Squee From the Margins: Interview with Rukmini Pande (Part II)

/I suspect some fans are going to be more willing to accept the idea of more diverse participants in fandom spaces than are going to be willing to take on an obligation to personally expand the representations of race within fandom. Can we separate out inclusion from diversity in regard to representation within a participatory culture? Why or why not?

I think the first thing to question here is the framing the concept of engaging with characters of color as “taking on an obligation.” Why should it be so?

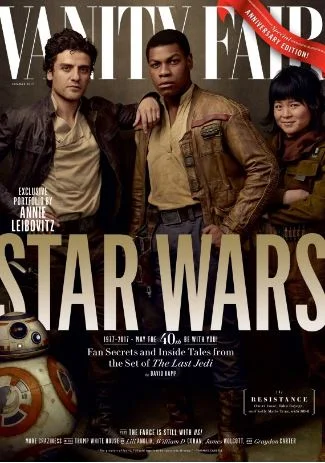

The assumption that characters of color do not offer the same possibilities of pleasure and exploration of fandom tropes and archetypes is in itself racist. Indeed, while characters of color that offer rich potential for fannish squee have always existed, as the roles offered to non-white actors within popular cultural texts have expanded this disjuncture has become even more clear. There are plenty of similarities between Bucky Barnes from the MCU movies and Finn from Star Wars in terms of their character arcs but only the former has become the locus of fan attention.

To link this to my earlier responses, there is a clear connection between the attitude that assumes that characters of color are somehow inherently unsuitable for fannish modes of pleasure and the labelling of vocal fans of color as fandom killjoys. The foreclosure of the possibility of learning to find joy in characters of color (as I did in my experiences with Star Trek) and only framing this process in punitive language – policing, obligation, scoring social justice points, etc – is in itself a product of the logic of white supremacy.

Also I think it is important to underline that fans of color have always been in these spaces and have contributed materially to their evolution through the production of fanwork, supporting projects like the AO3, and building community infrastructure. So, even though this labor has been invisibilized, I don’t think they need (or desire) the acceptance of white fans to validate their continuing participation.

One of the more chilling observations running across your book is the idea that as Hollywood has developed marginally more inclusive representations, fan fiction writing communities have tended to lag behind rather than keep pace, still focusing on white characters even when they are peripheral to the original narratives rather than helping to further develop minority characters and re-center stories around them. In what ways does the fan fiction community seem to reproduce the exclusions and silences of the entertainment industry more generally? What obligations do individual fans bear in dealing with this situation? And what strategies have emerged in response to this process of marginalization?

To pick up from my response to the last question, I think that framing these interactions in exclusively punitive terms is limiting. After all, there is a long and celebrated tradition of analyzing fandom as a learning resource. People have incessantly documented their experiences of this – from figuring out how to code, to deconstructing internalized attitudes towards sexism, homophobia, and slutshaming, to kink exploration, to researching what kind of lubricant would be available to the Victorians. However, when it comes to unlearning internalized racism – to which fans of color are equally susceptible – why is the possibility of fandom leading to that completely negated? Why do white fans need to see this engagement as an obligation or as policing? It is because there is a deep and immediate defensiveness sparked by the idea that whiteness is a racialized identity with specific effects.

To address the second part of the question, fans of color are definitely in a continual state of overt or covert negotiation with the whiteness of fandom spaces and texts and have evolved strategies to deal with it – self segregation, fanwork fests, etc. However, it is also limiting to frame their fannish activities only through this lens. It is after all, not their responsibility, nor is it within their power, to fix the problem. For instance, sometimes an angry post about how the pairing of Steve Rogers/Darcy Williams (who have never met in the MCU canon) continues to have more fanfiction than the pairing of Steve Rogers/Sam Wilson (who are well established companions) is just that – an angry post that is meant to vent frustration without offering a solution.

You argue that these silences or exclusions are not simply “glitches” in a system that otherwise works to embrace a range of identities and experiences. Rather, you see these “glitches” as part of how “fannish algorithms” operate. Explain.

In my framing, fandom algorithms are structures that are seen to order the workings of media fandom, both in terms of communitarian etiquettes and technical strategies that involve fannish digital infrastructure like archiving fanworks and organisational strategies such as tagging. These algorithms are basically “strategies of squee.” They are seen to operate independently and without bias towards any particular individual fan or character.

So when racism is seen to interrupt their workings, it is seen in the form of a “glitch,” an interruption of a system that otherwise works smoothly towards promoting such common fannish experiences such as the formation of safe spaces, the exchange squee, the pushback against a restrictive canon and the lessening of friction between opposed groups.

Another effect of this formulation is to see the roots of these glitches, when they occur, as part of a larger systemic malfunction that fandom participants cannot influence. This allows for troubling patterns of behaviour to be deflected outwards onto flawed popular cultural texts or onto individuals who act in bad faith against fandom etiquettes, allowing the core liberal nature of media fandom spaces to operate without questioning.

As an example, fandom algorithms can be axiomatic such as “Ship and Let Ship” which is seen as a basic common sense approach to fandom spaces where different individuals have different needs from a text. Theoretically, the operation of this algorithm would result in a harmonious fan space but the “glitch” would occur when fans of Finn from Star Wars would point out the anti-blackness that is influencing his sidelining in fanworks.

The larger effect of this algorithm then is to encourage fans to ignore patterns of erasure over time, such as the inevitable elevation of white characters in text after text.

__________

Dr Rukmini Pande is currently an Assistant Professor in English Literature at O.P Jindal Global University, India. She completed her PhD at the University of Western Australia. She is currently part of the editorial board of the Journal of Fandom Studies and has been published in multiple edited collections including the Wiley Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies and The Routledge Handbook of Popular Culture Tourism. She has also been published in peer reviewed journals such as Transformative Works and Cultures and The Journal for Feminist Studies. Her monograph, Squee From The Margins: Race in Fandom, was published in 2018 by the University of Iowa Press. She is also working on an edited collection on race/racism in fandom in order to bring together cutting edge scholarship from upcoming scholars in the field.