Participatory Poland (Part Five): You Forgot Poland: Exploratory Qualitative Study of Polish SF and Fantasy Fandom

/In the “Participatory Poland” report a group of Polish aca-fen makes a preliminary attempt towards defining the specificity of an Eastern European country’s participatory culture shaped both in the communist and post-communist periods. By placing the development of selected fan-based activities against a broader socio-historical background, we are trying to capture the interplay between the global and the local context of participatory culture, as well as take preliminary steps towards making its Polish branch available for academic research. Thanks to Professor Henry Jenkins’ incredible support, we are able to share the first, though by no means final, results of our investigations with aca-fen worldwide. The posts included in this report deal with several examples of Polish participatory activities, namely, the literary and media fandom of speculative fiction and role-playing games; comics fandom; fandom of manga and anime; historical re-enactment associations; and the prosumerist phenomenon of bra-fitting. While we are planning to continue and expand our research, we hope that its samples presented in this report contribute to the exploration of participatory culture.

You Forgot Poland: Exploratory Qualitative Study of Polish SF and Fantasy Fandom

By Justyna Janik, Joanna Kucharska, Tomasz Z. Majkowski, Joanna Płaszewska, Bartłomiej Schweiger, Piotr Sterczewski, and Piotr Gąsienica-Daniel, Jagiellonian University in Krakow

The analysis presented hereby comes from the recently concluded pilot part of the “Participatory Poland” project. We have carried out a computer-aided qualitative content analysis (applying commonly used guidelines for this kind of research, see Selected Bibliography)on the largest fantasy fandom portal in the country - polter.pl. The analysis included all content published on the site in September 2013. Poltergeist (widely known shortly as Polter) is the largest site of its type, but more importantly, it invites most participation and engagement and of all the fantasy-fandom-related platforms. It also courts the largest number of content created by the users.

Polter became the central hub of fan activity in the early 2000s, after the magazines which had fulfilled such role before – the literary Nowa Fantastyka and the roleplaying games magazine Magia i Miecz - either lost popularity and became more of niche press (NF) or closed down (MiM). Polter fulfills the double role of an informative as well as a social medium, Some of the texts (mostly news on events and recent releases) are published by the editorial staff, but the portal also allows for user contributions, some of which are featured on the main site. The blogs section is well developed and provokes lengthy discussions, offering reviews, roleplaying guides and tips, and articles on a variety of subjects connected with the fandom. Blog submissions are purely amateur and do not require the staff’s preliminary approval although they can be modified or deleted in case of violating the site’s guidelines. Polter has also been one of the first fandom platforms, together with Valkiria (which concentrates largely on games) and Fahrenheit (with a literature focus), and definitely one with the goal to cover all fandom matters.

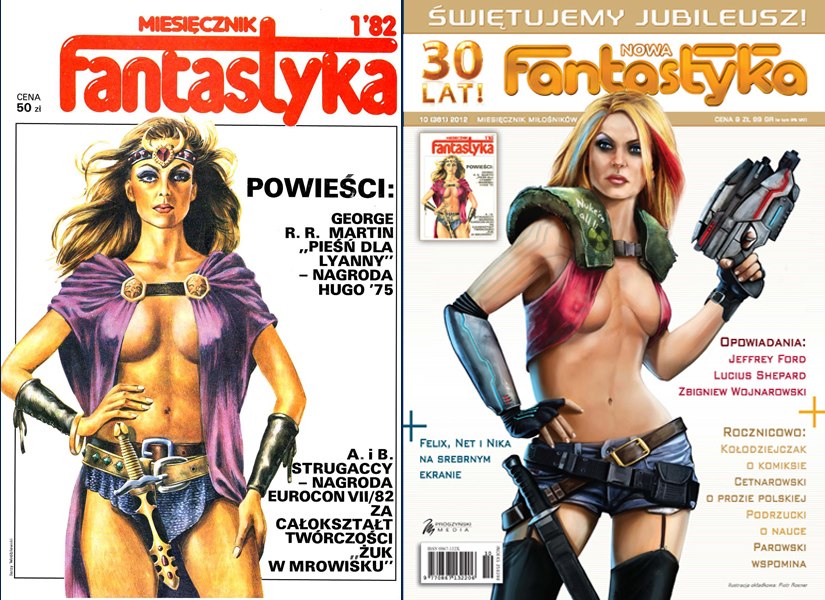

Caption: 30 years of progress? The first cover of Fantastyka magazine and its 30th anniversary rendition (Nowa Fantastyka magazine)

Historically, and to this day, the majority of SF and fantasy fans have concentrated their attention on literature and pen and paper roleplaying games. While genre films, TV series, computer games and other media usually of great interest to fans worldwide still appear in discussions and activities of Polish SF and fantasy fandom, they remain less popular.

Within the genres of tabletop roleplaying games and SF literature, Polish fandom differs from the majority of Western fandoms with its definitions of canon works. The limited access to and the small number of Western media available (mostly via unofficial means and xerox copying) to fans before the political transformation of 1989 has hugely influenced this state. For instance, the system considered as the classic of the Western roleplaying fandom, Dungeons and Dragons, was adopted in Poland with a significant delay and never reached the top popularity although nowadays it is also considered a classic. Instead, the prototype of all the games and still the major point of reference for most players, is the setting of Warhammer (in the 2000s followed by both editions of World of Darkness).

Similarly, when composing the list of the greatest SF and fantasy classics, a typical Polish fan would create a list different from their American or British counterparts. While the works of the authors considered worldwide as absolute classics (such as J. R. R. Tolkien, R. E. Howard, Ursula Le Guin, Frank Herbert, P. K. Dick) still underline the literary canon, they are accompanied by many works from Eastern European writers (such as the Strugatsky brothers or Kir Bulychov) and, maybe most importantly, Polish works which before '89 tended to be heavily influenced by the need to write about the political situation under the guise of SF. This trend of science-fiction prose as a vessel for social, political and sometimes philosophical topics was largely established by Stanisław Lem and Janusz A. Zajdel, whose impact on later fiction is recognizable to this day.

Caption: Kir Bulychov as a guest at a convention organised in a college, 1997. Photo: Szymon Sokół

Fantasy cons and fan gatherings have always been the liveblood of Polish fantasy and SF fandom. Unlike many Western conventions, Polish gatherings are not dominated by discussion panels from academics, aca-fen and media creators, but are instead filled with roleplaying sessions (sometimes announced but often spontaneously arranged) or lecture-like presentations often given by fans who do not study or lecture on the subjects professionally. Cons are usually organised by particular, city- or province-based fan organisations, and everyone who works at them does so voluntarily. Local fan organisations use conventions as a tool for promotion, and the quality of the events is seen as the reflection of the club’s rank and the strength of the local fandom. Such connections with a specific local community are often highlighted in cons’ logos that contain visual motifs associated with certain Polish cities.

Conventions are attended by authors and publishers, but the content producers in attendance are usually connected to the realms of books, comics and roleplaying games, with movie and television producers largely absent. It is worth noting that even the largest conventions (attended by above 10,000 fans) are all run by the fans themselves, without the involvement of any professional event planning companies. The authors in attendance are not compensated for their involvement. Commercial booths accompanying the events, limited to small areas, are not considered a significant feature of a con. The majority of cons are held on weekends, usually in rented classrooms of public schools, and not in conference centers or fairs venues. However, our analysis suggests that fans often formulate demands for the conventions to be organised in a more “professional” manner - this trend becomes noticeable in our material in the comments sections of the posts on a major event, Polcon, infamously nicknamed by the fans in social media as “Kolejkon” (“Queue-con”) because of its organizational issues. Some fans argue that because participants pay for the entry, a con should be considered and evaluated as a product. A commercial standard is being applied to an event run by unpaid volunteers, which marks a certain change of attitude considering the grassroots origins of Polish conventions.

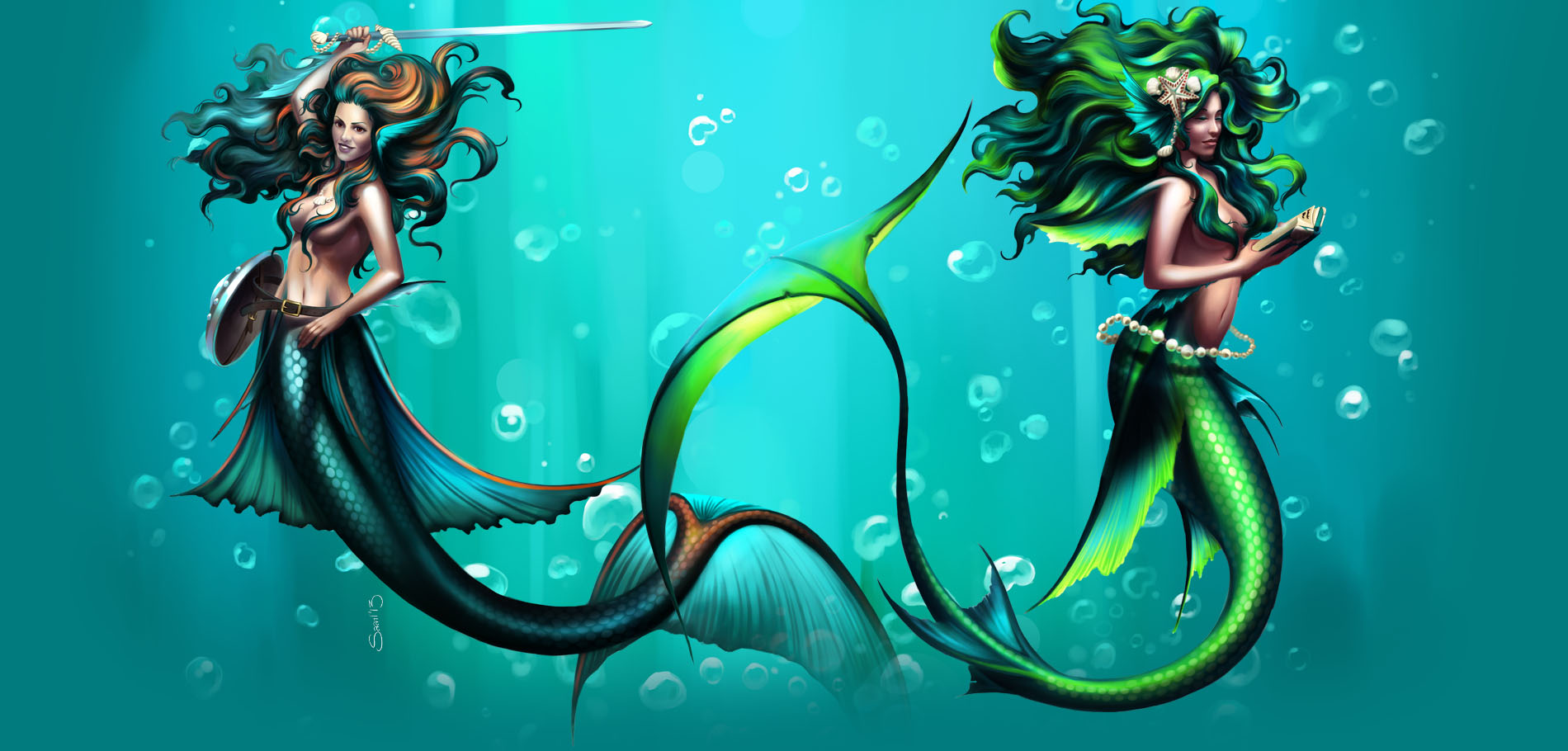

Caption: Polish mermaids are the most beautiful! Local pride expressed in the promotional graphics of Warsaw-based Polcon convention (mermaid is the symbol on Warsaw’s coat of arms). By Sylwia 'Saarl' Smerdel

Furthermore, the most active fans are most appreciated by their colleagues and such participation and productivity are important criteria in fandom’s internal stratification. Professional book writers hold the biggest prestige among the community, followed by creators of other media (for instance game designers have a lower status than authors of literature) and active fans (where participation in events and local gatherings is valued higher than online-only activity). These distinctions are also reflected in convention programmes: institutionally recognized contributors (such as book authors or academics) invited by the organisers have a status of “guests,” whereas those who volunteer to give presentations or run other events are called “programme creators” and have a lower status than “guests.”

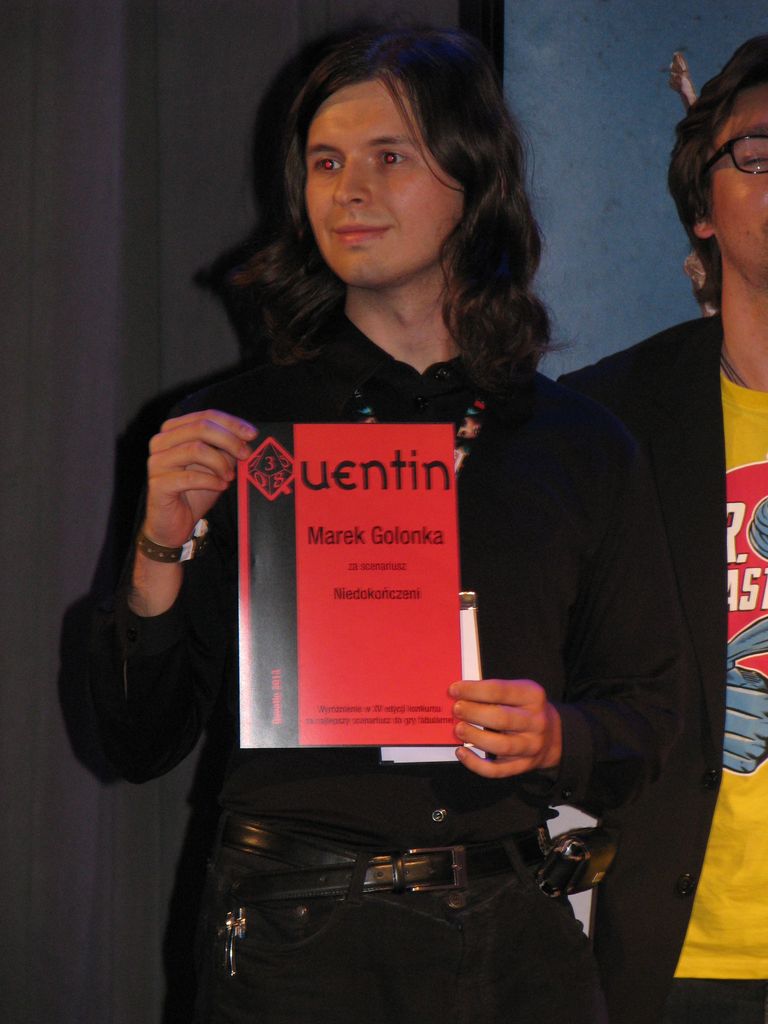

Conventions become hosts to most important awards within fandom, starting with the Hugo-inspired literary award Zajdel (or: Nagroda Fandomu Polskiego im. Janusza Zajdla), through such honors as PMM (Puchar Mistrza Mistrzów - the Cup of the Masters' Master), a competition for the title of the best Game Master, and Quentin, atrophy given to the author of the best roleplaying scenario. These are not the only honors awarded within the fandom, but they are also best known and as such, most discussed and disputed.

Caption: A statuette of Janusz Zajdel Polish Fandom Award, a Hugo-based literary prize. Photo: Szymon Sokół

These are just some of the subjects fervently discussed on Polter and became the subject of our analysis in this study. All of the items published in September were copied together with accompanying comments into a program aiding in content analysis. With its help, the posts were sorted according to the site’s division into news, reviews, articles, blog posts, etc. Next, they were coded with a codebook established earlier for the purpose of this research. Coding categories were modified during the course of research in order to make them more suited for the encountered data. The categories were devoted to the forms of communication between the users, especially to the internal links between comments and the references made to various cultural texts. Also, specific categories were established to examine the various criteria of validation used by the fans in relation to commented media or events, textual strategies of justifying their opinions, and discursive ways of forming fans’ identities (inclusion and exclusion of certain content and groups).

It is important to hold in mind the exploratory character of the analysis, the results of which are by no means finite or final, but rather outline the field of study and constitute the basis for the research questions we will be tackling. This initial analysis set out to discover the most interesting content and processes in the contemporary Polish fandom. The following stages of the project will include data from a number of other sites sharing a similar profile. Due to the significantly low number of fandom-devoted portals in Poland, we can include all of them in our analysis. We are also planning to extend our research to some of the most interesting topics arisen during the initial analysis, as well as to turn to researching the participants themselves, that is the fans.

During the researched month, close to five hundred items were posted to Polter. Within those, books get the most coverage among all the media, while? news about recent releases and reviews form the largest group of content published by the editorial staff. However, our study showed that it is the content connected to games (mostly pen and paper RPGs, but also videogames) that generates most social engagement. Roleplaying games seem to be the center of attention of Polter’s community; fans eagerly comment not only on the news and reviews of player’s guides, add-ons etc., but also on users’ submissions, such as scenarios, reviews thereof and session reports. The extent of these participatory mechanisms can be well observed in the case of Quentin, the annual contest for the best roleplaying scenario, established in 1999 and hosted by Polter since 2003. All submissions for the contest are published on the website. The scenarios are evaluated by an independent committee and the winning work is posted on Polter, but users’ activity related to the contest entries does not stop after the verdict is announced and many of the texts concerning Quentin are user-created.

Caption: Quentin award for the author of the best role-playing scenario. Photo: Szymon Sokół

The case of Quentin-related engagement is also an example of another wider trend. Our study showed that most of the interactions within the Polter community, as well as the comments on the works, are positive. Polter users express appreciation more often than dissatisfaction, and the criticism of other users’ content is usually constructive. This leads us to an assumption that mutual support and quality of content published on Polter are important values for this community and that fan identity is created and maintained through positive rather than negative expression (we elaborate on matters of inclusion and exclusion later in the text). This observation somewhat contradicts the widespread stereotype of a malcontent fan who uses online media mostly to express dissatisfaction and engage in conflict; the stereotype also held by the fans themselves, who seem to perceive the community as largely negative.

Our study paid a significant attention to the strategies of developing fan identity, through interactions and tactics of inclusion and exclusion. A part of this identity is forged through reading and media consumption habits presented publicly. As noted before, the majority of news posted on the website were connected with book releases, despite the fact that the most heated discussions were related to game posts and blogs. While most fans participate in several areas of media consumption and fan activities, SF and fantasy novels are perceived as much more high-brow than gaming. A fandom portal such as Poltergeist, while catering to the needs of all kinds of fans, makes a claim to a professional status by showcasing book releases and publishing book reviews. Similarly, fans attempt to raise their fandom status by disclosing their reading habits; the more books read the better, and the quantity is just as important as the quality of the works.

While the status of ‘having read’ the classics is important to a fan’s social standing and the familiarity with well-known works is desired, fans also have a tendency of distancing themselves from everything and everyone that has ‘sold themselves out’ and became irreversibly commercialised and therefore tainted by the mainstream association, becoming somehow less connected to fandom. This tendency features both in the case of actual commercial properties that have acquired a greater renown and in the case of fandom participants who have forged their fan activities into a source of income. Such cases are often treated with distrust or derision.

Caption: Growing popularity of steampunk and cosplay: Mad Artistians' stand at Falkon 2013. Photo: Falkon 2013

Another topic connected with identities included in our research is the ways Polter users conceptualize and discursively create the boundaries of fandom and its subcommunities. While there is a widespread use of the general term “the fandom,” incorporating all fans and topics of SF & fantasy regardless of the division into particular media and subgenres (and the Polter website sections also support this generalizing attitude), the self-identification practices of fans are more nuanced. Several times in the source material we encountered opinions about specific interest groups within the fandom that perceive themselves as autonomous and hardly want to communicate with each other - this was said about fans of LARPs, manga & anime, videogames and comic books. Manga & anime fandom seems to be especially stereotyped and more often than not placed outside the boundaries of SF and fantasy community; mentions of it in the source material often provoke the commenters to talk about “fandoms” (in plural). A similar case of a fandom splintering can be seen in the case of the Western comics fandom, but while the comic books fan seem content with standing apart from ‘the fandom’ of SF and fantasy, manga and anime fans strive for inclusion and recognition, especially on the local level of conventions and events. Their attempts are sometimes met with resistance, such as exclusion of manga and anime subjects from the convention programmes by the organisers. It is worth noting that the manga and anime fandom is relatively younger and much more feminised than the SF and fantasy fandom, and has been introduced in Poland fairly recently in comparison with others (more on this topic in an upcoming part of the report, devoted specifically to the manga & anime fandom).

Our findings also point out that patriotism is a vital component of Polish fans’ identity. This phenomenon can be observed on several levels. The most apparent is that the fans are eager to include, or even ‘adopt’ works or authors who seem even marginally connected to Poland. While in general, works most often consumed and discussed come from abroad rather than from Poland (with the exception of cult writers such as Lem or Sapkowski), the national pride and patriotism seems to be awakened by mentions of Poland and Polish matters in foreign works. This tendency has been illustrated during the analysed period in the instance of the new novel (Forest Ghost) from Graham Masterton, who set his story in Poland. Masterton himself accentuates his Polish connections and his new novel had been published in Poland even before its debut in the UK. Another example of clear national pride is displayed when a Polish work enjoys success abroad (in recent years it has especially been the case with game developers, most notably the creators of The Witcher series) as fans consider themselves to be a part of that success.

Caption: Agents of F.I.E.L.D.? Promotional graphics of the expansion Conspirators for the Veto! collectible card game about the Polish noblemen from the 17th century. Spoof of The Avengers movie poster. By Igor Myszkiewicz and Maciej Zasowski

On a more general level, SF & fantasy fans seem to share and reproduce the vision of patriotism grounded in the Polish 19th-century Romanticism, with its focus on national history, the values of chivalry, fight for a just cause and an idealised view of love and femininity. This can be well-observed in the case of fans’ attitude to history. Historical narratives (also those incorporating SF & fantasy elements) are being evaluated with the use of ideologized notions of “scholarly validity” and “historical accuracy,” accompanied by a belief in the possibility of access to the truth about certain events and phenomena. Historical references are used to maintain the national pride (hence the popularity of novels set in the “Sarmatian” period of Polish history regarded as the highest point of national splendour), but also tend to be connected with practices of exclusion - for example, the presence of female warriors (or women in positions of strength in general) is disregarded as historically implausible.

Caption: Practically Polish. Graham Masterton (on the right) socializing with Polish fans at a convention. Photo: Geekozaur

On the other hand, our study found some instances of views that are more critical to the mainstream Polish views on patriotism. The anticlericalism and pagan inspirations attempt to challenge the usual affirmative approach to Christianity and its cultural role. An informative discussion occurred in the comments on a Polish card game about the Polish military fighting with the Taliban in Afghanistan. Whereas the reviewer appreciated a Poland-related theme, there were also opinions criticizing the game for allowing players to choose the Taliban side (and fight against the Polish), and also for depicting colonial violence. The discussion thread shows the clash between the conflicting views on Polish patriotism: the same work can be viewed in terms of continuing the honorable tradition of fighting for freedom or criticised as promoting Polish participation in imperial oppression.

Another aspect of declared patriotism is connected to consumer choices. As stated before, the media discussed and referred to on Polter are predominantly Western, mostly originating from English-speaking countries. However, there is a very distinct declarative tendency to ’support the Polish market‘ (both discursively and financially). The market of Polish SF & fantasy products (especially RPG-related) is perceived as small and constantly endangered by financial hardships. It is worth noting that certain dissatisfaction with the quality of Polish works or editions/translations does not stop these slightly patronizing general appeals to support the local media and creators.

Within the identity-related categories in our study we also established one connected to direct and indirect statements about gender. Though it is by no means a dominant issue for Polter users, it is still possible to notice some general tendencies. In a few instances the site’s participants suggested and tried to diagnose some inherently and inescapably specific ways women engage in certain activities, such as playing pen & paper RPGs or writing books. Female physical attractiveness is commonly perceived as a valuable asset in various contexts, from evaluation of drawn fanarts through comments on female cosplayers on conventions. It is worth noting that we found very few statements about masculinity in the source material; generally, only women are objects of generalizing statements, which suggests that a male fan is recognized as a default member of the community and a female fan is a special phenomenon that requires examination. Historically, Polish SF and fantasy fandom has always been rather male-dominated, with a prevailing belief in the old chestnut that all gaming women are girlfriends of the game masters. However, in the middle of the 2000s, the numbers of female representation in the fandom surged significantly. The last few years brought on the attempts to form a female fan (and especially a female roleplayer) identity. These attempts in turn sometimes meet with negativity from the more conservative fans trying to neutralise such emancipatory tendencies by generalizing statements along the lines of “fandom is not for women, fandom is for everyone.” At the same time, splinter fandoms of manga and anime or fanfiction writers tend to be much younger and female-dominated, and gender roles are often very different from the ones taken for granted by the majority of the SF and fantasy fans.

Caption: ‘Mom, can I exterminate already?’ A young female Dalek at a convention. Photo: Szymon Sokół

To sum up, in our exploratory research of Polish science-fiction & fantasy fandom we found the following problems to be the most interesting and worth further examination (possibly with an inclusion of diachronic longitudinal methods and different media outlets):

1) Fans’ attitudes towards national categories and notions of Polish identity. Divergent tendencies were observed in that area: on one hand, most of the fans seem to share conservative, affirmative views on Polish history and identity, with a distinct tone of national pride; they seek and appreciate topics related to Poland in foreign works and declare interest in and care about Polish SF & fantasy media despite being aware of the flaws and limitations of this market. On the other hand, the study showed that fans refer mostly to works of Western origin in their texts, comments and practices, which suggests that there is a constant process of negotiation between joining global cultural trends and maintaining local specificity; also, some more revisionist and critical attitudes towards the dominant discourse of Polish national identity start to appear. Still, references to national categories are vital points in fan discussions, even if treated negatively.

2) Gender views remain on the conservative side, with a prevailing tendency to see the masculine as the default. However, in the recent years a rising trend of female fans and players attempting to define their own identity has appeared. Such attempts are often opposed to on the grounds that they represent ‘special interests’ and are not pertinent to the group as a whole. Some female fans differentiate themselves from the whole of fandom either by adopting a unique style (of playing, of writing, of attire) or by finding niche activities to make their own, i.e. fanfiction or forms of expression relating to costuming (cosplay, steampunk, etc.), while others openly demand more diversity within the fandom’s mainstream. As the demographics of fandom changed significantly in the past few decades, we can expect the trend of female fans making themselves more visible and aiming for recognition to rise in the future.

3) There are increasing voices calling for a professional approach to previously grassroots initiatives of SF and fantasy conventions. Historically, the events were organised by volunteers and local organisations and were perceived as a communal effort, while nowadays some of the convention-goers point out that the cons should be treated in terms of a commercial product and therefore give the participants the right to demand a much more professional approach. At the same time, other tensions between the amateur and professional realms emerge, presenting contradicting views: the fans want Polish works to succeed locally and internationally, but are distrustful of anything they consider too commercial or mainstream, bringing forth the accusations of “selling out”.

4) Tensions appear also in the area of media consumption. While most fans are ascribing prestige and nobility to literature, especially the more high-brow and canon works, and are eager to boast about their reading history, they tend to engage more with the works of a perceived lesser status, such as pen and paper roleplaying games.

We believe that our exploratory study of Poltergeist community can lead to deeper diagnoses of the specificity of participatory culture inside the SF & fantasy fandom in Poland and forms a strong starting point for further research.

Selected Bibliography

Cappella J.N. et al. (2009). “Coding Instructions: An Example.” In Krippendorff K., Bock M.A. (Eds.), The Content Analysis Reader (pp. 253-265).Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Carvajal, D. (2002). “The Artisan's Tools. Critical Issues When Teaching and Learning CAQDAS.” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research 3(2). doi: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-02/2-02carvajal-e.htm

Hak T., Bernts T. (2009). “Coder Training: Explicit Instructions and Implicit Socialization.” In Krippendorff K., Bock M.A. (Eds.), The Content Analysis Reader (pp. 220-233). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

MacQeuun K. et al. (2009). “Codebook Development for Team - Based Qualitative Analysis.” In Krippendorff K., Bock M.A. (Eds.), The Content Analysis Reader (pp. 211-219). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mayring P. (2000). “Qualitative content analysis.” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research 1(2). doi: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089

About the Authors

Justyna Janik: MAs in Comparative Studies of Civilizations and Cultural Anthropology, PhD student in the Institute of Audiovisual Arts, interested in game studies and pop culture theory, especially fan studies;

Joanna Kucharska: MAs in English Literature and American Studies, PhD candidate at the Institute of Audiovisual Arts, researching audience participation and transmedia

Tomasz Z. Majkowski: Aca-fan, PhD in Literary Criticism, Assistant Professor at Department of Literary Anthropology and Cultural Studies at the Faculty of Polish Studies of Jagiellonian University, interested in pop culture theory, especially fantasy and sci-fi studies, game studies and historical interactions between pop culture and ideologies.

Joanna Płaszewska: Slavic philologist, librarianship and information science student, interested in fanfiction readership and new literacies.

Bartłomiej Schweiger: PhD student in Institute of Sociology on Jagiellonian University, interested in power-knowledge structures embedded in our culture, especially videogames.

Piotr Sterczewski: MA in Cultural Anthropology, PhD student in the Institute of Audiovisual Arts (Jagiellonian University), interested mostly in ideological aspects of videogames.

Piotr Gąsienica-Daniel: Sociologist and researcher at TNS Poland