Last time, I shared the revised syllabus for my PhD Seminar on Fandom, Participatory Culture and Web 2.0. Today, I want to share my up-dated syllabus on Transmedia Entertainment. Here, the changes are less dramatic; there has been an explosion of new writing about transmedia among academics and I have incorporated state of the art research into the course readings. But there is nothing as dramatic as a paradigm shift on the level of the debates around race and nationality in fandom we discussed last time.

The core framework has changed very little since the last time I taught the class three years ago, even if the selection of cases and readings has shifted some. I take advantage of our Los Angeles location to bring an interesting mix of speakers to the class, people who are out there doing ground-breaking work and can introduce a grounded perspective to my students. Most of the students who take this class are from the Cinema School, many of them want to break into the mainstream entertainment industry, and the course has developed a reputation as one which helps them to understanding the big picture of how Hollywood is functioning right now.

That said, it is far from clear how much longer the transmedia term will operate in its current form. Academic institutions have embraced it even as it has more and more fallen from use in the entertainment industry. As one of my guest speakers said in our first class session, “there is no transmedia industry; there is only the entertainment industry.” Transmedia perspectives are everywhere and nowhere when we look at what’s happening at, say, Disney+ and the D23 conference a few weeks ago. At the same time, I am starting to see faculty teaching Trans Media classes, which focus on programs like Pose or Orange is the New Black or any number of independent films which take up transgender perspectives. So it isn’t just that the term has lost its meaning in the industry but it is also developing competing meanings within the academy. Something is going to have to give. But for now, here’s what I am teaching this term.

CTCS 482: Transmedia Entertainment

Fall 2017

Tuesdays 2:00-5:50pm

SCA 316

4 units

Contact Information:

Henry Jenkins

Office: ASC 101C

hjenkins@usc.edu

TA: Jesse Tollison

Please send all inquiries regarding office hour appointments to Jocelyn Kelvin and questions regarding the course to Professor Jenkins or Jesse Tollison.

TRANSMEDIA ENTERTAINMENT

We now live in a moment where every story, image, brand, and relationship plays itself out across the maximum number of media platforms, shaped top down by decisions made in corporate boardrooms and bottom up by decisions made in teenagers’ bedrooms. The concentrated ownership of media conglomerates increases the desirability of properties that can exploit “synergies” among different parts of the medium system and “maximize touchpoints” with different niches of audiences. The result has been a push toward franchise-building in general and transmedia entertainment in particular.

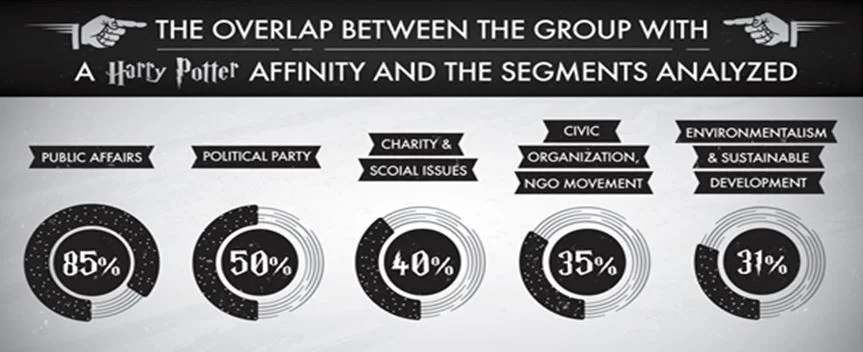

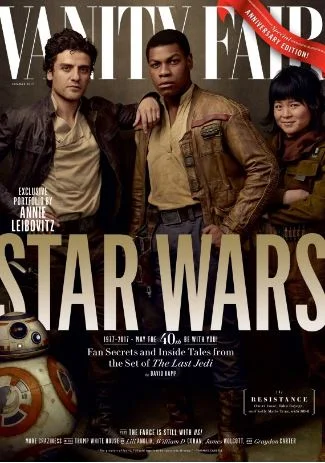

A transmedia story represents the integration of entertainment experiences across a range of media platforms. Franchises, such as The Walking Dead, Game of Thrones, The Marvel Cinematic Universe, Harry Potter or Riverdale move fluidly across media platforms (television, film, comics, games, the web, even alternate or virtual reality) picking up new audiences as they go and allowing the most dedicated fans to drill deeper. The fans, in turn, may translate their interests in the franchise into concordances and Wikipedia entries, fan fiction, vids, fan films, cosplay, game mods, and a range of other participatory practices that further extend the story world in new directions. Both the commercial and grassroots expansion of narrative universes contribute to a new mode of storytelling, one which is based on an encyclopedic expanse of information which gets put together differently by each individual, as well as processed collectively by social networks and online knowledge communities.

Each class session will introduce a concept central to our understanding of transmedia entertainment that we will explore through a combination of lectures, screenings, and conversations with industry insiders who are applying these concepts through their own creative practices.

In order to fully understand how transmedia entertainment works, students will be expected to immerse themselves in at least one major media franchise for the duration of the term. You should experience as many different instantiations (official and unofficial) of this franchise as you can and try to get an understanding of what each part contributes to the series as a whole.

REQUIRED BOOKS

§ Andrea Phillips, A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012)

§ Matthew Freeman and Renira Rampazzo Gambarato (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Transmedia Studies (London: Routledge, 2019) (This book is expensive so recommend renting a digital copy at https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-to-Transmedia-Studies-1st-Edition/Freeman-Gambarato/p/book/9781138483439)

§ Ann M. Pendelton-Jullian and John Seely Brown, World Building

§ For the color version: $23.00 - http://www.lulu.com/shop/ann-pendleton-jullian/world-building/paperback/product-23934846.html

§ For the black and white version: $7.00 - http://www.lulu.com/shop/ann-pendleton-jullian/world-building/paperback/product-23934845.html

All additional readings will be provided through the Blackboard site for the class.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL RESPONSE

For the first assignment, you are asked to write a 5-7 page autobiographical essay describing your relationship to a media franchise that you have found to be personally meaningful. You should use this essay to identify the cultural attractors that drew you to this franchise, to discuss which variants of the franchise you experienced, and to describe any cultural activators that encouraged you to more actively contribute to the fan community surrounding this franchise. Be as specific as possible in discussing moments in the transmedia story that were especially important in shaping your engagement with the property. Make explicit reference to ideas about transmedia and engagement from the readings. This assignment is partially about getting to know you as a transmedia participant and partially about getting you to experiment with the critical vocabulary we’ve introduced so far for talking about transmedia experiences. (Due September 10) (10 Percent)

EXTENSION PAPER

Write a 5-7-page essay examining one commercially produced story (comic, website, game, mobisode, amusement park attraction, etc.) that acts as an extension of a “core” text (for instance, a television series, film, etc.). You should try to address such issues as its relationship to the story world, its strategies for expanding the narrative, its deployment of the distinctive properties of its platform, its targeted audience, and its cultural attractors/activators. The paper will be evaluated on its demonstrated grasp of core concepts from the class, its original research, and its analysis of how the artifact relates to specific trends impacting the entertainment industry. Where possible, link your analysis to the course materials, including readings, lecture notes, and speaker comments. (30 Percent, October 29)

FINAL PROJECT – FRANCHISE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT

Students will be organized into teams, which—for the purpose of this exercise—will function as transmedia companies. You should select a media property (a film, television series, comic book, novel, etc.) that you feel has the potential to become a successful transmedia franchise. In most cases, you will be looking for a property that has not yet added media extensions, though you could also look at a property that you feel has been mishandled in the past. You should have identified and agreed on a property no later than Sept. 12th. [j2] Each week, a designated member from each team should email a brief summary of your progress to Professor Jenkins and Jesse Tollison. Ideally the report will reflect your thinking around that week’s focus.

By the end of the term, your team will be “pitching” this property. The pitch should include a briefing book that describes:

1. the defining properties of the media property

2. a description of the intended audience(s) and what we know of its potential interests

3. a discussion of the specific plans for each media platform you are going to deploy

4. an overall description for how you will seek to integrate the different media platforms to create a coherent world

5. parallel examples of other properties which have deployed the strategies being described

For a potential model for what such a book might look like, see the transmedia bible template from Screen Australia, available here: http://videoturundus.ee/bible.pdf

Include only those segments of their bible template that make sense for your particular property and approach. You can also get insights on what a bible format might look like from the Andrea Phillips book.

The pitch itself will be a group presentation, followed by questions from our panel of judges (who will be drawn from across the entertainment industry). The length and format of the presentation will be announced as the term progresses to reflect the number of students actually involved in the process and thus the number of participating teams. The presentation should give us a “taste” of what the property is like, as well as lay out some of the key elements that are identified in the briefing book. Each team will need to determine what the most salient features to cover in their pitches are, as well as what information they want to hold in reserve to address the judge’s questions. Each team member will be expected to develop expertise around a specific media platform, as well as to contribute to the overall strategies for spreading the property across media systems.

The group will select its own team leader, who will be responsible for contact with the instructor/TA and who will coordinate the presentation. The team leader will be asked to provide feedback on what each team member contributed to the effort, while team members will be asked to provide an evaluation of how the team leader performed. Team members will check in on Week Six, Week Ten and Week Thirteen to review their progress on the assignment.

Students will pitch their ideas to the panel of judges on December 3. They should expect to receive feedback from the instructor over the following few days, and then turn in the final version of their written documentation on the exam date scheduled for the class. (40 percent)

CLASS FORUM/PARTICIPATION

For each class session, students will be asked to contribute a substantive question or comment via the class forum on Blackboard. Comments should reflect an understanding of the readings for that day, as well as an attempt to formulate an issue that we can explore with visiting speakers. Students will also be evaluated based on regular attendance and class participation. (20 Percent)

WEEK ONE:

Tuesday, August 27

Transmedia Storytelling 101

§ Henry Jenkins, “Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling,” in Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), pp. 93-130.

§ Henry Jenkins, “Transmedia Storytelling 202: Further Reflections,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, August 1, 2011, http://henryjenkins.org/2011/08/defining_transmedia_further_re.html

§ Elizabeth Evans, “Transmedia Texts: Defining Transmedia Storytelling,” in Transmedia Television: Audiences, New Media, and Daily Life (London: Routledge, 2011), pp. 19-39

§ Andrea Phillips, “What’s Happened to Transmedia?” Immerse https://immerse.news/whats-happened-to-transmedia-855f180980e3

§ Henry Jenkins, “Transmedia What?” Immerse https://immerse.news/transmedia-what-15edf6b61daa

§ Christy Dena, “Transmedia Performing Badly,” Immerse https://immerse.news/transmedias-transitions-9c28ef2c5835

§ Caitlin Burn, “Transmedia: Art Forms Created in Real Time,” Immerse https://immerse.news/transmedia-art-forms-created-in-real-time-4943648389a4

Guest Speaker: Mike Monello is a true pioneer when it comes to immersive storytelling and innovative marketing. In the late 1990s, Monello and his partners at Haxan Films created The Blair Witch Project, a story told across the burgeoning internet, a sci-fi channel pseudo-documentary, books, comics, games, and a feature film, which became a pop-culture touchstone and inspired legions of “found-footage” movies in its wake. It forever changed how fans engage with story and how marketers approach the internet. Inspired by the possibilities for engaging connected fan cultures and communities online, Monello co-founded Campfire in 2006. There, he leads an agency that has developed and created groundbreaking participatory stories and experiences for HBO, Amazon, Netflix, Cinemax, Discovery, National Geographic, Harley- Davidson, Infiniti, and more. Campfire won Small Agency Campaign of the Year via AdAge in 2013 and Small Agency of the Year via Online Marketing Media and Advertising Awards in 2012, and has been awarded top honors at the Emmys, Cannes Lions Festival, Clios, One Show, and MIXX. Monello serves on the Peabody Awards Board of Jurors, and regularly speaks at high-profile events such as Cannes, Advertising Week, SXSW, and more.

WEEK TWO:

Tuesday, September 3

A Brief History of Transmedia

§ Matthew Freeman, “A World of Disney: Building a Transmedia Storyworld for Mickey and His Friends,” in Marta Boni (ed.) Worldbuilding: Transmedia, Fans, Industries (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017)

§ Justin Wyatt, “Critical Redefinition: The Concept of High Concept,” in High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1994), pp. 1-22.

§ Jonathan Gray, “Learning to Use the Force: Star Wars Toys and Their Films,” in Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: NYU Press, 2010), pp. 177-187.

Team Focus: Identifying Your Property

Guest Speaker: Mark Bartscher is Senior Manager, Games & Interactive, Disney DTCI, Product & Design. He is a digital strategist and executive producer with over 15 years experience developing innovative kids content and products for new media. Working at the cross-section of technology, kids, and storytelling, his passion is to create new ways for kids to engage with the characters and stories they love. His specialties are digital strategy, product development, business development, interactive television, and game design.

WEEK THREE:

Tuesday, September 10

Producing Transmedia

§ Derek Johnson, “Battleworlds: The Management of Multiplicity in Media Industries,” in Marta Boni (ed.) Worldbuilding: Transmedia, Fans, Industries (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017).

§ Brian Clark, “Transmedia Business Models,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, November 7, 2011 http://henryjenkins.org/2011/11/installment_1_transmedia_busin.html, http://henryjenkins.org/2011/11/brian_clarke_on_transmedia_bus.html,

http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2011/11/brian_clark_on_transmedia_busi.html

http://henryjenkins.org/2011/11/brian_clarke_on_transmedia_bus_1.html

http://henryjenkins.org/2011/11/brian_clark_on_transmedia_busi_1.html

§ Andrea Phillips, “How to Fund Production Costs,” “And Maybe Make Some Profit, Too,” in A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 223-239.

§ Jeff Gomez, “Transmedia Developer: Success at Multiplatform Narrative Requires a Journey to the Heart of the Story” and Peter von Stackelberg, “Transmedia Franchising: Driving Factors, Storyworld Development and Creative Process” in Routledge Companion

Team Goal: Finalize property selection

Guest Speaker: Maureen McHugh’s most recent collection of short stories, After the Apocalypse, was one of Publishers Weekly’s Ten Best Books of 2011. She has been working in interactive storytelling since 2003 when she was a writer and managing editor for the ARG ilovebees. She worked on several major interactive projects including Year Zero for Nine Inch Nails. She’s written interactive narrative for second screen and VR. She teaches screenwriting and interactive writing at USC.

WEEK FOUR:

Tuesday, September 17

Media Mix

§ Otsuka Eiji, “World and Variation: The Reproduction and Consumption of Narrative,” in Mechademia 5, 2010, pp. 99-116.

§ Ian Condry, “Characters and Worlds as Creative Platforms,” in The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013).

§ Mizuko Ito, “Gender Dynamics of the Japanese Media Mix,” in Yasmin B. Kafai, Carrie Heeter, Jill Denner, and Jennifer Y. Sun (eds.), Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), pp. 97-110.

§ Mia Consalvo, “Convergence and Globalization in the Japanese Videogame Industry,” in Cinema Journal, Spring 2009, pp.135-141.

Team Goal: Discuss business model

Guest Speakers: Professor Cristina Mejia Visperas examines the intersections of race, state violence, and the life sciences, and whose work is deeply engaged in Visual Culture Studies, Science and Technology Studies, African American Studies, and Disability Studies. She is currently writing a book manuscript on the visual culture of postwar medical science research conducted in prisons.

Prof. Visperas holds a Ph.D. in Communication, Science Studies, from the University of California, San Diego, where she previously taught courses on communication, race, and science and technology, and during which time she was also managing editor of the open-access journal, Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience (2014-2016). Prior to becoming a communication scholar, Prof. Visperas had been a laboratory researcher in both academic and industry settings, where the focus of her work had ranged from stems cells and parasitic plants to burn injuries and the biochemistry of membranes.

Hye Jin Lee is a clinical assistant professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Lee is also the founder and former editor of Books Aren’t Dead, which is a podcast series for Fembot (fembotcollective.org) that reviews and discusses recent publications by feminist scholars in the field of media, communication, science and technology. Lee holds a Ph.D. in Mass Communication from University of Iowa. At University of Iowa, Lee served as the managing editor of Journal of Communication Inquiry (jci), a peer-reviewed academic journal that focuses on interdisciplinary scholarship in the field of communication and cultural studies. Lee’s primary research focuses on cultural meanings of popular culture and the power struggles (as well as collaborations) between the industry and the fans in the creation of those cultural meanings. Lee’s current research include K-pop industry and global fandom, transformation of cultural meaning, status and content of popular culture when it crosses borders, convergence of social media and television and the gendering of technology.

WEEK FIVE:

Tuesday, September 24

Transmedia Logics: Learning, Activism, and Play

§ Meryl Alper and Becky Herr-Stephenson, “T is for Transmedia,” Joan Ganz Cooney Center and Annenberg Innovation Lab white paper. http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/t_is_for_transmedia.pdf

§ Henry Jenkins, “Transmedia Logics and Locations,” in Benjamin W. L. Derhy Kurtz and Melanie Bourdaa (eds.) The Rise of Transtexts: Challenges and Opportunities (New York: Routledge, 2016), pp.220-240.

§ Henry Jenkins, Sangita Shresthova, Liana Gamber-Thompson, and Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, "Superpowers to the People!: How Young Activists Are Tapping the Civic Imagination," in Eric Gordon and Paul Mihailidis (eds.) Civic Media: Technology/Design/Practice (Cambridge: MIT Press), pp. 295-320.

§ Donna Hancock, “Transmedia for Social Change: Evolving Approaches to Activism and Representation” and Dan Hassler-Forest, “Transmedia Politics: Star Wars and the Ideological Battlegrounds of Popular Franchises” in Routledge Companion.

Team Goal: Discuss civic imagination goals for project.

Guest Speaker: Dan Goldman is a writer, artist and activist working in graphic novels, animated TV, video games and digital media. Creator of works like critically-acclaimed works like RED LIGHT PROPERTIES, SHOOTING WAR and PRIYA’S SHAKTI, he designs works of mindful entertainment. His next graphic novel CHASING ECHOES--which follows the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors across rural Poland in search of confiscated family land--will be released in November 2019. He lives in Los Angeles where he runs the Kinjin Story Lab with his partner Liliam.

WEEK SIX:

Tuesday, October 1 (Henry – Out of Country, class taught by Jesse Tollison)

Transmedia Aesthetics

§ Victor Kaptelinin, “Affordances,” The Encyclopedia of Human Computer Interaction, https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/affordances

§ Dena, Christy. “Beyond Multimedia, Narrative and Game: The Contributions of Multimodality and Polymorphic Fictions.” New Perspectives on Narrative and Multimodality. Ruth Page (ed.). London: Routledge, 2009. 181-201.

§ Gunther Kress

o “What is a Mode?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJ2gz_OQHhI

o “What is multimodality?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nt5wPIhhDDU

o “How do people choose between modes?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvP2sN7MFVA

Team Goals: Dig deeper into media mix of property

WEEK SEVEN:

Tuesday, October 8

Transmedia Engagement

§ Christy Dena, “Emerging Participatory Culture Practices: Player-Created Tiers in Alternate Reality Games,” Convergence, February 2008, pp. 41-58.

§ Ivan Askwith, “Five Logics of Engagement,” Television 2.0: Reconceptualizing TV as an Engagement Medium, Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2007, pp. 51-150. http://cmsw.mit.edu/television-2-0-tv-as-an-engagement-medium/

§ Andrea Phillips, “The Four Creative Purposes for Transmedia Storytelling,” “Interactivity Creates Deeper Engagement,” “Uses and Misuses for User-Generated Content,” “Challenging the Audience to Act,” and “Make Your Audience a Character, Too,” in A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 41-54, 110-126, 137-148, 149-182.

§ Paul Booth, “Transmedia Fandom and Participation: The Nuances and Contours of Fannish Participation” in Routledge Companion.

Team Goal: Strategies for audience engagement

Ivan Askwith is a cultural strategist and producer, specializing in experience design for digital platforms and fan communities. He has been named one of Fast Company’s “100 Most Creative People in Business” for “knowing how to get fans more of what they want," and described by Wired as “the secret weapon” behind entertainment's biggest crowdfunding successes, where he has raised over $20,000,000 through record-breaking crowdfunding campaigns for Veronica Mars, Reading Rainbow, Super Troopers 2, Mystery Science Theater 3000 and The Aquabats.

Askwith is also an Executive Producer for Amazon's upcoming animated transmedia series Do, Re & Mi (2020), which aims to help pre-school listeners develop a lifelong passion for music. Previously, Askwith spent several years leading the Digital Media division of Lucasfilm, and several more leading the Strategy group at Big Spaceship, an award-winning digital agency. He was also a founding member of MIT's Convergence Culture Consortium (C3), where he worked with Professor. Henry Jenkins to develop a new model for understanding fan behaviors and motives when engaging with popular culture.

Rebekah McKendry is a professor at the University of Southern California in the Cinematic Arts Department. She is also an award-winning filmmaker with a strong focus in the horror and science fiction genres. She has a doctorate focused in Media Studies focused on the Horror Genre from Virginia Commonwealth University, a MA in Film Studies focused in Cult Media from City University of New York, and a second MA from Virginia Tech in Arts Education. Rebekah previously has worked as the Editor-in-chief at Blumhouse Productions and as the Director of Marketing for Fangoria Entertainment. She is also a co-host of Blumhouse’s Shock Waves Podcast and founder of the Stephanie Rothman Fellowship for Female Film Students.

WEEK EIGHT:

Tuesday, October 15

World Building Part 1

§ Henry Jenkins, “The Pleasure of Pirates and What It Tells Us about World Building in Branded Entertainment”, Confessions of an Aca-Fan, June 13, 2007 http://henryjenkins.org/2007/06/forced_simplicity_and_the_crit.html

§ John Seeley Brown and Ann Pendleton-Jullian, World-Building

Team Goal: World Building Workshop

Professor Ann Pendleton-Jullian is an architect, writer, and educator whose work explores the interchange between culture, environment, and technology.

From a first short career in astrophysics, Professor Pendleton-Jullian has come to see the world through a lens of complexity framed by principles from ecology theory. This, in tandem with a belief that design has the power to take on the complex challenges associated with an emergent highly networked global culture has led her to work on architecture projects that range in scale and scope from things to systems of action - from a house for the astronomer Carl Sagan, to a seven village ecosystem for craft-based tourism in Guizhou province, China - and in domains outside of architecture including patient centered health, new innovation models for K-12 and higher ed, and human and economic development in marginalized populations.

Prior to the Knowlton School she was a tenured professor at MIT for fourteen years. She is also a core member of a cross-disciplinary network of global leaders established by the Secretary of Defense to examine questions of emerging interest.

As a writer, she has most recently finished a manuscript Design Unbound, with co-author John Seely Brown, that presents a new tool set for designing within complex systems and on complex problems endemic to the 21st century. Worldbuilding is one of the most powerful tools within that tool set and has been used in various diverse real world settings, as she will discuss.

WEEK NINE:

Tuesday October 22

World Building Part 2

§ Geoffrey Long, “Creating Worlds into Which to Play: Using Transmedia Aesthetics to Grow Stories into Storyworlds,” in Benjamin W.L. Derhy Kurtz and Mélanie Bourdaa (Eds.) Rise of the Transtexts: Challenges and Opportunities (New York: Routledge, 2016), pp.139-152.

§ Henry Jenkins, “‘All Over the Map’: Building (and Rebuilding) Oz,” Film and Media Studies: Scientific Journal of Sapientia University, 9, 2014, 7-29.

§ Henry Jenkins, “Matter, Dark Matter, Doesn’t Matter’: An Interview with Lost in Oz’s Bureau of Magic

§ Mark J. P. Wolf, “Transmedia World-Building: History, Conception, and Construction” in Routledge Companion.

Team Goal: Focus on World-Building

Guest Speaker: Danny Bilson is a writer, producer, director and game designer. He is currently Chair of the Interactive Media and Games Division of the School of Cinematic Arts and Director of USC Games. In Television, Bilson created and Executive Produced The Flash, The Human Target, The Sentinel and Viper. He wrote Disney’s The Rocketeer as well as the upcoming Spike Lee Joint Da 5 Bloods, to be released in 2020. As a senior executive in the game industry Bilson shepherded the Harry Potter, James Bond and Medal of Honor Franchises for Electronic Arts, as well as Saint’s Row, Space Marine, and Red Faction at THQ. He was also a producer on the original “The Sims”, helping to launch that multi-billion dollar franchise. Danny also contributed designs, concepts, and helped prototype Disney’s Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge. Danny Bilson has experience developing properties in film, video games, television, theme parks and comic books. www.dannybilson.com.

WEEK TEN:

Tuesday, October 29

Immersion and Extractability

§ Henry Jenkins, “He-Man and Masters of Transmedia,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, May 21, 2010, http://henryjenkins.org/2010/05/he-man_and_the_masters_of_tran.html

§ Henry Jenkins, “Harry Potter: The Exhibition, or What Location Entertainment Adds to a Transmedia Franchise,” Confessions of an Aca-Fan, December 14 2009. http://henryjenkins.org/2009/12/harry_potter_the_exhibition_or.html

§ Mark J. P. Wolf, “Immersion, Absorption and Saturation,” in Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (New York: Routledge, 2012), pp.48-51.

§ Andrea Phillips, “Bringing Your Story Into the Real World,” in A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 209-222.

§ Matthew Freeman, “Transmedia Attractions: The Case of Warner Bros. Studio Tour -- The Making of Harry Potter” and Anne Kerchy, “Transmedia Commodification: Disneyfication, Magical Objects and Beauty and the Beast,” in Routledge Companion

Team Goal: Merch strategies

Guest Speaker: Ivan Lopez is the General Manager of Accelerators for Techstars across the Americas West region. He has over 25 years of global executive leadership experience in business development, marketing and technology. Ivan led teams in mobile technology, fiber optics, cloud services, e-commerce, video streaming, IP licensing, gaming, SaaS, procurement, media and entertainment in North and South America, Europe and Asia Pacific. Prior to joining Techstars Ivan built the strategic partners business for Merch by Amazon creating the largest merchandise print on demand business worldwide working with over 400 major brand partners ranging from YouTube celebrities to The Walt Disney Company In this role he also launched "Merch Collab" which established a global marketplace for fan art with brand creative approval and monetization for both fan designer and brand, a first in the industry. Equally, he advises international talent and celebrities on brand creation across multiple categories that are aligned with their values and personal mission. Ivan holds a degree in Telecommunications Engineering and has completed the Harvard Law School Program on Negotiation (PON) executive training.

WEEK ELEVEN:

Tuesday, November 5

Seriality and Complexity

§ Jason Mittell, “Transmedia Storytelling,” Complex Television http://mcpress.media-commons.org/complextelevision/transmedia-storytelling/h

§ Mark J. P. Wolf, “More Than a Story: Narrative Threads and Narrative Fabric,” in Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation (London: Routledge, 2013) pp. 198-225.

§ Andrea Phillips, “Conveying Action Across Multiple Media,” in A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 93-102.

§ Frank Kelleter, “Five Ways of Looking at Popular Seriality,” in Media of Serial Narrative (Ohio State University Press, 2017), pp.7-36.

Team Goal: Segmentation and Story Flow

Though best known as one of the Emmy Award-Winning Producer/Writers of Lost, and for creating the “The Middleman” graphic novels and television series, Javier “Javi” Grillo-Marxuach is a prolific creator of television, film, comics, essays, and trans-media content. Between 2019 and 2020, Javi will have written and produced shows as varied as The Jim Henson Company’s production of The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, and Cowboy Bebop - both for Netflix - as well as the CBS summer series Blood and Treasure, while developing his original pilot Skyborn with Bad Wolf and The Jim Henson Company for UCP. Javi is also co-host and co-creator (with fellow writer/producer/Puerto Rican, Jose Molina) of the Children of Tendu podcast, an educational series which aims to teach newcomers how to navigate the entertainment industry with decency and integrity. Javier Grillo-Marxuach was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Spanish is his native language, and his name is pronounced "HA-VEE-AIR GREE-JOE MARKS-WATCH".

WEEK TWELVE:

Tuesday, November 12

Continuity and Multiplicity

§ William Uricchio and Roberta E. Pearson, “I’m Not Fooled by That Cheap Disguise,” in Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (eds.), The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to A Superhero and His Media (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 182-213.

§ Sam Ford and Henry Jenkins, “Managing Multiplicity in Superhero Comics,” in Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (eds.), Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), pp. 303-313.

§ Shawna Kidman, “Five Lessons For New Media From the History of Comics Culture,” in International Journal of Learning and Media 3.4 (2012): 41-54.

§ William Proctor, “Transmedia Comics: Seriality, Sequentiality, and the Shifting Economics of Franchise Licensing” in Routledge Companion

Team Goal: Focus on time table

WEEK THIRTEEN:

Tuesday, November 19

Subjectivity And Performance

§ Andrea Phillips, “Online, Everything is Characterization,” in A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012), pp. 83-92.

§ Sam Ford, “WWE’s Storyworld and the Immersive Potentials of Transmedia Storytelling,” in Benjamin W.L. Derhy Kurtz and Mélanie Bourdaa (Eds.) Rise of the Transtexts: Challenges and Opportunities (New York: Routledge, 2016), pp.169-186.

§ Roberta Pearson, “Transmedia Characters: Additionality and Cohesion in Transfictional Heroes” in Routledge Companion

§ Matthew Weise and Henry Jenkins, “Short Controlled Bursts: Affect and Aliens,” in Cinema Journal, Spring 2009, pp.111-116.

WEEK FOURTEEN:

Tuesday, November 26 - Teams work on Final Presentations

WEEK FIFTEEN:

Tuesday, December 3 (LAST DAY OF CLASS) - Final Presentations