'Less is Moore: Alan Moore's 2000AD Short Stories,' Andrew Edwards (Part 2 of 2)

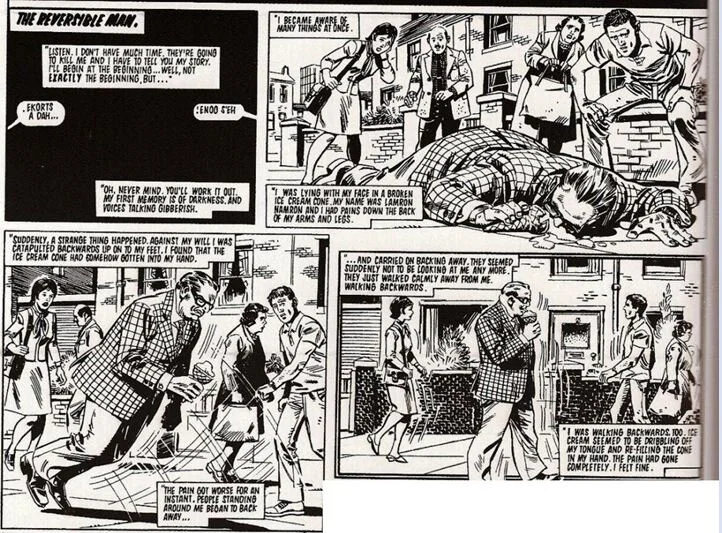

/This interest in time, allied to experimentation with the comics’ form, is also explored in ‘The Reversible Man’ (Prog 308, 19th March 1983). The depiction of backwards motion in a static medium like comics is achieved through manipulating what the reader reads and sees. Dialogue, from the very first panel, is reversed: ‘… had a stroke’ becomes ‘ekorts a dah’.

Furthermore, the order of the panels are arranged in reversed chronological order, which becomes apparent when you look at the just the visual content of the panels in reverse order, moving from the final panel on page four and ending with the first panel on page one. The caption boxes are set against both the backward motion of dialogue and visual panel arrangements. They allow Moore to narrate from the perspective of the protagonist who experiences his life in reverse, which anchors the meaning of the story so that it does not become too confusing an experience.

In addition to prefiguring the theme of time and formal experimentation in Moore’s later work, early consideration of the nature of superhero comics is also evident. With artist Bryan Talbot, he provides a comedic meditation on the nature of supervillains in ‘The Wages of Sin!’ (Prog 257, 27th March 1982) by asking what an unemployment training scheme for supervillians would be like. Here Moore draws upon a social issue that was prevalent at the time, combining it with supervillain conventions for comedic effect. One such convention is the notion of ‘taking candy from a baby’, which is literally manifested here. Humour is engendered when one student proves incapable of performing this act.

In addition, a student is rebuked by the teacher, Mr Dreadspawn, for suggesting that a hero can be dealt with by shooting him:

Give me strength! How’s he going to escape and defeat you if you shoot him?

This subversion of this narrative code both is both humorous in drawing out the absurdity of the statement and acts as a critique of an overused narrative convention. Furthermore, the creation of a supervillain identity through changes in name (Anthrax Ghoulshadow) and appearance are also portrayed, along with other conventions relating to dramatic poses and story conventions:

Such conventions also include a specific stereotypical appearance, that of the villain being bald, either with or without a metallic prosthetic limb. Ghoulshadow’s appearance recalls examples that include Ming the Merciless (Flash Gordon), Lex Luthor (Superman), Dr Sivana (Captain Marvel), and Ernst Stavros Blofeld (James Bond); for prosthetics, we can count Herman Scobie (Charade), and the fisherman (I Know What You Did Last Summer); for both baldness and prosthetics, Captain Hook (who wears a wig in Peter Pan) and Freddy Krueger (The Nightmare on Elm Street series) are key examples.

Another particularly noteworthy story is The Regrettable Ruse of Rocket Redglare (Prog 234, 17th October 1981). It opens with an exhortation to readers to remember previous stories, albeit ones that have never actual existed: this recalls the ‘unavailable story’ idea evident in Marvelman and Captain Britain. The use of alliteration also alludes to Stan Lee's characteristic usage, when Rocket Redglare is described as being the ‘sentinel of the spaceways and enemy of evil extra-terrestrials.’

In ‘Rocket’ the standard hero versus villain fight is subverted by making it a staged exercise in public relations. Rocket Redglare is an older superhero who is having image and financial problems, portrayed here for comedic effect: he is an overweight superhero who has to wear a corset to fit into his costume:

He arranges to stage an invasion with his own nemesis, Lumis Logar, in order to boost his popularity and earn more money. However, the villain takes the opportunity to take his final revenge in a twist ending, and Redglare is killed, which confounds reader expectations that the hero should win. Furthermore, Moore’s interest in the aging superhero is at odds with a genre where characters never age in order to remain commercially viable, and prefigures his more profound dealing with this theme on Marvelman and Watchmen.

The expectation of where a story will go, an expectation built upon previous stories' developments that have become predictable (or stereotypical), is a concern of narratology. Scholars such as Vladimir Propp and Joseph Campbell showed how plot progression can conform to established patterns. Moore uses these patterns and subverts expectations for comedic effect here. By having the hero work with the villain, and having the villain triumph at the end of the story, Moore is drawing on wider archetypal story structures, and this is a kind of intertextuality in itself. As such, there appears to be levels of intertextuality at work: Rocket Redglare is, on one level, a Flash Gordon pastiche: moving the frame of reference outward to the next 'broader' level he is a spaceman hero who is written within recognisable generic conventions, albeit subverted ones; finally, at a broader level upwards again he is a 'hero' in the Proppian and Campbellian sense. Subverting an expectation on one level (e.g. the 'Flash Gordon' level) also leads to subverting the wider levels ('spaceman hero' and 'hero'), in turn subverting specifically the narrative expectations implicit in the Proppian and Campbellian models.

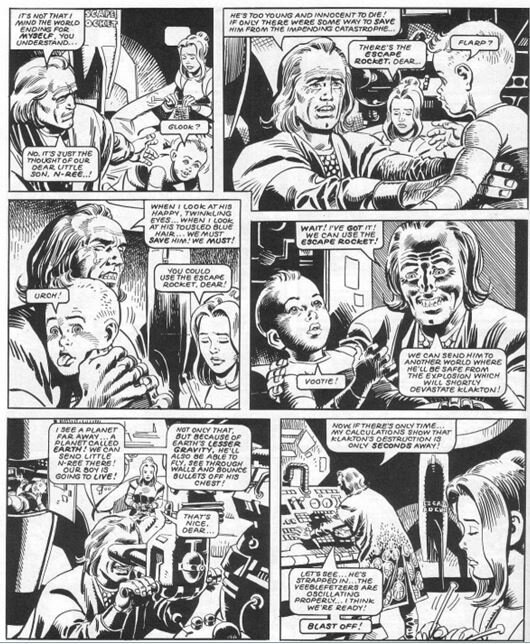

Another manifestation of such subversion is found in ‘Bad Timing’ (Prog 291, 20th November, 1982), which subverts the origin story of Superman. Its intertextual relationship with the precursor text is mandatory for understanding the full scope of what Moore is trying to achieve. The story begins in 1938, which is the first subtle indication of the relationship with the Superman character that is being forged here: his first appearance occurred in Action Comics #1 (June 1938). The story works on the concept of a doomed planet and a scientist who sends his infant son to Earth.

A short summary of Moore’s changes will illustrate how indebted this piece is to Superman’s origin story: Krypton becomes Klackton; Superman’s parents Jor-El and Lara are transformed into R-Thur and L-Sie; Superman’s Kryptonian name Kal-L becomes N-Ree. The names Moore gives to his character are based on more familiar names (Arthur, Elsie and Henry respectively), and the name of the planet is probably based on the British resort town of Clacton-on-Sea. Also, a reader will not even need to have read the original version in Action Comics #1 (or a reprint): they may have read a recounting of the events from any number of subsequent Superman comics, seen the 1978 film, or know of the origin from a third party: the story has passed into the wider culture through the propagation of memes like ‘Krypton’ and ‘Clark Kent’, which are recognisable to people all over the world.

Moore’s twist on this is having the planet not explode, and for the infant’s craft to inadvertently signal a nuclear war in 1983. ‘Bad Timing’ was published on 20th November, 1982, predating the year that the alien craft nears Earth, 1983, only by a small margin. In the 1980s the threat of nuclear armageddon was an important topic, and Moore taps into the resulting anxiety it caused by showing its effects as occurring in the then very near future. The presence of nuclear anxiety also foreshadows its use in V for Vendetta and Watchmen.

Such foreshadowing underscores the assertion made above that these stories prefigure the later, major works in Moore’s oeuvre. In this, the value of these early stories in assessing the development of Moore’s skills, the thematic and formal development of his work, and the trajectory of his whole career should not remain underestimated.

Andrew Edwards is a comics scholar and writer. His research interests include comics and graphic novels, science fiction, horror, intertextuality, and representations of gender. He gained his PhD in intertextuality and gender in the work of Alan Moore in 2018 at Wrexham Glyndwr University, where he also works as an Academic Skills Tutor. He is currently writing a book about Moore, Bissette, Totleben and Veitch’s Swamp Thing for Sequart. He can be followed on Twitter: @AndrewEdwards88