Remembering UK Comics: An Interview with Martin Barker (Part 2 of 2)

/Q: You said that you had once intended to produce a social history of The Beano. What is it about The Beano that is worth exploring further in an academic context?

Ah, the Beano. Possibly the most successful British comic of all time, sadly now just a husk of what it once way. Formulaic – but what a formula! So damned inventive in its simple, short, repetitive story-lines with wickedly funny characters. Who doesn’t love Minnie the Minx, or the Bash Street Kids? For a number of years I gathered all kinds of materials, including sample issues from all its decades, references to it, interviews with writers and artists (I remember with deep affection my meetings with Leo Baxendale). But it was beyond me. I should have known that I never really didn’t have the skills or the time to do this. I think there is something really interesting about the way the Beano found its métier and format the height of the changes in schools in the UK in relation to class, in the 1950/1960s. I can’t now recall in sufficient detail how I thought this might go, but there was something about a confluence of influences – the puritanism+market instinct of D C Thomson, its publishers, the changes in schooling and relations of kids to parents and authority – which found expression in the comic, its characters and their storylines. Sad to say, it is another of quite a long list of things that I have wondered about doing, across my researching years, but it ain’t going to be done by me, now.

Q: Although you do not identify as a fan, or aca-fan, of comic books, you energetically argue that you “live in this damned country at this damned time and comics are part of my and my children’s lives. And I now say this passionately: let us have as many of the things as we possibly can. In the face of the capital-calculating machine called Thatcherism which uses morality like murderers use shotguns, all the little things like comics matter.” Although written in the context of 1980s Britain, can you expand further on this rhetorical framing?

‘Imagination’ is to me a really important term, but it doesn’t have a great history, as something to be thought about. I remember someone – I can’t remember who, to be honest – pointing out the different ways people tend to gesture when they use the words ‘imagination’, and ‘fantasy’. With ‘imagination’, hands tend to go up and wave animatedly in the air, as though something light and breezy was being welcomed. With ‘fantasy’, chins go down slightly as though something heavy and slightly disreputable was being named. Nowadays this shows in the ways in which the arts (what Lynn Conner calls ‘high value arts’ …) are sought, praised, encouraged, studied, compared to the ways – even now – that popular media materials are considered. I have wanted to reclaim the ways many kinds of cultural materials can help us conceive and wish beyond ourselves and our present circumstances. I remember the expression used by one young woman whom I ‘interviewed’ (it was done at a distance, by a posted tape recording, way back in the 1980s), who said that her comics were important to her because they ‘let you see how far you could see’. I absolutely love the openness of that phrasing. You are right, I did write that in the 1980s – as part of the Afterword to my big Comics and Ideology book. I must confess I wrote that in a hurry, at the explicit behest of my publisher, who felt the book lacked an ending. I am not disavowing it at all, by saying that. But it needs expanding, and in a sense I think a lot of the work I have done since, on audiences for various kinds of ‘fantasy’ is that expansion. Perhaps the thing I have done that is most directly in line with it, is the essay I did out of the pornresearch project, on the ‘problems’ of sexual fantasies (it appeared in Porn Studies in 2013). ‘Imagination’ and ‘fantasy come trailing debates, in ways that impede real research.

Q: What first drew you to the medium as an analyst?

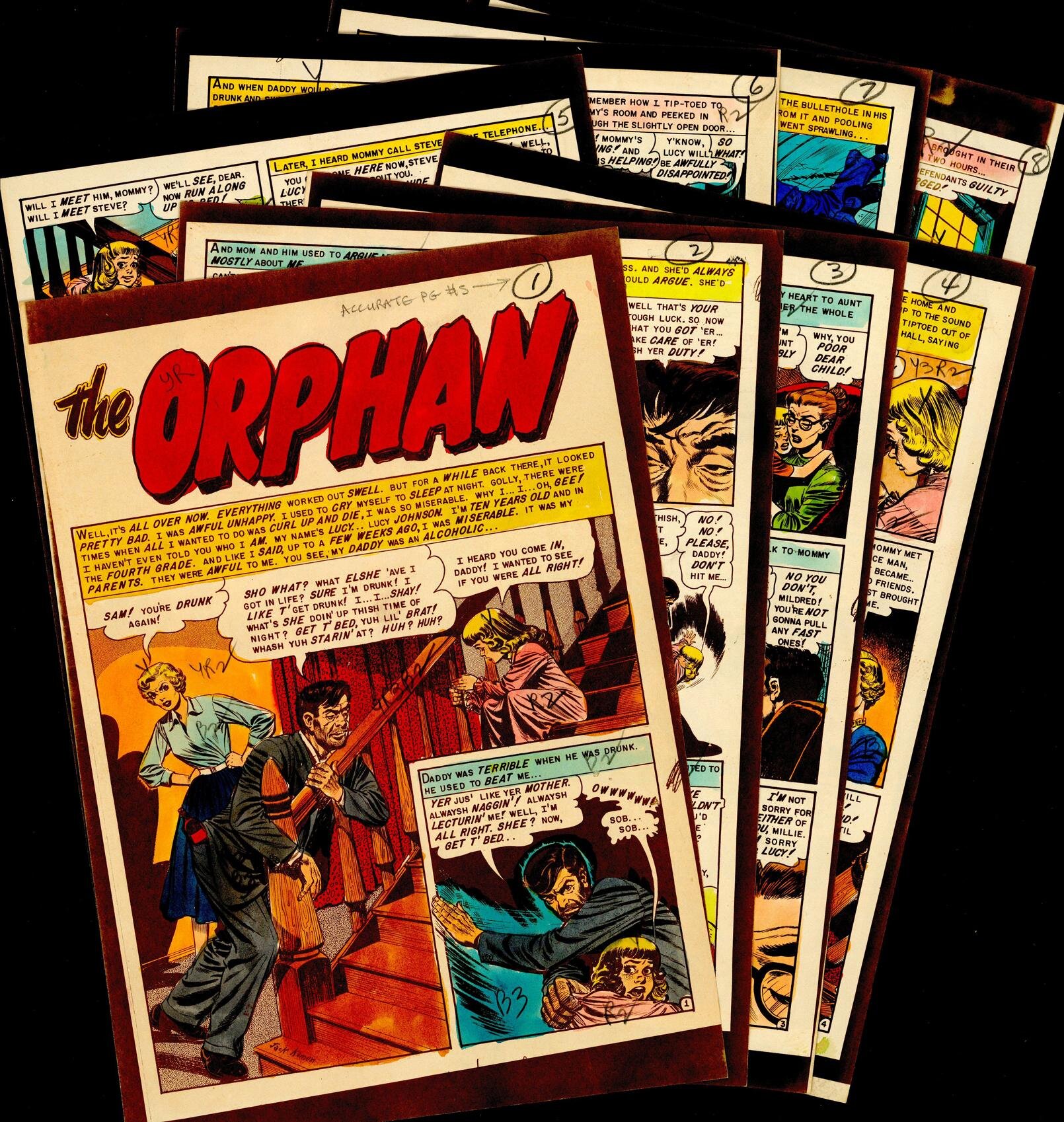

Irena C*****a. It’s all her fault. She was a final year student at Bristol Polytechnic (around 1981/2), who asked if she could do her dissertation on Superman, using Carl Jung as her implement. Of course she could – though it struck me as a pretty arbitrary choice of ‘theorist’. But I had no idea how to supervise her. So I went to the library and searched the (then card-index) catalogue, to see what I could find to help frame her work. There was almost nothing. But one thing, one small pamphlet, caught my eye. It was by someone called George Pumphrey, entitled Comics and Your Children (published by the Comics Campaign Council in 1954). And it talked about a ‘horror comics campaign’. I was of course a child of that period, but had never heard of anything like this. So, a streak of sheer bloody-mindedness took hold of me, and I decided I would try to find out what this thing was that my parents – who were brilliant and lovely people, but very traditional – had shielded me from even knowing about. I was also inclined against and distrustful of censorship, but without having thought deeply about it – I had lived through the campaigns to abolish censorship of theatre, and the struggles over D H Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley. So, I went into the task of (a) trying to uncover what had happened in the campaign, and (b) gathering and looking at some of the comics concerned, to try to make sense of this ‘missed’ period of my childhood. I have to say that comics are not a medium that I respond that strongly to, until, that is, I have a reason to examine them closely. Then, I begin to appreciate their shape and complexity. But it doesn’t come to me naturally. So, I had a lot of fun analysing in detail ‘The Orphan’, that infamous story from 1953 that Jack Kamen drew. But had I not had a motive for studying it closely, I doubt it would have lingered long in front of me.

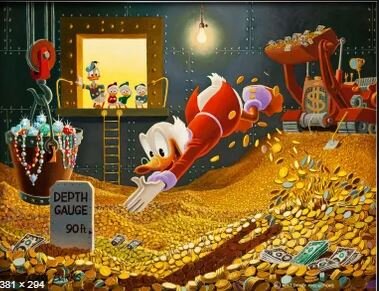

Q: Many scholars have casually—and perhaps lazily—accused Disney of being an ideological factory dealing in suspect material that potentially colonizes the minds of children with racist and gendered stereotypes, thus skewing their image of the world in reactionary terms. As you have stated in an analysis of Donald Duck comics: “Children’s literature has become the prime centre for the ideology of American capitalism […] there can be no more effective form of propaganda than wholesomeness. If anyone attacking it can be branded as ‘anti-children’, you have the perfect device. This is Disney, to the T” (1989, 279, 280). Can you expand on your thinking here? What do you think of the so-called ‘cultural imperialism’ argument? What is it about the figure of the child that dominated moral discourses of this type?

Let’s be clear, first – in that quotation I was trying to summarise a view that I don’t hold to, but which I feel is strongly and widely (and influentially) held. And around that time, the concept of ‘cultural imperialism’ was a site of a lot of debates. Though I haven’t followed the debates closely since, I think it is clear that the high tide of those debates has passed. There are now several books entitled ‘Beyond Cultural Imperialism’ or ‘After Cultural Imperialism’. The concept was intended to provide a lens through which to see ways in which internationally dominant countries – of course, notably the USA – might importantly sustain their domination through the importation and normalization of their own cultural patterns. Stories (films, books, comics, etc) were identified as means by which this might be done. I wasn’t convinced, even though I could feel the strong pull and argumentative conviction of Dorfman and Mattelart’s key book How To Read Donald Duck (produced in Chile not many years before the real American domination – a CIA-backed coup, led by General Pinochet). The irony is that the work which I most drew on was the wonderful work of David Kunzle, who researched and told the history of the ‘good artist’ who produced the great bulk of the Disney Comics stories, Carl Barks – and David was content to use the term ‘imperialism’. Looking at the comics themselves (and without the benefit of anything approaching reception evidence or audience research), I became convinced that, textually, they showed the influence of two competing fascinations: a love of money for its own sake, and a fear of power and chaos. There was also of course the issue of humour – does it work to make Disney ‘innocent’, does it modify the message, does it satirise and undermine? At that time, it was a tiny research area. Now, it is a big area within media and cultural studies, and I don’t have a clue how my ideas from that time would stand up to consideration from the much enriched field as it is now.

Q: In much of your work, the concept of ideology is centre-stage. What are your thoughts on ideological analysis conducted without speaking to audiences? How does your ‘dialogical approach to ideology’ attempt to re-situate the argument, and why did you think it was necessary?

You must understand first of all that the period I tackled this was a kind of high water mark of attempts to theorise and research the concept of ‘ideology’. Dozens of books were written about the concept – and even one or two important empirical studies (I am thinking nostalgically about the Dominant Ideology Thesis, and the work of several brilliant social historians). There were endless disquisitions about the place of ‘ideology’ within Marx’s theory. The concept reverberated with important anti-colonialist movements. By the end of the 1980s, however, the term was largely being dropped, replaced by the softer/looser, less demanding ‘discourse’ – which then easily pluralised into ‘discourses’.

But at the time, it felt important to think how one might formulate a conception of ideology that didn’t ignore questions of evidence about ‘influence’ (in some versions, ‘ideology’ was the left-wing version of the ‘effects’ tradition). And I tried to do this, through a long struggle with the ideas of Valentin Volosinov, the Russian linguist – for whose work I still have a huge admiration. I suspect that my chapter on ‘A dialogical approach to ideology’ shows all the signs of having been a struggle to make sense of a really difficult book – but I think it still stands up. The key concept at the end of the struggle, is Volosinov’s concept of ‘little speech genres’: that is, located and historically specific modes of speaking and hearing that carry within them the results of all kinds of struggles to manage (bits of) the social world. I am sure that it would not be difficult to build links and connections to some of Antonio Gramsci’s works on the politics of culture. But Volosinov was the key, to me. ‘Power’ in ideology thus became not like ‘effects’ or ‘affordances’ or anything like that – it became a function of the operations of institutions which provide homes to ‘little speech genres’. Is that the same as Foucault’s notion of distributed discourses? I don’t think so – but I can see that the topic deserves debate.

Q: In From Antz to Titanic, you write that scholars who write about audiences without speaking to audiences end up ‘constructing figures of the audience’ through ‘imputation’. What do you mean by this?

I’m not alone in this. There is now a strong body of really good scholarship on what I have called ‘figures’, and what others have called ‘images’, or ‘myths’, or ‘presumptions’ of the audience. Perhaps my favourite book on this is one that is a bit weird, but hugely interesting: Edward Schiappa’s Beyond Representational Correctness (2008). Schiappa is a very ‘American’ (in the sense of the methods he uses) communications researcher, who examines the ways scholars of television in particular arrive at conclusions about the impact of shows on their audiences from forms of textual enquiry. He simply and insistently asks: can we check and see if these claims can be operationalized and tested? OK let’s mount a small experiment … And of course they don’t stand up. Still, who cares? Our fields are generally not that taken with the idea of ‘testing claims’.

But where Schiappa is particularly concerned with strands of academic thinking and practice, I am as much concerned with the role of claims about the audience in the general public arena. Some of these are so small and local as to matter not a whit: when a reviewer asks ‘what will the audience make of this?’, then s/he is not making strong claims about the unity and vulnerability of viewers. But the claims are often carried forward by more disturbing rhetorics, and by images (I have in my collection an illustration from the Daily Mail from the time of the video nasties campaign, showing a horned creature watching the TV screen, implying without saying that the ‘nasties’ are the work of the devil, with a headline screeching that children are being ‘taken over by something evil from the screen’ …). So I prefer the term ‘figure’ because it reaches more widely. It includes everything from those relatively benign use of the expression ‘the audience’ by reviewers, to highly condensed and charged claims about what must be happening as ‘they’ read/watch/listen to whatever ignites the fury of moral campaigners. Sometimes they construct semi-coherent ‘theories’ of how the ‘effects’ they fear are generated. Sometimes they work simply by denunciation. But it has long struck me as part of the responsibility of people in our (relatively privileged academic) situations, to try to draw out their claims, examine them in broad daylight, and bring expertise to bear on testing them. Sadly, too many who work in our fields are content just to contribute to their construction rather than their testing – nowhere more so, in my experience, than in people who work with ‘spectatorship theory’.

I happened to re-read the other day a short piece I wrote in Screen in 2002, about academic responses to David Cronenberg’s film Crash, which was the locus of one of my first big audience research projects (with two colleagues, Jane Arthurs and Ramaswami Harindranath). I talked about my (genuine, not put-on) astonishment that hardly one film academic spoke up in defence of the film, when it was attacked for over a year in the UK, the Daily Mail making all kinds of stupid claims about its ‘dangers’. Instead, Screen published a series of ‘analyses’ of the film which, when I looked at them, were built on a kind of up-side-down version of the Mail was claiming about the film. The Mail and its allies were scared that the film might ‘arouse’, or ‘heat up’ people’s interests in sex and cars. The academic analyses were all about the question of whether the film was ‘cool’, ‘distancing’ (because if it wasn’t, that was a ‘bad sign’). All in the name of ‘film theory’… I found – and still find – that kind of thing simply irresponsible.

Q: You have studied audiences for a considerable portion of your lengthy academic career. What have you learned about audiences? Why is it important in your mind to consider reception and audiences? Are there common themes and conventions that continue to emerge, patterns as well as divergences?

I dread this question. It is one I sometimes ask myself, and am never very happy with any answer I give myself. I fall back, in my mind, on a series of particulars (this audience here, that context there) – and to some extent that has to be right. Asking the question is risks being the equivalent of asking a chemist what he has learned in his career about ‘chemicals’ – to which the only answer could be ‘which ones, in what contexts, interactions’, etc?. One of the things that I have learnt as an audience researcher is the sheer power and complexity of context. People fashion their responses to cultural materials out of personal factors (their individual histories, ages, company, novelty, previous encounters, etc, etc – there are going to be a lot of those), physical situation (where and how they encounter the materials – from locality, architecture and scale, right up to warmth, hunger, need for the loo, etc, etc – here we go again), circulating attitudes and discourses that they butt up against (gossip, debates, reviews, etc, etc), larger configurations (assumed ways of doing things in their period, generation, friendship groups, etc, etc), and … add your own long list of etceteras. A big challenge for audience researchers, it seems to me, is never to lose sight of the operation of all these complex contexts, yet still to try, as honestly as we can, to identify patterns and tendencies, connections and structures.

There are however some recurrent outcomes of all the audience researches I have done. Perhaps most importantly is captured by the highly tricky word ‘engagement’. Liz Evans (from Nottingham University) is publishing a book on this in December 2019 (Understanding Engagement in Transmedia Culture). She argues, rightly, that we need to be cautious how we use this, since it has become a powerful marketing term/ambition (how to ‘engage’ consumers deeply). But she acknowledges that it is a term she is regularly tempted to use herself. I am, too. I am much taken with the rising interest, in various areas, in dense engagement with media. Fan studies is one branch of this, without question. But it appears elsewhere in various forms. I simply love Alf Gabrielsson’s Strong Responses to Music, which is based on the talk of devotees of many different kinds of music, and explores the ways people characterise how the music impacts on them. Some of these would no doubt be classable as ‘fans’, in the sense of engaging in multiple arenas with talk and materials about their beloved traditions, but some are essentially private. I recall too with affection an early book by an unusual neuroscientist who was fascinated by the way people become Lost In A Book (Victor Neil’s title for his 1988 study). What these and a range of other studies seem to me to show, is that the denser a person’s engagement with whatever cultural form is their choice, the more complicated, ‘slowed’, combinatory (sensory, cognitive, emotional, evaluative) their response is.

For the rest, the most important things I have learned about audiences is (a) their localised unpredictability – moving from one context to another, you rarely find the same things, and people also evolve their responses and views, (b) in the main, if they trust you, they are extraordinarily generous with their time and thoughts. A few years back I stumbled over one response in our database of completions of our Hobbit questionnaire. It was from a Syrian refugee, writing from Russia where she had fled the war, but writing about how the English language was so important to her as something beyond her war-torn country (and an abusive father as well). She talked at great length about the importance of Tolkien’s work in keeping her sense of possibilities for a better world alive. I wrote about her in an essay I published in a Finnish journal Fafnir, because she touched me greatly.

What I have just said, I have long realised leaves me in a tricky position. If audiences are so localised, and so mobile, can there be much in the way of a general theory of audiences and audiencing? I am genuinely unsure. While I work on that, or until I conk out, I will hopefully carry on with the work on Participations – which seems to me to exemplify that wonderful panorama of differences, localization and complexity that I am talking about !!!!

Martin Barker is Emeritus Professor at Aberystwyth University, and Visiting Professor at UWE Bristol. Following a career which began in 1969, he finally – with a small sigh of relief – retired from teaching in 2015, but is still doing research as he is able. Across his research life, he has studied (among other things) contemporary British racism, children’s comics, censorship campaigns, and a variety of particular films. But he has over the last twenty years particularly focused on the development of audience research in a cultural studies mode – including trialling and developing a mode of quali-quantitative research. He is founder and now Joint Editor of Participations, the online journal of audience and reception studies. His major audience projects include the international Lord of the Rings, Hobbit, and Game of Thrones projects, and he has led contracted research for the British Board of Film Classification on audience responses to screened sexual violence.