminate him is very touching, and it does give Picard a chance to quote Shakespeare again.

Baker

This brings us to whether the synth Picard who farewells Data is still really Picard. As fan SilenceKit puts it, this raging philosophical “debate is the point”. By not resolving the existential issues around Picard II, the finale leaves an open space for everyone to talk about it between the seasons before they are (hopefully) unpacked when the series returns.

If he’s quoting Shakespeare and making speeches, that seems pretty Picard!

Pearson

Absolutely! That comes back to my theory of character. I'd be inclined to argue it is Picard. He’s got all his memories, he’s quoting Shakespeare, he looks and sounds like Picard. He’s doing all the things Picard should do.

The interesting thing in the second season will be if he has glitches, if there are things he doesn’t remember, or if he behaves uncharacteristically.

Baker

Although I wonder if that will make season two a little too like Dr Hugh Culber (Wilson Cruz) over on Discovery (albeit in a different context and without ‘killing your gays’ along the way)? We have two cases of a character coming to terms with being in a new body.

Pearson

At the beginning of the season, Picard gets the news about the abnormality from Dr Moritz Benayoun (David Paymer), who served with him on the Stargazer, which was a nice touch. But we knew that Picard wasn’t going to die because by the time the first season dropped, the second season had been greenlit. As soon as it becomes clear that the season is centred around synths, that’s the obvious solution. The downloading into the synth body comes as no surprise. There’s also preparation for this in his discussions with Dahj in which he reassures her that she is indeed as real as he is. So, Picard himself will probably believe that he is the real Picard.

Baker

It poses a potential Altered Carbon (2018-) scenario. They've strategically made the new Picard mortal, but if knowledge of this technology goes public, anyone without those moral qualms will want to download themselves and live forever.

Pearson

My assumption is that there’s only one synth prototype. Picard says to Soong that he’s sorry to have taken the synth body that Soong had intended for himself. But if there was a successful prototype, they could roll it out.

Baker

I felt there was an inference that Maddox may have been needed, but it wasn’t clear.

There are some practical plot holes in the finale but also some incomplete philosophical issues that are raised. I hope that they don’t drop the ball on all of those in season two, that they actually do something with them.

Pearson

Beyond those first two episodes, which introduce the Picard character, I was as confused as anybody else as to the overall plot.

Wherever it goes, Star Trek always needs to reinvent itself for each new period of TV. It gets reinvented not just in industrial terms but also in ideological terms because it has to reflect the time in which it’s being produced.

If people say Picard isn’t Star Trek, what do they want? Do they want every new series simply to replicate TOS? Does it have to be Gene Roddenberry’s vision of the universe? As I point out in our book, writers like Ron Moore were contesting Roddenberry’s view of the Star Trek universe in terms of the lack of conflict among characters because they found it too constraining. You can’t preserve Trek in amber.

Baker

It brings us back to nostalgia. There’s a pleasure in returning to our favourites, but deep down we all know that it has to move to on, for cultural reasons, for industry reasons. People won’t watch it in if it’s an exact replica. They might think they will, but TV has simply changed too much over the years.

Pearson

A franchise can’t survive on just the core fan base. It has to pull in other viewers.

Djoymi Baker is Lecturer in Cinema Studies at RMIT University, Australia. With a background in the television industry, she writes on topics such as streaming, genre studies, fandom, and myth in popular culture. Djoymi is the author of To Boldly Go: Marketing the Myth of Star Trek (2018) and the co-author of The Encyclopedia of Epic Films (2014). Her current research examines children’s television and intergenerational spectatorship.

Roberta Pearson is Professor of Film and Television Studies at the University of Nottingham, UK. She is the co-author of Star Trek and American Television (2014), editor of Reading Lost: Perspectives on a hit television show (2009) and the co-editor of several titles including Storytelling in the Media Convergence Age: Exploring Screen Narratives (2015), A Critical Dictionary of Film and Television Theory (2014) and Cult Television (2004).