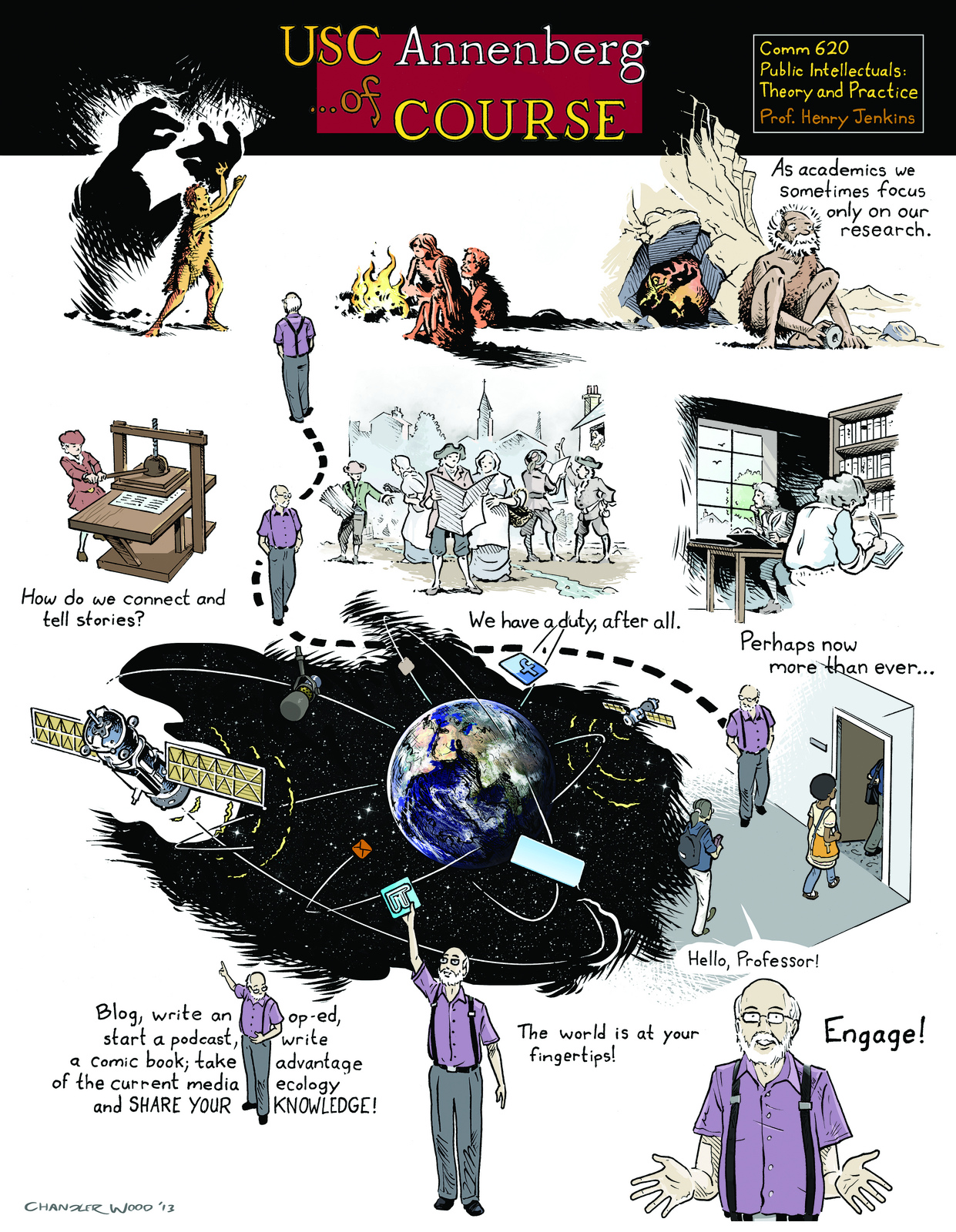

In the “Participatory Poland” report a group of Polish aca-fen makes a preliminary attempt towards defining the specificity of an Eastern European country’s participatory culture shaped both in the communist and post-communist periods. By placing the development of selected fan-based activities against a broader socio-historical background, we are trying to capture the interplay between the global and the local context of participatory culture, as well as take preliminary steps towards making its Polish branch available for academic research. Thanks to Professor Henry Jenkins’ incredible support, we are able to share the first, though by no means final, results of our investigations with aca-fen worldwide. The posts included in this report deal with several examples of Polish participatory activities, namely, the literary and media fandom of speculative fiction and role-playing games; comics fandom; fandom of manga and anime; historical re-enactment associations; and the prosumerist phenomenon of bra-fitting. While we are planning to continue and expand our research, we hope that its samples presented in this report contribute to the exploration of participatory culture.

Notes on comics fandom in Poland

Michał Jutkiewicz, Polish Department Jagiellonian University

Rafał Kołsut, Polish Department Jagiellonian University

- Emergence of comics fandom in the 1980s

Until only a few years ago, history, and especially the 20th century, was the predominant subject of Polish comics. Nowadays that is not the case as more and more psychological and autobiographical stories or even superhero fictions are published. Nevertheless, historical comics, lavishly subsidized by cultural institutions, are still the essential part of the comics’ scene. This obsession with history may result from the fact that the situation of comics in Poland has always been influenced by national political and historical struggles.

After the war, when the communist government was established, the official attitude towards comics was somewhat ambivalent. On one hand, comics were perceived as a medium developed in capitalist countries and representing the corrupted American lifestyle. It is interesting that a lot of communist propaganda’s arguments and accusations—for example, those concerning promoting violence, sex and children’s demoralization — sounded as if they had been taken directly from Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent.

On the other hand, comics were perceived as a useful tool of propaganda directed especially towards kids. Forming the future citizens of a socialist state became an important issue in the 60s, when more and more comics were published and read by young readers. Probably the most popular were Tytus, Romek and A’Tomek (published from 1957 till today) by Papcio Chmiel and the series about Captain Żbik (Wildcat) created by Władysław Krupka and published from 1967 to 1982. The former series contained slightly surreal stories about the adventures of two scouts and an ape, which were nevertheless packed with an educational and moralizing content. The protagonist of the latter, was a lawful and honorable policeman fighting evil imperialist agents, who plotted against Poland and tried to destroy it.

Many factors influence the fact that, it was impossible for a community of fans to establish itself: among others the young age of the group at which comic books were targeted, a brazen propaganda of communist values and an absence of comics from other countries. However, the aforementioned comic books were a starting point in the process of familiarizing young people with the medium and encouraging some of them to search for more examples.

The first signs of an emerging community of comics fans could be seen the early 80s and was related with S-F fandom emerging at the same time. Just as before, the formation of both fandoms was at that time closely connected to the political situation in Poland. The end of the 70s was marked by the rise of the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement, which was fulfilling the role of the political opposition. It was also a moment when people in their twenties were looking for some new cultural and social structures to identify with. punk music, with its distinctive fashion and seditious message, was one of the models to follow.

In comparison to the music-based subculture, which was considered by officials as degenerated, the fans of S-F were perceived by the state institutions as harmless, notwithstanding the fact that the genre was developing under the influence of such authors as Stanisław Lem, Kir Bulychov or Strugatsky brothers, who tried to sneak into their novels a veiled critique of the communist system and ironic allusions to the situation in their countries. S-F literature of the 80s was a very particular mixture of escapism and political engagement. A status of a fan and a member of a club of SF literature was very often considered as a political act although it was not always one’s conscious choice.

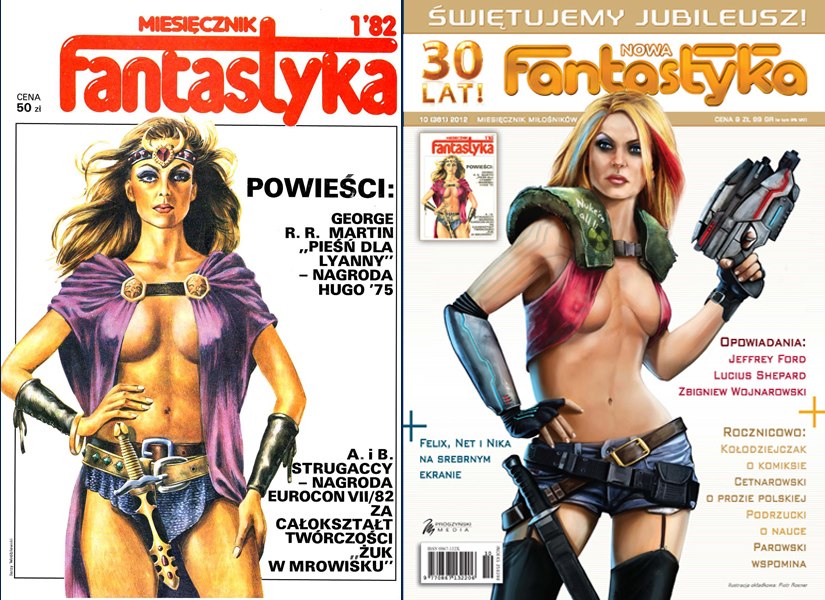

The most important Polish magazine devoted to SF, Fantastyka, was established in 1982. It was the first publication of this kind in Poland, and its main goal was the popularization of sci-fi and fantasy literature, as well as the animation and coordination of activities of fan clubs, which were gradually set up all over the country. Comics were the subject of the one of the biggest discussions in the first issue of Fantastyka as the editorial board was debating whether to publish them in the magazine or not. Regardless of those discussions, sci-fi and fantasy comics were gaining popularity, mainly due to the fact that some Polish illustrators, especially Grzegorz Rosiński and Bogusław Polch, who both started their careers creating propaganda comic books in the 70s, have been recognized on Franco-Belgian and German markets. One of Polch’s most recognized series, based on Erich von Daniken’s theories, called Die Götter aus dem All was being published in Germany in the years 1978-1982. Meanwhile, Rosiński began a cooperation with such renowned script writers as Jean Van Hamme (making Thorgal) and André-Paul Duchâteau (Hans). Till this day Rosiński is considered an iconic person in the field of Polish comics and the Polish fandom, and an important guest at all comics conventions.

The editors of Fantastyka decided to print four-page long comics and publish comics-related reviews and news from abroad. The community of comics’ fans was growing so strong that soon a separate comics–oriented addition to the magazine was published from 1987 to 1990. Its name was Komiks – Fantastyka and it was the first attempt to build not only a magazine with comics in it but also a publication which would animate comics’ fans. It also tried to establish a foundation for professional comics criticism as it included articles about such academic theorists as Thierry Groensteen.

“Komiks – Fantastyka” maintained the sci-fi and fantasy profile of Fantastyka. publishing titles like “Hans” (renamed as “Yans”) and “Rork” by Andreas. The majority of translated comics at this time were Franco-Belgian, which created a peculiar generation gap among comics’ fans. Those raised in the 80s tend to prefer stories with realistic and detailed illustrations and strong world building typical of European comics. When in the 90s American superhero comics finally arrived in Poland, another generation of fans grew up. They were more interested characters and action than in with the detailed drawings. This difference can also be seen in the works of Polish comics creators, who in their youth were influenced either by the European style or by the American models.

Only one title published in the 80’ had a major influence on the shape of Polish comics and it can undeniably be called a masterpiece of its time. It is called Funky Koval and was written by Maciej Parowski and Jacek Rodek and illustrated by Bogusław Polch. It was first published in parts in Fantastyka since1982 and then as a whole in Komiks – Fantastyka until 1990. Funky Koval is important not only because of the story it tells but also, if not mainly, because of its cultural influence and the role it played in the integration of the fandom. No other comics of this time would gain a cult position and become such a prominent point of reference for works published later.

This comic combines all the influences mentioned above: politics, sci-fi and fans. The story centers around a private investigator named Funky Koval, living in the USA in 2080. His adventures are focused on his struggles with evil corporations and corrupt politicians. There is a lot of action but it is not the main point of this comics. The authors of Funky Koval followed the example of literary texts published in Fantastyka and decided to pack their comics with intertextual games and allusions to the current political situation in Poland. The sci-fi façade enabled to avoid censorship and to build an ironic critique of the communist regime. Nearly every evil character was based on a real-life member of the communist party, and known to readers from the TV screen.

Moreover, the hero’s adventures contained allusions to Martial Law enforced in Poland from 1981 to 1983. Hence, readers of the comics were asked to participate in the game of who-is-who, and this aspect of Funky Koval was the key to its popularity. The act of decoding a hidden message was a ground for building a sense of belonging to a greater community, as their members identified themselves with its hidden political agenda, so that the act of decoding became an act of contestation.

This level of intertextual games in Funky Koval was fairly easy to decrypt for everybody, but the authors went even further and decided to put not only public persons in their creation, but also people known to them personally. Indeed, a lot of characters in the comics are based on people active in the fandom of the 80s. To fully read it, one had to be a member of the community and know sci-fi and fantasy conventions, In this way Funky Koval strengthened the fandom and gave it some identification.

Although the roots of Polish comics fandom are entangled with the community of sci-fi and fantasy fans, it is really interesting to observe how in the 80s it slowly tried to emancipate itself and managed to separate completely in the 90s. At the beginning of the last decade of 20th century comics community started to organize their own conventions strengthening the bonds between community members, which made the group less fragmented and more hermetic.

2. Situation during the 90s and 2000s

After the political transformation of 1989 Poland was violently struck by a tide of Western culture, almost unknown to an average Polish audience until that time. A phrase effectively describing that period would be “the time of catching-up,” mostly with regard the works of pop culture. Independent distributors were (sometimes illegally) bringing from abroad absolutely everything that had any chance of selling to the newly ‘born’ consumers who were ravenous for novelty. The era of high-volume publications of Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza (The National Publishing Agency) as the monopolist was gone forever. In 1990, after receiving the approval from the headquarters of Semic Press AB (a company publishing comic books in Scandinavian countries under the license of, among others, Marvel Comics), a Polish-Swedish company - TM Supergruppen Codem (later renamed as TM-Semic) published the first two monthlies in Poland. They contained adventures of the American superheroes: Spider -man and Punisher.

Those comic books had exactly the same format as the original ones, and only the volume was different – every month two stories were presented on 52 pages (in order to „catch-up” with the ongoing series in the USA). In time, having become very popular, Punisher was extended to over 100 pages, but for the sake of costs it was published only in black&white.

Making the first baby steps but noticing a great interest of its readers, the publishing house momentarily expanded its offer. Now, every group of the younger consumers was to receive “something special”. As a result, Barbie, Moomins, Casper, Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles or Garfield appeared in kiosks. The rights for Davis's comics were soon bought by Egmont Polska (part of Egmont Group from Denmark) – the second great distributor for kids and teenagers, publishing also Bugs Bunny and Donald Duck (the latter is still published).

Thanks to the fanclub pages administrated by teenage comic books fan Arkadiusz Wróblewski, the more and more active community of superheroes’ fans started to form. The same year the album Batman/Judge Dredd: Judgment on Gotham was printed on thick paper and in hard cover. Nobody in Poland had published a comic book of such a high quality ever before. Thanks to the company, readers were presented with Knightfall, Dark Phoenix Saga or The Death of Superman. Nevertheless, consumers, familiarized with more and more aspiring titles, had also greater expectations. Simple stories about superheroes stopped selling. Issues dropped down and series after series started vanished from the market. The company collapsed in 2003. It’s place was taken by Egmont, which was not trying to sell the comic books but focused on publishing TPB – cult series for adult reader such as The Sandman or Preacher.

The comic books community calls the 90’s “The Time of Troubles,” during which Polish comics virtually disappeared from the market. The fall of Bogusław Polch’s studio which was working on the graphic adaptation of Andrzej Sapkowski's The Witcher in 1995 is the caesura. Authors active during the time of the People’s Republic of Poland completely withdrew and started to look for other ways of earning money (with several exceptions, for example that of Henryk Chmielewski, the author of the popular young adult comics about Tytus the chimpanzee). Former stars, such as Janusz Christa or Szarlota Pawel decided, that it was not profitable to draw in the new political system.

The tradition was broken – also on the level of master-student relations. The ending of the 20th century belongs to self-taught, underground artists among whom the most active are the authors of hardcore punk fanzines: Dariusz Palinowski, author of Zakazany Owoc (Forbidden Fruit) and Krzysztof Owedyk, author of Prosiacek (Piglet). They both laid the groundwork for the constitution of the so called comic “xeroprasa” (photocopy press). Drawn in back&white and photocopied magazines (and sometimes one-shots) were sent directly to friendly readers from all over the country, that were subsequently photocopying them again and passing them on, usually for free. The scene of comics community fanzines was very similar to its prototype from the United States, but much smaller, of course, and developing almost 30 years later. Zines rose and fell, authors changed titles and places of distribution. The most important titles included Mięso (Meat), Azbest (Asbestos), AQQ and Ziniol (today it is a professional web magazine). A completely new environment formed up, created by people who are active until this day.

In the early 1990s, the Contur group started organizing the annual Ogólnopolski Konwent Twórców Komiksu (National Convent of Comics Authors) in Łódź (currently International Festival of Comics and Games – the most important meeting of Polish comic fandom). The biggest attraction of the festival was the short story comics contest, which quickly became a tradition.

Although many of today’s well established careers had their debuts in that contest, most of the young and promising authors, whose success was foretold at the time, never published anything – creating full-scale albums was absolutely non-profitable, since none of the domestic publishers was even remotely interested in publishing them. In the course of time, that phenomenon was called “Masters of the first board” syndrome because of the declarations and prologues to the stories which would never be created.

Everything changed thanks to Produkt (Product) magazine. Published since 1999 by Independent Press company, Produkt was presenting the latest output of the Polish authors. Today’s stars of Polish comics debuted and published on Product pages, including Michał Śledziński (from Azbest); Minkiewicz brothers; Karol Kalinowski; Ryszard Dąbrowski, the creator of the Likwidator (Liquidator) – a masked anti-hero who is an eco-terrorist and a serial killer; or Rafał Skarżycki and Tomasz Leśniak, the authors of George the Hedgehog series.

The comics published in Produkt belonged to the mainstream due to the magazine’s scope and professional distribution, but at the same time they were free from any publishing or editorial control. They contained violence, nudity, vulgarisms, satire against the government, the Church and authority in general. There was no taboo or censorship. The most important series that was published on Produkt’s pages, Osiedle Swoboda (Liberty District), created by the magazine’s Editor in Chief, Śledziński, was focused on young people’s everyday life in Poland. During its five years of existence Produkt not only brought together the most engaged authors and enlarged the number of regular consumers of graphic stories of domestic provenance but, most importantly, set the direction for Polish comics for the following years.

In 2005 Paweł Timofiejuk, currently the most important publisher at the Polish market, started a publishing line called Komiksowa Alternatywa (Comic Alternative) in frames of which he presented the cult albums of authors of fanzines, previously known only from the comic photocopying press. The artists, so far bereft of the chance to show their work to the world, could finally present the results of honing their skills. That so called “airing of the drawers” lasted for two years.

The time of the growing prosperity caused by the dissemination of cheap digital printing began. Publishing both the albums and the professional magazines privately became easier than ever before. Many independent publishing houses have been created, among which some are focused on publishing Polish authors only. Others are diversifying their offer, combining the most important works of the European authors with the local novelties. Polish artists are focused on creating authorial albums that they work on for months or sometimes even years.

Because of the very low sales of comic books and a small number of their readers, creating comics is not a profitable job. Polish comic books community which is the basis of the market has around 3 000 members, with a scarce addition of casual readers, who are usually interested just in one particular series. There is no such job as a “comic book author” in Poland. The graphic, the scriptwriters and the publishers are keeping regular jobs, while they work on comic books after hours and at weekends. The pay in the European standard can be provided only by the contract for educational albums devoted to the history of Poland (especially WWII ) and mostly funded by the government. Still, despite the difficult financial situation and the tiny market, every year 400 new comic books (mostly counting more than 48 pages) are published, about 120 of which are Polish authors’ productions covering ground from superhero stories of to formally experimental artistic albums.

3. Comics fandom and the Internet in the first decade of the 21st century

Around 2000, more and more households had Internet connections, which exerted a huge impact on different kinds of fandoms, fans of comics included. The first visible effect of the Internet’s growth in Poland was that the majority of printed comics magazines were discontinued one by one. Their main function in the 90s was to inform readers about newly published works and the schedules of upcoming conventions. The pages of comics magazines featured debuting authors who in turn could receive a critical feedback.

Yet none of these publications was able to build authority strong enough to act as a platform of institutionalized criticism. Probably one of the reasons was that the community was so small that readers and creators were closely linked anyway and could get feedback about their work immediately and directly just through personal connections. Very few people with academic background, such as Jerzy Szyłak and Wojciech Birek, put an effort to write more complex reviews, but those articles were not received well. That is why there was never an ongoing discussion about the condition of Polish comics during the 90s or at the beginning of the 21st century even though a lot of comics magazines were published.

From 2000 the Internet became the main source of information about newly published works and publishers’ plans for subsequent months, taking away one of the main reasons for the existence of not only comics magazines but also of other fan centered periodicals. The same thing happened to magazines about role-playing games – the last issue of one of the oldest such magazine, called Magia i Miecz (Magic and Sword), was printed in 2002 – and a little bit later, around 2005, to magazines about video games.

Also debuts began to be published online. The debut of the first Polish webcomics occurred during that period, which came as a shock especially to the community of comics fans and creators. Suddenly, the old and highly ritualized ways of publishing were losing their significance. Before, one had to show his or her work to someone in the community to be published. Even such an anarchistic genre as zines were following this procedure. The highly ritualized act of publishing was a social activity requiring contacts and acceptance of the community.

Comics on the Internet could appear on websites without all that. Thanks to the WWW new energy, comics fandom, which was becoming a little stale with no fresh blood (because of the declining numbers of comics readers), rejuvenated as a new generation of authors appeared. As early as in 2004 the anthology, Komiks w sieci (Comics on the Web) was published, which is a significant fact exemplifying how massive this wave of new creativity was.

Up to that point a lot of activities of the fandom were possible only a few times in a year, when people met on conventions, but thanks to the availability of the Internet, it could be done from a distance. Clearly, the comic fans needed an electronic forum where they would be able to discuss their interests. One of the most interesting and still active websites is esensja, which started as an e-zin in 2000. After 13 years it continues the tradition of imitating paper magazines with a monthly set of articles published along with news and reviews, which appear on a daily basis. A significant feature of this website is that, continuing the tradition of Fantastyka in the 80s, it tries to bring together different communities, for example fans of genre literature and movies, comics and games. Its popularity shows that there are fans who do not need to relate to a very narrow group of people with the same interests.

Another fascinating Polish website about comics is Zeszyty Komiksowe (Comics Notebooks). As is the case of esensja, this portal is connected to a magazine which has appeared irregularly in a paper form since 2004. The most important feature of Zeszyty Komiksowe is that every issue is devoted to a particular subject and that it publishes academic papers. It would be easy to dismiss the website because it usually publishes just news and sometimes reviews, but one element makes it very useful. Under the link “kopalnia” (mine) one can find a repository of academic articles about comics. It is a community based project, so it depends on people willing to share their work (usually BA or MA dissertations) to build collectively a comprehensive list of references. At the moment it has 1177 items. This is very admirable, taking into account the non-existence of comics studies in the Polish academic curriculum, as there are still very few academics writing about comics. Of course, many articles put on the Zeszyty Komiksowe website lack academic rigor and are a little naïve, but they are still a great example of the way fans are trying to fit with their fascination with comics into academic discourse.

The last, and most important website for Polish community of fans, which has somehow become the center of Polish comics fandom is called Gildia Komiksu (the Comics Guild). It is a part of a bigger portal, gildia.pl, which has been active since 2001. The basic assumption of this website is completely opposite to that of esensja. Esensja tries to unify different communities of fans, while Gildia is divided into many “guilds” with different subjects of interest (conventions, movies, tabletop miniature games, computer games, tabletop games, horror, supernatural, RPG, Star Wars etc.), so that different fans can find a content of their interest. This segmentation was a starting point for comics fandom to grow in its own closed environment.

The main purpose of the website, as in the case of the ones mentioned above, is to give users the news and publish reviews, but the most important part of the portal is a forum, which during the 11 years of its existence has grown and attracted the attention of the most active people in fandom. After such a long time it is easy to see how the number of posts and authority of a given person on the forum reflect their social position during conventions. Of course, not every member of the community is active on the forum, but still it is one of the most important reference points. This is why topics of the forum can be treated as some vestigial form of discussion about comics which never happened in the 90s. It is a peculiar form of institutionalized criticism, additionally characterized by irony, trolling and lack of discipline: the typical features of Internet forums.

Gildia Komiksu is a source of hermetic jokes and memes understood only among fans of comics. The saying “back of a horse” is an example of such a phrase, as it originates in a 2007 debate on the forum, concerning the role of realist illustration in comics. In a heated discussion one of the participants said that creators of comics try to draw artistically, forgetting about simple things as “drawing a woman’s back properly and making an anatomically correct horse”. That is why some fans ask illustrators to draw them a back of a horse to humorously test their skills.

All such phrases and inside jokes play a huge role in building the community, but for a newcomer it is really hard to get up-to-date with the eleven years of the forum’s activity. New users are treated kindly, but with a distance, typical of close-knitted groups.

4. The community of comics fans nowadays

From the outside, the community of comics fans can be perceived as a heteronomous group keeping very close ties and being reluctant to open up to newcomers. The majority are male representatives of three generations (those raised in the 80s, the 90s and first years of the 21st century), highly diversified, yet able to keep close with each other.

The publication of the comic called Rycerz Ciernistego Krzewu (The Knight of Spiny Shrub), which was a cooperation between a writer, a colorist and many different illustrators, shows that it is hard to join a community of fans. Every two pages of this comics were drawn by a different person but colored by the same one. As a concept it sounded experimental and interesting (even though previously used for example in Grant Morrison’s Invisibles), but the realization was a mess. This comic tried to tell a story of a Polish knight fighting with Teutonic knights, but it failed in every aspect.

The wave of critical reviews was justifiable, but their tone was somehow surprising. The authors were criticized for making bad comics, and the critics’ shared assumption was that the technical problems with mastering the medium were an effect of the creators’ status of outsiders in the fandom community. They were treated as barbarians whose lack of the knowledge of customs makes them unworthy of joining the club.

One of the authors decided to aggressively fight back, which heated the discussion up to the point of full-blown controversy. This conflict shows that the Polish comics fandom tends nowadays to look for enemies to consolidate itself against. For some period manga and anime fans were playing a role of such an enemy, as they are usually female and mostly younger than average fans in the comics community. However, in many cases, people who read manga have been treating it as something essentially different from comics. Not many manga fans read works published in Europe or America. That is why those communities rarely meet, as manga and anime fans organize their own conventions.

Anyway, that particular antagonism is slowly burning out, as more ambitious mangas are being published, attracting the interest of fans of western comics. One of the first manga publishers widely read by both communities was “Hanami,” which specialized in gekiga genre, translating such works as Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto or the works of Jiro Taniguchi. This shows that there are some connections between both fandoms, and that some people move freely from one group to the other.

However, what the conflict with the manga fandom has shown is the existence of a broader problem of the marginalization of women in the comics community, among both fans and creators. Although women who are authors of comics books are not a totally new phenomenon, as confirmed for instance by Szarlota Pawel, one of the most popular creators of comics for children in the communist period, the number of Polish female comics creators has recently been increasing. Two anthologies presenting women creating comics in Poland were printed in 2012: the first one was entitled Polski komiks kobiecy (Polish female comics) and the second one was published in English, as Polish Female Comics – Double Portrait. As an outcome of this project, the editors launched a website Comix Grrrlz , where we can find a database of Polish female creators of comics.

This emancipation of the female perspective in comics and of feminist themes shows that there is a need for an opposition to the mainstream, male dominated market. A lot of the creators who appear in both anthologies have belonged to the fandom for a long time, but the individuality of their voices was never recognized. The importance of these two publications lies in the fact that they have unexpectedly revealed Polish fandom of comics not to be as monolithic and patriarchal as commonly perceived.

One of the attempts to reform the community from the inside is to create an event that would go beyond the frames of typical scenarios for a convention of comics fans. This is one of the main goals of “Centrala” publishing house, the organizer of the International Comics Festival “Ligatura,” which takes place in Poznań. During this annual event “Centrala” is focused mainly on the promotion of alternative comics from the Central and Eastern Europe. As a result of this strategy, not so many internationally recognized stars attend the convention, and its organizers achieve an effect similar to that produced by both anthologies of female comics, i.e. make the community reflect on the essence of Polish comics in relation to their local and geopolitical contexts.

Every year during the festival the question of similarities and differences between countries from the former Soviet Union is approached. As an attempt to tackle this question, every year there is an exhibition launched with an accompanying lecture, workshops and other activities. “Ligatura” is an effective counterpoint to the slightly monotonous formulas of the conventions organized in Warsaw or Łódź. The strategy of stressing the role of alternative comics builds another kind of opposition to the mainstream, which is an important way to open up the Polish fandom to works published in the neighboring countries.

Another interesting attempt to blur the lines within the comics community is Wyjście z Getta (Coming out of the Ghetto) a collection of interviews conducted by Sebastian Frąckiewicz with creators of Polish comics. The starting point of Frąckiewicz’s book is acknowledging the fact that the Polish comics market is a niche, or even a ghetto. During the interviews, the author wonders whether it is possible for the whole community, but especially for the authors, to get out. He does not think that suddenly comics in Poland will become mainstream, but he confronts his interviewees with a notion of connecting two “ghettos,” so to speak, i.e. the comics community and the art world. He postulates putting comics into galleries.

This solution is highly debatable and a little utopian, but still Frąckiewicz manages to make many interesting points. The Polish fandom faced with a perspective of never being part of the mainstream tends to incorporate the role of the victim. In the 80s the role of the antagonist was played by the communist government, and now it has become ascribed to amateurs trying to make comics without proper skills and knowledge. To end this trend, comics fandom has to be constantly faced with other communities and its borders have to be constantly transgressed. It does not matter whether it happens in a confrontation with other communities or with minority groups inside the fandom. The current situation of comics and comics fandom in Poland is fluid. The hierarchical structure has been challenged on many occasions, which allows the community to redefine itself and refresh its own priorities.

Bibliography

Comics Grrrlz – comicsgrrrlz.pl

Esensja – esensja.pl

„Fantastyka” 1/1982 – 6 (93)/1990

„Fantastyka – Komiks” 1/1987 – 1-2 (10-11)/1990

S. Frąckiewicz; Wyjście z Getta. Rozmowy o kulturze komiksowej w Polsce; Warsaw 2012

Gildia Komiksu – komiks.gildia.pl

„Komiks” 1/1990 – 2 (32) / 1995

Komiks w Sieci. Antologia polskiego komiksu internetowego; Cracow 2004

Kontekstowy miks. Przez opowieści graficzne do analizy kultury współczesnej; ed. G. Gajewska, R. Wójcik; Poznań 2011

Ł. Kowalczuk; TM – Semic. Największe komiksowe wydawnictwo lat dziewięćdziesiątych w Polsce; Poznań 2013.

„Nowa Fantastyka” 1/1990 – 4 (367)/2013; fantastyka.pl

M. Parowski, J. Rodek, B. Polch; Klasyka polskiego komiksu #6 - Funky Koval; Warsaw 2002

Polish Female Comics - Double Portrait; Poznań 2012

Polski komiks kobiecy; ed. K. Kuczyńska; Warsaw 2012

Zeszyty Komiksowe – zeszyty komiksowe.org

About the Autors

Michał Jutkiewicz – PhD candidate at the Polish Studies Department of Jagiellonian University, writing his thesis on comics and comics culture on the Internet. Lecturer and an active member of Małopolskie Studio Komiksowe (Małopolska Comics Studio) at Public Library in Cracow, where he conducts regular meetings. One of the organizers of Krakowski Festiwal Komiksu (Cracow’s Comics Festival).

Rafał Kołsut – final year student of Theatre studies at Polish Studies Department on Jagiellonian University. Comic book scriptwriter, collaborating with magazines and annual anthologies such as Ziniol, Triceps, Kolektyw (Collective), Profanum. Pop culture reviewer in KZ – Magazyn Miłośników Komiksu (KZ - Comic Fans Magazine).

[Illustration: Back of the Horse by Robert Sienicki]

MODERATOR -

MODERATOR -  FACILITATOR -

FACILITATOR -

Monica Mendoza is a 20-year-old poet and proud daughter of immigrant parents. An Oakland native, Monica is currently a second-year college student pursuing her undergraduate degree in women’s studies and was most recently featured in the

Monica Mendoza is a 20-year-old poet and proud daughter of immigrant parents. An Oakland native, Monica is currently a second-year college student pursuing her undergraduate degree in women’s studies and was most recently featured in the  FACILITATOR -

FACILITATOR -

Named one of the "25 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World" by the Utne Reader,

Named one of the "25 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World" by the Utne Reader,  Roxana Ayala is currently a senior at the Math Science & Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High school. She is the the Vice President of Magnet and active member Upward Bound, Moviemento Estudantil Chicano/a de Aztlan, and I.AM. USC Mentorship.

Roxana Ayala is currently a senior at the Math Science & Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High school. She is the the Vice President of Magnet and active member Upward Bound, Moviemento Estudantil Chicano/a de Aztlan, and I.AM. USC Mentorship. Uriel Gonzalez is a senior at the Math Science & Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High school. He is the President of the Magnet Academy and currently involved as President of the RHS Bible Club, an Upward Bound member, and a proud GIS advocate.

Uriel Gonzalez is a senior at the Math Science & Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High school. He is the President of the Magnet Academy and currently involved as President of the RHS Bible Club, an Upward Bound member, and a proud GIS advocate. FACILITATOR -

FACILITATOR -

FACILITATOR -

FACILITATOR -