I have been using this blog to share the syllabi of the new courses I am developing for the University of Southern California -- courses which reflect my long-standing research interests.

This semester, I was asked to develop a course for the multidisciplinary iMap program in the Cinema School, a program which encourages the interplay between theory and practice. The original subject was developed by the late Anne Friedberg, so I am very much aware of her intellectual legacy as I developed my approach to this subject matter.

I also saw it as a chance to revisit some of my own intellectual roots -- with different topics hearing paying tribute to faculty who have influenced my own intellectual development, including Edward Branigan, Rick Altman, David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson, and David Thorburn -- as well as some such as Tom Gunning and George Lipsitz who have shaped my thinking from afar.

I intend to use this course both to expose students to key ideas drawn from a range of different areas of media studies and to get them to think critically about a range of different media texts. Film, no doubt, plays a special role in this class, because there is such a fully developed tradition of critical and theoretical writing there, but we will also be constantly returning to contemporary developments in digital media as a space against which to test these various theories.

For me, the formal and aesthetic dimensions of this course will form a nice contrast with the more social and ideological issues I am exploring in the Civic Media class that I shared with my blog readers earlier this summer.

Medium Specificity

This course takes as its central themes the borders and boundaries between media. Early on, we will consider some attempts to develop theories of medium specificity - trying to determine what traits define film, photography, and games with a focus on what differentiates them from other existing modes of representation. How is photography distinct from painting? What are the defining traits of the cinematic? Are games narratives? As we deal with these theories, we will show how they each moved from descriptions of the properties of specific medium to prescriptions for what the aesthetics of these media should look like. It is at this intersection where this course most clearly explores the relationship between theory and practice. Even with these medium-specific approaches, we will be exploring how their development required a mode of comparison across media. So, we see Eisenstein, for example, resting his theory of the cinematic on analogies to text-based media and Bazin drawing on notions of photography and theater to talk about cinema. And we will explore how writers like Arnheim sought to resist the coming of sound in order to protect what they saw as the "purity" of their medium specific approach.

As the course continues, we will dig more deeply into media theories and practices which consciously explore the intersections between expressive media rather than marking the borders between them. We will explore notions of interface, affordance, narrative, character, space and spectacle, globalization, and cultural hierarchy as they relate to the interplay between different media systems and practices. Here, we will be looking at theories which celebrate hybridity and border crossing rather than seeing them as problematic. Yet, in doing so, these theories still make implicit assumptions about what each medium does best or what each has to contribute to a transmedia system. So, again, we will find that the notion of medium specificity plays a central role in such formulations.

Across the course, we will be looking at a range of media texts as vehicles through which to test and expand the theories we are studying. These texts are sometimes read as experiments in medium specificity and border crossing and in other cases these works are seen as making their own conceptual contributions to our understanding of the interplay between different kinds of media. In every case, they will be looked at as illustrations of how media theory might inform creative practice and how production may help extend theoretical arguments.

Books:

David Bordwell, On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press)

Rick Altman, A Theory of Narrative (Columbia University Press)

Bryan Talbot, Alice in Sunderland (Dark Horse)

David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins (eds.), Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition (MIT Press)

Assignments:

Contributions to Class Forum on Blackboard (20 Percent) Students should share short reflections or questions on the materials read for each week's session, which can be used as a springboard for class discussions. Ideally, these should be posted by 10 a.m. on the day the class is being held.

The Specificity of Digital Media (20 Percent) Much of what we are reading this semester was written in regard to early 20th century media such as film and photography. In what ways have these debates surfaced as our culture has responded to the emergence of new media of expression? What similarities or differences do you see in terms of the debates about games or the web and the debates about these earlier media? Which ideas from the past offer us the best tools for thinking about the present and future of digital expression? (Sept. 27)

Textual Analysis Paper (20 percent) Students should select one of the media texts we have watched through the class session and develop a five page paper which explores the relationship of this work to its medium. You should draw on ideas from one or more of the essays we've read this semester to help you frame your approach. OR you should select a specific theme or creative problem (such as representing simultaniety or microcosm) which has been expressed across media. Select at least three texts representing three different media and discuss how the creative artists involved how exploited the potentials of those media to work through this challenge. (Nov. 8)

Final Paper (40 percent) - Students should write a 20 page essay on a topic of their own interests as they reflect to the core themes and concerns which have run through the class. Students may consider doing a creative project which explores these same issues with permission of the instructor. Students should submit a one to two page abstract of the project by the mid-term so that they can receive feedback as they are developing their concepts. Students will give a 10 minute final presentation sharing their project with the class.(TBD)

August 23rd

Kristin Thompson, "Take My Film, Please," Observations on Film Art

Laura Marks,"The Memory of Touch," The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema,

Embodiment and The Senses (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000).

Donald A. Norman, "Affordances, Conventions and Design," Interactions 6(3):38-43, May 1999, ACM Press.

Screening: Sita Sings the Blues (2009)

The Problem of Medium Specificity (August 30th)

Geoffrey Pingree and Lisa Gitelman, "What's New About New Media?," New Media

1740-1915 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), pp. xi-xxii.

Noel Carroll, "Medium Specificity Arguments and the Self-Consciously Invented Arts:

Film, Video, and Photography," Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1996), pp. 3-24.

D.N. Rodowick, "The Virtual Life of Film," The Virtual Life of Film (Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 2007), pp.1-24.

David Bordwell, "Defending and Defining the Seventh Art: The Standard Version of

Stylistic History," On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), pp.1-45

Rudolph Arnheim, "Television, a Prediction" and "A New Lacoon: Artistic Composites and the Talking Film," Film as Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957), pp.199-220.

Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov, 'Statement on Sound,'

The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents, 1896-1939, edited by Richard Taylor and Ian Christie (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), pp. 234-35.

Screening: Applause (1929)

LABOR DAY, NO CLASS (September 6th)

Medium Specificity in Cinema (September 13th)

David Bordwell, "Against the Seventh Art: Andre Bazin and the Dialectical Program,"

and "The Return to Modernism: Noel Burch and the Oppositional Program," On

the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), pp.46-83.

Andre Bazin, "The Ontology of the Photographic Image," Film Quarterly 13(4)

(Summer 1960), pp. 4-9.

Andre Bazin, "The Myth of Total Cinema," and "Theater and Film", What is Cinema? (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

Sergei Eisenstein, "Dickens, Griffith and the Film Today", "The Cinematic Principle and

the Ideogram," Film Form: Essays in Film Theory (New York: Harcourt Brace,

1949), pp.28-44, 195-256.

Rick Altman, 'Dickens, Griffith and Film Theory Today," in Jane Gaines (ed.), Classical

Hollywood Narrative: The Paradigm Wars (Durham: Duke University Press,

1992), pp. 9-47.

(Rec. for reading after class: Kristin Thompson, "Playtime: Comedy on the Edge of Perception," Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Trenton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

Screening: PlayTime (1967)

Medium Specificity in Photography (September 20th)

David Company, "Stillness," Photography and Cinema (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), pp. 22-59.

Jane Gaines, "Photography Surprises the Law: The Portrait of Oscar Wilde," Contested Culture: The Image, the Voice, and the Law (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992)

Robert Harriman and John Louis Lucaites, "The Borders of the Genre: Migrant Mother

and the Times Square Kiss," No Captions Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public

Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 49-92.

Susan Sontag, "Photographic Evangels," On Photography (New York: Delta, 1973), pp. 115-152.

Screening: La Jetee (1962)

Medium Specificity in Game Studies (September 27th)

Henry Jenkins, "Games, The New Lively Art"

Markku Eskelinen, "Towards Computer Games Studies"

Janet Murray, "From Game-Story to Cyberdrama"

Jesper Juul, "The Game, the Player, the World: Looking for the Heart of Gameness,"

Ian Bogost and Nick Montfort, "Platform Studies: Frequently Questioned Answers"

Screening: Run Lola Run (1998)

Windows, Frames, and Mirrors (October 4th)

Anne Friedberg, "The Virtual Window," in David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins (eds.)

Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), pp. 337-354.

Jay David Bolter and Richard A. Grusin, "Remediation," Configurations 4(3) (1996),

311-358.

Lev Manovich, "Cinema as a Cultural Interface"

Nicholas Dulac and Andre Gaudrault, "Circularity and Repetition at the Heart of the

Attraction: Optical Toys and the Emergence of a New Cultural Series," in Wanda

Strauven (ed.) The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006).

(Rec.) David Bordwell, "Prospects for Progress: Recent Research Programs," On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press)

Screening: Strange Days (1995)

Attractions and Spectacles (October 11th)

David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins, "The Aesthetics of Transition," in David Thorburn

and Henry Jenkins (eds.) Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003)

Henry Jenkins, "'A Regular Mine, A Reservoir, a Proving Ground': Reconstructing the

Vaudeville Aesthetic," What Made Pistachio Nuts: Early Sound Comedy and the

Vaudeville Tradition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), pp. 59-96.

Henry Jenkins, "'I Like to Hit Myself in the Head': 'Vulgar Modernism' Revisited"

(Forthcoming)

Tom Gunning, "The Cinema of Attractions[s]: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-

Garde;" Charles Musser, "Rethinking Early Cinema: Cinema of Attractions and

Narrativity;" Scott Bukattman, "Spectacle, Attractions and Visual Pleasure," in Wanda Strauven (ed.) The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), pp.381-388, 389-416, 71-84.

Screening: Hellzapoppin (1941)

Migratory Characters (Monday, October 18th)

Bryan Talbot, Alice in Sunderland (Dark Horse, 2007).

Will Brooker, "Illustrators of Alice" Alice's Adventures: Lewis Carroll in Popular Culture (New York: Continuium, 2005), pp. 105-198.

Christina Rossetti, "From Speaking Likenesses (1874)," Frances Hodgson Burnett,

"Behind the White Brick (1876)," and E. Nesbit, "Justnowland (1912)," in Carolyn Sigler (ed.), Alternative Alices: Visions and Revisions in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1997), pp. 50-65, 66-78, 179-192.

Screening: Alice (1988)

Spectacular Media Spaces (October 25th)

Angela Ndalianis, "Architectures of the Senses: Neo-Baroque Entertainment Spectacles,"

in David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins (eds.) Rethinking Media Change: The

Aesthetics of Transition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), pp.355-374.

Constance Balides, "Immersion in The Virtual Ornament: Contemporary "Movie Ride"

Films," in David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins (eds.) Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), pp. 315-336.

Scott Bukatman, "There's Always...Tomorrowland: Disney and the Hypercinematic

Experience," Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Super-Men in the 20th

Century (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 13-31.

Lauren Rabinovitz, "More Than the Movies: A History of Somatic Visual Culture

Through Hale's Tours, IMAX and Motion Simulator Rides," Lauren Rabinovitz

and Abraham Geil (eds.) Memory Bytes: History, Technology and Digital Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), pp.99-125.

Screening: TBA

Forms of Narrative (November 1st)

Rick Altman, "Dual-Focus Narrative," "Single-Focus Narrative," "Multiple-Focus

Narrative," A Theory of Narrative (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), pp. 55-98, 119-190, 241-291.

Screening: Gilda (1946)

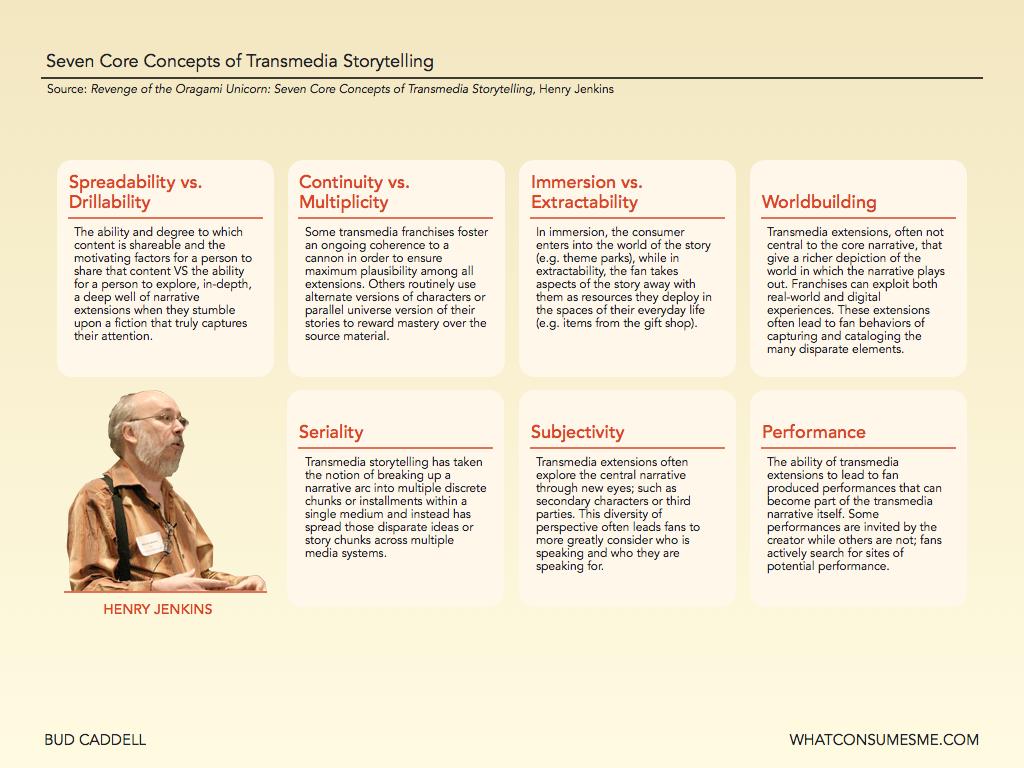

Transmedia Logics (November 8th)

Henry Jenkins, "The Revenge of the Origami Unicorn: Seven Principles of Transmedia Storytelling," Confessions of an Aca-Fan,

Screening Sleep Dealer (2008)

Hybridity and the Dialogic (November 15th)

Brian Larkin, "Extravagant Aesthetics: Instability and the Excessive World of Nigerian

Film," Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure and Urban Culture in Nigeria

(Durham: Duke University, 2008), pp. 168-216.

George Lipsitz, "Cruising Around the Historical Bloc: Postmodernism and Popular Music

in East Central Los Angeles," Time Passages: Collective Memory and American

Popular Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), pp. 133-162.

George Lipsitz, "Kalfou Danjere," Dangerous Crossroads: Popular Music,

Postmodernism and the Focus on Place (London: Verso, 1997).

Ian Condry, "Yellow B-Boys, Black Culture, and The Elvis Effect," Hip-Hop Japan:

Rap and The Paths of Cultural Globalization (Durham: Duke University Press,

2006).

Screening: This is Nollywood (2007)

High and Low in Television Culture (November 22nd)

Lynn Spigel, "Hail, Modern Art: Postwar 'American' Painting and the Rise of

Commercial Television," and "Silent TV: Ernie Kovacs and the Noise of Mass

Culture," TV By Design: Modern Art and The Rise of Network Television (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), pp.19-67, 178-222.

Screening: Best of Ernie Kovacs, other selections.

Final Presentations (November 29th)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f1b3a7b4-91f9-4e30-91f5-e6d92df9437b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c9d12056-4092-446c-8828-0bfa9beac86a)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=11925d4d-81de-459a-914c-3f4c87c8c3b5)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=df5da5da-e80b-48d2-aa66-39488916b917)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=65aecda8-b7f1-46a4-9b80-8b947160dda3)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=2e5cc314-2014-425c-9b02-88316f0d9544)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=54f406ee-808d-4a0a-a566-290e1559aa88)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1a1ecca7-cede-4c4f-a48b-d9d0ae1e71a2)