'Less is Moore: Alan Moore's 2000AD Short Stories,' Andrew Edwards (Part 1 of 2)

/British comics have been dominated by the anthology format throughout their history. Theirs is an origin that runs parallel with American comics, up to a certain point, in that titles like Action Comics and Detective Comics were originally anthology titles. However, each issue would later become dominated by stories featuring one character, such as Superman in Action Comics and Batman in Detective Comics, in a number of short adventures, before their final evolution into one story per issue and, ultimately, multi-part serialised adventures. British comics never made that leap into character dominated titles. Variety served as the fuel that powered titles like the Dandy and Beano, Eagle and Hotspur, Action and 2000AD to greatness. Only the Beano and 2000AD have survived the cull of titles in the local newsagent, although this is mitigated by the strong showing independent comics have made in this country in recent years.

In terms of 2000AD, characters that match their American peers in terms of inventiveness and appeal abound. This is the title that brought us Judge Dredd, Strontium Dog, Halo Jones and dozens more. No doubt its nature as an anthology has led to its longevity; even through fallow periods, there is always another serial ready in the wings to potentially engage, amaze or astound us. Yet beyond the main attractions, or star turns, of 2000AD exist the ‘Future Shocks’ and ‘Time Twisters’, which are short, twist ending stories. They were conceived as being very much in the style of Twilight Zone or Outer Limits episodes. This format was first used by Steve Moore with his story ‘King of the World’ (in issue, or ‘Prog’ 25, 25th August 1977). They came to be the training ground of numerous British writers who went on to more visible work both in the UK and USA, none more so than Alan Moore, who wrote over 50 of stories. These stories saw him gain experience of writing short narratives at a greater length than his early cartoons for Sounds, and enabled him to undertake early experiments with the form of comics and genre expectations. The remainder of this article discusses a representative selection of these works to give you an indication of Moore’s early achievements in this context.

One early experimental piece, ‘The English/Phlondrutian Phrasebook’ (Prog 214, 30th May 1981) plays with the format of the comic page by suggesting a futuristic handheld electronic language guide, with four screens that effectively constitute four panels of the comic page, ably designed by artist Brendan McCarthy.

The story, published in 1981, pre-empts hand held computing devices: indeed, the function keys resemble those to be found on tape recorders of the period (see bottom right of the above page); perhaps another potential influence could be the hand held guide that features in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Here, experimenting with the visual form of the comic page serves to reflect the futuristic content on the story.

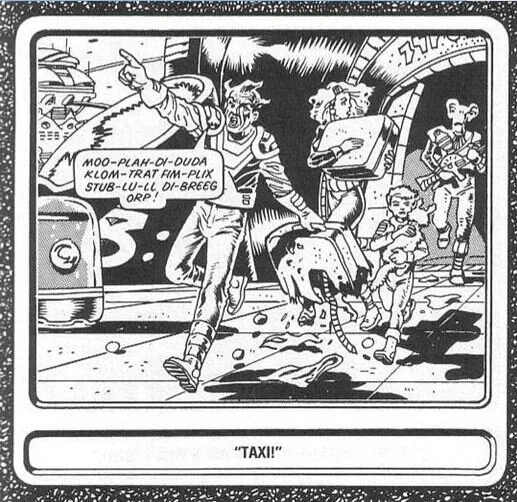

The relationship between words and images reveals two types of interactions, where meaning is either co-dependent or independent. The full meaning of this panel is dependent on both the words and images.

The image consists of a family running and being pursued by an alien. The word used – ‘Taxi’ – indicates that the man is hailing a taxi, rather than another interpretation of why he is holding out is right arm. Words and images are combined completes the whole meaning of the panel. In Understanding Comics (1994), Scott McCloud’s theory of the relationship between words and images in comics is helpful here, specifically the ‘Interdependent’ combination that he identifies, ‘where words and images go hand in hand to convey an idea that neither could convey alone’. Moore’s text serves as a counterpoint or ‘anchor’ to the action depicted in the panel. This is a precursor to the kind of effects he continued to develop in work like Watchmen, where he would juxtapose text with visual images to create more nuanced interdependent meanings, where dialogue from one scene anchors the visual detail in another, or extracts from ‘Tales of the Black Freighter’ offer an ironic commentary on the main narrative.

Historically, the use of words and images has sometimes been repetitive in comics, in the sense that the former merely repeated the content of the latter in what McCloud calls ‘Duo-specific panels’ in which both words and pictures send essentially the same message:

Moore is not averse to using duo-specific panels. In ‘A Cautionary Fable’ (Prog 240, 28th November 1981). Moore and artist Paul Neary draw on this method in the creation of a story that draws stylistic inspiration from early 20th century comics, in addition to illustrated stories and film.

The story features Timothy Tate, a child whose appetite reaches monstrous and unreal proportions during the course of the story. Duo-specific panels dominate the story in order to replicate the features of older children’s comics and children’s illustrated stories, where images and words contained the same meaning and the use of Interdependent panels would have worked against this and led to a less effective homage.

Moore and Neary produced accomplished pastiches in terms of the respective poetry and illustration used in this story. Moore maintains the strict metre and rhyming scheme required of this type of tale. Neary’s illustrations locate the story within the early twentieth century in terms of fashion styles. This is underscored by the reference to King Kong.

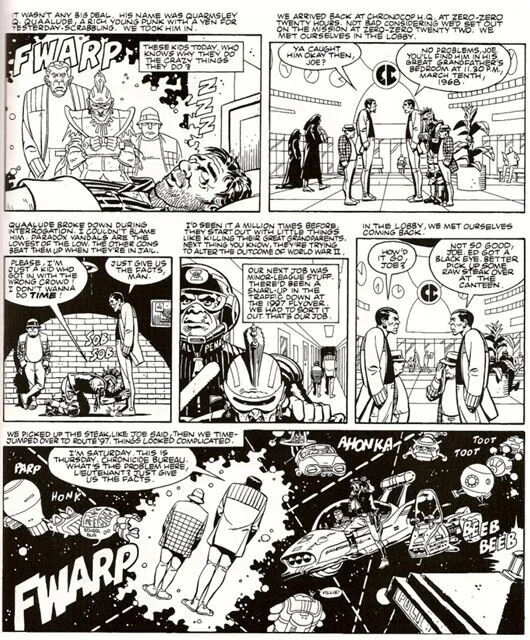

Such media knowledge and literacy is also evident in ‘Chronocops’ (Prog 310, 2nd April 1983), where Moore and artist Dave Gibbons combine a Dragnet inspired police procedural story with time travel, leading to some innovative experiments with time and the construction of comic panels within the story. Its comedic tone and science fiction subject matter also betrays the influence of EC comics, the publishers responsible for MAD and a number of seminal horror and science fiction comics. This influence is boldly signalled with a distinct variation on EC logo in the story.

In order to analyse Moore and Gibbons’ use of panels to reflect time travel it is beneficial to isolate specific panels from their pages. This panel establishes the first of two scenes in the same location that are returned to throughout the story.

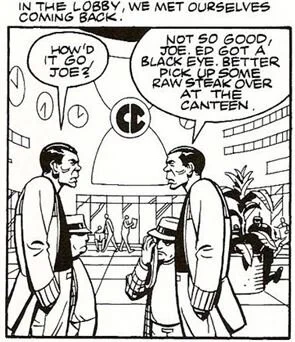

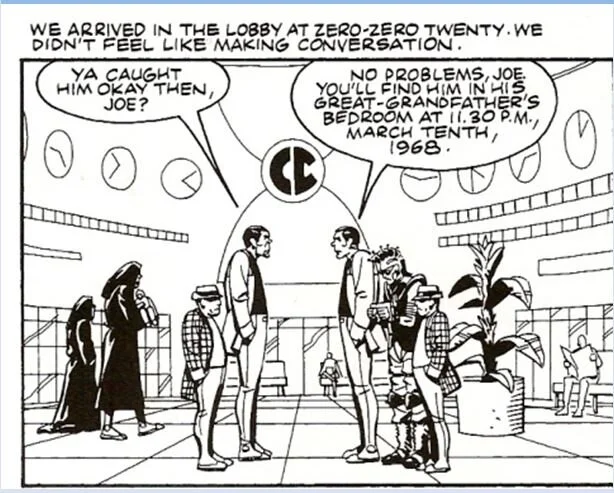

Prior to this, cops Joe Saturday and Ed Thursday are have arrested Quarmsley Q. Quaalude for the attempted murder of his own great-grandfather. This panel depicts their arrival at Chronocop H.Q. two hours before they left, and meet the two hours’ past versions of themselves on their way to make the same arrest.

In this panel, both characters meet future versions of themselves, from later in the story, and discover that Ed has a black eye:.

Prior to the next significant panel, we see Ed receive the black eye, and so we now experience the moment from this perspective – having now reached that point in the story which was previously set in the future.

These panels, while chronologically in sequence, are located and interspersed with other scenes and panels.

However, further complications ensue later in the story, when the characters have to revisit the scene and, to avoid further confusion, hide behind a plotted palm.

Observant readers, upon reading the story and checking the previous panels, will now be able to notice the significance of the figures in the plant pot that existed almost subliminally in the background beforehand. Finally, in the events leading up to this next panel, Joe and Ed are disguised as nuns, who we then see walking in the background of the panel and who take on the narrative at this point:

When comparing this to the same scene depicted earlier in the story, the background presence of the nuns is now much more significant and relevant to the story in the hindsight we gain from finishing reading it. This innovative approach is even more interesting when the visual content of each panel is consciously observed: Moore and Gibbons have merely repeated two panels in order to accurately convey the sense that the same moment in time is being revisited by different temporal manifestations of the same characters. This is neatly underscored by minute attention to detail: no feature is altered, and even the time on the clocks on the wall in the background are consistent. Beyond this, the meaning of the panels, in the way they occupy a particular stage in the narrative that is unfolding as the reader reads, is altered through the text that accompanies them.

‘Chronocops’ effectively demands that you read it backwards and forwards to truly appreciate such effects. It also illustrates an usual and beneficial characteristic of the comic book medium is that you can control the direction and speed of your reading quite easily, either when prompted to do like in ‘Chronocops’, or whenever you want to do something like double-check a previous story point, remind yourself of a character’s name and so on. In this, comic books are akin to prose. For a medium like film, until comparatively recently it was not possible to manipulate the flow of experience in such a way, in that a viewer was locked into experiencing a film at the rate of 24 frames per second, in a forward moving, linear chronological sequence of time, one second to the next and so on. This barrier has somewhat eroded in recent years: first, by the advent of home videotape, which enabled some movement back and forth through a film text, albeit it at a pace limited to the rewind and fast forward speeds of the Video Cassette Recorder (VCR); secondly, by the more advanced digital technologies that began with Digital Versatile Discs (DVDs) and continues with Blu-ray discs, which increases a viewer’s ability to navigate their way back and forth through a text. Such formal experimentation in this story foreshadows similar experiments with time and narrative that we later see in relation to Dr Manhattan’s relationship with time in Watchmen #4.

Andrew Edwards is a comics scholar and writer. His research interests include comics and graphic novels, science fiction, horror, intertextuality, and representations of gender. He gained his PhD in intertextuality and gender in the work of Alan Moore in 2018 at Wrexham Glyndwr University, where he also works as an Academic Skills Tutor. He is currently writing a book about Moore, Bissette, Totleben and Veitch’s Swamp Thing for Sequart. He can be followed on Twitter: @AndrewEdwards88