Yesterday, I introduced you to Matthew Weise, a producer from our GAMBIT lab, and a key figure behind our games research efforts. Today, I wanted to introduce you to another researcher who recently joined the CMS community -- Erin Reilly, Research Director of Project nml.

The New Media Literacies (NML) project, funded by the MacArthur Foundation, is developing a theoretical framework and curriculum for K-12 learners that integrate new media tools into broader educational, expressive and ethical contexts. NML is partnering with classrooms and after school programs around the country to test curriculum prototypes created by CMS students and program affiliates.

Before coming to MIT, Reilly was co-creator of Platform Shoes Forum's model program Zoey's Room, a national online community for 10-14 year-old girls, encouraging their creativity through science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Zoey's Room has proven results in advancing STEM and Media Literacy skills. In 2007, Erin received a national educational Leaders in Learning Award from Cable in the Classroom for her innovative approach to learning through Zoey's Room. A recognized expert in the design and development of thought-provoking and engaging educational content powered by virtual learning and new media applications, Erin has been a featured speaker, panelist and keynoter at several industry events. Erin serves on the Working Committee of Pop!Tech (http://www.poptech.org), an internationally acclaimed technology event that can be seen on PBS and the Technology Committee of the Maine Arts Commission.

Knowing how many of my readers have a strong interest in the use of new media for education, I asked Reilly to share some of her insights from working on Zoey's Room and to give us a preview of what you can expect to see from Project nml in the coming year.

Tell us about Zoey's Room. What were the goals of this project and how do you measure it success?

Zoey's Room is a safe, online educational community developed by Platform Shoes Forum to creatively engage 9- to 14-year-old girls in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM).

The goals of Zoey's Room are to encourage middle school girls to:

• Learn science, technology, engineering and math skills in a fun, collaborative online environment by completing online activities and offline challenges on their own or in a group.

• Behave responsibly and ethically online and to be Internet Safe

• Participate and share in an informal learning environment, and

• Be better prepared for the technological demands of a future workforce.

Fewer than a dozen Science, Technology, Math, Engineering (STEM) websites are currently available online for middle school girls right now. Of them all, Zoey's Room is the only STEM website that features a multicultural character "Zoey" who appeals to both rural and urban girls. Zoey hosts her own chat room for girls every day after school. She encourages girls to explore STEM topics through fun challenges called Tec-Treks,ï€ ï£ª that expand their knowledge on a range of 21st century skills. Additionally, each month, Zoey leads informative chats with "Fab Female", women role models who have STEM professions. This unique interpersonal connection, along with the collaborative nature of the Tec-Treks, encourages girls to become more interested in STEM careers.

We measure the success of Zoey's Room not on the number of its members but on the girls' safety, progress in academic fields, and retention in the program. The extensive research behind Zoey's Room allowed us to develop a practical application, which includes an on-going assessment of each member's participation and learning. Evaluative tools include a benchmark survey taken when a girl first joins the program, annual assessment polls, and one-on-one feedback from online members and adult facilitators.

Specifically, a sample of 100 girls participated in the Zoey's Room 2006-2007 benchmark and final survey. When asked the answers to very specific STEM questions we put to them in the survey, the majority of girls got 12 out of 13 of the answers right--which proves to us that they actually learned terms and concepts and principals of certain STEM topics by doing the various Tec-Treks. But beyond statistical measures, what girls are saying about Zoey's Room matters the most.

"Math is my favorite subject - I'm (now) interested in numbers and problem solving"

"We need more ideas like Zoey's Room; being a girl is hard and we need all the support we can find since it's hard to discover that at home, with our friends, or our schools."

"I think that Zoey's Room is the best idea in the whole entire world. On Zoey's Room, a safe environment is provided where questions can be answered and girls actually have a voice."

What factors have historically limited young girl's comfort with Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math? How has Zoey's Room overcome these problems?

Reports like "Shortchange Girls, Shortchange America" (1991) and "Gender Gaps" (1998) by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) were the catalyst for starting a program like Zoey's Room. Through aggregated research and internal studies, these reports uncovered the need for schools to provide equitable education for girls in the areas of STEM. AAUW found that to instill math, tech and science skills in girls; we need to educate girls to be designers, not just passive users of technology- and Zoey's Room encourages that. Given the social and collaborative nature of girls, a girls-only self-paced learning environment seemed a natural platform. The next step was to make this environment engaging and attractive to girls by including community tools.

Though girls today are more apt to be interested in technology, they are still not pursuing further as advanced courses or career aspirations. According to a more recent report," What We Know about Girls, STEM, and After-school Programs" (Cheri Fancsali, Ph.D. for Educational Equity Concepts) girls are much less likely to major in science-related fields in college; less likely to complete undergraduate and graduate with STEM degrees. Beyond that, women comprise a disproportionately low percentage of the STEM workforce, earn less, and are less likely to hold high-level positions in STEM careers. What does that mean for our society? Today, eight of the 10 fastest growing jobs in the U.S. are computer related. By 2010, jobs in the technical and mathematical fields are expected to increase by 67%. If this trend continues, not only does it seriously cripple young women's potential financial earning power, but as more jobs in the future demand technological proficiency, this trend can be a detriment to the nation's intellectual resource pool.

In the last five years, numerous studies have documented concrete methods to get girls re-engaged into learning "hard skills." Programs for girls combining hands-on activities, role models, mentoring, internships, and career exploration have improved girls' self-confidence and interest in STEM courses and careers and helped reduce sexist attitudes about STEM (Campbell and Steinbrueck, 1996; Ferreira, 2001).

The AAUW Commission also stressed the need for adult female role models to engage younger females in the areas of science, technology, engineering and math for girls to begin reshaping their own perceptions about these fields as career choices. A recent Girl Scout Research Institute (GSRI) study showed that girls tend to make career choices based on their role models rather than their academic interests.

Joseph Bernt, an Ohio University professor of journalism, and one of the authors of a nationwide study funded by the National Science Foundation about the media's influence upon middle school children found "this age group spends more time interacting with media than in school or with family, or even with their peers. This means that media has to start providing better role models for girls. Zoey's Room is our example of creating a fun, creative, positive use of media. By harnessing the media for education, we hope to inspire girls with other role models.

In a recent column, I argued that the term, "digital natives," masked lots of differences in young people's access to and participation within digital media. What kinds of differences in skills and access have you observed through your work on Zoey's Room?

I think we've grown up in a culture that we have to label everything, but by doing this we limit the truth of who people really are. Using labels like digital natives and digital immigrants is just another way of stereotyping people. Anyone who's participated in community online knows that it's these places where stereotypes are broken down. The anonymity of the web allows for the girl you'd never hang out with in school to become one of your closest allies online. It's a congregation of girls interested in a particular subject rather than hanging out on a particular social norm that sets precedence in the school cafeteria.

Children have to learn technology skills just like we adults. The only way they are going to learn the skills are by trying it out or asking for help. This metaphor makes it sound that every kid is a native to the digital environment. It doesn't take into account that kids and adults all have different experiences with digital technology. And it also doesn't take into account the guidance and supervision that happens in communities and the positive results occurring when an informal mentorship happens between an adult and a child online. It really depends on how much access they have to the technology in order to be comfortable. These skills are unevenly distributed across our population and can easily be seen in the Zoey's Room membership. We have many home-schooled girls using Zoey's Room who are much more savvy online than girls who doesn't have a computer at home and only get to use the computer when she meets with her after-school Zoey's Room club.

The chat and message boards on Zoey's Room are filled with peer-to-peer sharing of how to do something online. (See the below image for example of girls sharing how to change fonts within chats).

The message board tech tips wouldn't be filled with this information if girls came into the program knowing how to do everything digital.

I also argued that adults might have more to contribute in helping young people adjust to new technologies than the phrase "digital immigrants" implied. How did you harness adult expertise through Zoey's Room?

We harnessed adult expertise in Zoey's Room by creating a mentoring pipeline through our Friends of Zoey and Fab Female components. High school girls can apply to be "Friends of Zoey", which are junior staff members who interact online with girls and encourage them in Tec-Treksâ„¢. The FOZ began as an internship program for girls who have aged-out of Zoey's Room but still wanted to stay involved and developed into these girls being the community hosts of Zoey's Room as well as keeping content evergreen.

As I mentioned earlier, Fab Females are female role models who have professions in STEM. Past Zoey's Room "Fab Females" have included a NASA Food Technologist, Microsoft IT manager, a marine biologist, a paleontologist, and digital artist, designers and film makers. Fab Females have asked to stay involved beyond the chat session. With an increase in membership this year, we're opening up a space in the community for on-going interaction between Fab Females and the members.

Not only are our Friends of Zoey the glue to the online community, but also these girls build leadership skills by recruiting and interviewing our Fab Females to conduct online chat sessions. They also work with these Fab Females for additional Tec-Trek activities.

Online safety was a central concern of your work on Zoey's Room. Many adult fears about young people's experiences online are misguided, but some are not. What do you see as the most realistic concerns and what steps did you take to address them?

Since we work with children under the age of 13, the biggest concern is following the guidelines of COPPA, and we worked closely with the FTC to ensure our registration was COPPA compliant. However, this doesn't guarantee that a person signing up is who they say they are and we all know how easy it is to change your birth date to make you whatever age you want to be. So, how do we protect girls from encountering just anybody on our site?

We've partnered with a 3rd party verifier to ensure all adults who register a girl for an account are subject to identity verification. Before confirming a girl's membership to Zoey's Room, our process verifies the data collection of adult registrants to ensure they are who they say they are. This is a reactive approach and does not provide the answer to safety but we hope this extra step will deter folks who are joining the community for reasons other than its intended purpose.

Past the access point, Zoey's Room creates a proactive approach to safety and ethics by training Friends of Zoey how to help moderate and monitor the chat room and message boards every day for ongoing protection of its members. We also create an environment where members watch out for each other and know the guidelines they need to follow to participate in the community... and I think this is the best approach to take. I conduct adult workshops and stress to attendees how important it is to have open conversations with your kids and help educate them of proper conduct online.

Lately, we find the biggest concern is not safety but ethics. We've found that when confronted with someone prying too much, they usually quit out of the program and shut down. Their natural instincts kick in. However, it is mob mentality and bullying that causes the most damage. Zoey and Friends of Zoey provide peer-to-peer guidance in how to handle the situations and have been known on more than one occasion to be the bridge to acceptance of each other.

What did you learn from the work on Zoey's Room that will help us expand the community around Project NML?

The first thing we started with this year was defining our audience. If it's for teens, make it for teens. Don't worry about the adult. If teens like it, the adults will join in. If teens don't like it, you and the adults will always feel like its work.

"Today's American teens live in a world enveloped by communications technologies," states a 2005 Pew Internet and Life Report titled "Teens and Technology.

Whether adults are comfortable with this technological revolution or not--it's happening. According to the Pew Report more than 87% of teens and tweens between 12-17 are using the Internet and their preferred method of communication is online in the form of Instant Messaging, Chat Rooms, and Social Networking sites with older girls taking the lead nationally as the "power users" of the Internet.

In Zoey's Room, we foresaw this trend in 2002 when we created a moderated chat room for girls only with the sole purpose of appealing to girls' natural collaborative and communicative natures as a platform to introduce "stealth" education in the form of Tec-Treks and role models.

We also saw the success of having a place for members to showcase their work and get feedback. Each of the Tec-Treks is project-based and not yes or no or multiple choice answers. Tec-Trek projects are loaded for not only Zoey and her friends to give feedback but also the other mentors.

I've seen first-hand that community is the glue to learning online. If you lose community, then you might as well be reading a book on your own without ever joining the book club for discussion.

I hope to take the Zoey's Room "pipeline" community to Project NML. This approach encompasses the traits recognized in participatory culture, including:

• Low barriers for artistic expression & civic engagement

• Strong support for creating and sharing what you create with others

• Some type of formal mentorship (pass it along to newbies)

• Members contribution matters - reinforce your contribution is important

• Some degree of social connection matters

And first and foremost, I bring the knowledge of lessons learned in the field. Of having taken theories and created a successful digital learning application. Having processed what works and doesn't work will help Project NML be successful and hopefully push the digital learning community further.

What have you learned through working on Project NML so far that helps you think differently about Zoey's Room?

In your graduate proseminar on Media Theory and Methods, you ask your students to interview a media maker and to try to get a sense of the theoretical assumptions underlying their work. Zoey's Room has been a practical application but the research that we looked at to develop Zoey's Room was girls and STEM. We were media makers so we didn't look at the media theories to develop... we just did it.

Since becoming Research Manager for Project NML, I realize that we intuitively created a participatory culture for members of Zoey's Room. Even though the program was about encouraging girls in STEM, it is an example of a shift in media literacy from thinking about what media does to helping change our mindset to what choices we make as users / producers of media. This is an active way of participating in media instead of the passive way to what media we consume.

We cannot have media literacy be a separate class / add-on at the end as we've seen in the past decade. Instead it needs to be infused cross-curricular.

Reviewing the skills against Zoey's Room Tec-Treks, I see these skills come into play both in and out of the digital realm. There are connections of how kids are connecting in the digital realm to what they should be doing in the classroom. This skill set is not just about high-tech activities. This is an opportunity to help kids acquire skills on how they process knowledge so that they can participate in a new way.

We've been rethinking the goals of Project NML since you've come on board, but the impact of that rethinking has not yet been made visible to the public. What can you tell us about the Project's future plans?

This semester, we've created new approaches to working on this project that really has allowed everyone on the team to understand the goals we want to deliver.

We are currently immersed in production with a goal to re-launch Project NML's interactive website Fall 2008. The new website will allows users to create their own pathways through our exemplar library and have users create and add their own material to the exemplar library.

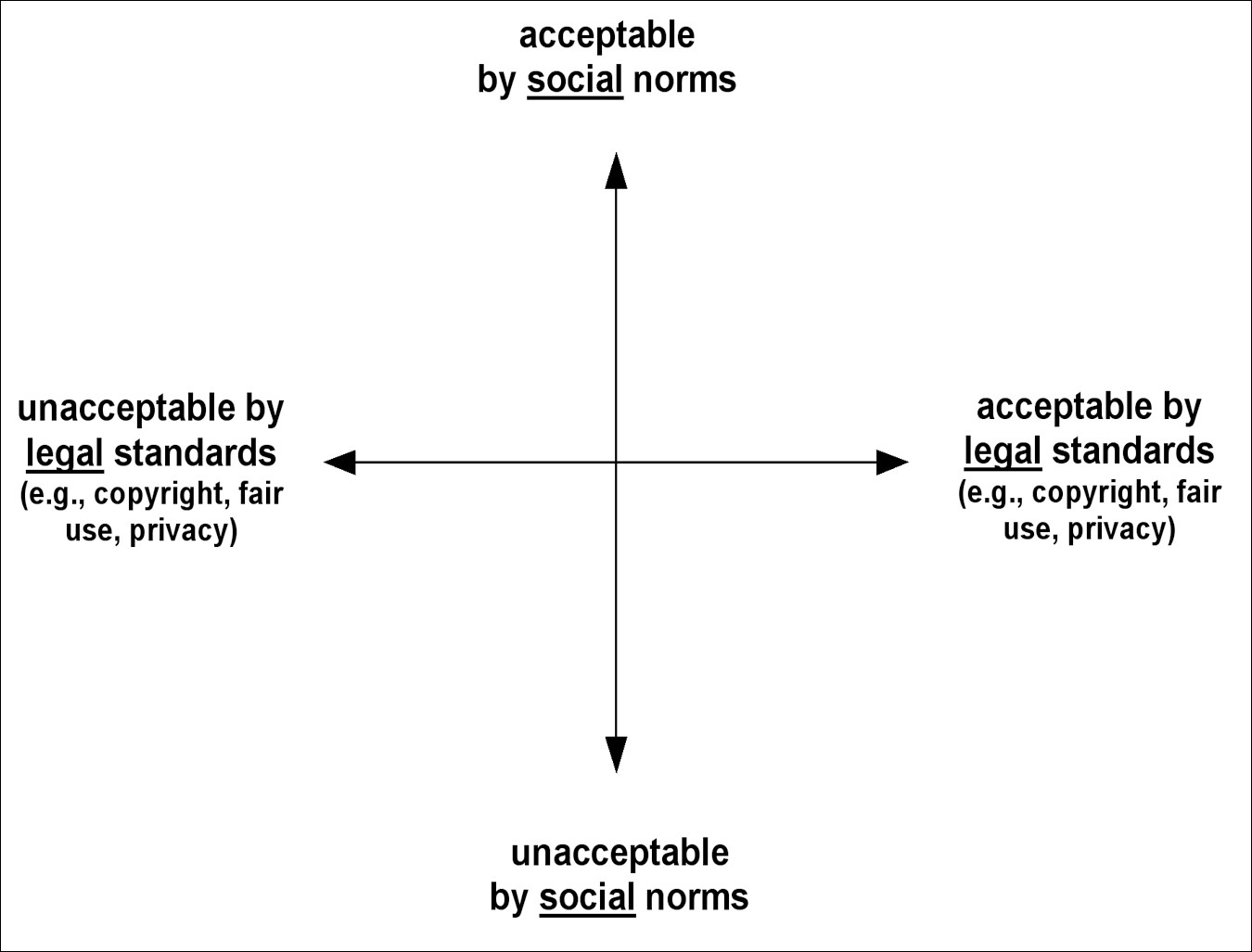

The exemplar library is a sampling of the participatory culture framework centered around the 4 C's ...how do we Create, Connect, Communicate and Collaborate. It is an interactive learning library that creatively encompasses a best practice video with an online activity and offline group challenge. The library is built on an extensive backend database where each piece is tagged on multiple traits including; the 11 new media literacy skills, media tools, traditional subjects, and the 5 ethical categories created by Harvard's Good Play project.

The exemplar library will also have some online activities that highlight our collaboration with Harvard's Good Play project. These activities will provide a springboard for discussion on a dilemma centered on one of the five ethical categories: identity, ownership / authorship, privacy, participation and credibility.

As community is the glue to learning online and Project NML will provide a venue for all users to answer the question, "How do YOU create, connect, communicate and collaborate?" This type of user-generated content will allow for the library to expand by the community and for new best practices to emerge, be shared and discussed.

Whereas Project NML's exemplar library is informal learning directed to the teen, the Teacher's Strategy Guide: Education in a Participatory Culture provides structure for a teacher to integrate the new media literacies into the traditional classroom. The framework includes a lesson plan, with extension link of ways to extend the 1-2 class period lesson plan into a semester or year-long project with options to tie to other class subjects as well as a side bar that provides entry points to engage the student through the Project NML exemplar library.

We currently are in development of our first guide called Moby Dick: Remixed and are currently seeking 10 high school English / Literature teachers to test our Teacher's Strategy Guide: Education in a Participatory Culture in Fall 2008. Moby Dick: Remixed help students to better understand the appropriation and transformation of pre-existing cultural materials which shaped some of the most cherished works in the western cannon. The guide provides a set of lesson plans that juxtapose Herman Melville's Moby Dick and Ricardo Pitts-Wiley's theater performance Moby-Dick: Then and Now and is a clear example of the new media literacy skill: appropriation.

Our next steps are to develop material for history / geography teachers. The next guide will be called Weaving the Threads - Social Mapping to Global Citizenship. This project will couple children's interest in cultural diversity with our own interest in the New Media Literacy skills required to process new forms of simulation and representation, producing a project which challenges participants to think about their relationship to their space in fresh new ways. Such a curriculum should enhance traditional social science education, while allowing students to become active participants in their learning rather than passive recipients, because it is in this approach that we help our children become global citizens.

Mentorship will continue with expansion into a media franchise. One of the motivating factors of the community is to develop a character based on the 4 C's. This character will be customizable per user and provide rewards for motivation within the community. This character has the potential to be the lead character in an e-zine style program targeting Tweens. With the collaborative learning community online, the strategy guides deployed to the classroom and the television series, Project NML will be a transmedia experience that helps foster the new media literacies.

If you'd like to become a test school for Project nml, please contact our outreach coordinator Jenna McWilliams at .

Want to know more about new media literacies? If you live in the Boston area, you might want to check out a forum being held at the Brattle Theater at Harvard Square on Dec. 12, 5:30 pm:

MIT Press And The MacArthur Foundation Present

Totally Wired: How Technology Is Changing Kids And Learning

Are digital media changing how young people learn and play? A public forum featuring Howard Gardner (Harvard Graduate School of Education), Henry Jenkins (MIT), and Katie Salen (Parsons School of Design), hosted by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, as part of its $50 million digital media and learning initiative. The panel will be introduced by Jonathan Fanton, MacArthur President, and moderated by Connie Yowell, MacArthur's Director of Education. Free and open to the public.

Free and open to the public

The event is designed to celebrate the launch of a new series of books being released by MacArthur and the MIT Press which share state of the art research on how kids learn and what they encounter in the new media landscape. The first six books in the series are being released this month and will be available online as of December 12.